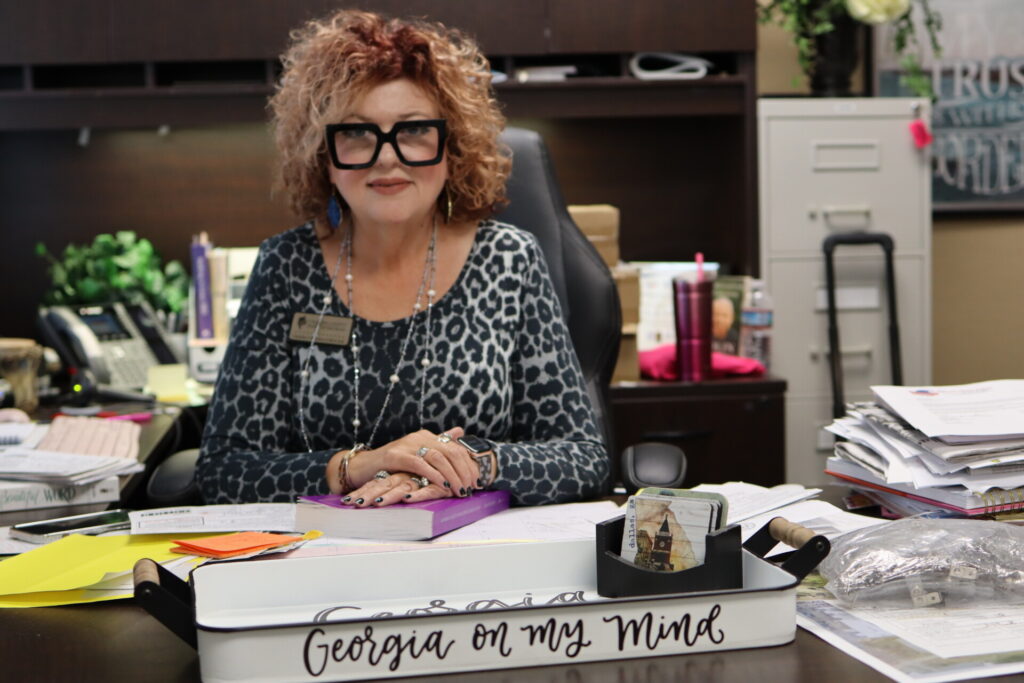

Deidre Holden has been administering elections in the U.S. state of Georgia for two decades, and today serves as the election supervisor in Paulding County, a Republican-leaning county north of Atlanta. She loves working in elections as a nonpartisan administrator. “It is in my heart and my soul and I love doing what I do. I love serving the people. I love serving the voters and taking care of them,” she told me in an interview in her office.

But over the past few election cycles, she’s seen a change in how she has to do her job. “We have to now train on things outside the election realm, as far as safety, security,” she noted. She pointed to the wide range of safety procedures that elections staff now have to be educated on during their annual association meetings.

“We train on issuing absentee ballots and provisionals and how to do this and how to do that,” she explained. But at their last meeting they had been trained by the FBI, and before that had been trained by the Department of Homeland Security and taught how to administer Narcan by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “So it’s not just about voting anymore. It’s about the protection from active shooters, from irate voters to de-escalation to suspicious packages. So it’s not the elections I started out in. It’s definitely different.” Facing an increasingly hostile political climate, Paulding County Board of Elections has installed emergency panic buttons and beefed up its surveillance cameras and security personnel presence.

This tense climate set in after the 2020 election, which former President Donald Trump refused to concede. Instead, he charged, without evidence, that the election had been improperly administered and that a vast amount of voter fraud helped his Democratic opponents steal the election.

Georgia, in particular, was in Trump’s crosshairs. He lost the state by fewer than 12,000 votes. The narrow margin — as well as an avalanche of conspiratorial claims promulgated by Trump-aligned right-wing media — provided fodder for a portion of his base that believed the contest had been stolen from him.

Election workers like Holden and her staff have borne the brunt of those claims. She recalled getting an email shortly before the Senate runoff in January 2021. “It was basically saying — and they were mad because President Trump did not win — that they were going to make the Boston Bombing look like child’s play,” she said. Election officials in several counties received the same email, and although the authorities were alerted the person who sent the missive was never found.

But Holden believed that standing up to the threat and administering the election was her civic duty. “I didn’t want to create mass panic because if I would’ve done that, that would have kept people from voting. And they would’ve won at that point. That would’ve been, OK, I got them to do what I wanted,” she said.

Georgia Republicans went on to lose that runoff election, just as they lost the presidential election in the months prior. Trump had tried to pressure statewide Republican elected officials to “find” additional votes for him so that he could win the presidential election, but Georgia’s governor, Brian Kemp, and Secretary of State Brad Raffensberger — both Republicans — stood their ground.

Kemp and Raffensberger “were more concerned with the truth than with the result,” explained Scot Turner, a former Republican state representative who today works at a nonprofit called Eternal Vigilance Action. An incensed Trump recruited candidates to try to unseat Kemp and Raffensberger in 2022. But his gambit failed. Both men easily beat back their Republican primary opponents and then sailed to reelection.

But many of Trump’s most diehard followers refused to let go of the idea that the election was stolen. This wing of the Georgia Republican Party may not be in control of the elected offices — where lawmakers resisted Trump’s scheme — but they do have a Make America Great Again (MAGA) activist contingent who have continued to undermine conservative faith in Georgia’s elections.

Since the summer, for instance, these activists have challenged the voter registrations of over 63,000 Georgians. If successful, these challenges would result in these voters being removed from the rolls. But fewer than 800 were actually removed or placed into challenged status (where voters can still vote if they produce documentation proving that they are at their Georgia residence).

They also pushed for, and received, many audits of the previous Georgia election — which found no proof of widespread fraud. One recent audit of noncitizen Georgia voters found that, out of 8.2 million registered Georgia voters, just 20 were noncitizens (and not all had even voted).

The last-ditch effort by Trump-aligned activists to change Georgia voting rules came from the State Election Board, a once-obscure entity that recently gained a MAGA majority determined to put into place regulations that they believe will prevent Democrats from stealing future elections. Trump himself has praised the three election board members who are aligned with his movement.

In the weeks leading up to the start of early voting in Georgia, the board called for new powers that would, among other things, give county election boards the ability to delay certification — which could not only throw Georgia’s election into chaos but also buy time for Trump to sow doubt about any elections the Republicans lose this year.

But Georgia’s courts dealt the State Election Board a loss before voting began, ruling that Georgia’s legislature, and not the board, is the entity that has the power to make these voting rules. This effectively invalidated the MAGA majority’s plan to influence the election.

In a twist that demonstrates the dynamic at play in Georgia today, one of the men who led the lawsuit against the board was Turner, the former GOP state representative. I asked him why he felt compelled, as someone who has spent his life in the Republican Party, to sue Republican-backed officials. Fresh from winning in court, he told me that his biggest concern was the country’s long-term health. “And I can foresee a time when Democrats will be in charge of the state election board, and Republicans will be wondering, why are we legislating through this nonelected bureaucratic board?”

But he also pointed to deeper principles at play. “I feel like constitutionally there’s a separation of powers question, this conservative principle of constitutionality on everything, and they were violating that,” he said. “And they were doing so with their eye on this election instead of every election going down the line. And it was shortsighted. So as a Republican, I decided to engage on those grounds. … People who are making the law should have their name on a ballot, not counting the ballots.”

Turner is not an aberration. In a shock to many national observers, the people who have been at the forefront of preventing MAGA chaos in Georgia since 2000 have been Republicans. From Kemp and Raffensberger down to rank-and-file lawmakers like Turner, it has been Republicans themselves who have been defending the integrity of Georgia’s elections and pushing back on conspiracy theories like those that have rankled Holden’s office.

Natalie Crawford, a Republican who served as a county commissioner for two terms in Habersham County, has been working to educate people about the electoral process in Georgia and push back on viral conspiracy theories.

“There are those of us who have done a lot of work to review records and understand there wasn’t widespread voter fraud, that the election was not stolen,” she told New Lines. “We are living in a very hyperpartisan climate and dynamic right now in politics. We’re trying to speak with reason and logic and put the facts in front of folks in hopes that they will check some of this hyperpartisanship and understand that OK, maybe my preferred candidate didn’t win, but the election was secure. The integrity of the election was sound.”

Turner suggested that the MAGA movement’s attacks on Georgia’s elections are emanating from hardcore activists disconnected from the majority of Republican voters. He pointed to the fact that polling done during the state convention of the party suggested that Kemp and Raffensberger would lose their primaries. “Brian Kemp was losing to [primary challenger] David Perdue. And then he smoked him by 52 points,” he recalled, referring to the conspiracy theorists as a “loud minority.”

Yet that loud minority can still cause problems for election workers like Holden. Right-wing pundits and allies of Trump have, at times, singled out individual elections staff, accusing them of being involved in election-stealing conspiracies — creating a climate of fear for many of these workers.

Occasionally, these MAGA figures get their comeuppance. New York City mayor-turned-Trump-loyalist Rudy Giuliani was recently ordered to surrender personal assets to satisfy a $148-million defamation judgment made against him for false claims he made about two Fulton County elections workers. Those workers will soon have access to his luxury watches and a 1980 Mercedes that was once owned by a movie star.

One irony in Trump’s antagonism toward Kemp is that the Georgia governor endorsed him in 2020 and has endorsed him again in 2024. The backing of the popular governor — whose approval rating sits north of 60% — is likely to give Trump an edge in the state.

Yet after the many lies Trump told about Georgia, some former GOP elected officials can’t hold their noses and vote for him anymore. John Pezold, a Republican former state representative, told me he will be voting for the Democratic presidential ticket for the first time in his life, in protest against Trump’s behavior. “I’m not going to put a sticker on my car. I’m not going to put a sign out in front of my house. Just, God, I’m tired of it,” he said.

While Georgia’s elected Republicans have, by and large, resisted Trump’s conspiracism and marginalized the MAGA activists who wanted to overturn its election, they’ve also faced criticism from Democrats.

Following the 2020 election, Republican lawmakers assembled an elections law, Senate Bill 202, that they passed in 2021. Among other things, the bill shortened the period of time in which voters can request absentee ballots, required voters to use ID numbers rather than signatures to verify those ballots, sped up county processing of mail-in votes and expanded in-person early voting access.

Turner acknowledged that the law was passed partly to address the sharp drop in GOP voter confidence. He pointed to 429,000 Republicans who voted in the presidential election but didn’t return for the Senate runoff election between Perdue and fellow Republican Kelly Loeffler and the Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock, noting that polling suggested that many of these people believed that the election had been stolen from Trump.

“That’s a problem for democracy. … The government has an interest in trying to reassure them that their vote’s going to matter,” he said. “It is a form of voter suppression to not address their claims, even if their belief is derived from a false premise.”

But Democrats took aim at certain provisions in the law, including a new one that barred the provision of food and water within a certain distance of a polling place (poll workers would still be allowed to provide water). Democrats argued that some voters may simply give up rather than stand in long lines where outside groups could not quench their thirst or hunger.

President Joe Biden likened the law to Jim Crow. Major League Baseball pulled their All-Star game from Georgia in protest. 2022’s Democratic gubernatorial candidate, Stacey Abrams, called Kemp and Raffensberger the “architects of voter suppression.”

One reason why the Democrats may have used such strong language to describe the law was that they were trying to pass their own federal voting overhaul — the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would extend federal oversight over elections with the intention of preventing suppression. By criticizing GOP-passed laws, the Democrats could build support for their own while also pushing back on what they believed to be Republican voter suppression.

The Republicans interviewed for this piece — all of whom strongly rejected Trump’s conspiratorial claims — chafed at the accusation that their party was trying to suppress the vote.

Marc Hyden, a conservative and former staffer in the Georgia state senate who today works as the Director of Government Affairs at the nonpartisan R Street Institute, called the Jim Crow claims a “really unfair comparison,” saying “You look at these reforms that require you to have an ID to vote, change the number of days that you can send in a mail-in ballot — these are not the same. These are apples and oranges.”

Winters, who had spent so much time this year pushing back on MAGA conspiracy theories, argued that voting in Georgia hasn’t been impeded by the new law. “Georgia has a pretty lengthy early voting period. We have no-excuse absentee voting. We have really good access across the state,” she said.

Turner suggested that election denialism is more bipartisan than is often portrayed. “Both sides are engaged in a long-term strategy of questioning the results,” he lamented.

While that claim may seem objectionable to those who view Trump as the sole culprit in delegitimizing elections, it should be recalled that when Abrams ran in 2018, she refused to concede the election, saying that the state’s voting laws were unfair and impeded the vote.

Holden has seen skepticism of her elections administration from both sides. She described one woman who was unable to get her absentee ballot because she sent the request to the wrong address. “She’s screaming on the phone at my staff and then I talked to her, and then the comment that came out of her mouth before she hung out was: ‘You probably all voted for Trump.’”

If Senate Bill 202 suppressed the vote, it would be very hard to find any evidence of it. Survey work done by the University of Georgia following the 2022 midterm elections, which took place after the measures were implemented, found that 95.5% of Georgians said they had an “excellent” or “good” experience voting in the election, including 96.2% of African Americans.

Just 1.2% of Georgians said they waited more than an hour to cast a vote. Among Black Georgians, that percentage dropped to 0.6%. Most voters said they waited less than 10 minutes or did not have to wait at all.

Even the Kamala Harris campaign seemed to acknowledge that voting in Georgia wasn’t so hard. In a post to X (formerly Twitter) during the first week of early voting, the campaign’s Georgia account posted a short video of a voter boasting about how easy voting was. “Early voting was a breeze for Seth!” it said, encouraging more people to get out to vote.

Still, distrust in Georgia elections is higher among Republicans than Democrats. An Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll released in October found that 39% of Georgia Republicans were “not so confident” or “not at all confident” that the 2024 election “will be conducted fairly or accurately.” Among Democratic voters, that number was 16%.

Georgia voters smashed records during the first days of early voting. After a little more than a week, 2 million Georgians had cast their ballots, a strong turnout considering that around 8 million Georgians are registered to vote.

Lines were manageable for most. At the Paulding County voting location I visited to meet with Holden, it was Oct. 15, the first day of early voting. Holden told me that their average processing time for each voter was less than 30 seconds. One voter she spoke to said it took them about seven minutes in total to vote. Despite the chaos of the past few years and the accusations of voter fraud and voter suppression flung by politicians on both sides, Georgia’s election happens to be going swimmingly — at least so far.

Turner told me he thinks that Georgia will be able to escape the funk of election skepticism eventually. “I think over time, if we’re able to get through enough elections where the candidates who win aren’t trumpeting the stolen election stuff, the conspiracy theories, that we can get through it,” he said.

Holden acknowledged that there were real mistakes made in 2020 — for instance, some counties found additional votes that they had initially failed to count, even though it made no difference to the outcome of the presidential race — but those mistakes were in other counties. “I think that just because certain counties did things incorrectly, we shouldn’t have to be put through the things we are because of that,” she said.

She and her staff have been willing to walk concerned citizens through the voting process, including looking at the machines that are used to tabulate votes. Paulding County also does a full audit of all the votes after elections. Holden desperately wants to win back the trust of the voting public that has been sapped since 2020.

Toward the end of our conversation, she described being interviewed by a Japanese television station. She saw that the political climate in that country is nowhere near as acrimonious as in the United States.

“I think politics is the reason why our nation is so divided right now. I think that there’s just too many things that have happened that have gotten people hardened and mad, and it shouldn’t be that way,” she said. “People shouldn’t fear coming to vote. People shouldn’t fear speaking out. But you can do that in a kind way.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.