Successful resistance movements against autocratic regimes require collective people power. They are also increasingly becoming long shots, as 21st-century authoritarian states grow more adept at throttling dissent, often using new surveillance tools the East German Stasi could have only dreamed of possessing. From Russia to Venezuela to Myanmar, mass demonstrations in recent years have failed to topple dictators, while activists have either had to flee, face imprisonment or die. Global freedom — political rights and civil liberties as measured against the Universal Declaration of Human Rights — has declined for the 18th consecutive year, according to Freedom House, affecting one-fifth of the world’s population.

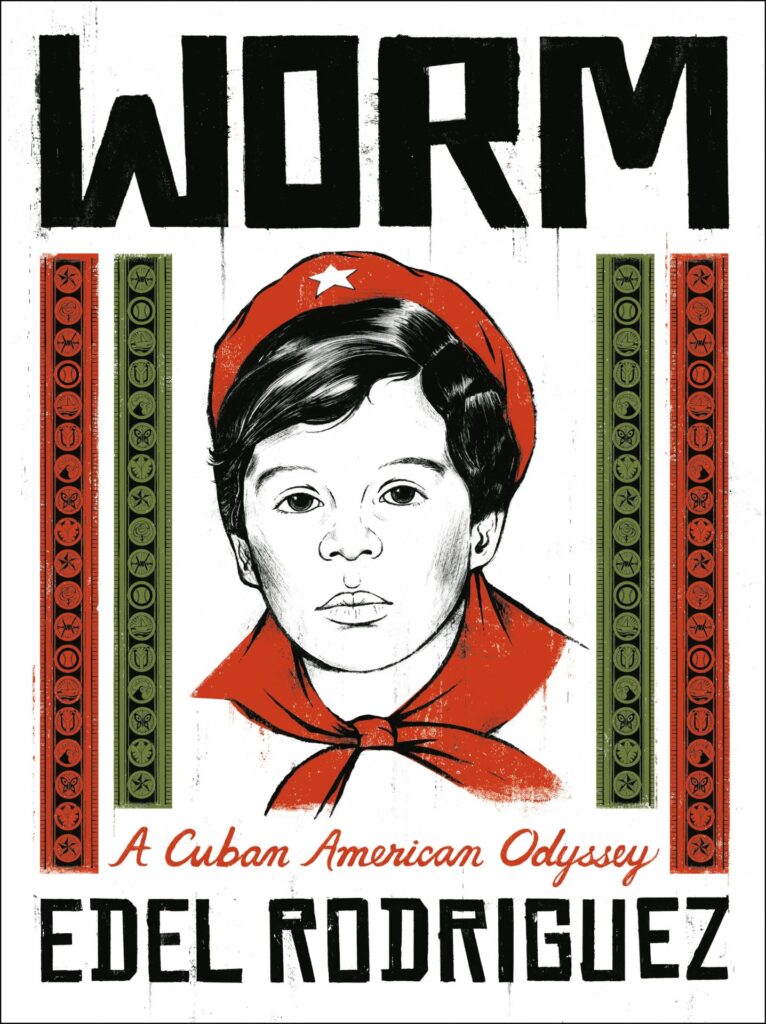

Two books in a genre growing in popularity around the world, and particularly in the United States, serve as antidotes to the authoritarian surge. “Woman, Life, Freedom” is a nonfiction graphic work examining contemporary Iran’s struggle for liberty, dignity and human rights. Centered on the wave of activism following the 2022 death of Mahsa Amini while in police custody for allegedly not wearing her hijab correctly, a collective of artists, journalists and scholars — led by Marjane Satrapi — tells the story of the recent nationwide protests, which represent the biggest threat to the Islamic Republic since its establishment in 1979. In “Worm: A Cuban American Odyssey,” artist Edel Rodriguez reflects on his personal journey fleeing Fidel Castro’s regime. His story of grit and eventual success in the U.S. — only to witness the emergence of a new threat to the republic with the election of Donald Trump — is a cautionary tale warning us that potential despots are present in all political systems.

“Woman, Life, Freedom” is Satrapi’s first nonfiction comics project since the global success of “Persepolis,” a memoir that covered her life before and after the Islamic Revolution, including her eventual departure to Europe. The book introduced millions of readers to the tyranny of the regime, becoming one of the most influential works in the genre in a generation and helping to introduce visual storytelling to new audiences. Moving a global audience, however, had little bearing on circumstances on the ground. Successive rounds of protests have failed to bring down the government — nor have they offered Iranians even incremental wins, despite growing discontent. Each season of protest has been met with a heavier iron fist of mass arrests and executions.

“Woman, Life, Freedom” is divided into three parts. The first section serves as an explainer for anyone unfamiliar with the 2022 protests. The second covers the history and context in which they happened. And the third takes a closer look at the many brave people who have fought back, from high-profile dissidents to nameless citizens across all ages, social classes and ethnicities.

It is not lost on Satrapi that little has changed in Iran between the publication of her first and second graphic works. The futile years become a Sisyphean blur, but one of the work’s central arguments is that this time it is different. In some closing thoughts, Satrapi is defiant and confident that “Iran’s destiny will ultimately be one of freedom.”

The graphic novel format plays a special role in our age of short attention spans. In the Instagram era and after two decades of the multibillion-dollar Marvel franchise, the genre is seeing growing numbers of readers among children and adults alike. Globalization, particularly American exposure to Japanese manga and European long-form comics, has also changed tastes.

While compelling contemporary political tracts have made bestseller lists, the urgency of the moment demands creative ways to reach as wide and as mainstream an audience as possible. New York-based Rodriguez, for example, leaned into this following the rise of Trump. The illustrator is likely best known for his stinging and provocative political art. His flaming orange depictions of the former U.S. president as a terrorist cutting off the Statue of Liberty’s head or wearing a Ku Klux Klan hood went viral on social media and also appeared on the covers of Time and Der Spiegel magazines. That he would apply his talent to producing sequential art with a political bent is a natural progression of that ethos. Having spent most of his childhood in Cuba, Rodriguez knows an authoritarian threat when he sees one.

“To an immigrant like me,” he writes in “Worm,” “America is a dream, a land of freedom and opportunity where one can work and express oneself without fear of violence or political persecution. For me, January 6, 2021, shattered the dream,” referring to the date on which Trump supporters violently stormed the Capitol in an attempt to interfere with the congressional certification of Joe Biden as president.

Rodriguez’s work therefore tackles authoritarianism on two fronts: the present, far-right threat facing the U.S. and his experience with the Cuban regime.

Comics — a medium where superheroes wrestle with villains in cosmic fights between good and evil — feel particularly well suited to explain our parallel, real-world face-offs. Satrapi and Rodriguez’s books stand on the shoulders of works such as Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust memoir “Maus,” the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize, in 1992. Its success spurred a round of political nonfiction releases in the genre, but this was the 1990s — democracy had won the Cold War. It was the “end of history” and the threat of authoritarianism felt far away. In 2024, we are less sanguine, and Satrapi and Rodriguez’s graphic novels are part of a new wave of books in which art and activism meet.

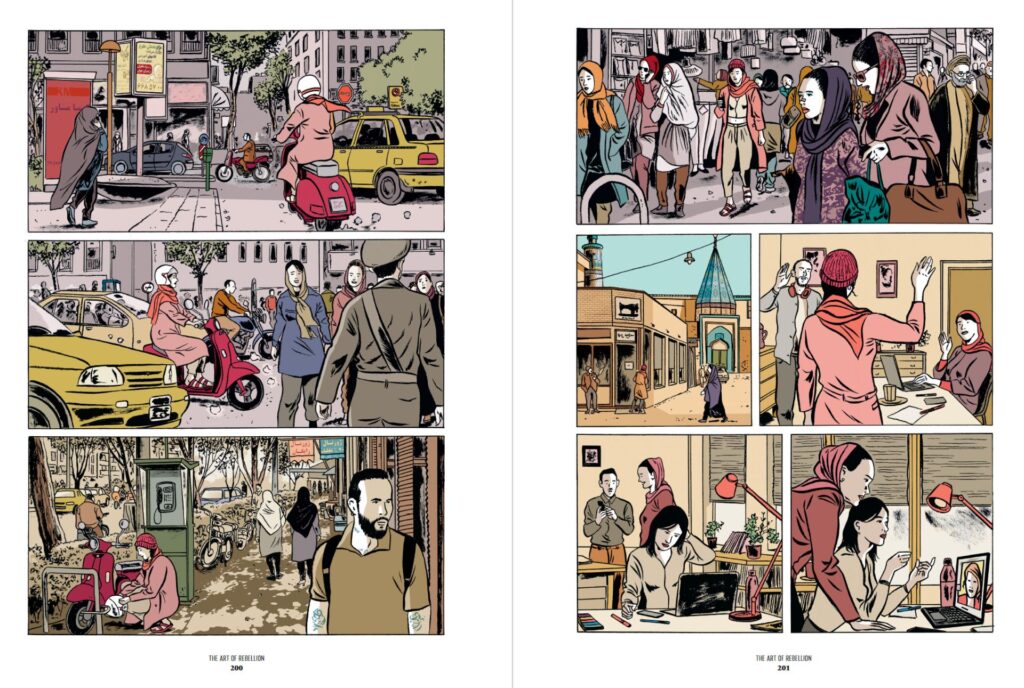

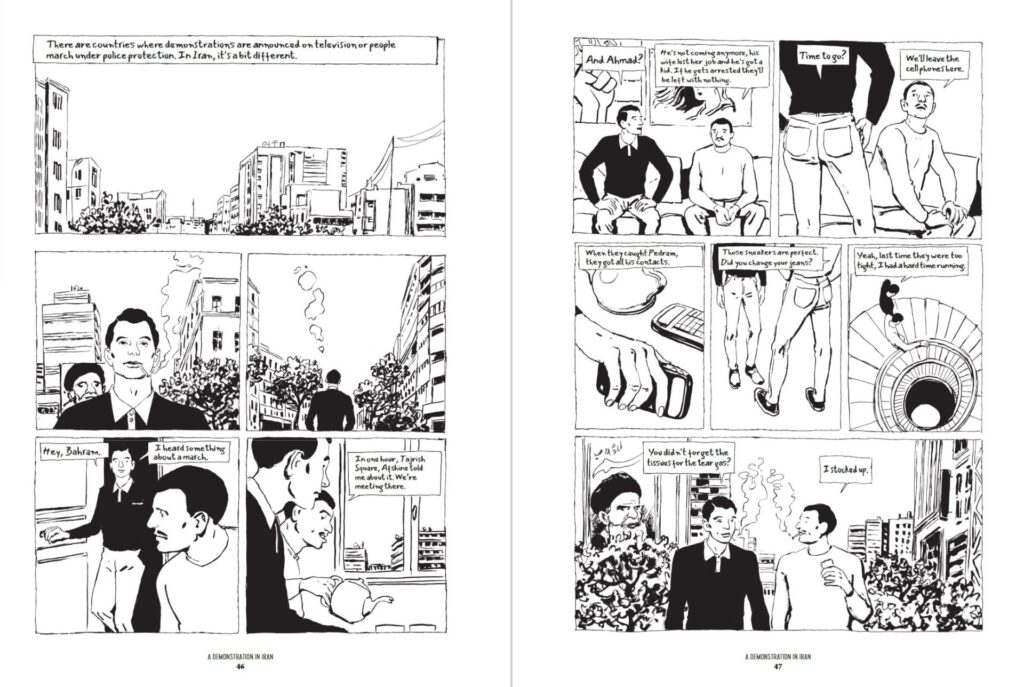

In “Woman, Life, Freedom,” various authors and illustrators write and draw the series of vignettes, stories and essays, producing different graphic moods. Iranian-Canadian artist Shabnam Adiban presents the lyrics of the de facto protest anthem with colorful, tween-friendly art. The next chapter pivots to French artist Pascal Rabate’s retro black-and-white renderings of a single day of protest, as scripted by Jean-Pierre Perrin, a former war correspondent for Liberation. That is followed by Mana Neyestani and Farid Vahi’s dark story of life in Iran’s infamous Evin Prison, where political prisoners are held. The overall result could have felt disorderly, but “Woman, Life, Freedom” is a beautiful compendium that underscores the importance of solidarity and community.

In one entry, a conversation over wine and cigarettes among Satrapi’s friends is sketched out. Interlocutor Abbas Malekzadeh Milani, a former Iranian political prisoner and now a scholar in the U.S., notes the undercurrents affecting the views of the majority. He is convinced that the collective psyche has changed and that this recent round of feminist activism, more than anything, has reshaped the resistance.

“This regime relies on three principles: men, resentment and submission,” he says. “But the new paradigm is: women, joy and fuck you!”

Iranians have come to fully appreciate how women’s rights are human rights, something Satrapi bemoans has taken men “too damn long” to fully appreciate.

Gen Z understands this best, sometimes at great cost. In a chapter titled “Names That Will Go Down in History,” readers learn about a series of youths, from Nika Shakarami, who burned her veil at one of the protests and is later killed by security forces, to hip-hop artist Toomaj Salehi, whose video, made right before his arrest, calls for constructing “a beautiful world in our lifetimes, [to] live beautiful lives, men and women alike, all of us together.”

That may be the new spirit, but in the meantime — and as “Woman, Life, Freedom” also so painfully recounts — the country’s morality police continue with their macabre marauding on the streets, harassing Iranians with impunity over the smallest infractions, from wearing leggings or an unconventional jacket to singing.

Paris-based Satrapi largely corralled the talent of the Iranian diaspora, in part because it is far too dangerous for creatives inside Iran to contribute to her book or one like it. The relative absence of in-country participation underscores how these types of regimes, with their claims of nationalism and love of country, actually engender the opposite — they crush the best and brightest of their people, forcing them to flee into exile or submit, reducing their civilizations to a bleak mediocrity.

Rodriguez’s story of Cuba underscores this irony. Like Satrapi, he is someone who also fled his home and the tyranny that permeated it. Havana bears little resemblance to Tehran, either culturally or in terms of geopolitical importance. While Iran has stayed relevant and enmeshed in great power struggles, Cuba’s international moment happened in 1962 during the 13-day Cold War standoff known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Since the fall of the Soviet Union some 30 years ago and the loss of Moscow’s patronage, the Caribbean island has mostly become a global afterthought, rarely caught up in international proxy conflicts. But the universal truths of autocracies, and their variations on the themes of suppression and surveillance, produce familiar results for the people who live under them.

Where “Woman, Life, Freedom” contains multitudes, “Worm” is a solo project and unfolds in a linear narrative form. And where Satrapi made clear that Iranian disillusionment cut across all social classes, it primarily told the story of protest and struggle through the eyes of educated, middle-class protagonists. Rodriguez’s graphic novel centers on his youth in a comparatively poor family. The rural lens imparts a different flavor, one of kerosene-lit cabins and buckets to collect rainwater for baths. He chooses an army-green and rust-colored palette for his pages. The scenes, with farmers in dusty fields cutting down plantains with machetes, remind me how much Cuba, like Iran, has been frozen in time due to decades of state control of the economy and lack of innovation. I witnessed similar farmers wielding the same tools that Rodriguez depicts on my most recent reporting trip to Cuba just a few years ago: Agriculture and industry have failed to keep pace with the modern machinery of the contemporary global economy; low productivity leads to a spiral of poverty.

Living in a closed and controlled society brings out the best and worst in people. Snitches and betrayers lurk on neighborhood blocks, and misplaced trust in a loved one or a childhood friend can mean anything from social ostracization to imprisonment. This is the case in “Woman, Life, Freedom,” where conversations never feel relaxed unless they take place in whispers, behind closed doors — and this precariousness is also felt in “Worm,” as Rodriguez recounts his early years in a farming town outside the capital. The landscapes he draws manage to be both idyllic and tense. For some time, his father throws himself into playing the part of a socialist fanatic — much like my own father did as a red-scarfed Young Pioneer trapped in Communist China. My dad did not believe a word of what he sang or recited. Later, as a teen, he served as a model youth, a top student ready to serve Red China — until he bailed for Hong Kong. It is something my family understands. At some point, the pretense simply becomes unsustainable.

In Rodriguez’s telling, his parents find each passing year a greater trial. They also start worrying that their own children might slip away from them.

“They were being raised by the revolution, by [Fidel] Castro’s decisions about what was good for them, not by what their families wanted for their children. My parents felt helpless, trapped, like doors were closing on them,” Rodriguez explains.

His father begins to plan an escape. The family transforms into the title of the work, “worms” — Castro’s pejorative term for Cubans who seek to leave.

Over 2 million Cubans live abroad, while the country itself is home to only 11 million people. The diaspora is an indictment of the failures of the Cuban state to provide freedom and prosperity to its citizens. Similar figures tell Iran’s story. According to “Woman, Life, Freedom,” 8 million Iranians have left — “the greatest brain drain in Iranian history.” Young people desire promising futures, and parents whose own dreams have been deferred will go to great lengths to ensure their children have the opportunities they missed.

The most dramatic part of “Worm” is Rodriguez’s retelling of his family’s exodus during the 1980 Mariel boatlift. Cubans flailed for days — starving, thirsting and melting under the sun as they waited on the shores for deliverance. Rodriguez remembers how Cuban officers, intent on humiliation, strip-searched his mother in front of him.

“They were looking for gold, jewelry, money or hidden letters,” he recounts. “We were allowed to leave the country with only the clothes on our backs, nothing else.”

It is a harrowing tale of escape executed beautifully, each panel worthy as an independent work of art ready for framing.

Years later, when Rodriguez returns to Cuba for a visit in the early 1990s, he is confronted with just how critical his departure was when he sees the stark bifurcation between those who were left behind and those who had the chance to go. One childhood friend cuts sugarcane for less than $2 a week. Rodriguez realizes that he would never have become an internationally renowned artist had he stayed.

Satrapi, too, would have faced headwinds in Iran and likely could not have become the feminist artist and filmmaker she is. And neither Rodriguez’s nor Satrapi’s books could possibly be sold in Cuba or Iran. The two end up mediating their countries’ truths externally. Yet with each passing year, exiles inevitably lose some grasp of their homeland’s domestic zeitgeist. Overseas communities also struggle with the trauma of their departures, and in the worst cases — as highlighted by Satrapi — they must deal with mutual distrust and suspicion, uncertain about authoritarian reach via proxies and informants, even on democratic soil.

In that sense, immigrants who come from authoritarian states share a far more common experience than the majority of citizens in their new countries often understand. Not much needs explanation when an Iranian meets a Cuban, or a Chinese meets a Russian, about life back home. The governments are different and yet the same.

Immigrants are also acutely aware of threats to their respective democracies. Rodriguez makes it a pillar of his story, but the France that Satrapi lives in also faces a viable far-right takeover in its next election, with a 2027 victory for Russia-friendly Marine Le Pen looking increasingly plausible. After decades on the defensive, global authoritarianism is tightening its grip on already-closed societies and acting as an agent of chaos in democratic ones.

Will citizens be ready to suit up like Superman or Batman — or, more accurately, like Iranian youths such as Nika Shakarami and Toomaj Salehi — when the time comes? Heartfelt graphic works like Satrapi’s and Rodriguez’s look back at recent events, but they also imply forward action and activism. Readers are being asked to join the fight. Their books lay out the stakes and call on us not to stand on the sidelines as we collectively face an uncertain future.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.