In Jaffa, what started in recent weeks as protests against Israel’s housing policies has now grown in solidarity with Gaza and Sheikh Jarrah.

Like their brethren in East Jerusalem, the Palestinians of Jaffa have been facing evictions. Also like in Jerusalem, the police responded to protests with violence and fired stun grenades indiscriminately. Armed reinforcements arrived in advance, along with Friesian horses, imported from abroad for protest dispersal. The beasts stand menacingly over a crowd and leave a trail of manure wherever they go.

Even before the violence in Jerusalem, sentiments in Jaffa had already surpassed a simmer. In April, residents protested the sale of a building to a yeshiva seminary, part of what Palestinians see as a systematic, state-sponsored dispossession of what remains theirs in Jaffa. They shouted, “barra barra mustawtinin” (out, out, settlers). But this was not taking place on the winding matrix of roads that connect Israel’s gated settler communities in the occupied West Bank: This was unfolding in the heart of Jaffa. Once Palestine’s most populous city, today it is an appendage to Israel’s commercial capital, Tel Aviv.

The protests continued and the yeshiva’s rabbi was attacked. Local councilman, Chaim Goren, vowed to strengthen Jewish presence in the area, and the beleaguered Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called for the “swift arrest” of the perpetrators. Netanyahu’s erstwhile ally Naftali Bennett, who harbors his own aspirations for the premiership, dubbed the attack an “antisemitic hate crime” in his one-upmanship.

Despite the furor in the media, the indictment filed at Tel Aviv Magistrate’s Court against brothers Ahmed and Mahmoud Garbua asserted that the assaults on the Rabbi of Shirat Moshe Hesder Yeshiva, Eliyahu Mali, and Moshe Shandovitz, the manager of the yeshiva, were not racially motivated. Shandovitz was keen to play down concerns of escalation: “Peace has already returned to Jaffa,” he told New Lines.

But peace has long been precarious in Jaffa. Demonstrations over this issue had been simmering since the new year, when a handful of local homes were put out to tender by the state-owned housing company, while Palestinian tenants still lived in them.

Yara Gharablé, a 24-year-old protest organizer, explains that you can’t understand the problems in the city without its “proper political and historical context — the Nakba.” In the case of Jaffa, 95% of the Palestinian population, exceeding 100,000 people, were displaced. But for the Palestinians who had the fortune to stay, there was extreme alienation.

Those who remained had to reorientate themselves in an entirely different city. The local nickname of the city — um el-gharib, meaning “mother of the stranger” — took on a piercing new connotation. The streets, emptied of their neighbors, were renamed after Jewish and Zionist figures; entire neighborhoods, such as Abu Kabir and the preeminent Manshiyya, were razed. In the latter, the last remaining stone building has since been renovated into a beachside homage to the Zionist paramilitary group, Etzel, responsible for the “liberation of Jaffa.”

The coastal neighborhood is now buried under Charles Clore Park, an early frontier of southward development from Tel Aviv. Today, it is filled with grandmothers on deckchairs, morning yogis, and tangled-haired surfers making their way into the frothing sea. There is no trace of the world left behind under the towering blue and white flags overlooking the beaches.

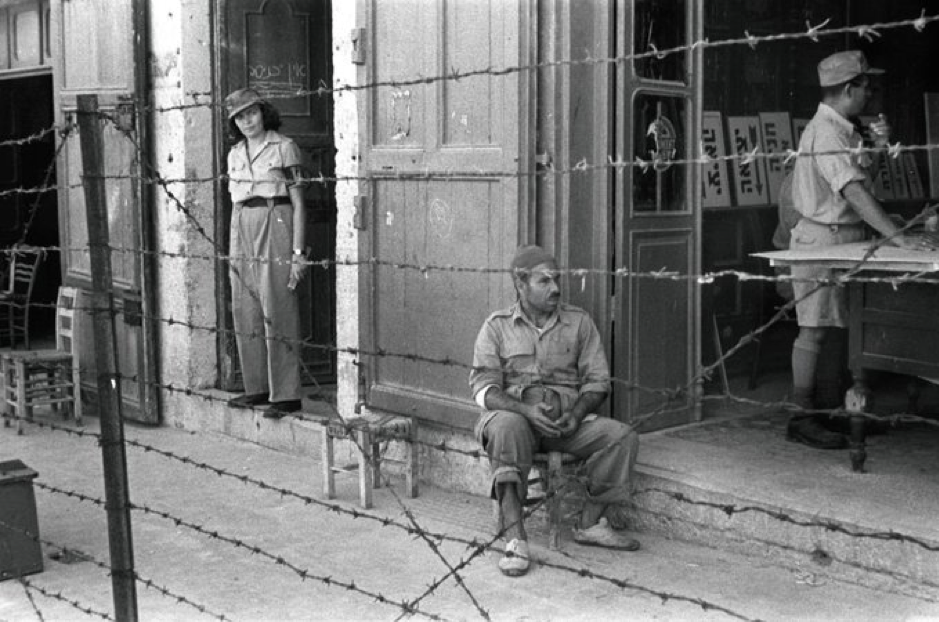

Following the mass exodus of Palestinians, those who remained were corralled and concentrated into a single neighborhood, Ajami, referred to as the “ghetto” by Jews and Palestinians at the time, and placed under martial law for a year. Their property was handed over to immigrant Jewish families, and to other Palestinian families. Not only was the city reengineered, but the airy, Oriental buildings expropriated from the locals were also quartered into smaller units.

To leave the ghetto, Palestinians had to sign papers in a foreign language and pay a third of the value of the property in exchange for a discounted rate of rent and the status of “protected tenants.” This strange limbo status concocted by Israel means they could face eviction if they breached the draconian clauses of their contract: they are forbidden from building or occupying empty sections of a building, and critically, the home can only be passed down “one generation.” This means that the era of protected tenancy, which applies to around 40% of the Palestinian population in Jaffa, is reaching an endpoint. This is how Palestinians became “squatters” (the term used by the Israel Land Authority) not only in their own land, but in their own homes.

The genealogy between the dispossession of Palestinians in 1948 and the contemporary housing situation is clear. Following Israel’s passage of the Absentee Property Law in 1950, which legalized state seizure of homes of Palestinian refugees, the management of the properties was transferred to Amidar, a state-run public housing organization. This same organization is threatening to evict the residents of Jaffa in 2021.

Although the overwhelming number of the 1,200 homes under their management in Jaffa are inhabited by Arabs, Amidar’s website, unlike all other government services, has no Arabic-language option and boasts of “70 years of Zionist activity.”

Their responses to press requests insist they treat their clients equally and invokes the option for discounted purchases for families, but testimonies from families attest to a convoluted process that seems designed to trip them up: a salvo of fees, sprawling administration, appraisers, and lawyers, the cost of which falls on the families, most of it is nonrefundable. Over the course of the long-winded process, the market is driving up property values.

Rawdah Abu Khater, however, wasn’t even offered the chance to buy. At a protest against her treatment, her soft eyes are crinkled, somewhere between pride at how many have come to support her and the grief of imminent eviction. “I’ve aged 10 years from the stress,” she tells the crowd, who gathered toward the end of the day’s fast. But when Ramadan ends, she is set to be evicted from her home. The matriarch of a house of seven, she survived an abusive marriage and cancer, but she lost the battle to stay in her home and her house went up for a closed auction in 2018.

In late April, Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality opened registration for a housing lottery for Jaffa’s “Arab, Christian, and Muslim residents” to purchase 28 subsidized apartments in Jaffa at 30% of the market price. They also approved a further public housing renewal program in Ajami. At the protest outside Rawdah’s home, a leader of the burgeoning movement, Ahmed Mashharawi, slammed the project: They have been working on it for 12 years, he said, and they should be ashamed for framing it as a new initiative. For perspective, 1,400 units in the area are slated to be built on Rawdah’s home, and “we all know how many Arabs will be allowed to live there.”

The Al-Khaters are just one of hundreds of families with an eviction notice looming over their heads. The Copty family home, on the other side of Jaffa, has stickers on their metallic door warning about their German shepherd, but Joy rubs against your feet upon entering. A visibly distressed Aznif Copty says that Amidar “never stretched out their hand to try and understand our situation.” A wooden cross hangs on the wall of their single-story home, which is located near Amidar’s local office in the heart of Ajami. Like many other families, they are protected tenants, but were issued an eviction notice out of the blue.

Amidar did not respond to questions about the issue.

As part of a legal compromise reached in 2013, Amidar gave them the option to buy their home at a discounted price, but only after they signed the agreement did they discover the fragmented legal status of their home: There is a requisition order on half the house from the municipality to build a road that has already been built, while another chunk of the home has no legal owner, making it impossible to acquire a mortgage. The terms also force them to buy the building rights, not just their home: Her husband, Kamil, acerbically refers to this as “the air above their houses.”

Kamil was born in this house, after his family were expelled from another house a stone’s throw away. He is tired and direct: “We want to buy our home, but they do everything to try to trip us up. Our case is proof that Amidar doesn’t want Arabs to buy homes.”

On the way back from visiting their home, a road is blocked off with a heavy police presence: barricades, blue lights, and the echoes of drumbeats. In recent weeks, police sirens seemed omnipresent. This time it was not another demonstration, but a Ramadan march of Jewish and Arab families from the bilingual school in Jaffa in the name of coexistence.

Attorney Mouhamad Kaboub, who has represented over 60 protected tenants in Jaffa in housing disputes, still believes Jaffa is the best available model for living together in the country. He recollects his fondness for his childhood neighbors: “I grew up with Bulgarian Jews who survived the Holocaust, and I celebrated Mimouna (a Moroccan Jewish festival to mark the end of Passover).” He also proudly represents Jewish clients who face similar entanglements with the land authorities, but even this amicability, with all its limitations, is threatening to collapse.

A new community has recently moved into Jaffa and has changed the rules of the game. The unprecedented evacuation of settlements in Gaza and the occupied West Bank in 2005, pushed the movement to search for new horizons: Israel’s “mixed cities” in a more cultural rather than territorial kind of redemption. Under the aegis of the Religious Zionist movement, and with the same government support denied to residents, new communities sprouted in Ramla, Lydd, and Acre.

In 2008, the movement arrived in Jaffa, fresh from the occupied West Bank. They established a series of institutions, including a pre-military academy and the yeshiva, in a bid to strengthen Jewish life in the area. Shandovitz says about a third of their funding comes from the government.

The sense of anxiety toward the new neighbors — the rabbis and the institutions — has justification: Mali once worked at Ateret Cohanim, an organization that seeks to purchase properties and push out Arabs from neighborhoods in East Jerusalem. During a post-prayer demonstration two weeks ago on one of Jaffa’s main thoroughfares, Yefet Street, the loudspeakers blared with mentions of the East Jerusalem neighborhoods of Silwan, which is facing mounting pressure from Mali’s former group, and Sheikh Jarrah, which has become a symbol of Palestinian resistance.

The process of gentrification and urban settlement can be separate but connected, urban anthropologist Daniel Monterescu told New Lines. “You can trace an economic trajectory of gentrification from the 1960s,” he explains, but settlement from the national religious community “would not have happened without economic gentrification.”

Whether it’s a yuppie from north Tel Aviv, or a hilltop youth, the economic impact on Palestinians is the same. But the national religious community “comes with a different approach.”

Be’Emuna, a property development company, marketed its 2009 apartment complex in Ajami exclusively to Jews. “It’s not that most of them want Arabs out, but they want to be in control,” Monterescu says.

Although reinforced policing is part and parcel of gentrification, the national religious community — serving in the military and hailing from the occupied West Bank — come with gun permits. “We are seeing the militarization of urban space. The settlers have the support of the undercover police, and this means more surveillance of the local population,” he adds.

“There is a sense of heightened risk, which means the police starts to behave more like the Israel Border Police,” Monterescu says, referring to the forces deployed in Jerusalem and the occupied West Bank. The title of his recent op-ed for Haaretz drew parallels with a more extreme example: “The Hebronization of Jaffa.”

After a staccato of alarmist, red “for rent” signs on Yehuda Margoza Street, Kaboub takes a sharp right. At the intersection there is a bourgeois bakery, a natural goods store, and an upmarket furniture store unironically called “Ethnic.” He stops at a half-demolished building, marked with both slick, ordered graffiti art, and the sort that would constitute vandalism. “This is the difference behind the Jaffa that they market to the world, and the real Jaffa,” he explains. On top of 1,200 to 1,400 families living under protected tenancy, a further 300 empty buildings that have the same status are boarded up. Between a row of parked cars and a blooming lavender tree, a homeless man reclines in a deckchair under a striated orange parasol, his face and kingdom of detritus illuminated by streetlights. “If the municipality actually cared, they could build a complex for him, and the families, right here,” he says.

To Kaboub, the focus on Amidar is misplaced. “Amidar is the end of the chain, but it’s the state that’s responsible,” he says, adding that it says on eviction letters that they are acting “in light of the intention of the owner, the government of Israel, and the Israel Land Authority.”

While some lawyers have left Amidar to defend the clients they believed the organization was exploiting, Kaboub insists that Amidar is generally cooperative and even cites examples where the organization has gone out of its way to help people remain in their homes. “But they don’t have much power,” he adds. As the body that deals directly with the locals, they have a different perspective. Israel Land Authority, on the other hand, “only deals with dry facts.” In many requests for media responses, the two bodies have blamed each other. Kaboub confirms that they are at loggerheads “all the time.”

In the end, it all comes back to one unwieldy and inequitable landlord: the State of Israel.

In 1996, the Israel Land Authority decided to sell off its absentee properties in the name of reducing bureaucracy. The first option went to the protected tenants, but the baton was soon passed onto tender on the free market, in part due to the same oppressive red tape, which seemed to coil around and strangle Palestinians only. Kaboub saw discrimination: There were similar cases of Jewish protected tenants, in the south Tel Aviv Hatikva neighborhood, where the Israel Land Authority and municipality struck an agreement to facilitate a discounted sale of the property. Like other organizations dealing with land — from the local level, such as Halamish, to national organizations with charitable status, such as the Jewish National Fund — a shared logic guides their policies, on both sides of the green line: Keep land in Jewish hands, and limit land for non-Jews. In the end, it all comes back to one unwieldy and inequitable landlord: the State of Israel.

As a result of the 1996 decision, as well as growing pressure from the government and municipality to go private, Amidar’s role has flipped. The public housing company is becoming a conduit to facilitate the transfer of homes onto the free market. Today, Monterescu describes “a coalition between public planning authorities and entrepreneurs.”

The invitations to tender, argues organizer Gharablé, “are the worst excesses of free market capitalism, and the natives don’t stand a chance.”

In unaccented Hebrew, Kaboub posits that the process is nothing short of a “financial transfer of the population.” Property prices in some Jaffa neighborhoods, he explains, have quadrupled in the last decade: “If you don’t have wealthy parents or you’re not a drug dealer, you can’t afford to live here.”

Most of his peers have been priced out of Jaffa and have instead bought property in Lydd or Ramla. For Arabs, the city’s borders are immutable. If they want an Arabic-speaking school, a mosque, or a church for their children, they must leave the area altogether. “The municipality certainly isn’t going to build them one,” he says.

The municipality has always sidelined Jaffa, Kaboub adds. He points to the numerous dog parks that have sprung up in the last few decades. “Why did they build these for dogs, but no housing for the residents?” he says. Then he recalled how, as a child, he innocently used to pick up syringes in Jaffa and present them to his father: “They never cared then,” he said. “They are not investing in Jaffa for (today’s) residents, but for the future residents.”