“Papa Africa, Papa Africa,” calls a voice in an alleyway in Laayoune, Western Sahara’s largest city, as Abdelkebir Taghia walks past fish stalls. Since 2005, this Moroccan of Sahrawi origin, now in his 50s, has devoted all his free time to helping and protecting migrants who try to reach Europe by crossing the murderous Atlantic Ocean from the Sahara region to the Canary Islands. In the process, he gained his nickname and established himself as one of the few indispensable direct observers of migration in this area. Official data is scarce here, hampered by a lack of access to migrants’ points of departure in a huge and sparsely populated region where one of Africa’s longest-running conflicts, over the status of Western Sahara, rumbles on.

In 2023, “The Atlantic route to the Canary Islands was once again the deadliest migratory region in the world,” according to Caminando Fronteras, a Spanish nongovernmental organization that defends human rights in border regions. It reports that just over 6,000 people died on the “Canary route” over the year, including hundreds of children and many on makeshift boats that disappeared without a trace. Taghia cooperates with Caminando Fronteras to try and count the number of victims and missing persons who leave from the Sahara coast. An estimated 1,418 of those who died during the crossing in 2023 set off from this stretch of coastline, on a route mostly taken at the end of a long and often violent migration process.

Since 2017, the number of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, Palestine, Syria and Yemen seeking to cross the ocean here has continued to rise, as the authorities have increased controls at the usual crossing points in northern Morocco. Migration is documented mainly on the arrivals side, by the Spanish Ministry of the Interior, which counts almost 40,000 migrants as having landed in the Canary Islands in 2023. In January 2024 alone, more than 7,270 migrants arrived in the archipelago, according to data from the Spanish authorities, over 10 times the number in January 2023.

Over many years, and with modest resources, Taghia has set up the only migrant aid association in Laayoune, covering the whole region. It raises awareness of the dangers of crossing and offers an alternative, facilitating integration into the local society and organizing discussion workshops for migrant women. “In the Sahara, Rabat, Marrakech or Tangiers, everyone knows me as Papa Africa. Since 2014, with my team, I’ve been able to help 7,000-8,000 people in the region. Looking back, I can’t believe it,” says Taghia, who is always the first to open the door of his association in the morning. The premises were set up in 2016, in a working-class district of the city near to the ocean, helped by the Catholic charity federation Caritas Internationalis and subsidies from the Moroccan government. The main hall, where a poster reads “Solidarity is not a crime, it’s a duty!” is crowded all day long. “We chose to be in the immediate vicinity of where the migrants live. Our aim has always been to focus on the most vulnerable population. It’s important to give them a place to express themselves, with all that they have endured during their migration,” he explains.

Historically, the region is a crossroads of cultures and peoples, and in the surrounding area the local population rubs shoulders with Wolofs, Peuls, Mauritanians and Ivoirians. “We’ve always been used to seeing Black people here. There is less racism than in the north of the country. The locals rent flats to migrants, which is not the case elsewhere in Morocco,” Taghia says, as he sips a Touba coffee from Senegal, the only one to be found in the neighborhood. Pointing to several flags of African and Middle Eastern countries on a shelf in the main room, the humanitarian estimates that between 15,000 and 18,000 migrants are currently in Laayoune.

The desert area of Western Sahara is bordered to the east by a front line between Morocco and the Sahrawi nationalist Polisario Front, known as the “wall of sands,” and to the west by the Atlantic Ocean. The varied and shifting behavior of migrants in this area makes it hard to ascertain their numbers: Some decide to settle and make Morocco their home, some make the crossing and others wait to cross. And the crossings depart from a wild coastline — a sort of no-man’s-land — stretching as far as the eye can see, for more than 680 miles. This expanse offers illegal immigrants a multitude of possible departure zones when night falls, as they hope to reach the Canary Islands, the small Spanish archipelago that has become the new gateway to the European Union.

Throughout the year, Taghia roams the coastline of dunes falling into the ocean, from Tarfaya in the north to Dakhla in the south, reaching out to migrants preparing to cross and making them aware of the dangers of the ocean. “We don’t encourage them to make the crossing because it’s too dangerous. They think that the Canaries are not far away, but the weather conditions are difficult, hence the many shipwrecks,” he says.

The vastness of the coastal strip facilitates the departure of makeshift boats from scattered crossing points. In places, it is sometimes possible to see the lights coming from the Spanish islands on a fine day. At the closest point, in the Tarfaya region, the Moroccan coast is 62 miles from the Canaries — a mere stone’s throw, but across some of the world’s most dangerous waters for migrants.

As Caminando Fronteras outlines in its recent report, migrants’ chances for survival on this route are strongly affected by relations between Morocco and Spain. Morocco has sought to use its willingness to oversee migration routes to gain recognition for its control of the region and its waters, and in 2023 the Spanish search and rescue agency Salvamento Maritimo did effectively recognize Moroccan control of the route by distributing maps drawn up by the kingdom. Rescues are delayed as the Spanish authorities encourage Morocco to take responsibility for migrants at sea, adding to the dangers faced by those making the crossing.

The flow of migrants taking the route from both Western Sahara and from the West African coast in general to the Canaries began in the 1990s and intensified in 2006 with the “pirogue crisis,” when thousands attempted the crossing from the coasts of Senegal and Mauritania to the Canaries, spurred by conflicts in several countries, tightening border controls at Ceuta and Melilla and the collapse of traditional fisheries under pressure from intensive fishing practices. This period coincided with the start of Taghia’s humanitarian involvement. “My commitment began some 20 years ago, when I was drinking coffee with friends here in this local cafe. At the time, next to this cafe, there was a detention center where migrants were held after being rescued at sea. They had just come out of the water, still wet, and they were going to be sent straight back to Mauritania at that point,” he remembers, adding: “I couldn’t stand by and do nothing. At the beginning, in 2005, I started to help by simply collecting and distributing clothes and food. It wasn’t as structured as it is today with the association premises. There was no help for immigrants, and nobody understood why we were helping them.”

From 2017, the association was able to observe an increase in the arrival of migrants seeking to cross to the Canaries. “First, the Moroccan authorities blocked departures in northern Morocco. Then, in Libya, migrants are victims of rape and human trafficking. And recently, in Tunisia, the authorities abandoned them in the desert. More and more migrants are leaving here, despite the risks of the fatal ocean,” he explains. But these are not the only reasons that people continue to come. “The flow increased enormously during and after the COVID crisis. With the problem of building sites and shops closing all over the world, and particularly in Africa, this has led to a loss of jobs,” he adds. With the number of crossings on the increase, the watchword at the association’s office is “raising awareness” of the dangers involved.

Taghia has surrounded himself with volunteers: two women, Aicha Sallasylla and Diara Thiam, and two men, Aboubakar Ndiaye and Abdou Ndiaye, all from Senegal. This team is a symbol of what Taghia has achieved over the past 20 years. Some of those now working with him considered the crossing to Europe themselves. It was after meeting Taghia that they decided to stay in Laayoune to help prevent further deaths and to try to help others envisage a future in Morocco like their own.

Every morning, the group gathers in the meeting room to plan the tasks ahead and take stock of the weather situation, worrying about the survival of any migrants who might take to the ocean. “When we are confronted with dozens of corpses, regularly, we have to take the lead. We must raise awareness among young people so that they take the necessary measures. People’s lives are important, which is why we turn to community leaders. But some of them are smugglers, so our message doesn’t always get through,” says Taghia, who organizes the monthly awareness campaigns with Thiam. According to Taghia, nearly 1 in 10 of the boats run aground. Sallasylla, a volunteer with the association who wanted to cross in the past, says: “Clandestine migration is financed by family investments. Relatives sell their land to get to Europe, hoping to be able to pay off the journey. By the time they get here, it’s often too late, because they’ve already taken out a loan with a bank or their family.” “Cross or die” is the migrants’ motto. In debt or under family pressure, migrants feel they have no choice but to continue their journey. “All this encourages people to leave. And we can only convince two or three people out of 10,” she admits.

Not far from Laayoune, Taghia and Abdou walk along an endless sandy beach. They usually come here when there is a risk of shipwreck, hoping to find survivors. They are close; Taghia saved Abdou from his attempted crossings. Abdou, 38, has since become a volunteer with the association. “This beach was a starting point, but now the gendarmes are on the lookout,” he says, pointing to soldiers on patrol. The two men watch the sunset over the Atlantic Ocean, worried.

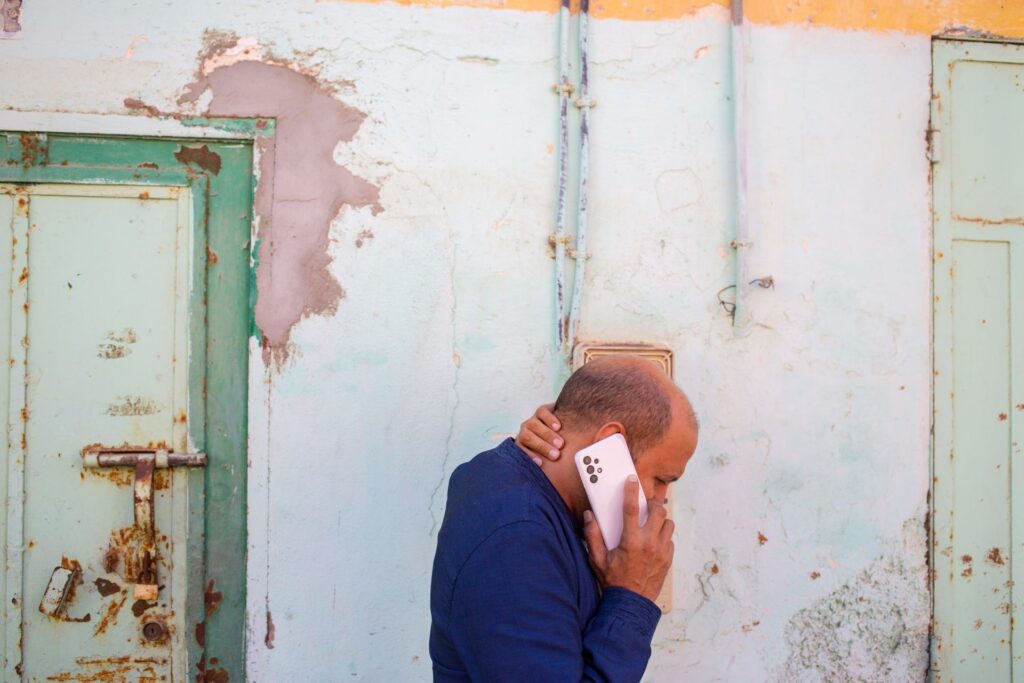

Over the last few days, as is often the case, dozens of people have gone missing in the open sea. Abdou shows a message on his phone: “SOS in the Atlantic! We were alerted to the presence of a boat with 47 people in distress coming from Tarfaya. We lost contact 42 hours ago. To date, we’ve had no news.” It was sent by Alarm Phone, a group of volunteers offering telephone assistance to people in distress in the Mediterranean, the Aegean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, with whom the association works. Testimonies from families and alerts from civilians in the departure areas are vital to the rescue operation. “When we receive these alerts, we share the GPS coordinates of the last known positions with the Moroccan maritime forces,” Taghia explains.

On the beach, Abdou discusses the mechanisms of clandestine migration in the light of his own story, under Taghia’s benevolent gaze. Abdou has tried to cross three times. He entered Morocco illegally in 2012 and for three years he worked in fish-freezing factories. Every year, at the time of Eid el-Kebir, a public holiday, Abdou traveled to Tangiers with friends, with a single goal in mind: the crossing to Europe. Each time they arrived in northern Morocco, Abdou and his friends tried to find a so-called “captain” to take them out to sea. “The captains are often sub-Saharan fishermen who want to immigrate. The fishermen don’t pay for the journey, and in exchange, they guide us out to sea. It’s a win-win situation,” Abdou confides, adding: “In the north of Morocco, we can’t use motorboats, because we don’t want to make noise and be spotted. So, we paddle.” Abdou was arrested twice in a forest before he had even touched water, and the third time at sea.

In 2015, Abdou found a new job in a factory in El Marsa, a few miles from Laayoune: “That’s where I heard about Papa Africa. Since then, it has given meaning to my life, by giving me the opportunity to help people,” Abdou says, looking out over the ocean. Taghia, moved, replies: “You have to have love and desire. You must know how to live for others.” Since then, Abdou has decided to save lives alongside Papa Africa, a commitment that has earned him respect and turned him into an unofficial leader of the Senegalese community in Laayoune.

While the association works to save lives, others take advantage of the “European dream” and turn it into a business. “There are two kinds of prices for the Canaries: the ‘classic pack’ for which you pay $550 on departure and $2,100 on arrival. And then there’s the ‘guaranteed’ option, which costs $3,200 if you arrive at your destination,” explains Abdou. It’s a financial windfall for the local mafia and the smugglers. A small 9-meter Zodiac inflatable boat carrying 58 people can make $150,000. According to our information, the people at the head of the networks are Moroccan nationals. They never physically move. They organize the clandestine crossings from their homes and instruct the sub-Saharan smugglers to bring the Zodiacs to the beach.

For Taghia and Abdou, this illegal business is distressing: “It hurts us to see people dying. We are eyewitnesses to these tragedies. We regularly see inanimate bodies washed ashore. Families with no news contact me to find out if their loved ones are still alive,” Abdou says. To facilitate the search, Abdou visits the local morgues. “The family sends me a passport photo and a photo of the missing person taken in everyday life. The last time, I was able to identify a corpse in a morgue thanks to a scar on the forehead,” says Abdou.

The association’s goal of saving lives is ultimately at odds with the smugglers’ activities, and when asked if he has experience of pressure from the mafia, Taghia replies: “Not directly. But I hear things here and there.” Hundreds of criminal networks involved in migrant smuggling and human trafficking are dismantled every year by the Moroccan authorities, sponsored since 2019 by the EU and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, with a budget of 15 million euros allocated over three years for Morocco and the rest of North Africa (Egypt, Libya, Algeria and Tunisia).

In Abdou’s view, the smugglers are not the only ones responsible for the human tragedies in the Atlantic: “The European Union is guilty of these deaths. It allocates large subsidies to third countries to combat immigration. Instead of externalizing its border protection, the EU could fund humanitarian development projects or vocational training centers in the countries of departure,” he says, adding: “In Senegal, it’s mainly the fishermen who are leaving. There are no fish left because of the fishing contracts signed with China and South Korea, which practice industrial overfishing. They’ve taken everything.” According to a report published by the Foundation for Environmental Justice, almost two-thirds of Senegalese fishermen say that their income has fallen over the last five years. One of the causes of this decline is overfishing, notably the destruction of breeding grounds following the arrival of foreign industrial fishing fleets off the Senegalese coast. “In five to 10 years’ time, there won’t be any young people left in Senegal,” Abdou says.

In June 2023, the European Commission presented an EU action plan on the migratory routes of the Western Mediterranean and the Atlantic, supporting the outsourcing of border management and strengthening “the capacities of Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal and the Gambia to develop targeted actions to prevent irregular departures.” To prevent migrants from organizing themselves to make the crossing to the Canary Islands, Morocco is deploying measures to keep them away from the departure areas and move them to other towns.

In support of integrated border and migration management, Morocco received 44 million euros from the EU between December 2018 and April 2023. Yet for Taghia, the tactics funded in this way are inadequate. “Morocco has a duty to limit departures under bilateral agreements. The financial aid granted by the EU is mainly distributed to the Moroccan coast guards and security services. They mustn’t take an exclusively security-oriented approach. We need to have a long-term humanitarian vision, aimed at vocational training and the integration of migrants in their countries of origin or when they arrive here,” he says. “In Laayoune at the moment, there are arrests everywhere, because recently, following several shipwrecks that left many dead and missing, the authorities have arrested and moved migrants all over the Sahara, to keep them away from the departure areas.”

According to some witnesses in the region interviewed by New Lines, migrants are regularly subjected to police violence and forced displacement in efforts to keep them away from the departure points and dissuade them from taking to sea. New Lines was able to visit a migrants’ hostel to gather testimonies from direct victims of police violence and view several videos documenting human rights violations against migrants. To protect the victims, we will not give details of their identities or backgrounds.

A man who testified that he had been subjected to police violence on several occasions said: “During the day, we hide to avoid police raids. When the police arrive at the houses to arrest us, some of us jump off the roofs to try and escape, and some of us break a leg.” Several victims told of how these “displacement” operations to move migrants away from the departure zones are carried out. “Often, the police are in civilian clothes. When we ask to see their identity papers or badges, they hit us,” one person said. “They force us into vans or buses, then take us to a center outside Laayoune. We remain detained in unsanitary conditions for a few days until we can fill a bus with 40 to 50 people to take us to other Moroccan towns.” Measures are different for migrants rescued at sea or arrested by coastguards at the time of crossing, who are systematically incarcerated in detention centers and released after several days. “I left my country because of a political crisis, so I wanted to take refuge in Morocco. I had no intention of crossing, but the violence here might force me to take the risk,” a young woman from Ivory Coast told New Lines in tears.

Taghia has just returned from Dakhla, where he met with the Senegalese consul, installed in the coastal town in April 2021, to obtain permits for access to the detention center in Laayoune, in the hope of finding Senegalese migrants reported missing after shipwrecks or rescues, and providing news to their families. According to our information, there are four detention centers in the area: one on the outskirts of Laayoune, two in Dakhla and one in Tan-Tan.

“Morocco is caught between the African countries and the European Union,” Taghia says. The Cherifian Kingdom does not wish to carry out mass expulsions of sub-Saharan immigrants to their countries of origin, which could jeopardize its strategic and diplomatic relations with the rest of Africa. In this context, from 2014 the Moroccan government adopted a new comprehensive national strategy called “immigration and asylum,” aimed at regularizing the situation of irregular migrants present on Moroccan territory and facilitating their social integration. This initiative, partly funded by the European Union, is one of the policy levers intended to reduce the migratory flow to Europe. In January 2024, the UNHCR estimated that there were 10,280 refugees and 9,386 asylum seekers from 50 different countries in Morocco. “In Laayoune, in 2015, a Migrant Monitoring Commission was set up to facilitate access to healthcare, and regularization. But we don’t have the exact figures for the number of migrants regularized in the region, because they are not public data. The Regional Human Rights Commission and the Wilaya have helped to integrate migrants. Today, migrant children can enroll in school. And doors have started to open for humanitarian projects,” Taghia says.

“We don’t stop migration at the last minute. If someone has traveled from Guinea to Algeria and then on to Morocco, you can’t ask them to stop along the way. So, we must meet their economic needs by giving them a professional perspective here,” he says. Taghia is aware that the situation of migrants remains fragile and precarious across the region. “We would like to be able to obtain grants from the European Union to help us develop humanitarian projects like the ones we are currently setting up,” he points out. He perseveres, using his own contacts and seeking support from the Catholic Church in Laayoune. He regularly crisscrosses the city to convince companies to recruit migrants. “We’ve become a sort of employment agency,” he says with a smile. “This year, we managed to find work for 25 people who were already qualified in their country of origin. Today, they are working, for example, in gardening, mechanics or catering.”

Since 2023, he has been trying to create partnerships with local schools to provide vocational training for migrants, making it more likely that they choose to stay and avoid tragedy at sea. Amie Gueye, 28, is one of them. A Senegalese mother, she came to Morocco with her husband and two children. In the salon where she is training to become a hairdresser, she explains that the association helped to find her the opportunity.

Day after day, Abdou’s phone keeps ringing. One morning, he listens to an audio message — “I’ve arrived in Spain” — looking reassured. Abdou confides: “He’s a Burkinabe who’s had a problem with his leg since he was born. He wanted to go to Spain for treatment because, despite several operations in Burkina Faso, it wasn’t getting any better,” adding, “Like Papa Africa, my days are focused on the needs of migrants. My phone even rings at night. Yesterday, I took a woman who was about to give birth to the hospital by taxi at 3 in the morning.” The needs are regularly medical, and the association activates its personal networks to take care of the migrants. Sometimes there are happy days, like this time with the new baby, and Taghia decides to drive his team to the hospital. A rock fan, he puts on a song by an artist he likes; Sallasylla starts humming to the tune of Dire Straits’ “Sultans of Swing.” The volunteers arrive enthusiastically with gifts for the mother and baby Abdou has helped. Sallasylla dances as she enters the room, Taghia shouts “Congratulations,” while Thiam takes the newborn in her arms and exclaims: “He looks just like his brother.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.