In November 2021, a major event occurred in the French literary world: A 31-year-old Senegalese writer, Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, won the country’s most prestigious literary award, the Prix Goncourt, for his novel “La plus secrète mémoire des hommes” (“The Most Secret Memory of Men”). It was the first time an author from sub-Saharan Africa had won the prize, and it stirred discussions pertaining to Francophone literature, colonialism, postcolonialism, as well as bringing to the fore the saga of a forgotten author.

Mbougar Sarr’s book tells the story of a young Senegalese writer living in present-day Paris who is captivated by the discovery of a novel published in 1938 by another Senegalese author, a mysterious T.C. Elimane. Hailed as the “Black Rimbaud,” Elimane experiences a fleeting moment of glory, but then, accused of plagiarism, he disappears, leaving behind an ill-fated novel.

One of Mbougar Sarr’s characters in the novel says: “African writers and intellectuals, beware of certain acknowledgments. Of course, bourgeois France, in order to have a clear conscience, will honor one of you, and it might even be an African who succeeds or who is seen as a role model. But deep down, believe me, you are and will remain foreigners, no matter the value of your work. You do not belong.”

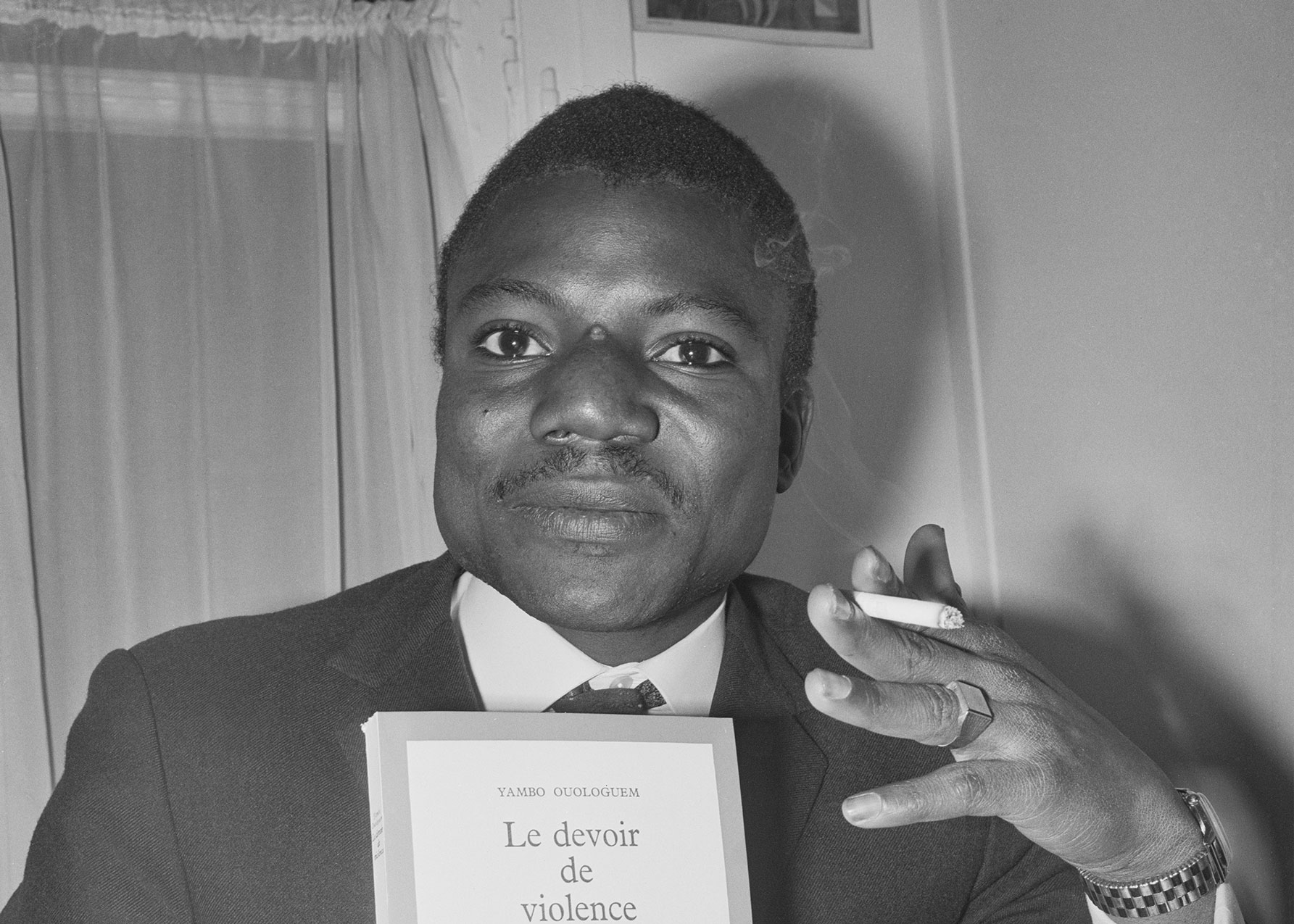

The inspiration for Mbougar Sarr’s novel began with the tragic and true story of Malian author Yambo Ouologuem, who at age 28 won the 1968 Prix Renaudot, France’s second-most prestigious literary prize, for his novel “Le devoir de violence” (“Bound to Violence”); a first for an author from the African continent. The book, a sweeping portrait of African history with plenty of sex and violence, was hailed as a masterpiece and translated into more than 10 languages. When it was released in English in 1971, a New York Times Book Review reflected the thinking at the time: “Great novels are rare; great novels by Africans are even more rare, but they are on the way … ‘Bound to Violence,’ a first novel, is a great one and would be even without the 1968 Prix Renaudot.”

In 1972, after penning a few more books, some under pseudonyms, Ouologuem was accused of plagiarism for “Le devoir de violence.” After fruitless attempts to defend himself, he returned to Mali, devastated, never to publish again.

With Mbougar Sarr’s 2021 Prix Goncourt, suddenly, the backstory of “Le devoir de violence” and its author came alive, and academics, publishers and literary agents who had been involved with the late Ouologuem dug out their files and brushed them off.

Ouologuem died in 2017, and many of the people who participated directly in the publication of “Le devoir de violence” are also dead, including François-Régis Bastide, his editor at the renowned French publishing house, Le Seuil, and its publisher Paul Flamand. Ouologuem’s U.S. publisher Helen Wolff at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; Ralph Manheim, his first English translator; and the two authors Ouologuem was accused of plagiarizing, André Schwarz-Bart and Graham Greene, are no longer alive either.

In 1972, an article in The Times Literary Supplement had accused Ouologuem of lifting and using several pages from Graham Greene’s “It’s a Battlefield.” Furthermore, it was discovered that a month prior to its publication in 1968, Bastide had sent a copy of “Le devoir de violence” to Schwarz-Bart, with a letter saying he had noticed some similarities with passages in Schwarz-Bart’s 1959 novel “Le dernier des Justes” (“The Last of the Just”), which had won the Prix Goncourt the year it was published.

While some see his borrowings as plagiarism, others call it intertextuality — drawing on specific writings and reshaping them into his texts. But before addressing the details of these accusations, let’s get introduced to the man. There is no doubt that Ouologuem was a fascinating, multifaceted character and a gifted author whose book, “Le devoir de violence,” marked a turning point for French-language literature from the African continent.

Born in 1940, Ouologuem belonged to a cultured and privileged family of landowners in Bandiagara, the main city in the Dogon region of Mali, where El Hadj Omar Tall, a political leader, military commander and Muslim scholar, had established the Toucouleur Empire in the 19th century.

Here, we must introduce Christopher Wise, an American academic and a Fulbright professor at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso in 1996, who had read texts by Ouologuem in graduate school when postcolonial studies didn’t exist in the U.S. “Chinua Achebe [a prominent Nigerian novelist] was read in anthropology and not in comparative literature classes,” he said.

Wise was one of the few Westerners to have met Ouologuem after the author moved back to Mali definitively in 1978. This encounter changed his life, he said, and led him to turn the focus of his studies on El Hadj Omar Tall and Sahelian culture for 25 years. In the preface of his book, “The Yambo Ouologuem Reader,” Wise described how Ouologuem and his ancestors, members of the Dogon aristocracy, had converted to Islam in the late 19th century.

Besides being a landowner, Ouologuem’s father was also a school inspector during French colonial rule, who, it is said, raised the French flag and had his son sing “La Marseillaise.” Ouologuem was a brilliant student and finished secondary school in Bamako, the capital city, before going to France in 1960, the year Mali gained independence. He was admitted for preparatory classes to the prestigious Lycée Henri-IV, which led to his admission at an elite professional school where he prepared for a doctorate in sociology and received a degree in English. During this time, Ouologuem familiarized himself with Parisian culture and began to write fiction. Undoubtedly, few Parisians he encountered knew much, if anything, about the prodigiously rich, multilingual and multiethnic culture he came from. By 1968, he was married to his first wife and had two daughters.

Jean-Pierre Orban, a Belgian-born author and editor who spent his childhood in the Democratic Republic of Congo, became familiar with Ouologuem’s literature much later in 2014, when he was working on the second edition of an erotic book by the Malian author.

Those who were fascinated by the Ouologuem legend had to wait until 2018, when Orban published an essay that gave the first detailed overview of Ouologuem’s process as a writer, providing invaluable information and insight into the young author’s beginnings. Orban gained access to Le Seuil’s Yambo Ouologuem archives, which he pored over painstakingly. He was able to discover Ouologuem’s budding writing career and consult the readers’ reports on Ouologuem’s submissions to Le Seuil and correspondence dating to 1963. Orban showed us how Ouologuem, at only 23, had lofty aims when he submitted his first manuscript to the distinguished publishing house. He was persistent when faced with rejections and continued to send Le Seuil reworked manuscripts over the next few years. Le Seuil saw promise in the young writer, and in 1967, in yet another rejection letter, the man who would later become his editor, Bastide, wrote: “Surely, there is a great ambition in your writing. You are, if I may say so, bound to write a masterpiece.” In early 1968, after many back-and-forths, Le Seuil accepted Ouologuem’s manuscript, “Le devoir de violence.”

It is interesting to note that Ouologuem’s address at the time was that of Présence Africaine — the cultural magazine, bookshop and publishing company founded in Paris in 1947 to give voice to the African and Black world. From its inception, Présence Africaine had played an active role in the drive for French decolonization of Africa, the pan-African movement and the Négritude movement, which was spearheaded by Senegalese poet and future President Léopold Sédar Senghor as well as Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, among others. Présence Africaine was the nucleus for Black intellectuals in Paris. Ouologuem’s name appeared in the magazine in 1963 and 1964, but as far as we know, his literary endeavors were only submitted to Le Seuil. Five decades later, Mbougar Sarr’s first two novels were published by Présence Africaine.

During this period, the editorial director of Éditions du Dauphin, who declined to be named, met Ouologuem. “He came to us because he wanted to write children’s books and confused our publishing house with another,” the editorial director said. “He was polite, brilliant and very talkative; once you got into a discussion with him, there was no end in sight. I remember he seemed a little naive, he was generous, and he laughed a lot. In fact, he was hilarious. During our conversation, he mentioned he had a book coming out with Le Seuil, but he was worried, because he was unknown and wanted to send me the manuscript to read. I read it and told him, because you just have a feeling as an editor, ‘This is going to do really well, you will most certainly get a prize.’ Africans were gaining their independence, and he was showing Africa in another light. I didn’t hear anything else from him and then he received the Renaudot.”

“Le devoir de violence” is a bold, extravagant and explosive text, at times hilarious and sarcastic, which careened through centuries with descriptions of violence, cruelty and sex (including gay sex). None were spared in his stark assessment of African history, and it was precisely this equitable and “profoundly ethical” account, as Christopher Wise puts it, that shocked and excited readers. At the same time, it also provoked the ire of African intellectuals involved in bringing attention to colonial rule.

“White colonialism is but a slim chapter in a series of crimes, which begin with the dynasty of African dignitaries, then those of the Arab conquest, and finally, the period specific to the French occupation,” Ouologuem had said in an interview with the French public radio and TV ORTF in 1968, with a cigarette hanging off his lips and looking incredibly composed for a 28-year-old.

His novel, Ouologuem told “Jeune Afrique” magazine in 1968, “is about forcing yourself to become aware of the real problems. … As the title of the book indicates, we have a ‘duty of violence’ to undertake a forward-looking vision, which allows for neither bad faith nor idleness.”

In the preface to his book “The Yambo Ouologuem Reader,” Wise writes: “Many credit Ouologuem with delivering the final deathblow to Senghorian négritude, with clearing the way for a more honest literature divested of the sickly longing for a false African past. For these readers, ‘Le devoir de violence’ signaled an important new direction in African letters, a fiercely courageous, post-independence literature. For others, Ouologuem’s ‘untimely’ portrait of African history revealed far too much, bringing to light horrors that many preferred to forget.”

By 1969, Le Seuil archives revealed, over 80,000 copies of “Le devoir de violence” had been sold. However, Orban’s research showed that the relationship between Ouologuem and Le Seuil publisher Flamand had become strained, as they exchanged correspondence about misunderstandings and pecuniary issues. The author sent a letter to Flamand asking him to increase the number of books Le Seuil had promised to publish from five to 15. He was considering writing an opus for Le Seuil, he said, under the general title “The Body of Civilizations,” which would include two more Africa-centric titles, and then move to the United States, Latin America, and the Western and Asian Worlds.

It remains unclear why Le Seuil did not publish Ouologuem’s next work, a sharp, satirical essay titled “Lettre à la France Nègre” that Wise translated as “A Black Ghostwriter’s Letter to France,” published in 1969 by Editions Nalis. In it, he laid out a plan for aspiring African novelists to write bestselling crime novels and addressed the then French president Gen. Charles de Gaulle. He began his letter: “To the left, to the right! My dear General, before I abandoned my own prehistory to flee to your country, every night, from sunset to sunrise, the troubadours in Africa would sing to me your praises, telling me how privileged I was to be allowed to sit upon your knees, and to suck on a gaullipop [lollipop], which you lavishly bestowed upon me.”

That same year, Ouologuem published “Les mille et une bibles du sexe” (“The One Thousand and One Bibles of Sex”) — an unbridled and comical description of the erotic adventures of the French bourgeoisie. Although Ouologuem used a pseudonym, Utto Rudolf, he signed the preface with his name, stating that he was the editor of the work. It wasn’t the kind of title Le Seuil would publish, so Ouologuem went to the editorial director at Éditions du Dauphin.

The former editorial director told New Lines that Ouologuem had written the manuscript of this book in her office over a six-month period because he needed “to be around people.” The book was a “reflection of Parisian social gatherings.”

“It was a trend he found himself involved in because of his notoriety; he was invited to parties everywhere. We edited and cut out quite a bit because in those days people were sensitive about stories that today are banal. There was the (libertine) club Roi René and Madame Claude, where people met but it was hidden, and they didn’t want to be mentioned. But he wanted to write something literary, not a voyeuristic book,” the editorial director said. Orban edited the second edition of “Les mille et une bibles du sexe” in 2015, which was published by Vents d’Ailleurs under Ouologuem’s name.

While Ouologuem was working in the Éditions du Dauphin offices, he also tried his hand at another style of writing — romance novels. “We had a collection. It was like a factory. We published four a month. He said he wanted to try writing one as an exercise. He had a risk-taking side to him,” the former editorial director said. Ouologuem wrote two romance novels under the pseudonym Nelly Brigitta that were published in 1968 and 1970.

In 1971, the English-language edition of “Le devoir de violence,” translated by Manheim — who had also translated Sigmund Freud, Marcel Proust and Louis-Ferdinand Céline, among others — was ready. In the U.K., the hardback edition was published by Secker and Warburg, and the paperback by Heinemann’s African Writers Series, forerunners for publishing contemporary African literature at the time. Ouologuem traveled to the U.S., where his novel was published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. There, looking dapper in a suit and tie, he gave interviews in fluent English to The New York Times, Life magazine and other publications, appeared on TV and met Muhammad Ali.

According to Le Seuil archives, while he was in the U.S. and unbeknownst to his French and American publishers, Ouologuem signed a contract with the publisher Doubleday for at least one novel and several books on contemporary African history for $30,000, an enormous advance at the time. In correspondence to Flamand, his U.S. publisher Wolff wrote that she had shown great interest in Ouologuem’s next work, titled “Les Pèlerins de Capharnaüm” (“The Pilgrims of Capernaum”), but had assumed that it was up to Le Seuil, his publisher, to sign the contract.

More misunderstandings between the author and publisher, an apparent lack of interest on the part of Le Seuil for “Les Pèlerins de Capharnaüm” and Ouologuem going rogue with other publishers, including those in France, led to a breakdown of his relationship with his publishing company, and above all with Flamand.

A little more than a year after “Le devoir de violence” was published in English, accusations of plagiarism were leveled against Ouologuem. It began with a research student who spotted borrowings from one of Graham Greene’s books. Ouologuem’s British editor, James Currey, told New Lines, “Graham Greene found it annoying. It was a piddling little stupid thing. … I hope it doesn’t happen today; I hope we’ve grown up slightly. I had forgotten about this, but rereading my two and a half pages about the controversy [in Currey’s book “Africa Writes Back”], it was fundamentally a waste of time. I am as mystified now as I was at the time.”

Greene did not press charges and accepted the British publisher’s offer to include appropriate acknowledgment in future copies of the book. In the U.S., however, the chair of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich decided to withdraw and cancel all future publications of “Le devoir de violence.” Moreover, Harcourt demanded $10,000 in damages from Le Seuil. (According to the archives, Le Seuil later ended up paying about half of that sum to the U.S. publisher.) From then on, the affair blew up in the French media, where borrowings from a short story by Guy de Maupassant, a crime novel by John D. MacDonald, the Bible and the Quran were spotted.

In 1968, when Ouologuem’s editor wrote to Schwarz-Bart with a copy of Ouologuem’s book, Schwarz-Bart, who was also accused of plagiarism when “Le dernier des Justes” was published, wrote back that while he was troubled and hurt by the fact that his own publisher, Le Seuil, hadn’t seen fit to tell him earlier about Ouologuem’s reworkings of several passages from his book, he wrote: “I am in no way worried by the use that has been made of ‘Le dernier des Justes’ … I have always looked at my books as apple trees, happy that my apples will be eaten and happy if now and again one is taken and planted in different soil.”

At first, Le Seuil and Ouologuem attempted to defend themselves in the press. The author claimed that Le Seuil had removed quotation marks around the paragraphs in question and explained his “literary technique” of borrowing and reworking texts. Ultimately, Ouologuem was left to defend himself on his own. He was savaged in the French press, and his fall from grace was complete. It is said that he had gotten into a brawl and spent time in a psychiatric hospital, although no records of his stay have been confirmed. He then returned to Mali definitively, embittered and determined, never to have anything to do with France again. Family members speak of him arriving in Mali ill and say that he was poisoned in France. Soon after, Ouologuem turned toward religion, became a devout Muslim, and refused to speak of his time as a famous author. He also remarried and had three children.

Most academics now agree that the plagiarism charges against Ouologuem, which occupies a small percentage of his book, fall into what can be called a “gray area” as plenty of writers, including T.S. Eliot, Graham Swift and P.D. James, have used the same method of intertextuality. The damage to a brilliant young writer, however, was already done. In November 1982, according to Orban’s research, Le Seuil stopped publishing “Le devoir de violence.” Heinemann followed suit.

In 1997, Wise met Ouologuem twice at his home in Sévaré, Mali. Ouologuem had reluctantly agreed because Wise was accompanied by Sékou Tall, a direct heir of El Hadj Omar Tall, who had agreed to help him “as he recognized the importance of doing research on Yambo Ouologuem,” Wise said. “Ouologuem wouldn’t respond directly to any of my questions. He said, ‘this is not an interview.’ But he talked.”

Their first conversation was about literature, the second about his religious beliefs. “He was a very pious, spiritual man; he was the real thing. He had an aura about him. He was an extraordinary man. The Yambo Ouologuem who went back to Mali became a strong man with religious convictions. … His Islam was Tijaniyya, or Sufi, and totally different from Wahhabism. He told me, ‘The biggest enemies of Black Africans are racist Arabs who have been satanically blessed with oil,’” Wise said.

Echoing the observations made by Éditions du Dauphin’s former editorial director, Wise said, “Ouologuem could have been a stand-up comedian. He could fire off one-liners; he had everyone in stitches.”

Meanwhile back in France, Ouologuem’s daughter Awa from his first marriage went on a mission to rehabilitate her father’s name. It’s not entirely clear how she legally obtained the power of attorney to manage her fathers’ rights to his work, but in 2001, she went to Pierre Astier, the founder of Serpent à Plumes, who published a number of Francophone authors from the African continent and the Caribbean, such as Emmanuel Dongala, Alain Mabanckou or Dany Laferrière. Astier reedited both “Le devoir de violence,” for which Wise wrote the preface, and “Lettre à la France Nègre.”

“We were worried that the accusations from the late 1960s would resurface and that the polemic would begin again,” Astier told New Lines. “But nothing happened. On the contrary, French academics started to talk about him.”

The next year, Serpent à Plumes was acquired by a larger publishing house, and Astier became a literary agent and later got Ouologuem’s estate on board as a client.

With the rights that Awa obtained, Wise was able to translate, “Le devoir de violence” and other texts again, along with Michel Tinguiri. In 2008, “The Yambo Ouologuem Reader” was published with Africa Research & Publications, and Ouologuem’s work was available to English readers once again. “There were lots of people talking about him in academic circles [in the U.S.] but the problem was you couldn’t get the book. I wanted to teach it to my students, but it wasn’t available,” Wise said.

Ouologuem was not pleased that his work was being republished. Astier and Orban were uncomfortable about going against his will, but they felt strongly that his work was important and should be available to a larger and newer audience. “You sometimes have to separate an author from their work. Think of Kafka, he wanted all his work to be destroyed after his death,” Astier said.

Wise suspects that even if Ouologuem was unhappy, he was pleased that his name was being cleared.

Ambibé, Ouologuem’s youngest son, told New Lines that his father’s story was known in the family (and in the region). “But we weren’t supposed to talk about it. We knew he had been famous, but we didn’t know the details. In 2003, I was shown photos of my father in a suit smoking a cigarette and I thought, is this really him? I only knew him wearing a Boubou [a flowing tunic worn as an outer garment]. He didn’t speak to us [children] much because he didn’t want us to be interested in what had happened to him,” he said.

Ouologuem wanted to shelter his children from outside influences and didn’t want them to go to school, but their grandmother intervened, Ambibé said. “This man who lived through so many things didn’t want us to go to school and become Francophone. He wanted us to learn about Arabic culture and writing. We first went to school without him knowing about it. Our grandmother said she was sending us to run errands,” he said.

Ambibé and his siblings couldn’t walk around with books at home, so they used to leave them at the neighbor’s house. “When he found out, I had already been going to school for six years. He was furious, but my grandmother stood up for us. We liked being at school with our friends. At home it was too serious. … At home we spoke Dogon and Bambara; my father didn’t want us to speak French, he called the French cowards and parasites, but when he heard us speaking French among each other, he would answer in French because this was the language that he was the most comfortable in,” he said.

In what might be seen as a surprising decision, around the time of Ouologuem’s death on Oct. 14, 2017, Orban, with Awa’s blessing, suggested that Le Seuil publish “Le devoir de violence” once again “to rehabilitate the novel in its original home.” Awa gave back world rights to Le Seuil for the novel, and Orban chaperoned the publication of the third edition of “le devoir de violence” which was published in 2018.

In 2019, Astier met Ambibé in Bamako and his agency became the representative for Ouologuem’s estate, even though Le Seuil retained the rights to the seminal work.

So, what’s happening now?

When Mbougar Sarr won the Prix Goncourt in 2021, interest in Yambo Ouologuem was reignited. Ambibé was present at a two-day conference on Ouologuem, held recently in Rabat to inaugurate a chair on African arts and literature at The Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco. There, he told New Lines that his father had never stopped writing. “It was his passion,” he said. There are manuscripts, he added, but since his father’s death in 2017, the siblings in Mali haven’t yet looked through his archives.

A Franco-Senegalese journalist, Kalidou Sy, is working on a documentary about the writer and recently contacted Ouologuem’s family and everyone who has been involved with his literary heritage.

On the publishing side, Astier has negotiated with Le Seuil to cede the francophone rights to two African publishers, Éditions Tombouctou in Mali and Vallesse Éditions in Côte d’Ivoire. He also persuaded Le Seuil to sell the English-language rights to Other Press in New York. Other Press will also be publishing Mbougar Sarr’s “La plus secrète mémoire des hommes” in 2023 and expects to publish “Le devoir de violence” in 2024 with Manheim’s translation. Some passages, however, will need to be put into context, the publisher Judith Gurewich said.

Since “Le devoir de violence” was first published in 1971, there are certain words that are no longer acceptable. For instance, throughout Manheim’s translation, “négraille” and “nègre” have been translated as “niggertrash” and “nigger.” Wise explained that in his own translation, he “refrained from employing the [racist] English word.” He instead translated négraille as “black-rabble.”

“This editorial choice is not motivated out of fear of offending the reader — it is doubtful that the reader who is easily offended will bother to read Ouologuem in the first place. The [racist] term does not accurately convey what is intended by the French word nègre, which is closer to either ‘Negro’ or ‘Black’ than the stridently offensive term,” he said.

Ambibé and his family, as well as publishers and academics in Mali, seem unperturbed by Ouologuem’s provocativeness. Ibrahim Aya, the publisher at Éditions Tombouctou, said, “Our introduction won’t reflect a politically correct view — this isn’t what preoccupies people here — but it will be more about putting the book into context. It will be good for people to see how authors wrote in those days,” he said, hoping that the Malian edition of “Le devoir de violence” will be ready by early 2023.

“Ouologuem doesn’t find Africa to be better or worse than anywhere else,” said Malian academic Mamadou Bani Diallo. “All endeavors should be based on deconsecrating and demystifying, and Africans should be aware that we can’t develop amidst lies and hypocrisy.” He added that an important aspect of Ouologuem’s writing was that he “openly addressed the question of sex, which is generally a taboo and surrounded by negative connotations in Africa. … He makes it a normal subject, free from scandal. Some erotic passages from ‘Le devoir de violence’ and especially ‘Les mille et une bibles du sexe’ are veritable sex encyclopedias.”

Ouologuem, said Jean-Pierre Orban, “was a genius, but not a saint.”

Ambibé is intent on seeing his father’s books become available to all and used in various university programs. “It’s a way to rehabilitate him,” he said. “It’s an African book for Africans that should be used by Africans.”

And then, apart from these endeavors, there are all of Ouologuem’s unread manuscripts.