On June 22, 1992, about two months after war erupted in Bosnia, a group of Serb paramilitaries arrested 15 Muslim men and executed them on a bridge in Foča, a small town in eastern Bosnia. One of the men, Esad Mujanović, managed to jump into the Drina River and flee to safety, eventually finding refuge in Germany.

The bridge executions were typical of the emerging patterns of violence across Bosnia. Serb nationalist forces, aided by the remnants of the formidable Yugoslav National Army, used their might to systematically terrorize, murder, and expel the non-Serb population in an effort to create a new, ethnically pure statelet. They justified this violence as a preventive measure against an alleged specter of Islamic fundamentalism, casting all Bosniaks (who are primarily Muslim) as sources of danger. Within a year, out of some 21,000 Bosniak inhabitants of the Foča municipality, only 10 remained. The triumphant Serb nationalists renamed the place Srbinje, or “Serbtown.”

During the war, when the Bosnian Serb soldier Novislav Djajić traveled to Germany, he was recognized by former Foča residents as one of the paramilitaries standing on the bridge that day. A German court conducted an investigation, gathering evidence and summoning witnesses, some of whom could not testify due to the overwhelming psychological strain of recalling the wartime violence. The court concluded beyond reasonable doubt that Djajić was an accomplice in the murder of the 14 Bosniaks. He was sentenced to five years in prison.

In the 1990s, when the Austrian writer Peter Handke took it upon himself to revise the history of the Bosnian War, he also reinterpreted the Foča bridge murders.

Handke first met Djajić in a German prison and crafted the killer’s story as an example of forgotten victimhood at the hands of foreign courts and biased media. By the time he met Djajić in 1997, the Austrian writer had already made his views on the war clear. In “Justice for Serbia” (1995), he set out to redeem the Serbian nationalist project, indicting international courts and the media, which had allegedly “set up ‘the Serbs,’ far and near, large and small, as the evildoers, and ‘the Muslims’ in general as the good ones.”

Djajić fit Handke’s type. In the “Voyage by Dugout” (1999), a play set in an unnamed Balkan town after the war, Handke casts Djajić as “The Woodsman,” a local seller of “wild honey and mushrooms” over whom a dark cloud hangs: “A couple of times I appeared on international television, like this, with a bottle in my hand, as the third bad guy in the second row from the left. … And after the war I spent five years in a German prison, convicted by a German judge for complicity in genocide.”

Riffing on the justifications rejected by the German court, Handke again turned to Djajić’s story in “Around the Grand Tribunal” (2003), but this time folding it into a nonfiction account of his visits to the Hague Tribunal.

In Djajić, the Austrian had found not just friendship — Handke was the best man at Djajić’s wedding and attended the baptism of his two daughters — but also the key elements for rewriting the factual record of the Bosnian War. In Handke’s telling, Djajić was an idealistic Serb villager who got swept up in the chaos of the war. At a time when killing was rampant, he simply ended up at the wrong place at the wrong time, holding a gun at a mass execution. At one point in “Voyage,” Handke has the Djajić character ponder his responsibility only to conclude: “Knowing that guiltless I was guilty, I said Yes! to my punishment. Punished by the foreign state and despised by my own people, I lost my sense of guilt.”

If there are any unambiguous villains in Handke’s story, they are the foreign judges who mindlessly insist on holding men like Djajić accountable. The outcome is that a misunderstood and sensitive Balkan soul ends up alone with his sorrows, telling the visiting filmmakers, “I’m no longer socially acceptable,” only for them to realize that, “No, society is no longer socially acceptable.” Far from being a “bad guy,” Djajić is a paradigmatic victim.

While he lavishes attention on Djajić, Handke never mentions the Bosnian Muslim victims of the Foča bridge killings. There is no acknowledgement of an organized campaign against non-Serbs. Handke instead insists on depicting the war as the result of chaotic revenge attacks among vaguely defined communities. For Handke, this was “how the whole Bosnian war had gone: one night a Muslim village was destroyed, the following night a Serbian one”; it was “fighting on all sides almost all over Bosnia.” The implication is clear: “all sides” committed crimes until one side somehow disappeared. The war was a matter of indiscriminate violence, creating a maelstrom where everyone was a victim, especially those who were later convicted. By virtue of his sentencing, Handke suggests, Djajić is more of a victim than his actual victims.

To soften the menacing edge of his writings, Handke often casts himself as an unconventional writer, a brave poet, a curious stranger in a strange land who asks disturbing questions only for the sake of peace, justice, or some other universal good.

Handke rarely resorts to cliches about fiction as an independent or amoral realm detached from daily politics. Most of his Yugoslav texts are nonfiction accounts in which Handke insists that his literary interventions should have political consequences.

“And won’t the history of the wars of (Yugoslav) disintegration now be written differently perhaps than in the contemporary assignments of guilt in advance?” Handke announced in 1995. “Who will someday write this history differently, even if only the nuances — which could do much to liberate the peoples from their mutual inflexible images?”

The questions are, of course, rhetorical because Handke was already writing a denialist history — as he did with the Djajić case — by rejecting the factual record, trivializing the victims, and justifying the violence.

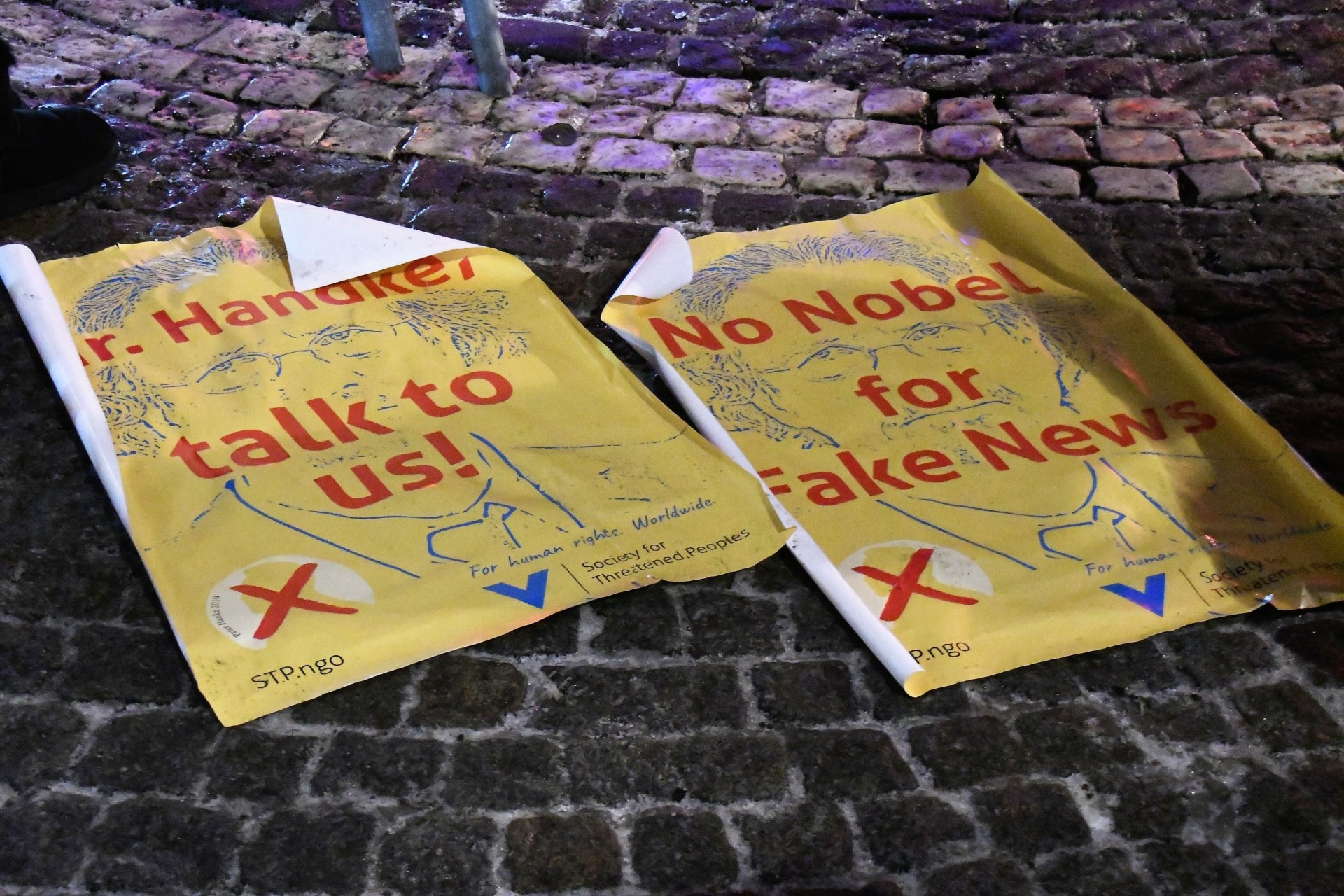

In 2019, Handke was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature.

What does literature have to do with genocide denial?

The controversy around the 2019 award has put that question at the center of ongoing debates about the ethics and politics of contemporary literature.

While the Nobel committee insists that Handke is a poetic genius whose works transcend worldly politics, the Austrian writer’s Yugoslav texts tell a different story.

What Handke has crafted is a new cultural space for genocide denial, blending literary ambiguity and epistemic uncertainty in an effort to rewrite the history of the genocide in Bosnia and redeem the Serbian nationalism of the 1990s, even using the Srebrenica mass murders to advance anti-Muslim views in the name of peace and justice.

The Swedish Academy’s embrace of Handke comes at a time when far-right movements worldwide have also seized elements of 1990s Serbian nationalism as fuel for violent fantasies from Utøya, Norway, to Christchurch, New Zealand. The consequences of this literary-political entanglement will surely be far reaching, and not just for the history of the Yugoslav wars.

In the 1960s, psychologist Israel Charny began to study genocide denial, compiling various strategies used by denialists of the Armenian genocide. Denial was not, as the commonplace notion goes, just a statement, “I deny X happened.” Instead, Charny found that templates of denial mostly begin with a recognition of some deaths and then proceed to create uncertainty about the factual record and replace it with other stories. Most frequent are claims that deaths took place chaotically, implying that they were not organized, and declarations that the victims were actually powerful while perpetrators acted in self-defense or in some other justifiable way.

Crucially, denialists sometimes acknowledge violence in order to appear reasonable only to use that appearance to promote other narratives as plausible alternatives (“now we need to debate this”). It is that pivot that historian Deborah Lipstadt called the “Yes, but …” strategy, one of the most common denialist tropes.

Serbian nationalists officially embraced denialist stances beginning in the 1990s. President Slobodan Milošević’s regime claimed that Serbia was not involved in the Bosnian War and denied that wartime violence was genocidal. After Milošević’s removal in 2000, most of his successors refocused their energies against the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia at the Hague, which had ruled that acts of genocide took place in Bosnia. As Serbian human rights organizations tried to confront the wartime past, the post-Milošević discourse of denial expanded its range from total negation and celebration of war criminals to more sophisticated claims stressing the culpability of all sides, the unreliability of evidence, and the alleged anti-Serb bias of international courts. By appealing to epistemic uncertainty, the denialist discourse was updated from “it didn’t happen” to “nobody knows what really happened, but we know The Hague is lying.”

Many of Handke’s claims about the Yugoslav wars follow this denialist template, thus endearing him to Serb nationalists. Handke does not deny the facts outright, but he casts doubt on them and then restages the war as a series of tragic but inscrutable events that only he can reconstruct once they are freed of evidentiary concerns. His strategy is flexible. When courts verify facts beyond reasonable doubt, Handke shifts the subject and questions the legitimacy of the “foreign” courts, particularly The Hague apparatus, which he vilifies in “Around the Grand Tribunal.” He is preoccupied with redeeming figures like Djajić or Dragoljub Milanović, men who have been sentenced for various crimes. When forced to acknowledge an indisputable crime like Srebrenica, as he did in the aftermath of his notorious speech at Milošević’s grave in 2006, Handke made a point of shifting the focus away from the Bosniak victims toward “the Muslim-perpetrated massacres in the many Serbian villages around the — Muslim — Srebrenica.”

It’s no wonder, then, that Serbian nationalists and Handke have built lasting alliances over the years, from Milošević of the 1990s (whose regime issued Handke a Serbian passport in 1999) to Tomislav “Toma” Nikolić of the 2000s (whom Handke endorsed in the 2008 elections) to the current president of Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić (from whom Handke received Serbia’s highest honors).

Handke’s cult of celebrity has only grown with the Nobel Prize. In 2019, over 100 Serbian writers, academics, and politicians signed a public letter of support for Handke, in which they stated that “there were no genocidal activities” in the 1990s wars (Handke did not disavow their statement). In 2021, Handke traveled again to Serbia and Bosnia to receive more prizes, capping off his visit by attending the state-sponsored unveiling of a larger-than-life statue of himself. In a provincial syndrome common to small nation-states, Serb nationalists revere Handke as the Great White Man who speaks “our truth” to the West. While claiming that he is apolitical, Handke enjoys playing that role and savoring its peculiar power.

Handke’s celebrated achievement has been to create a new artistic position where literary ambiguity and epistemic uncertainty make it possible for a writer to advance denialist claims in the name of peace, justice, or some other cultural good. Like a virtuoso denialist, Handke performs this move with a knowing wink to those who read between his lines. He outlined this space already in “Justice for Serbia,” where his lengthy descriptions of nature along the Drina River yield to a laden question: “A child’s sandal broke the surface at my feet. ‘You aren’t going to question the massacre at Srebrenica too, are you?’ S. commented, in response, after my return.” Handke thinks he knows how to handle such matters: “‘No,’ I said. ‘But …’”

That, in a nutshell, is Handke’s poetic innovation: adapting the “Yes, but …” template to a “No, but …” tour of questions, claims, and theatrical pleas for a radical revision of the factual record. Handke follows his “No, but …” with several pages shuffling between different subjects — “But I want to ask how such a massacre is to be explained, carried out, it seems, under the eyes of the world, after more than three years of war during which, people say, all parties, even the dogs of this war, had become tired of killing … And why, instead of an investigation into the causes (‘psychopaths’ doesn’t suffice), again nothing but the sale of the naked, lascivious, market-driven facts and supposed facts?” — only to return to his view of himself as a courageous explorer on a utopian quest: “I feel compelled only to justice. Or perhaps even only to questioning?, to raising doubts.”

In his Yugoslav writings, Handke is obviously outraged by portrayals that cast “‘the Serbs’ as the evildoers, and ‘the Muslims’ in general as the good ones.” Handke’s resulting narrative is not a simple reversal of those roles. It is not so much the case that “the Serbs” come out as the “good guys.” It is closer to the truth that in Handke’s writings, there are no good Muslims, insofar as there are any Muslims at all.

There is a subdued but unmistakable anti-Muslim animus that punctuates Handke’s commentaries on Yugoslavia. Even in the rare instances when he mentions Bosniaks or Muslims, Handke refers to them in collective and belligerent terms. He sees Muslim refugees in photographs and wonders why they all obey the foreign photographer’s directions; he talks of Muslims — “if they are in fact a people” — as “powerholders long armed for war”; he talks of Muslim “soldiers” in Srebrenica, implying that the murdered civilians were legitimate military targets; he talks of “Muslim mujahedeen” as false equivalents of Ratko Mladić and Radovan Karadžić.

Aside from a rare mention of a high-ranking politician, Handke’s extended writings about places that Muslims inhabit — or once inhabited before the Bosnian War — have no Muslim names, no Muslim characters, no Muslim lives in them. When Handke and his apologists say that his work is about creating a new kind of utopia, perhaps they’re right after all. Handke’s utopia is a place without Muslims.