Thirty-five years after World War III, also known as the Water War, all life forms have been destroyed by the adverse effects of climate change, and Earth is now as barren as a desert. Sheltered from the environmental degradation, however, is a self-contained, high-tech, underground community called Maitu, where memories are actively suppressed, condemning members eternally to a dystopian present. Each citizen of Maitu is allotted a small amount of water each day, so urine and sweat are recycled and stored in a personal water can. When Asha, a young museum curator, starts to dream about a verdant tree growing in the desert, she is forced to take dream-suppressant pills.

One day, Asha receives a mysterious package from outside Maitu, bearing a soil sample filled with moisture and containing no radioactive matter. Against the orders of her community rulers, she secretly cultivates a seed in the soil sample, which grows into a budding plant. A daunting quest ensues for Asha, as she tracks the source of the life-bearing soil and explores the world outside Maitu.

Asha is the Black female protagonist of the short Kenyan science-fiction film “Pumzi,” a word that translates as “breath” in Swahili. Directed by Wanuri Kahiu and released in 2009, it is part of an emerging genre, dubbed “Africanfuturism” by the Nigerian-American writer Nnedi Okorafor, which blends sci-fi elements with creative visions of the African continent and its future, people and civilizations. Africanfuturism is a subgenre differentiated from Afrofuturism in that it is led primarily by African artists and envisions alternative futures for Africa and Blackness beyond the imagination of the Black diaspora.

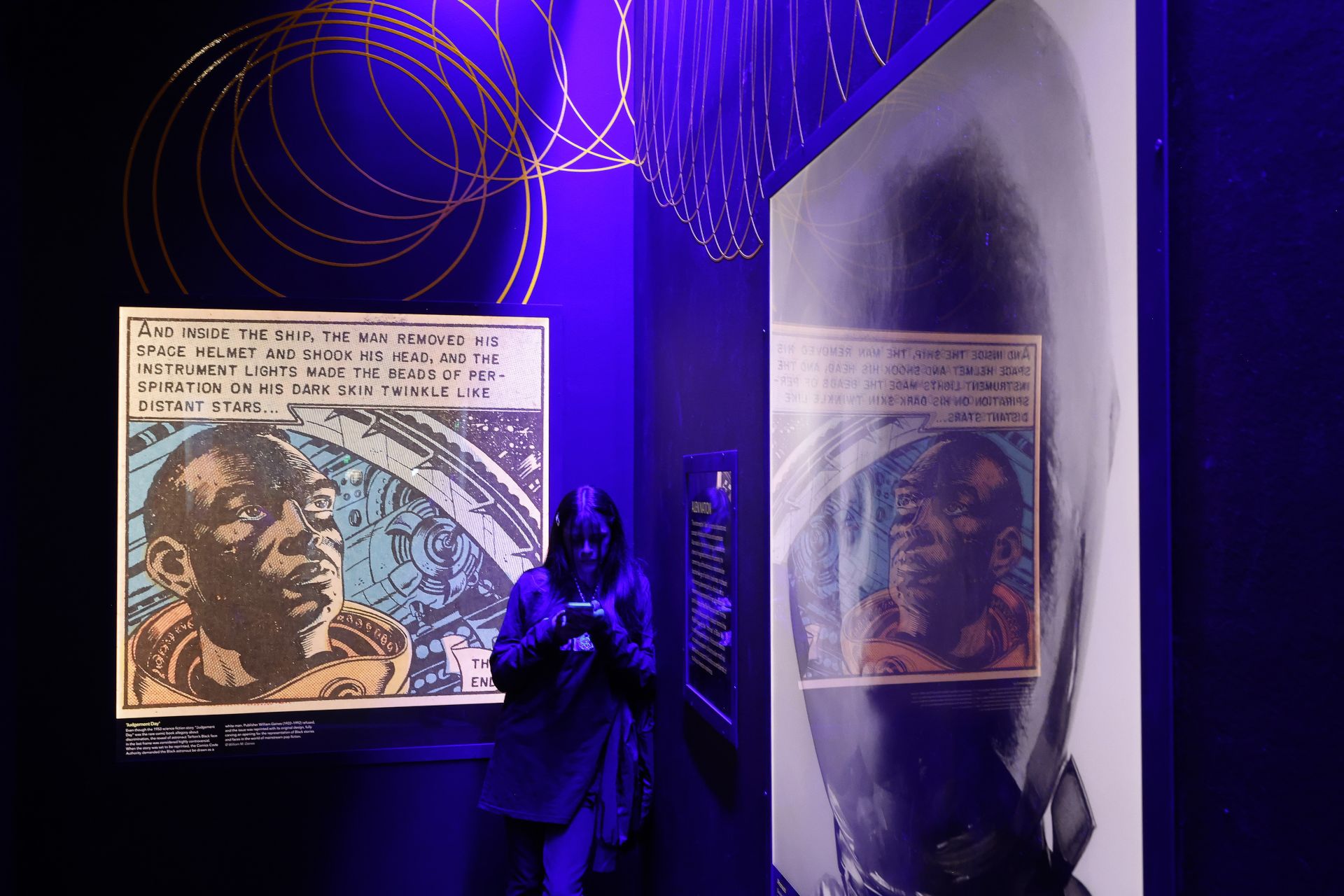

In a 1994 essay titled “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel Delany, Greg Tate and Tricia Rose,” the American cultural critic Mark Dery bemoaned the low volume of science-fiction literature produced by Black writers. Except for works by eminent African-American writers such as Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany, much of the genre featured protagonists who were just as white and masculine as their authors. As Dery observed, the social conditions of Blacks resonated with the lowly ranking of speculative fiction in Western literature. A genre comprising science fiction, horror and fantasy, speculative fiction didn’t count as serious literature for the American literary elite and was largely restricted to pulp magazines. For instance, Frank Herbert’s “Dune,” recently adapted into a blockbuster Hollywood screenplay, faced 23 rejections from publishers.

Coining the word “Afrofuturism,” Dery envisioned a form of speculative fiction that addressed racism, political alienation and other such issues felt deeply in the African-American experience, merging the aesthetics of science fiction and forms of 20th-century techno-culture to imagine empowering possibilities for Black people. Dery’s concerns appeared to echo the grand prophetic vision for the Black diaspora held by African-American jazz artists such as Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock and Sun Ra — who starred in “Space is the Place,” a 1974 science-fiction film that depicts an interstellar trip to Earth to rescue the Black race from an evil overseer and an exploding planet.

By inviting African-descended people to question preconceived notions of Blackness, Afrofuturism rebuked the defeatist mindset of “Afropessimism,” a notion that gained currency in Africa during the 1980s. More than 20 years after many African nations obtained independence from their European imperial masters, a creeping sense of despair gripped the continent as new troubles surfaced. The new dispensation of postcolonial leadership — dominated by military dictatorships — botched the exploitation of Africa’s natural resources and drove much of the continent to ruin. In the wake of its economic crises, an otherwise resource-rich continent turned to foreign aid and debt to stay afloat. One aspect of this aid could be seen in the structural adjustment programs imposed by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund on a number of African economies.

These brought no succor to the long-suffering masses. The World Bank’s conditions for the economic adjustment policies compelled the debt-ridden governments to retrench, cutting spending and public employment. These measures conspired with problems of corruption, political instability and disease, among others, to reduce the standard of living for many Africans. As such, outside observers considered Africa to be self-destructing, expressing a prevalent skepticism about the possibility of sustainable progress, peace and development for the continent. Negative portrayals in Western mass media would seal these doom-laden assumptions, as exemplified by the May 2000 weekly bulletin of The Economist, which featured a map of Africa and the headline, “The Hopeless Continent.” Reinforcing these bleak outlooks about Africa were popular motion pictures such as “Blood Diamond,” the Leonardo DiCaprio thriller that drew on the deadly consequences of illicit diamond trading in Sierra Leone; “Hotel Rwanda,” with its simplistic portrayal of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide; and even the 2009 South African science-fiction film “District 9,” which alludes to the country’s history of apartheid.

Afrofuturism emerged as a cultural movement to counter these grim assumptions about Africa in mainstream media and project ambitious representations of a future for the continent powered by technology, shorn of Western influence and isolated from the trauma of past oppression.

This Afrocentric creed would inspire the 2018 film adaptation of the Marvel superhero comic “Black Panther,” which signaled a mainstream breakthrough for the movement. With a predominantly Black cast and crew, “Black Panther” projected a technologically advanced and culturally rich continent, devoid of Western dominance, which was in part a retort to the white supremacy of the Donald Trump era. More Afrofuturist films burst into the mainstream within the same year, often to wide receptions. The Oscar-winning “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse,” in which a Black kid from Brooklyn becomes Spider-Man, provided a stark contrast to earlier iterations of the franchise. Then there was Jay-Z and Beyonce’s music video for “Family Feud,” set in the year 2444 and pointing to an ideal future America governed by women. “Black Panther’s” release ultimately buoyed interest in African culture, particularly among contemporary African-American artists like Kendrick Lamar and Janelle Monae, whose pop music weaves utopian imagery with elements of space travel.

For all its acclaim, though, Afrofuturism was perceived among native Africans as primarily catering to the diasporic concerns of African Americans. The prefix “afro” referred to the 20th-century techno-culture and pop culture of African Americans — and not necessarily to Africans. Starting in late 2019, some African writers of speculative fiction began to distance their work from the term Afrofuturism, which they regarded as a misnomer. They pushed for a more specific label that acknowledged African cultures and the nuanced experiences of its natives. Foremost among this group was the Nigerian-American writer Nnedi Okorafor.

Writing on her personal blog in October 2019, Okorafor coined the words “Africanfuturism” and “Africanjujuism” as subgenres of science fiction and fantasy, respectively, that fused “true existing African spiritualities and cosmologies with the imaginative.” While acknowledging that Africanfuturism is similar to Afrofuturism in the way that Africans on the continent are bonded by ancestry to those in the diaspora, Okorafor maintains that the former is embedded in African mythology and history and does not prioritize the West as does the latter. In Okorafor’s view, Wakanda — the nation-state at the core of the Black Panther series — should have sited its first colonial outpost within an African country rather than in downtown Oakland, as depicted in “Black Panther.” Given that its central default is African, Africanfuturism need not transcend the continent of Africa nor speculate about technologies or futures that span other worlds, as is common with Western-oriented science fiction.

Okorafor’s fiction infuses elements of magical realism and fantasy that are inspired by her Igbo ancestry and other African mythologies and spiritualities. Her characters might speak Igbo or Yoruba (both West African languages) or confront problems that are peculiar to the continent, giving her fiction a distinct African flavor. While employing technologies that pay homage to African legacies, such as “nsibidi,” a West African system of writing that dates as far back as the 15th century, Okorafor rebukes the claim that scientific knowledge and technology are the exclusive domain of the West.

In a TED talk delivered in 2017, Okorafor wondered, “What if an African girl from a traditional family in a part of future Africa is accepted into the finest university in the galaxy, planets away?”

The answer to this would appear in her “Binti” trilogy, which follows a 16-year-old female mathematics genius (identified as Binti) who is admitted into an intergalactic university on another planet and becomes the first person from her community to attend a university beyond Earth. Binti hails from the minority Himba tribe in Namibia. Her compatriots, the Khoush tribe, wield authority over the other inhabitants of Earth. During her interstellar journey, an alien species known as the Medusae attack her spaceship, killing every student aboard except Binti. Her later struggles with belonging and identity in an unfamiliar universe are made to reflect the struggles of Africans navigating a globalized world.

Unlike Afrofuturism, Africanfuturism is not simply the presence of Black bodies in technologically advanced spaces. For Africanfuturists, ancestral locations and spiritualities are as significant as the technology-powered futures they conjure, pushing “the characters [to] serve as the primary cultural mediators of their own destiny,” said Patrycja Koziel, an academic at the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences. In “Children of Blood and Bone” (2018), the author Tomi Adeyemi tells the story of a world steeped in Yoruba culture and mythology. The book, which is part of a trilogy, follows the fictional Orisha kingdom, where a ruthless dictator has banished all historical magic traditions. Zelie, a member of the oppressed class, is determined to restore the magic and liberate her people, but she must wrestle against betrayal and forbidden love. Adeyemi weaves heavy influences from her native Yoruba culture into the fabric of the story, as seen in names like “Orisha” and “Egungun,” which reference Yoruba deities and spirits.

Yet Africanfuturism had been a steady undercurrent in African literature long before Okorafor’s proposal. The works of writers like Ben Okri and Buchi Emecheta embodied this ideal. Okorafor would even cite the latter as a great influence on her own oeuvre. In “The Rape of Shavi,” Emecheta conjures an idyllic African utopia known as Shavi, which changes for the worse when a band of Europeans fleeing the imminent nuclear destruction of the Western world stumble upon it. Set in 1983, the novel’s probing of the nuclear anxiety of the 1980s and the European conquest of Africa aligns with dystopian science fiction.

Africanfuturism may be interpreted as a globally transportable category of identity connected to the history of the continent, its vibrant spirituality and its vivid materialism. This idea was visibly represented in a collection of eight stories by authors from Nigeria and Zimbabwe titled “Africanfuturism: An Anthology.” Published in 2020, the collection heralded a new Afrocentric movement that identified more with the intricate structure of the African continent than did the well-established Afrofuturism. In these stories, the protagonists might be based in extraterrestrial or high-tech, futuristic locations, wield extraordinary powers to wrestle against a postapocalyptic world, or remain torn between different realities while steeped in Indigenous and social knowledge.

In recent years, this cultural aesthetic has spread from book pages onto the silver screen. A new wave of films from the continent has brought Africanfuturism into the limelight. Nowhere is this more prominent than in the 2023 fantasy thriller “Mami Wata,” by the Nigerian director C. J. Obasi, which draws heavily on the rich folklore of West Africa. The film takes its title from the fabled West African mermaid deity notorious for her seductive beauty and supernatural power. This mermaid deity serves as the revered village goddess in Iyi, an idyllic seaside village untainted by civilization, until her power is challenged when a young boy dies from an avoidable disease. “Mami Wata” probes the conflict between African traditions (represented by a village priest) and Western ideologies (symbolized by a crucifix-wearing rebel). The black-and-white film combines African tropes such as white facial markings and West African pidgin English to resonate with its African roots and emphasize the beauty of black skin.

“Mami Wata was born from a need to see a new kind of African cinema … that draws on age-old storytelling, myths, fables, mysticism and even feelings conjured through time,” Obasi told New Lines.

Generally, Obasi’s films plumb the depths of African mythologies using a fresh perspective that evokes a sense of nostalgia. “The vision might be new, but the idea and the feeling transcend time,” he added.

After it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2023, “Mami Wata” was submitted as Nigeria’s entry for the 2024 Academy Awards.

If Africanfuturism shifts the gaze from the diaspora to the continent, it also centers the history of Black women, whose bold advocacy for political recognition has been erased by stereotypes of victimhood and passivity. Indeed, Okorafor’s use of female protagonists mirrors the history of female leadership — and also the culture of inequality — in many traditional African societies. In the trilogy, Binti confronts gender and racial discrimination within her world and outside, challenging society’s stereotypes and carving her own path.

The same feminist ideals are to be found in Kahiu’s “Pumzi,” which hints at the ecological crisis of droughts and water shortages in East Africa, issues that persist in the region. Asha’s defiance of the orders of the Maitu council elders, and her quest to explore the desolate landscape of the outside world in search of her dreams, emphasize the power of Black women to take control of their destinies. Sacrificing her labor, and ultimately her life, Asha nurtures the plant with sweat collected from her dying body. Eventually, the plant blossoms into the luxuriant tree in her dreams, restoring vegetation to a desolate earth. Beyond its concerns around climate change, “Pumzi” depicts the African woman as an integral life force indispensable to the survival of the global world.

“Africanfuturism is a space for strong feminist representations and manifestations of ideas … related to gender inequality, violence against women and sexuality,” Koziel said, adding, “By creating the future, women gain space to express themselves, regaining control over their own narratives.”

While African literature has seen an upsurge in speculative fiction, the result in its cinema has been far less apparent. Western films like “Black Panther” have met with rousing enthusiasm in Africa, as in its diaspora, yet African films with speculative themes have not gleaned as much excitement. Despite its surging theatrical run on the foreign scene, “Mami Wata” has met with a lukewarm reception from its domestic audience, a problem Obasi attributes to Nigerian film distribution.

Yet part of this problem may lie with Africanfuturist films, which tend to be short. “There isn’t enough to categorically say that there’s a wave of [speculative fiction], but we’ve seen small attempts,” said Jerry Chiemeke, a writer and culture critic.

Compared to the growing body of speculative fiction in literature, there is but a thin vein of similar films, “because a lot of [African] filmmakers are still trying to figure out the market and trying to play safe,” Chiemeke explained.

Nonetheless, the launch of films like “Pumzi” and, more recently, “Mami Wata” unlocks a new degree of storytelling in African cinema — one not exclusively given to high-tech trappings but defined by varied mythologies and untainted by the dystopian visions of the rest of the world.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.