In June 2020, news photographer Kerem Gencer was an on-again, off-again student at Ohio State University in Columbus, the state capital. During the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests that summer, Gencer remembers police officers in riot gear lining the streets and cutting a menacing presence in public spaces, especially around the Statehouse downtown. Some protesters were roughed up, he said. Some were arrested. Many politicians, especially on the Democratic side of the aisle, were sympathetic to the movement.

Writing in the Black-focused newspaper the Los Angeles Sentinel on June 3, 2020, then-Sen. Kamala Harris of California said she was “proud to stand with protestors” and was “heartened by how many people — from all races, ethnicities, and walks of life — joined our rallying cry that enough is enough.”

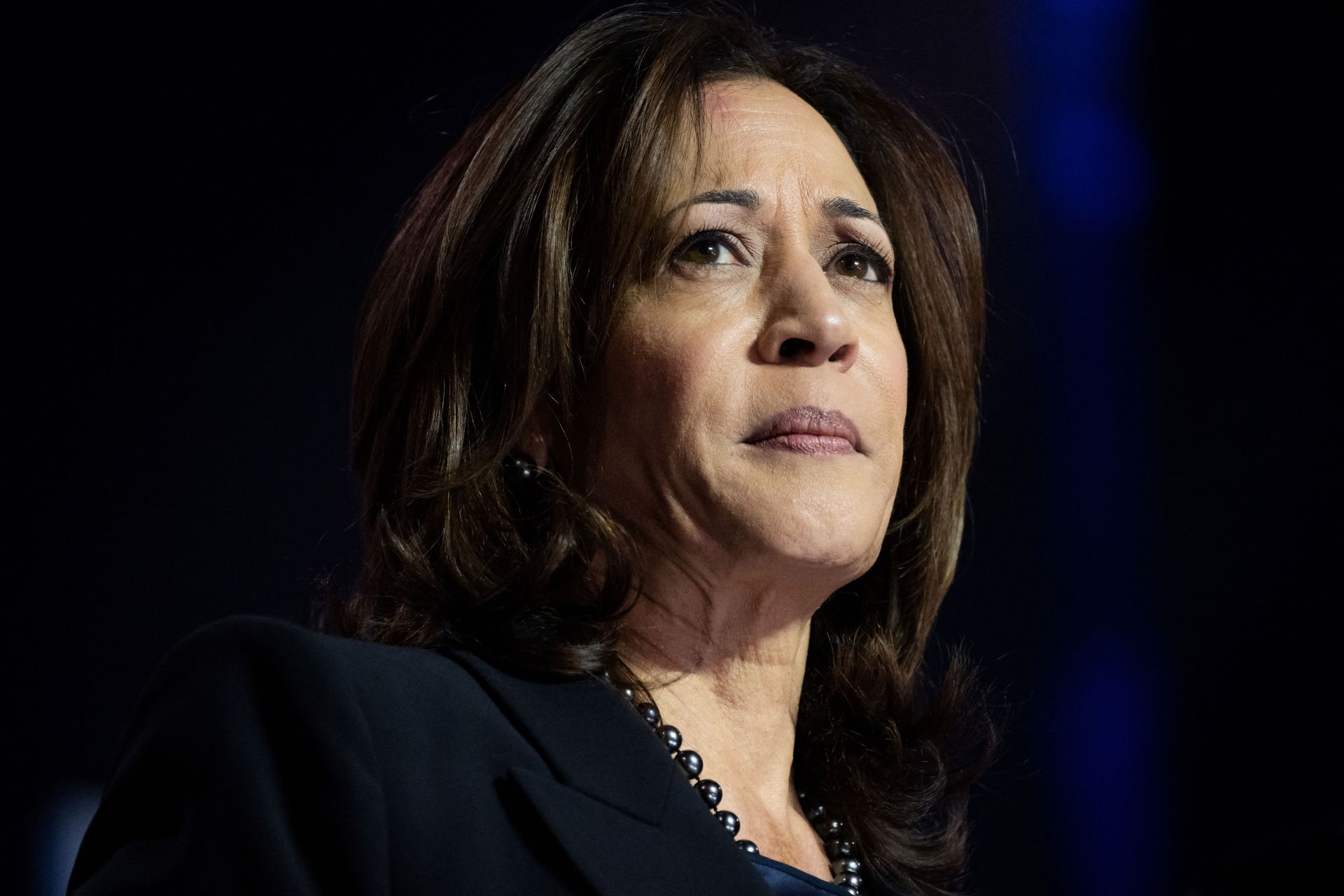

Fast forward to 2024, and Harris, now the Democrats’ presidential nominee, is sounding a different tune when it comes to the ongoing protest movement against Israel’s assault on Gaza.

Gencer should know. When I met him last week, he had just returned from Washington, D.C., where he covered the July 24 rally against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s address to Congress. He showed me images of fellow photographers struggling to open their eyes after being assaulted with pepper spray, and he remembers all too well what Harris had to say about the events. The next day in reacting to the rally, which reiterated calls for a Gaza cease-fire — a sentiment the overwhelming majority of Democrats share — Harris seized on isolated incidents in a statement that, except for one sentence on “the right to peacefully protest,” is entirely about “unpatriotic protesters” whom she accused of “associating with the brutal terrorist organization Hamas.”

“For a presidential candidate who wasn’t nominated through a democratic primary process, I’m not all that surprised that Kamala conflates the expressed voice of the American people with unpatriotic protest,” Gencer told me.

Analysts have looked for signs that Harris can win over progressive voters angered by President Joe Biden’s support for Israel’s war in Gaza, the death toll from which hovers around 40,000 Palestinians, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (a July 5 report in The Lancet argues that that number may be as high as 186,000). Although a much-touted Aug. 10 New York Times poll showed Harris pulling ahead of Republican rival Donald Trump in key swing states, interviews by New Lines suggest that many progressives are far from extending her the kind of exuberant support coming from the Democratic mainstream, which has wasted no time embracing the candidate and her “Midwestern dad” running mate, Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota.

Of course, it would be a mistake to reserve blame for that lukewarm response to voters of Arab or Muslim descent, as the legions of Jewish-American activists packing Congress and New York City’s Penn Station to protest Israel’s policies could attest. Even the BLM movement Harris claimed to champion in 2020 raised questions about her nomination, citing the undemocratic process that catapulted her to the top of the Democratic ticket and calling on the Democratic National Committee (DNC) to “host an informal, virtual snap primary across the country prior to the DNC convention in August” to allow “for public participation in the nomination process, not just a nomination by party delegates.” (BLM’s request went unheeded; the convention begins today in Chicago.)

Still, some in the party have tried to paint Arab- and Muslim-American voters as spoilers, intent on making Gaza their “single issue” ahead of the November vote. Writing on the social platform X on July 23, Abbas Alawieh, a Michigan activist and Democratic delegate, recounted another delegate telling him, “Shut up, asshole,” while on a DNC call in which Alawieh urged participants to “adopt a more humane Gaza policy.”

Less crass but no less dismissive was Harris’ Aug. 7 reaction to protesters just outside Dearborn, Michigan, home to the largest concentration of Arab-Americans in the country: “You know what, if you want Donald Trump to win, then say that,” Harris admonished the group in response to their chants, which included “we won’t vote for genocide.” Just two days later, no doubt aware of the backlash her rebuke had caused, Harris softened her tone with protesters in Arizona, telling them, “I respect your voices” and “now is the time to get a cease-fire deal.” For many observers, though, Harris is a long way from winning over skeptics of her Gaza stance.

Those skeptics include more than half-a-million Democratic voters who cast “uncommitted” ballots in the presidential primary rather than support Biden. The protest vote, which was larger than Biden’s winning margin in 2020 in some battleground states, including Michigan, was intended to send a message to the president that his reelection was at stake if he refused to change course on Gaza. But the goal of uncommitted voters was always to force that change, ending the administration’s near-total diplomatic and military support of Israel, not to abandon Biden altogether.

As Layla Elabed, one of the organizers of the uncommitted movement, told New Lines in May: “We are saying to Biden, there is time between now and November for you to listen to your constituency — not only the hundreds of thousands who have cast protest votes across the country, but also the majority of Democrats who oppose Israel’s actions in Gaza.”

With Biden now out of the race, the uncommitted movement has projected cautious optimism about Harris’ willingness to break with the president’s track record on Gaza. In a statement after Harris tapped Walz as her running mate, passing over Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro — who compared antiwar protesters to the Ku Klux Klan — Elianne Farhat, a senior adviser to the uncommitted movement, said that the vice presidential nominee had “demonstrated a remarkable ability to evolve as a public leader” and that he had an opportunity to unite the party “by supporting an arms embargo on Israel’s war.” Part of Walz’s appeal is that he has expressed some sympathy for the protesters’ position, calling Minnesota’s 45,000 Democratic primary voters who opted for the uncommitted line “civically engaged.” That number earned the uncommitted slate 11 delegate spots for the DNC, one of them filled by activist Asma Mohammed, who told Politico that “while Walz is a great pick, he’s not going to push [Harris] over the edge.”

“If we do not have a cease-fire and arms embargo promise from Vice President Harris, come November, I am sure that we will lose,” she told the political news outlet.

A recent YouGov/IMEU Policy Project poll showed that among “undecided” voters, 57% in Arizona, 44% in Pennsylvania and 34% in Georgia — all swing states — would vote for the Harris-Walz ticket if the candidates pledged to withhold weapons to Israel. For Eman Abdelhadi, a sociologist at the University of Chicago, securing that commitment should be a prerequisite for endorsing Harris. “Otherwise,” she says, the candidate’s policy on Gaza “would basically be Biden 2.0.”

Abdelhadi, who voted “uncommitted” in the Illinois Democratic primary, says she is listening for “more than a change in tone” from Harris before she commits to voting for her. At the same time, she is keenly aware of the stakes for vulnerable groups in the upcoming election.

“If Trump wins, progressives will be busy putting out fires on a daily basis instead of focusing on the long-term change we want — for Palestinians and for other vulnerable groups,” she says. In that sense, she agrees with Democrats that Trump is a threat to democracy. “But if democracy really is on the line,” she adds, “then why risk it for an Israeli government whose assault on Gaza most Americans oppose?”

Abdelhadi acknowledges that some progressives are unlikely to support Harris even if the vice president were to commit to an arms embargo, which many would see as an empty campaign promise. Although Abdelhadi may ultimately decide to vote for the Democratic ticket, she says that, as a leader in her community, she “won’t be doing the work of campaigning” for Harris if the candidate “doesn’t give voters what they are demanding.”

Despite recent polls conducted by The New York Times and Siena College showing Harris and Walz with a narrow lead over Trump and J.D. Vance in Michigan — where more than 100,000 Democrats cast uncommitted votes in the presidential primary — some activists say that the numbers don’t fully capture the extent of voter dismay with the vice president, who, they say, has not done enough to distinguish herself from Biden on Gaza.

In late July, the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee surveyed its membership of more than 40,000. Harris polled at only 27.5%, while Green Party nominee Dr. Jill Stein — who has called Israel’s actions in Gaza a genocide and recently approached high-profile Palestinian activist Noura Erakat as a potential running mate — had 45.3%. The results showed Harris faring only slightly better than Biden when he was the presumptive nominee.

In a study it published shortly before Biden dropped out of the race, the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, in partnership with Change Research and Emgage Foundation, showed that only 12% of Muslim voters in the three swing states of Georgia, Pennsylvania and Michigan intended to vote for Biden, down from 65% in 2020.

For Jacob Saliba, executive director of the Arab American Voter Project, even those numbers might not tell the full story. In May, Saliba told New Lines that Arab-American “civic participation is demanded at this moment, and we will not be silent.” Now that it’s clear neither political party is “willing to enforce red lines” on Israel’s actions in Gaza — from daily massacres to enforced starvation — he sees a different trend within the community.

“For many, just talking about voting in the next election is almost a taboo subject,” he told me. “The first assumption is that neither of the candidates cares about us or about the suffering in Gaza.”

That may mean fewer opponents of Israel’s war are responding to polls ahead of the election. It may also mean that some who intend to vote for Harris are “ashamed” to say so, Saliba said. Still others have told him privately that they intend to vote for Trump, believing that the former president would have “somehow reined in” Israel’s actions. “People are saying, ‘We don’t care that he moved the [U.S.] embassy to Jerusalem, we don’t care that he insulted Palestinians at the debate — we just want the massacres to stop.’”

Some voters are so put off by the scale of the slaughter in Gaza that they are committed to not voting at all. Saliba, who in March helped organize a packed town hall in Cleveland for the Arab-American community to meet local candidates, says his group is struggling to attract interest from eligible voters now.

“Just the word ‘voter’ in our name means people don’t want to pay attention,” he tells me, adding that, after 10 months of what international legal observers have called a genocide, many in the community see unqualified U.S. support for Israel’s actions as a denial of Palestinians’ basic humanity. “They are saying, unless [Harris] gives us concrete commitments that [her administration] would not give any aid to Israel, our humanity is not being seen.”

So far, Harris has fallen well short of that standard. On Aug. 8, the vice president’s national security adviser, Philip Gordon, reiterated that she does not support an arms embargo against Israel. On Aug. 9, Harris stayed mum when the State Department approved an additional $3.5 billion in supplemental aid to Israel, including cash to purchase more U.S. weapons. The department’s announcement was condemned by the organization Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN), which issued a statement citing “extensive evidence documenting the Israel Defense Force’s use of U.S. weapons to carry out war crimes and crimes against humanity.”

Democratic insiders who have been pressing the party to shift its Israel policy remain hopeful that a Harris White House might push back on military aid in particular. But they are not pinning all their hopes on the next administration, either.

“For change to happen, we must think long term, not one election cycle,” says Iman Jodeh, the first Palestinian American and Muslim to hold a seat in the Colorado state legislature. Though uncommitted voters cast nearly 10% of Democratic primary ballots earlier this year, Jodeh, who also spoke with New Lines in May, believes that the number “is not fully representative” of Americans for whom Gaza is top of mind in the upcoming presidential election.

“One thing I’ve noticed in all of these rallies [for Gaza] is that the majority of people who show up are, in fact, not Palestinian and not Arab,” Jodeh adds. “What we all have in common is that we fight oppression in all its forms. We sought to secure civil rights, affirmed Black Lives Matter and ensured women’s equality, and now we stand against genocide and demand a change in U.S. policy” toward Israel.

Hussam Ayloush, an elected delegate and past executive board member of the California Democratic Party, acknowledges that Harris has taken “baby steps” toward challenging Biden’s unquestioning support for Israel. He notes that she sat out Netanyahu’s address to Congress (a move that her campaign chalked up to a scheduling conflict); that her remarks after meeting Netanyahu highlighted Palestinians’ suffering and right to freedom and self-determination; and that her choice of Walz over Shapiro signaled her willingness to forgo a staunchly pro-Israel candidate, even if it risked accusations of “caving” to antiwar protesters.

“I don’t think these steps have sealed the deal for her” among opponents of Israel’s assault, Ayloush cautions. “But many are noticing that there is an attempt to distance herself from Joe Biden [on Gaza], something that will not be easy for her as Biden’s vice president.”

Still, Ayloush warns that Harris will need to articulate “commitments of substance” if she hopes to win over disaffected Democratic voters. Like others, he believes those commitments need to include a vow to stop the flow of deadly weapons to Israel and end “diplomatic cover on the world stage” for Israeli actions. If Harris wins in November, Ayloush says he and others in the Democratic Party intend to hold her accountable on these commitments, including by paying close attention to “who she hires to oversee American policy on Israel.”

In his roles as CEO of the Council on American-Islamic Relations in California and executive director of its Greater Los Angeles office, Ayloush has also noticed a growing level of dissatisfaction and frustration among Muslim-American voters.

“They are losing confidence in both main parties’ ability or willingness to challenge Israel on the current genocide in Gaza,” he said.

As Democrats were preparing to get the convention underway, activists amassed in Chicago, reiterating their calls for the U.S. to immediately end military aid to Israel. In an Aug. 10 Instagram post, the Palestinian Youth Movement said it was joining a broad coalition to protest the Biden-Harris administration’s “unconditional diplomatic and material support to Israel as it commits a genocide against the Palestinian people.” The post goes on to reference the nationwide student encampments that drew unprecedented attention to the Gaza protest movement during the spring.

Even if Harris as nominee were to signal a more balanced policy toward the Palestinians, as president she would likely face staunch opposition from Congress, which has made no secret of its disdain for the unyielding protest movement. From pushing the resignations of the Harvard and University of Pennsylvania presidents over accusations of antisemitism to vilifying peaceful student encampments on those campuses and around the country, the same U.S. legislators who gave Netanyahu standing ovations on July 24 are unlikely to side with opponents of Israel’s war, even if the latter might earn the passing sympathy of a prospective president.

One look at Gencer’s photos from that day leaves little doubt what’s at stake for progressives who want to see an end to Gaza’s suffering. It’s also a good indication of just how hollow the Harris campaign’s pitch has sounded to them so far.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.