Every once in a while, you come across a story in music media with some variation of the headline “Artists React.” I’m not sure how I became a staple of this genre, but I am often mentioned in them alongside musicians with much higher profiles. Sometimes they even include a Hollywood celebrity or two. For an instrumentalist respected mainly by other musicians and known primarily through musician-targeted publications, I may not be a natural fit for such high-visibility company. But I can speculate on the reasons.

For people who earn a living in the performing arts — a gig economy, with “gig” having more than one meaning for musicians — it is a fraught prospect to speak about polarizing subjects and potentially alienate a part of their audience. At a time when everyone is obsessed with follower counts, all it takes is one opinion deemed disagreeable for someone to hit “unfollow.” It is understandable for artists to tread carefully in this digital minefield, so many err on the side of restraint. Perhaps it is for this reason that when a musician chooses to express an honest opinion, it is now deemed newsworthy.

But wasn’t expressing oneself honestly the whole point of becoming an artist?

We are living in a time when the dark dystopias imagined by George Orwell and Aldous Huxley, and more recently by Margaret Atwood and David Foster Wallace, no longer seem far-fetched. One can’t read “1984,” “Brave New World,” “The Handmaid’s Tale,” or “Infinite Jest” without finding echoes of their degraded universes in our current social and political climate. No side has a monopoly on bad ideas, and I don’t automatically agree with everything on the left, especially on its fringes. But to compare its shortcomings to what has become of the contemporary right is to engage in false equivalence. From the MAGA movement, its Republican appeasers, the right-wing media ecosystem, QAnon, white nationalists, the “Alt Right,” to the conservative donor class, antidemocratic sentiment seems to have been embodied in a former TV star who is literally worshipped in golden effigy.

To borrow from Will Ferrell’s character in “Zoolander”: Authoritarianism is so hot right now.

Can one look at the absurdity of it all and choose silence? Should we withhold support for ethical or worthy causes because it may run afoul of someone’s prejudices? Should artists become hostages to their audiences?

There are many impressionable people — many of them well-meaning — who have been lured by the sirens of authoritarianism. In times of crisis, people often fall prey to demagogues promising magical solutions. If we can help steer some of them away from this destructive path, is it really a transgression? Are artists not citizens first?

I feel that the platform I have confers a certain responsibility. My reactions to current events, debates with opinion-makers, jousts with trolls are part of my civic responsibility. I want my listeners and followers to know where I’m coming from. That this makes me an outlier says more about our increasingly risk-averse, apathetic culture than it does about me.

In the mid-2000s, The Dixie Chicks (now known as The Chicks) were blacklisted by their own fans, radio stations, and virtually the entire country music establishment for criticizing George W. Bush, who was then president, over the Iraq War. Without any hint of irony, this same demographic would champion former President Donald Trump for saying the same things about Bush and the war and turn into doomsayers about the threat of “cancel culture” (albeit from the left). Regardless, the incident marked a culture war milestone: It was the 21st century’s first and, by the looks of things, a herald of many more to come. Its ripples are still felt and have contributed to many artists’ trepidation about treading into political waters.

This is especially true for those of us who are fortunate enough to earn a living as full-time artists but who are not part of the invulnerable 1%. We don’t have as much to lose, but we also risk gaining less. As we constantly hustle to build our fan base, I can understand the hesitancy in doing anything that might shrink it. But such fear makes many sell themselves short and potentially compromises their art. One needn’t search far to find examples of formerly outspoken artists, especially those who’ve risen through the ranks into high tax brackets, now churning out unchallenging material like watered-down versions of their former selves.

As artists, we must aim for a base that supports us for who we truly are — imaginative, dynamic, complex human beings, with various dimensions to our personality including, yes, a political one. We can’t all be one-dimensional production units. In order to retain our artistic integrity and gain this type of audience, we must be willing to lose a few followers, especially the kind who want to make our creativity subject to their preferences.

True artistry includes challenging your fans on occasion.

True artistry includes challenging your fans on occasion. Some will come along and discover new ways of seeing. Others will prefer the comfort of their prejudices, hurl insults, and hit “unfollow.” At a time when attention has become a prized commodity, the fear of losing one’s audience is understandable. But we forget that it was fearless acts of imagination that built that audience in the first place. If there are risks to political activism, there are also gratifications to offset them. Every time I have spoken out on a political issue, I’ve alienated a few. I have also had my views amplified by journalists and opinion-makers, some of them household names. This in turn has brought me to the attention of people beyond my immediate audience — new follows, more retweets. The biggest loss to me would be to succumb to fear and suppress my voice at a time like this.

Ironically, rock used to be all about bold statements. From Jimi Hendrix’s “Machine Gun” (about the Vietnam War), Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War” (about the “military-industrial complex”), Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s “Ohio” (about the Kent State massacre), Black Sabbath’s “Into the Void” (about the space race), Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi” (about environmental degradation), Sting’s “Russians” (about the Cold War), U2’s “Sunday, Bloody Sunday” (about Northern Ireland’s “troubles”) to Metallica’s “One” and “Disposable Heroes” (about the human cost of militarism) — musicians seemed unafraid of speaking their political convictions. It seems ironic then that audiences have grown so intolerant of dissenting opinions among artists when so much of the music they grew up with is defined by it.

Part of my motivation in pursuing music in the first place was to not be forced to suppress that which I wanted to express. I wouldn’t have lasted long in a regular job that requires you to bottle up your feelings, put on a happy face, and suck up to those on whom your income depends. The 1999 Mike Judge film “Office Space” deftly satirizes such an environment. And in some respects, the hordes of disgruntled social media followers who respond to your political tweet with some version of “Stick to guitar!” are trying to impose a similar type of conformity on the nonconformist world of an artist.

To use one’s platform merely for announcing events, flogging merchandise, or talking guitars and not to comment on that day’s political event, environmental catastrophe, or health crisis would be a moral abdication. It would be to detach oneself from the experiences that inspire art. It would be like carrying a frozen smile — like the workers in the stifling, fictional universe of “Office Space” — to hide the maladies that diminish the human experience of citizen and artist alike.

The fans weren’t always like this — and neither was I.

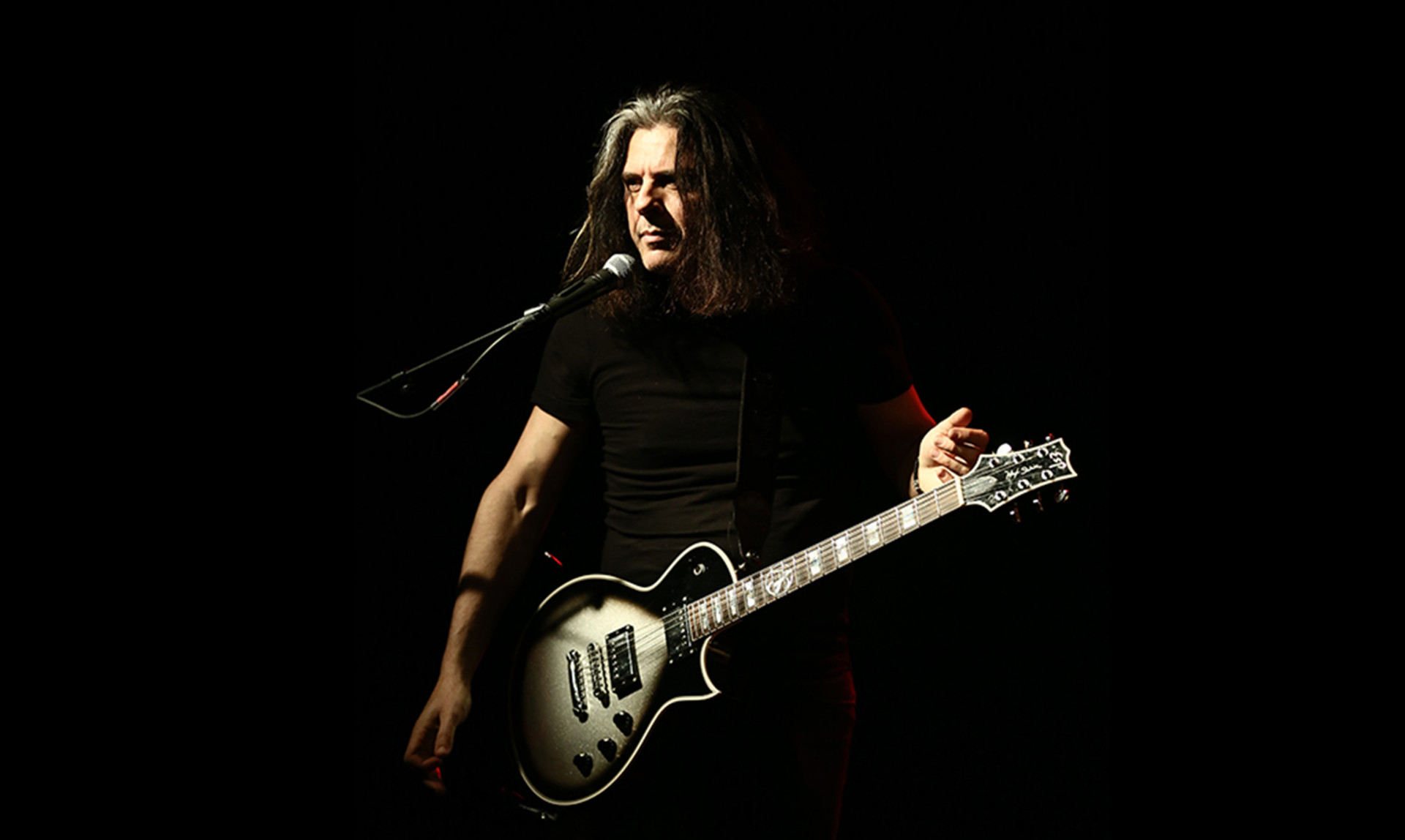

I grew up wishing to avoid confrontation, to receive approval, and just blend in. Some are born with the gift of the gab. All I carried into my early adulthood was a psychological lump in my throat. For the introverted, our best hope is to develop alternative means of expression that make up for our lack of loquaciousness. In my case, the means was a six-stringed instrument wielded by people who, at various points in recent history, have been considered offensive to polite society. As a teen, the electric guitar became my channel for releasing pent-up emotions. In addition to giving me a creatively satisfying career, the guitar helped me overcome my extreme shyness and diffidence.

As an adult, music would take me around the world many times over and introduce me to people, places, and experiences that I’d have never known otherwise. This certainly helped inform my worldview. I’ve often been struck by those who force their “patriotism” on others by claiming “America is number one!” Most have never left the country.

Those who are more familiar with my work in jazz and world music, or as an educator, are sometimes surprised to find that I became a professional musician at age 18, and my pathway to recognition was secured through the subgenre of thrash metal — a style of music for which I’m still best known. The confusion perhaps stems from the fact that I don’t readily fit the stereotype associated with that style of music. While many in the metal world came from working-class backgrounds, fighting family expectations to fit in, get a haircut, and work a “real job,” I was rebelling against expectations of an academic career. I grew up against a backdrop of Freud, Foucault, faculty meetings, grant proposals, and sleep-inducing PBS programming.

I never saw anything unusual about my background in the Bay Area music scene. As young rockers and metalheads in the 1980s, we were all rebelling against something, above all our parents’ expectations. Kids raised by union members were rebelling against the pressure to become machine laborers, and those raised by Ivy League Ph.D.s, as I was, were escaping the specter of academic drudgery. It did not matter whether we came from the coast or the heartland, city or countryside. There was no blue vs. red, left vs. right, liberal vs. conservative, or any other polarization — just rockers vs. “model citizens.”

We were united in our alienation, in our inability to fit with convention, and in our desire to express ourselves freely and follow our own paths. Politics did not play a part. Politicians were just like the other P’s: Parents, Police, Parishioners. They hated our hair, our clothes, our music. It was “Them or Us,” to borrow from an album title by an artist who would become the ultimate role model of an intelligent, informed musician unafraid to speak his truth no matter how controversial: Frank Zappa.

In the mid-1980s, Zappa was at the heart of a seminal event in rock history — the Parents Music Resource Council (PMRC) hearings in Washington, D.C. The PMRC consisted largely of the spouses of powerful politicians, and the PMRC hearings were the encapsulation of “them or us” when it came to rock music vs. the world. They were concerned parents and politicians (mostly white and conservative), targeting artists from Prince and Madonna to Judas Priest and Ozzy Osbourne. Although largely conservative, their movement was led by both a Republican (Susan Baker, wife of then-Secretary of State James Baker) and a Democrat (Tipper Gore, wife of then-Tennessee Sen. and future Vice President Al Gore).

Zappa’s own eclectic music may have been quite different from that which he was defending, yet he nonetheless answered the call to be unofficial “lead counsel” for the popular rock music under attack (his testimony buttressed by such unlikely accomplices as John Denver and my friend Dee Snider of Twisted Sister). It was a battle between the so-called decent folks and the behavior they rallied against: loud music, loud clothing, long hair, colorful language, and explicit topics; the impulsive, the indecent, the sexual, and the primal.

Fast forward a few decades and conservatism looks a lot different. “Decency” is no longer a conservative cause. At first this seems like a good thing. Loud expressions of hair, clothing, and music no longer seem threatening. Cannabis has been legalized in numerous states. But the few gains have come at the price of increased anti-intellectualism, science denial, ideological intolerance, xenophobia, racist dog whistles, and the open acceptance of grifters and abusers to places of power. Lifestyles once considered “alternative” have been largely destigmatized, but backlash politics has transposed old prejudices onto a tribal plane.

The number of rock fans who have embraced modern right-wing causes is shocking. I hear from them every time I express a political opinion. I am accused of “socialism” whenever I speak of fair wages and affordable health care. I am labeled a “Communist” when I speak of tech companies who have irresponsibly amplified provocateurs like Alex Jones or the now former U.S. president. Some of the biggest attacks have come from posts in which I’ve said nothing at all, such as when I was photographed performing in Texas wearing a “Beto” pin (during Beto O’Rourke’s Senate campaign) or with my arms around Sen. Elizabeth Warren and former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Julián Castro at a campaign event. The responses are never substantive. I am a “libtard,” “Commie” or “radical leftist” for speaking of the proliferation of assault weapons in America. Meanwhile, when I used my own preferred method of shooting — a Leica DSL camera — to capture the massive crowd attending a 2019 speech in New York by teen climate activist Greta Thunberg, I was accused of perpetuating a “hoax.”

The sensibilities of this crowd are easily offended despite their tendency to label ideological opponents as “snowflakes.” Their rhetorical armory is supplied with darts and arrows from Tucker Carlson, Sean Hannity, Ben Shapiro, Candace Owens, and other culture warriors. Their comments on the issues seem largely replicated from these right-wing echo chambers, with little evidence of original thought and knowledge.

Quite a few fans of Testament have threatened to stop listening to the band as a direct result of my mainstream, left-of-center views. Such threats seemed to peak in the wake of my most notorious moment: a self-produced, comedic rap video titled “Trump Sucks,” released prior to the 2020 U.S. election. The track — one in which I proudly wear Zappa’s influence on my sleeve — was thankfully found to be hilarious by the other members of Testament. Although I wouldn’t blame them if there was cause for concern, they’ve been generally supportive, and the old adage of there being “no such thing as bad publicity” has held firm. Meanwhile, the band seems to have suffered no noticeable decline in user engagement as a direct result of my political moonlighting.

Though some notable musicians had slipped into reactionary politics in the 1970s and 1980s, most remained apolitical. Had you told me back in the PMRC days that this many rockers — including a disturbing number of my own fans — would be on the same side as the evangelicals, the climate deniers, the NRA, the police unions, the Heritage Foundation, the Koch brothers, the Mercer family, the Federalist Society, and other conservative organizations, I’d have found it laughable.

Similarly, if the rebellious teenage self could peer into the future, he’d likely be proud of his musical accomplishments but horrified at how closely his news consumption resembles that of his parents: subscriptions to The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and more.

I suppose that with lived experience, the same subjects I’d once found boring, particularly politics and those concerning human behavior, have become more interesting and even essential. At some point politics became inescapable, even existential. The melting of polar ice caps, the open carrying of paramilitary assault weapons on U.S. streets, and even mask-wearing during a pandemic — how did all of this become politicized?

While playing guitar was once my youthful act of rebellion, today I’m rebelling by merely expressing how I feel about what is going on in our world. Guiding me and others who think like I do is the spirit of Zappa, whose dissonant musical explorations have had less of an influence than his honesty and artistic integrity. He set the bar higher than the wall Trump tried to place on the U.S. border.

Among Zappa’s numerous albums was an instrumental LP titled, “Shut Up ‘N Play Yer Guitar.” Ironically, this phrase has been expropriated by right-wing censors trying to silence me and other artists — ignoring Zappa’s own legacy and intention. At a time when online algorithms, media echo chambers, trolls, and other sources of disinformation are erasing nuance and increasing friction, the ambiguity and dimensionality that gives art its depth has itself fallen prey.

We don’t have to agree on everything. We can accommodate differences and respect each other’s preferences, as long as we start from a premise of good faith and shared reality. To quote American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Music is a universal language.” By reaching into the depths of the human psyche, the best kind of music resonates across very different lived experiences. It can only be hoped that through listening, both verbally and musically, our notions of truth once again find harmony, and instead of fearing dissonant notes, we learn to assimilate them, as the greatest of composers once did.