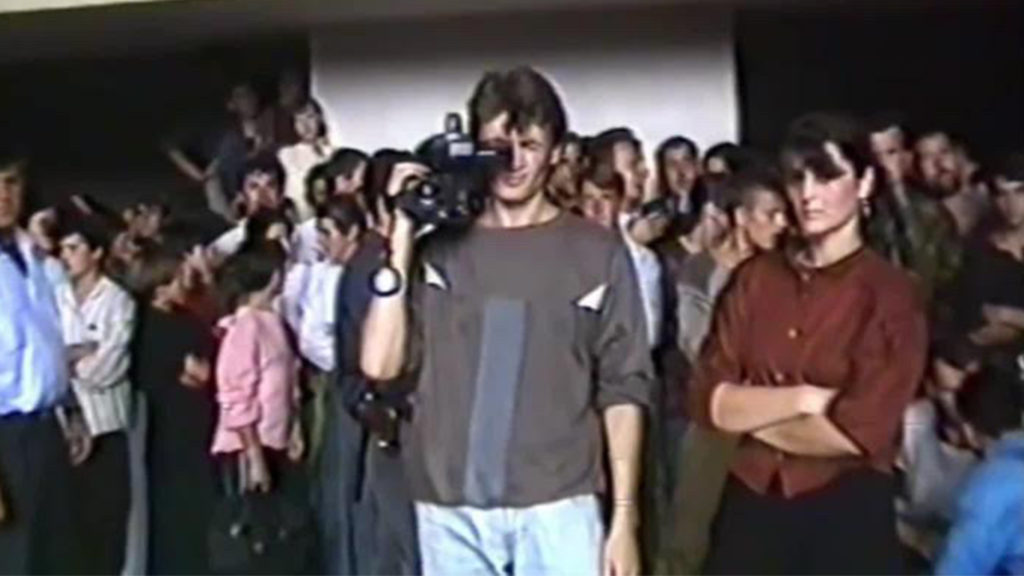

Ibro Zahirović was the only Bosniak who was filming Srebrenica on the day in July 1995 the enclave fell to Serb forces. Born on July 25, 1969, in the village of Hrnčići, in the municipality of Bratunac in eastern Bosnia, he was the son of a well-known master radio and TV mechanic, and followed in his father’s footsteps. During the two years he spent in Sarajevo, the state capital, he would buy every book about electronics he could find. He performed his obligatory military service in December 1988 and started a private radio TV service in Konjević Polje, a village 12 miles east of Srebrenica. He worked there until April 15, 1992. That’s also when he got his first video camera.

At the beginning of the war in Bosnia, in spring 1992, Ibro had an opportunity to leave. His father, who was living in Germany at the time, arrived for Eid to take his wife and children. Ibro’s five siblings left, but he stayed because his wife didn’t have a passport. “To be honest, at the time, I didn’t even feel like going,” he told New Lines, “though had I known what would ensue, I would have left with them.”

Ibro would listen to news on the radio in his car until the battery and the fuel ran out. That’s when he took a bicycle and connected it to the car radio. He then had kids from the neighborhood turn the pedals so they could listen to music and news. Ibro started thinking about building a mini power plant on a nearby river called the Kravica. He had a riverside cottage and immediately threw himself into work. He took the washing machine from the house and used a drum to install the fins. The belt would then move a car alternator, which produced 12 volts, enough to charge the car and other batteries.

That’s how Ibro charged his camera battery and started spontaneously recording events around him. One early recording is of a mosque in Konjević Polje from Oct. 23, 1992, the day after it was shelled by the Serb army. In the video, we can see the damaged exterior and a pile of debris after the collapse of its pillars.

Five months earlier, tens of thousands of refugees from surrounding villages had poured into Srebrenica to escape the attacks of the Serb forces. Few could still imagine the catastrophe that would follow.

“Those days were very difficult for our people, so I filmed the refugees who blocked UNPROFOR (the U.N. peacekeeping force) asking them to protect us,” said Ibro, who filmed the arrival of French Gen. Philippe Morillon in Konjević Polje on March 6, 1993. However, the Serb army shelled the village from the nearby hills a few days later, killing and wounding many, so the people fled and UNPROFOR withdrew. “After that, we all had to go to Srebrenica.”

Ibro and his wife, Suvada, joined thousands of other refugees in Srebrenica, where they were welcomed by her family, who had already fled from the nearby village of Zalužje. Suvada was his only solace. “Because as far as filming was concerned, no one ever ordered or forbade me to do that,” he said. “I did it all on my own.” Sometimes Suvada filmed too.

By March 1993, the population in Srebrenica had grown from 9,000 to 42,000. As the enclave remained under assault, there wasn’t enough accommodation, medicine or food. The area was declared a U.N-protected zone at the end of April 1993, but the siege continued.

Two videos in Ibro’s playlist “Road to Žepa” show soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina passing through the region. The soldiers express gratitude for the hospitality as dozens of them eat the little food offered to them by the local Bosniak population. They sing songs “from future martyrs for future martyrs” while smiling.

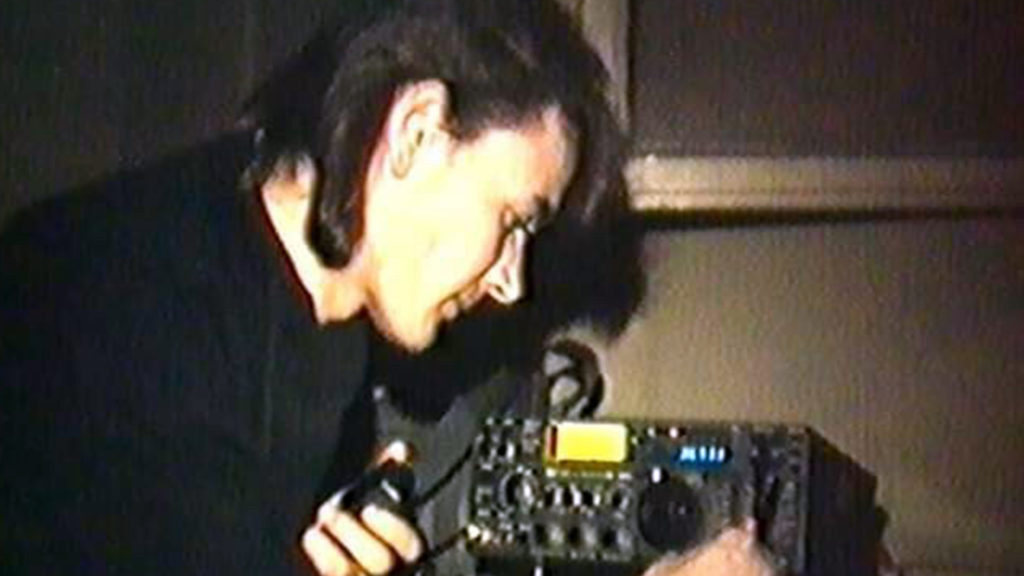

Ibro also started working in radio in July 1995, since it was the only way to communicate with the world from besieged Srebrenica, which was under a media blockade. On Ibro’s videos, we see groups of people lined up in front of his office, waiting their turn to try to get in touch with their relatives scattered around the world. Ibro praises twin brothers Sead and Senad Dautbasić, who organized a course for radio amateurs that Ibro attended. He started working in Srebrenica at radio club T91ESR, which had its premises behind the municipality building. The Dautbasić twins were killed in the genocide, their bodies later identified by their now late brother Adem, who also was a Srebrenica genocide survivor.

It was through radio also that journalist Nino Ćatić, who himself was later killed, sent a final message from Srebrenica on July 10, 1995, pleading for help:

“Srebrenica is turning into the largest slaughterhouse,” Ćatić reported. “The dead and wounded are constantly being dragged to the hospital. It is impossible to describe. Every second, three deadly missiles fall on this city. Now, 17 dead, 57 seriously and lightly wounded were brought to the hospital. Can anyone in the world come to see the tragedy that is happening to Srebrenica and its inhabitants? This is an unheard-of crime being committed against the Bosniak population of Srebrenica. The population in this city is disappearing.”

No one listened. And Bosnian Serb Ratko Mladić’s army was already at the town gates.

Ibro didn’t know Ćatić, who was sending reports for state TV from another building through a radio station that the Dautbasić twins were operating. Ibro was working with amateurs who were helping convey messages from the besieged people to their families. Other amateur radio team members included Halil Mehmedović, Ibrahim Bećirović, Nedžad Omerović, and Abid Zukić.

“It was done mostly at night for a better signal,” Ibro said. “I talked to my father in Germany on one occasion and to a professor from Bijeljina. I got in touch with many people from my homeplace who were then mostly in Switzerland. They asked me to record their own family members who were in Srebrenica and to somehow send the tape abroad. A couple of times it worked through UNPROFOR soldiers.”

Fourteen of those video messages from people in Srebrenica and surrounding villages are currently available on Ibro’s YouTube channel.

Ibro twice managed to send messages via videotape to his father. He continued filming the conditions in and around Srebrenica. In these videos, we see inhabited houses without windows, babies without shoes and worried faces of elders who tried to maintain hope about peace, but also smiles from those who felt seen by Ibro’s camera and mothers’ tears mixed with fake-cigarette smoke. Instead of coffee – which in Bosnian tradition is freshly brewed and served to a home visitor – we hear one host jokingly telling Ibro he could be offered only a fake coffee made out of lentils.

“I was without salt for a few days and ate oat bread and unsalted beans, and it went hard in my stomach,” Ibro said. “Some people went to Žepa to buy food from UNPROFOR soldiers and then brought it to Srebrenica and sold it at the market. There were people who had a lot of German marks, so they wanted to get rid of them, lest they were robbed or killed for the money. It was organized through us radio amateurs that someone in Srebrenica would give 1,000 German marks to me, and I’d tell my father to send someone he knows in Pula or Sarajevo 2,000 marks. So those people who had money doubled it and at the same time got rid of it.”

Ibro has three videos of a market in Srebrenica, from 1993, 1994 and 1995, showing high-priced, scarce items for sale, like cigarettes, flour, lighters, coffee and sugar, and other random products like calculators, pens, swim goggles and VHS cassettes. In one of the videos, Ibro holds several chocolate bars from a stand, joking, “Its date expired, 10 years, 10 German marks.”

Among Ibro’s other videos from Srebrenica are those of “Ljiljanijada,” sports competitions held in 1993 and 1994. Several people from surrounding municipalities participated. “In my recordings,” Ibro said, “the strongest man in Srebrenica was Šahbaz Musić from Kaldrmica, whom I recently met for the first time. He now lives in Berlin.”

In his footage, we can see men, women and children smiling at the camera, sending love, expressing longing for their relatives, with no certainty their messages would reach their recipients, and almost always adding, “If they can, may they send us help, but if they cannot, we still wish them all the best.”

Ibro didn’t have small cassettes, so he took out the tape from the big VHS cassettes and rewound the recorded material manually into a small cassett. He continued the tape by sticking one end to the other. After he would finish a new recording, he would put a small cassette back into the big one and wind the new tape in the small cassette. Ibro kept the large tapes in the apartment until July 10, 1995.

Mass executions started on the evening of July 11, 1995, in a former battery factory, then at a U.N. base in Potočari where thousands of refugees were located. From July 13 to 16, in the surrounding municipalities of Bratunac and Zvornik, organized killings took place at various locations.

By the time he left Srebrenica on July 11, Ibro had accumulated about 10 large VHS cassettes of recorded footage, and he was determined to get them out. So he decided to disassemble them one by one and rewind the tape by hand on one reel from the cassette. Finally, he got about 10 rolls of tape that he stacked on top of each other, then put them in a nylon bag and glued them with duct tape so that water could not damage the film. On the day of his departure from Srebrenica, he managed to make what turned out to be a historical recording during his last moments in town.

“It was hard for me to get out of the apartment on the fourth floor because the buildings were full of women and children who took refuge in the hallways because grenades were falling outside,” Ibro explained. “When I managed to get out, I was filming those scenes around UNPROFOR when women and children were climbing on trucks. It was horrible.”

Ibro’s publicly available videos show frightened, confused people and chaotic scenes around 2 p.m. on that hot afternoon, after a grenade fell nearby. By that point, the Serb forces were at the entrance to the upper part of the city. Ibro went back and told his wife that he would escape through the forest. He told his wife that she and their 9-month-old daughter should head to the Potočari UNPROFOR base.

“It wasn’t easy,” Ibro said, referring to saying goodbye to his wife. “But we didn’t feel too sad because we thought we would meet in Tuzla in a few days, and a better life awaited us. No one could have guessed what would happen and that so many people would be killed.”

Ibro, his father-in-law, and an 18-year-old cousin headed toward Kutlići, rushing to catch up with a column of people moving toward Buljim Hilj. He turned his camera on again at 2:37 p.m. and managed to record a few moments of shaken-up men, walking with nothing in their hands and just a backpack on their shoulders, before they heard the NATO planes. Around 2:40 p.m., two Dutch F-16 fighters dropped two bombs on Serb positions surrounding Srebrenica. But the Serbs threatened to kill their Dutch hostages and shell refugees in response, so further strikes were suspended.

Ibro’s camera battery was running low, and the heavy equipment was becoming a burden, so he thought of taking out the cassette and breaking the camera. He failed to remove the cassette so decided to keep the camera and carry it along. At nighttime, he met fellow radio amateur Nedžad, who offered to carry the camera for him. But they were soon separated in the melee. It took Nedžad seven days to reach free territory.

Ibro wandered for 36 days in the woods until in mid-August he reached free territory in Kladanj with a group of people from Žepa. An estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Bosniaks, 16 to 65 years old, had set off on that dangerous trek, which is now called the “Death March.”

Ibro recalled the fear and despair that was ever-present during his trek to the free territory: “I managed to get into the column of those people on July 12 around 11 a.m. That night was the worst time in my life. That’s the night I realized that their goal is to kill us all if they can. They called us with a megaphone and said that we were surrounded and should give ourselves up. My father-in-law suddenly decided to surrender, and I couldn’t convince him to continue with us. I knew the terrain because it was towards Konjević Polje, the place where I used to live. I told myself I had to survive. I didn’t want my child to be left without a father.

“I saw a dead man lying by the roadside, his body disintegrating in the heat. There was no one to bury him. I didn’t want to end up like that. I avoided the Chetniks as much as I could, so after nine days, I managed to get out of the area on the other side towards Hrnčići and reached the Udrč Mountain via Kušlat. I also came to the village of Glodi, where I spent the night and bathed in the river Drinjača. I didn’t know the terrain anymore, and the people I met there said that there were ambushes everywhere farther towards Tuzla.”

Among the retreating Bosniaks, about 7,000 to 8,000 were captured and killed by Serb forces. Some were tricked into surrendering, and other men committed suicide or died from dehydration and weakness. Only about 3,000 men survived. Ibro continued his march as the survivors dwindled in number:

“We returned to Udrč, and there we ate meat from an ox that our people stole from a Serb village near Cerska. That revived us, and we headed back to Srebrenica because I had a small radio, and I heard on Radio Sarajevo that the first people had already arrived in Tuzla and that Žepa was holding on and did not fall. After three or four days we managed to return to the same place from where we left for the village of Jaglice. Everything was deserted, night was falling, and we set off in search of food in the nearby houses. Ours was a group of 12 then. We ate all night, and I recharged the batteries for the radio. After two days, we came across the Crni Potok brook to the village of Poljanice, which then belonged to Žepa. There were already over 500 people from Srebrenica there, and we were well received by people from the village. After two or three days the Žepa town lines fell. Some people went across the Drina to Serbia to surrender there, and my group decided to hide in a canyon until the situation calmed down.”

Ibro was still listening to the news, but he would have to climb a rock to catch the signal. He heard of the famous “Storm” operation on Aug. 4-5, 1995, and when the town of Velika Kladuša in northwestern Bosnia was liberated. Ibro was coming out of that canyon to bring water and found a flock of sheep in the forest. “When I returned, I sent two men to bring us lambs to celebrate the news.” But much of that month was filled with uncertainty.

They stayed for about 10 days around those rocks until Ibro discovered a group of 28 men who were locals from nearby villages. “We agreed to go with them to Kladanj. The trip through the woods took six more days.”

Ibro reached free territory on Aug. 16, 1995, where he met with Bosnian army soldiers who gave them food and shared cigarettes. Ibro was transferred from Kladanj by bus to Ciljuge near Živinice. There was a military barracks, and he was taken straight to the kitchen to eat. That’s where he met one of his cousins, who told Ibro that she knew where his wife and daughter were and that they could be reached by phone through a woman from the neighborhood. Ibro’s wife, daughter and mother-in-law were already in Kladanj, transferred in a truck on the third day from Potočari alongside more than 20,000 other Bosniak women. Ibro’s father-in-law was killed after surrendering; his brother-in-law survived but was wounded and hospitalized.

Local military helped make the call and asked if Suvada could come to the phone. When she answered, the soldier broke the news of Ibro’s arrival to her. Suvada didn’t immediately believe that Ibro was safe and sound. Finally, after they had talked on the phone, Suvada paid a man to drive her to pick up Ibro. An hour later, she came with her uncle. When Ibro’s mother-in-law took his daughter, Arnela, out of the house to meet her dad, the baby girl recognized Ibro and spread her arms toward him. They settled in a cottage in Crno Blato near Tuzla.

Ibro soon discovered that Nedžad had survived and brought his camera too. “Nobody believed that I gave him a camera. It was rumored that I was killed and that Nedžad took the camera,” Ibro said. After a few days, Ibro located Nedžad’s phone number and contacted him, and they met in Tuzla. “He returned my camera, and I honored his help. However, he had given the tape to some journalists, and my recordings went around the world while I was struggling to survive. But later, Nedžad returned the tape that was in the camera to me.”

In 2010, Ibro started his YouTube channel with only a few recordings from Srebrenica. He explains that he did not want to publish them while the war crime trials in The Hague were going on. Ibro now invites people around the world who have saved videos to reach out to him so he can help digitize them for posterity. The Srebrenica Memorial Center is doing a major project of digitizing such footage too.

As Ibro went through his own archive, he came across footage that he thought he should post online because there are a lot of people in it who didn’t survive the genocide. As more people viewed it, Ibro started getting calls from all over the world. After he published a video about the young local singer Ibro Mujić, who was later killed, Mujić’s whole family called Ibro to thank him.

“His mother heard her son sing for the first time after 25 years,” Ibro said. “Also, the daughter of violinist Suad Mitić never saw her father or heard him play until I released the video. I was also contacted by a man from the U.S. who saw his brother playing the accordion for only two seconds. He asked me if I had a longer recording. He was willing to pay any price.” Ibro found a slightly longer recording and sent it to him for free. “Because such a thing doesn’t have a price,” Ibro said.

There are still a lot of videos that Ibro plans to publish on his YouTube channel. “What would be the point of all my work if I am the only one who watches those recordings?”

Ibro’s published videos and comments space has become a forum for precious online exchanges that remind people of old bonds and create powerful new connections among Bosniaks — of pain, love and solidarity.

In the comments section of Ibro’s videos on his YouTube channel, he gets many thank you notes from the diaspora and from within Bosnia and Herzegovina. They include comments from people who either still hope to find their relatives and friends in the videos that Ibro recorded or notes by survivors who talk about events from those years after recognizing a face or a place. Ibro’s published videos and comments space has become a forum for precious online exchanges that remind people of old bonds and create powerful new connections among Bosniaks — of pain, love and solidarity. They are also a potent proof against revisionist efforts of the genocide deniers, who sometimes post ugly comments on his videos.

Ibro now has a private business and still repairs TVs. He lives in Tuzla Canton and has his own house. “I often go to my hometown and sometimes to Srebrenica. I’m not interested in politics, but I’m sorry when someone denies what I survived and saw. Many of my war-surviving friends are scattered around the world, mostly in the U.S.”

He adds that he didn’t like watching his footage before but is now used to it. “Sometimes I like to watch just to remember.”