A large white warehouse towers over Douma, northwest of Damascus, the Syrian capital. Long, dusty roads wind their way up to this solitary structure, standing tall in the vast emptiness of brown mountains. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) fighters stood guard at the entrance and demanded a press permit from one of us to enter the factory, which our fixer said was understood to make “Captain Corn” chips during the reign of former President Bashar al-Assad. The irony of the name — strikingly similar to that of the amphetamine-like stimulant known as Captagon — is not lost on us.

In 2015, reports by several media organizations documented significant Captagon production within Syria. For many years, the Assad regime thrived on the drug; a 2022 AFP report estimated the value of its market at around $10 billion in 2021.

On our way to the factory, we asked multiple people on the road for directions. Often, they would guide us. Three weeks ago, speaking out loud about Captagon, closely associated with Assad and his supporters, would have been inconceivable.

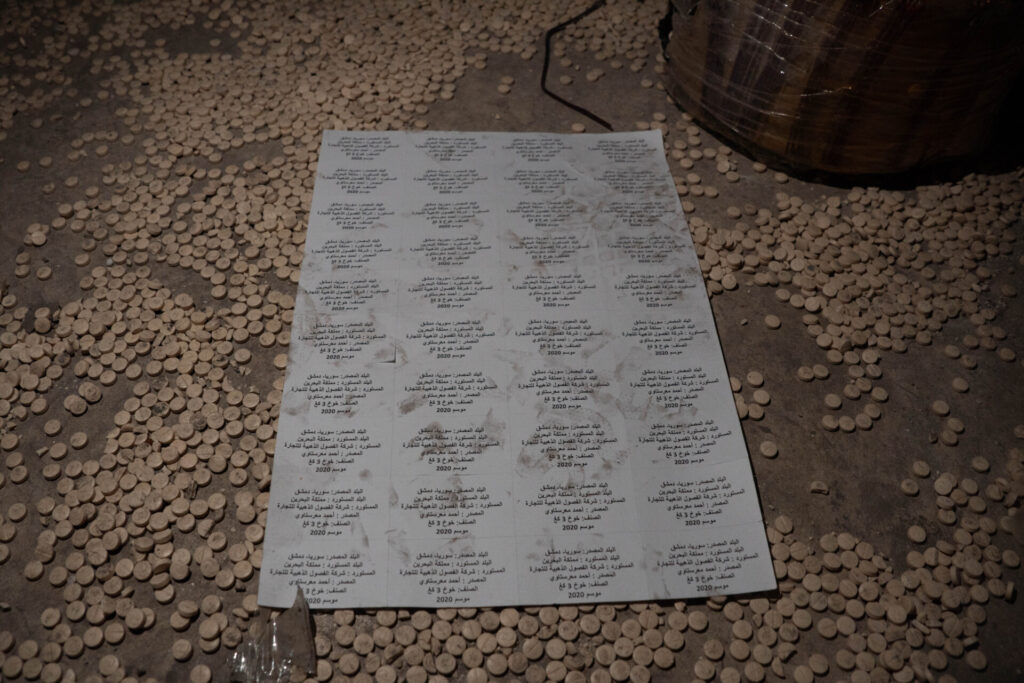

Inside the building’s basement, millions of white pills were scattered across the floor, stretching as far as the eye could see. The first ones we noticed were lying on an old Syrian flag being trampled on by a rebel. They repeated this gesture in front of the cameras of other journalists several times.

“This is the largest Captagon factory we’ve found so far,” said Khalid, an HTS member from Idlib who accompanied us on the tour.

Since the fall of Assad on Dec. 8, the rebels have discovered dozens of complexes dedicated to the production of this drug.

“With the discovery of these massive warehouses, we’re getting an impression of the scale of this trade for the first time,” said Dr. Christina Steenkamp, a reader in social and political change at Oxford Brookes University and author of the report “Captagon and Conflict: Drugs and War on the Border Between Jordan and Syria.”

“There is no way this could have happened without very clear and strong links to institutions of the state,” she added. “That’s what makes it a narco-state.”

Before becoming the illicit substance it is today, Captagon was a legally marketed medication in many countries until the 1990s. In its illegal form, the drug is used largely as a performance enhancer, which creates euphoric effects in the consumer.

Captagon has a long history of production in the region; before the Syrian civil war, its production was centered in the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon, a stronghold of Hezbollah. With demand concentrated in the Gulf states, exports were made either via sea, through Lebanese ports, or by land through Syria.

By 2017, following Russia’s decisive intervention in Syria’s war, Captagon production came under the regime’s control. According to several experts, it became clear that the drug production zone had shifted from Lebanon to Syria. Tons of Captagon were produced daily in numerous warehouses guarded by Syrian soldiers, particularly those of the 4th Armored Division under the control of Maher al-Assad, Bashar’s younger brother.

Intending primarily to export the drug, the regime employed countless smuggling techniques to bypass foreign customs controls. In the Douma warehouse alone, we counted nearly 10 methods, including fake fruit made of polystyrene, tahini cans, electricity meters and LED lamps, all used to transport the pills over borders.

In the factory, we were shown buckets of silicone and an orange, crystalline product that we couldn’t identify. It is highly possible that the ingredients were used to produce the prized drug or others. The dark, dingy conditions inside the factory belied how much money we knew we were surrounded by.

Before 2017, armed groups were financing themselves with the drug, using the profits to buy weapons or pay fighters.

“We must remember that there has always been a well-established link between violent conflicts and organized crime,” Steenkamp said. “One of the best ways to make money is to engage in organized crime. It can be through diamonds, illegal mining for minerals or drugs, as we’ve seen in Afghanistan or Colombia in the past.”

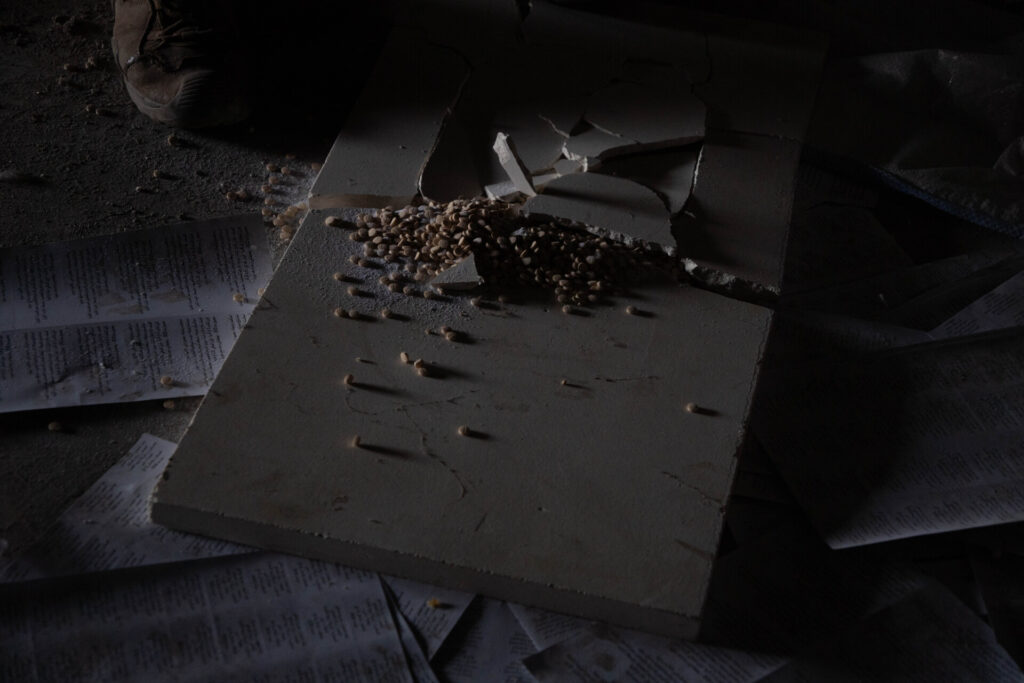

While Khalid and his colleague Muhammad, an HTS fighter from Aleppo, were rummaging through the boxes and electronics on the floor, searching for more hidden stashes and explaining their role at the factory to us, Khalid struck some plasterboard leaning against a wall. It broke open and hundreds of Captagon pills streamed onto the floor.

His eyes widened in surprise and his voice rose, as he realized they’d just discovered another smuggling trick.

“It’s like this every day,” he said. “We keep finding more Captagon.”

About 15 guards remain on-site around the clock, rotating every three hours. The work is physically taxing: The sharp stench of chemicals affects their breathing, they experience headaches and cough frequently. When we left the warehouse, our eyes were watery and we could feel a sharp contrast in the quality of the air that we were breathing. Assad’s “gold” is toxic for the rebels but it was vital for the Syrian regime.

Caroline Rose, director of the New Lines Institute’s project on the Captagon trade, said the Assad regime was heavily reliant on Captagon exports for its income and that profits were used to “line the pockets of regime-aligned individuals.”

“Captagon revenue helped them undercut the feeling and effect of sanctions and sustain the regime’s power base,” she explained.

As the Captagon trade garnered more international attention over the years, the traffickers switched away from relying primarily on maritime routes and began to move the drug more by land. Their methods and means of hiding the pills became more sophisticated as well, as we witnessed ourselves in the warehouse.

“The geographical position of Syria, the fact that it is close to the market, which is mostly in the Gulf area, gave an opportunity to invest in Captagon,” Steenkamp said.

In addition, Steenkamp highlighted the role of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, which brought valuable expertise to the operation. “They had Hezbollah, who had experience in this field and could help them develop the trade,” she said.

Syria’s infrastructure, with its strong road network and established pharmaceutical industry, further supported Captagon production. “They had people who knew how chemistry works and how to set up labs,” Steenkamp noted. “For all these reasons, it was an obvious solution for Assad’s problems.”

Captagon is more popular in the Middle East than anywhere else in the world, a fact that may seem puzzling at first, given that societies in this region are often seen as having a certain conservatism when it comes to drug consumption. The counterfeit version produced by the Syrian regime bears little resemblance to the original chemical composition and is even more dangerous, but the drug’s tablet form can still be reassuring to users.

“It’s not like injecting or snorting a line of cocaine. It doesn’t look as scary as other drugs. In many countries, including Syria, Jordan and Saudi Arabia — the places where the big market is — it has lost much of its social stigma,” suggested Steenkamp. “In many communities, using Captagon is no longer seen as a major problem — it is widely used and available.”

When we were at the factory, we found a prayer mat lying among the tiny white pills. One of the rebels picked it up. “They’d produce drugs, and then at the end of the day, do their prayers,” he said disdainfully.

With multiple labs being found around the country, what HTS will do with them remains an open question. Rose believes that raiding these labs is an easy way for it to build support and goodwill among the masses.

“Given sanctions relief and delisting of HTS is now on the line for the group, they know that if there was any evidence of their participation in drug production, that would really risk their status and relationships they’re building with international actors,” she said.

When we asked Khalid and Muhammad what they were planning to do with the facility, they said they hoped to hand over this particular warehouse to the factory owner from whom it was allegedly seized. They told us this was an endeavor they were yet to start, as they were waiting for journalists to finish their press visits.

While HTS’ stated goal is to eradicate Captagon production and erase this chapter from Syria’s history books, the reality of enforcing it may not be as straightforward. The group does not control all of Syria and, as long as that remains the case, it may prove difficult to prevent other factions from capitalizing on this lucrative trade.

Even if HTS succeeds in destroying all the factories and eliminating Captagon supply, demand for the drug would remain unchanged. The power wielded by the little pill is still as strong as ever, and the expertise developed in Syria in recent years may well continue to thrive, regardless of HTS’ efforts to weaken it.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.