The bold black “M” for male on Alexandra’s ID card was more than a relic of a past life. It was the final barrier to full societal acceptance. The fear of being outed was constant. When she visited the doctor, would they call out “Mister” in front of everyone, as they had done before? At a hotel, would the receptionist do a double take?

“I didn’t want to live a life registered by the state as a man when I look the way I look, and society treats me as a woman anyway,” Alexandra, who only gave her first name, told New Lines. The only escape was to change the male identifier on her documents through legal gender recognition. And in Czechia (more widely known in English as the Czech Republic), where Alexandra is from, that meant being compulsorily sterilized.

By the time Alexandra turned 22, in 2022, she had been taking the testosterone blocker Androcur for years. She had decided against surgery — it felt too risky, too onerous. She believed the drugs already likely made her infertile. But the Czech 2012 legal act governing the process was exacting: Transgender people were defined as those who had “surgery while disabling reproductive function.” To comply, Alexandra reluctantly underwent major surgery in 2022. The orchiectomy, a 30-minute, generally low-risk procedure that removes one’s testicles, went well. But as the days went by, the pain didn’t fade; it grew stronger.

One week on, dozing at home in Pilsen, she woke up in agony, surrounded by blood. She had developed an infection. “The wound had burst. There were pieces of hematoma and pus around me,” Alexandra recalled. She rushed back to hospital, where she said staff began probing her with no anesthetic. “It was the worst pain of my life.” She spent two months recovering, bedridden for weeks.

Alexandra may have been unlucky to fall ill. But the bureaucracy that pushed her to the operating table wasn’t unique. For decades, legally changing your gender in much of Europe required invasive procedures or hormones that left you sterile, regardless of whether you wanted them.

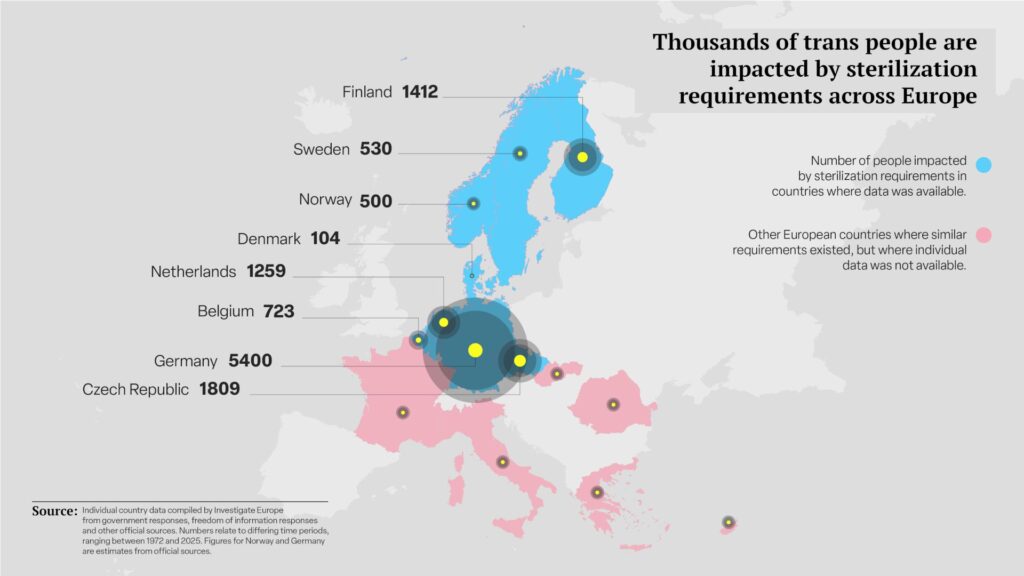

At least 11,000 people across six European Union countries were subjected to compulsory sterilization or similar procedures as a prerequisite for legal gender recognition between 1972 and 2025, an investigation by New Lines and Investigate Europe reveals. This first cross-border figure is based on previously unreported official figures from Belgium, Czechia, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, where sterility was long an explicit prerequisite for gender recognition, considered the price one had to pay.

The mere possibility, however unlikely, of trans men carrying children or trans women having them was seen as too disruptive for society to accept. Better, it seemed, to eliminate the chance entirely — at least for those seeking legal recognition from the state.

Although most European countries have now removed infertility as a legal requirement for gender recognition, few have acknowledged the harm these policies caused. To date, only two governments, Sweden and the Netherlands, have offered reparations, and only after sustained pressure from activists.

Legal gender recognition is technically voluntary, but life without it can be untenable. From health care to housing, job-seeking, freedom of movement and residency rights, documentation does matter.

“I didn’t make the decision because I wanted to. I needed to,” Alexandra explained. “It was a question of having the same rights, essentially, as other women around me.”

Rights groups have long criticized the policy. Sterilization requirements have forced trans people to “decide between two of their own human rights — the right to bodily integrity or freedom from unwanted medical interventions, and the right to privacy or recognition before the law,” said Cianán Russell of LGBTQ+ advocacy group ILGA-Europe.

“If one must ‘choose’ to be subjected to a medical procedure to be able to live safely and freely — for example, to open a bank account or apply for a job — then the medical procedure isn’t a choice at all,” Russell stressed.

It is impossible to know how each person granted legal gender recognition under such conditions felt. Many trans people actively seek to change their bodies in ways that will certainly or probably leave them infertile. Some choose to first preserve gametes — eggs or sperm — to use later in assisted fertility.

New Lines and Investigate Europe spoke to more than a dozen people with stories like Alexandra’s. At least three of those interviewed said they were not properly informed about the possibility of preserving gametes beforehand and later realized, with great sadness, that they had restricted their parenthood options. Several suffered serious health complications; one even developed a rectocele following their hysterectomy, a form of pelvic organ prolapse.

Others were simply angry, haunted by the question of why the state insisted that their bodies be so radically altered as to rule out procreation, and the injustice left for the most part unacknowledged.

A quarter century after her recognition by the German state as a woman, Cathrin Ramelow still feels she was denied certain possibilities, like the chance to preserve sperm preoperatively, or simply the option of not having sterilizing surgery. “I feel cheated out of options, that in none of the many mandatory consultations was I told that there were other options from a purely medical point of view,” she said.

For many transgender people, surgeries such as vaginoplasty or phalloplasty — which can involve the removal of testes or ovaries (gonadectomies) and the construction or removal of genitalia — are a much-desired part of physical transition. Hormone treatments used to modify one’s voice, body hair and the presence of breasts also come with fertility loss. Generations of trans people have fought to safely and affordably access such treatment, a battle that is still ongoing.

But a significant minority, like Alexandra, do not want so-called bottom surgery to restructure their genitals, or only want a limited form. Such procedures are expensive, invasive and come with lifelong impacts. A major U.S. survey conducted by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and the National Center for Transgender Equality in 2011 suggested that 21% of trans men had no desire for a hysterectomy and 14% of trans women did not want an orchiectomy. Nonbinary people, who feel neither strictly male nor female, report being even less interested.

The removal of Italian trans rights activist Christian Cristalli’s uterus had nothing to do with his own vision for his body and everything to do with conditions imposed by Italian judges. “I had top surgery — a mastectomy — willingly, because I wanted it,” he said. “I wanted to change my body in a way that made me feel good.”

“The removal of my uterus and ovaries wasn’t part of my personal path. I was forced to undergo it in order to be granted documents with my new name,” the 37-year-old explained. “If the first operation brought me joy and liberation, the second remains an open wound.”

He tried desperately to avoid it, petitioning local officials in his city of Bologna with a photo of himself with a mustache and beard. He would have even accepted keeping the female “F” marker on his ID card, he said, but as graduation approached, he saw no other way to ensure the name “Christian” was used on his diploma. His birth name would have outed him as trans to his entire social circle and any future employer.

Cristalli feels he and others were forced into sterilization. Two years after his procedure, Italy’s Constitutional Court struck down surgery requirements. “It was a state-imposed act meant to reassure the system that I could never father children, to preserve the so-called natural order.”

Elected officials in Belgium, Czechia, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden explicitly wrote sterility and infertility requirements into the laws of their countries. The first was introduced in Sweden in 1972, and stayed in place for 40 years. The last to go, the one in Czechia affecting Alexandra, was only phased out at the end of June this year — three years too late for her.

The data for this investigation was gathered over six months from ministries, hospital and court records, and academic studies obtained in part through freedom of information requests. It hints at the broad reach of a policy that was repeatedly condemned by United Nations experts and the European Court of Human Rights, but long remained a reality.

In practice, across much of Europe, this has often meant undergoing at least a gonadectomy, a term that covers both hysterectomies and orchiectomies. The true number of people affected by these practices to access legal gender recognition, now widely accepted as a right in most EU countries, could be much higher than 11,000.

The Slovakian Health Ministry imposed official guidance to the same effect, and in Norway and Denmark it was de facto policy too. In other countries — Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy and Romania — judges demanded proof of surgical intervention likely, if not certain, to leave one sterile. Reliable data was only available for the six countries used for the estimate, and even then was in some respects incomplete.

The first infertility clauses in Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany dated back to the 1970s and ’80s and were justified in terms of family law. The logic was that a child must have a father who was a legal man and a mother who was a legal woman, according to legal scholar Peter Dunne. Anything else would unleash chaos and possibly present child protection concerns. In the decades that followed, other countries followed suit and adopted similar policies, often without questioning whether they were truly necessary.

Joz Motmans of Ghent University Hospital’s Center for Sexology and Gender believes Belgium’s 2007 law stemmed from misguided binary thinking rather than malice. “The whole idea of what they called transsexualism was that a person was born in the wrong body,” the psychologist explained. “That was what medical practitioners did: They helped the person to correct the body.” Those “corrections” were perceived to mean inevitably giving up your chance to have children.

Motmans, who is himself trans, witnessed the legislation’s birth firsthand some 20 years ago, sitting in on sessions in the Belgian Parliament as a doctoral student. He still recalls his shock at the proposal that applicants should be “no longer able to conceive children in conformity with their previous sex.”

One Belgian lawmaker, when challenged by activists, exposed a lingering fear of trans procreation. “You could get into a situation where a man could bear a child and a woman could sire one,” Hilde Vautmans, a center-right politician who helped spearhead the law, said at the time.

Despite protest — some said it smacked of eugenics — the clause remained. From 2007 until 2017, when Belgium changed its laws, more than 700 people were subject to infertility requirements, according to figures from the Ministry of Justice that were shared with Investigate Europe. Vautmans told us the law had been “groundbreaking” at the time, but acknowledged such conditions no longer reflected ideas of equality. “The sterility requirement was then seen as the only politically feasible way forward, even if it was restrictive,” she said.

Belgium was among the last countries to introduce such a condition. From 2010, similar ones were gradually struck down in national courts in Germany, Greece, Italy and beyond.

The Strasbourg-headquartered European Court of Human Rights also condemned several states, including France, Romania and Italy. In 2017, judges in the French city found for the first time that such requirements violated trans people’s right to private life, under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Until 2016, French judges required surgery or hormone treatment so extensive that individuals were likely left infertile, even if sterilization wasn’t legally mandated.

From 2018, Sweden granted 530 people around $24,000 each in reparations. Starting in 2020, the Netherlands awarded 1,259 people around $6,000 each. In an official apology, two Dutch ministers called the 1985-2014 law a “violation of bodily autonomy that would be hard to imagine today.”

Germany, where court records and official figures suggest that more than 5,000 were subject to sterility conditions between 1980 and 2011, has been pondering compensation for years, but nothing has materialized. “Discussions on the possibilities of recognizing the suffering and injustice suffered by transgender and intersex people have not yet been completed,” said a Ministry of Families spokesperson.

Norway introduced legal gender recognition reform in 2016, but stopped short of offering compensation. “There is an incredible lack of willingness to acknowledge the blatant human rights violation against a minority group committed by the state,” said Aleksander Sørlie, a 33-year-old trans man from Norway who had a hysterectomy in 2014.

The government argued that doing so could set a precedent for other groups seeking redress for historical injustices. Bent Høie, the former Health Minister who helped spearhead the reform, said it would be difficult to push it through today. “We see that there is a completely different mood,” he explained, with politicians exploiting gender debates to their political advantage. “Trans people become symbols of everything that is going wrong.”

In the past decade, many countries moved to less restrictive models of legal gender recognition. Belgium, Germany, Greece, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal and Spain now use self-identification, allowing people to change their official gender with a simple declaration rather than proof of surgery or psychiatric diagnosis.

While sterility requirements have been dropped in most of Europe, advocacy group Transgender Europe claims that 12 EU countries still impose what they term “abusive medical requirements,” such as mandatory mental health condition diagnosis, surgery or hormone treatment.

At the same time, activists warn of dangerous backsliding in some places. In May, the organization reported that transgender rights regressed more than they advanced across 54 European countries for the first time in a decade.

There’s a sense that hard-won gains rest on fragile ground. Many look to the U.S., where President Donald Trump devoted some of his first hours in office to issuing executive orders calling, among other things, for trans women to be moved to male prisons.

Hungary’s conservative Prime Minister Viktor Orbán already spent years rolling back LGBTQ+ rights, often citing “child protection.” In 2020, legal gender recognition — previously possible — was banned entirely, with or without surgery. “The issue of sterilization is not really relevant; the problem is much more serious,” said Tamás Dombos of the Hatter Society, an LGBTQ+ advocacy group.

In Slovakia, efforts to end sterilization backfired. In early 2023, the outgoing health minister issued new guidelines expunging a reference to the practice. But six months later, under a new government led by populist Robert Fico, the reform was retracted. No alternative followed, and as in Hungary and Bulgaria, legal recognition has stalled.

Czech activists, who fought for years to overturn the clause, still fear a gray zone. The Constitutional Court condemned it last year, instructing the government to replace it. So far, no proposal has materialized. ILGA now expects the system to hinge on ministerial guidance, which it sees as flimsy and vulnerable to rewriting by future governments. “Trans people in Czechia will be left in legal limbo, without access to a safe, dignified, and timely process,” the campaign group warned in June.

Alexandra said she is “genuinely happy” that her country has changed its system, even if the change came too late for her and it is unclear how things will work.

When her revised papers came through a month after her operation, she didn’t feel joy, just pain. Three years on, the anger is still with her. “I am bitter, and rightfully so. … I went through all of this trouble for something that should have been mine already.”

In Italy, Cristalli has also not forgotten. “Our desire to exist outside the norm frightened people. The idea of a trans person becoming a parent, loving, raising and creating life, shattered an entire ideological structure. And I keep talking about this violence because it must never happen again. To anyone.”

Additional reporting: Lorenzo Buzzoni, Paula Zwolenski, Martin Vrba, Pascal Hansens, Eurydice Bersi, Leïla Miñano, Amund Trellevik and Matúš Zdút

New Lines is the exclusive English-language partner in this project, led and coordinated by Investigate Europe, a cross-border team of investigative journalists. The investigation is being published with media partners in 10 countries: France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Norway, Romania, Slovakia and the United States.

IJ4EU (Investigative Journalism for Europe) provided funding support for the investigation.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.