Iran was set ablaze last year after Mahsa Amini was taken into custody and beaten to death by the country’s morality police in Tehran for wearing “improper hijab.” The killing of the 22-year-old struck a deep chord among Iranians, inspiring protests in more than 100 cities throughout the country, marking the largest uprising Iran had seen since the 1979 revolution. Government reprisals were severe, with hundreds if not thousands of protesters arrested and tortured and several of them executed.

“The volume of art and creative responses that we’ve seen to this uprising is really unprecedented,”says Nahid Siamdoust, author of “Soundtrack of the Revolution: The Politics of Music in Iran” and host of the podcast “Woman, Life, Freedom.” “Even in comparison to 1979, I think this is unprecedented.”

“In a sense, the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ revolution is a revolution that’s formed by culture, by art, by music, by poetry,” Malu Halasa, literary editor of The Markaz Review, tells New Lines magazine’s Danny Postel. It’s that art that is the subject of her new book, an edited anthology titled “Woman, Life, Freedom: Voices and Art from the Women’s Protests in Iran,” which was released this month.

“Music is still strictly regulated. Dance is certainly not permitted on the streets. I think it is because of the imposition of these rules that opposition necessarily takes this form.”

Unlike previous, more reformist protest movements in Iran, the Mahsa Amini protests became genuinely revolutionary. That revolutionary feeling was channeled into a great range of art forms, but especially music and hip-hop in particular. “Hip-hop in the West has lost its power. We haven’t really had conscious rap for quite a long time,” Halasa says. But in Iran, she adds, “even before the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ movement, hip-hop was very powerful. It was critical of the status quo. It wasn’t just party music.”

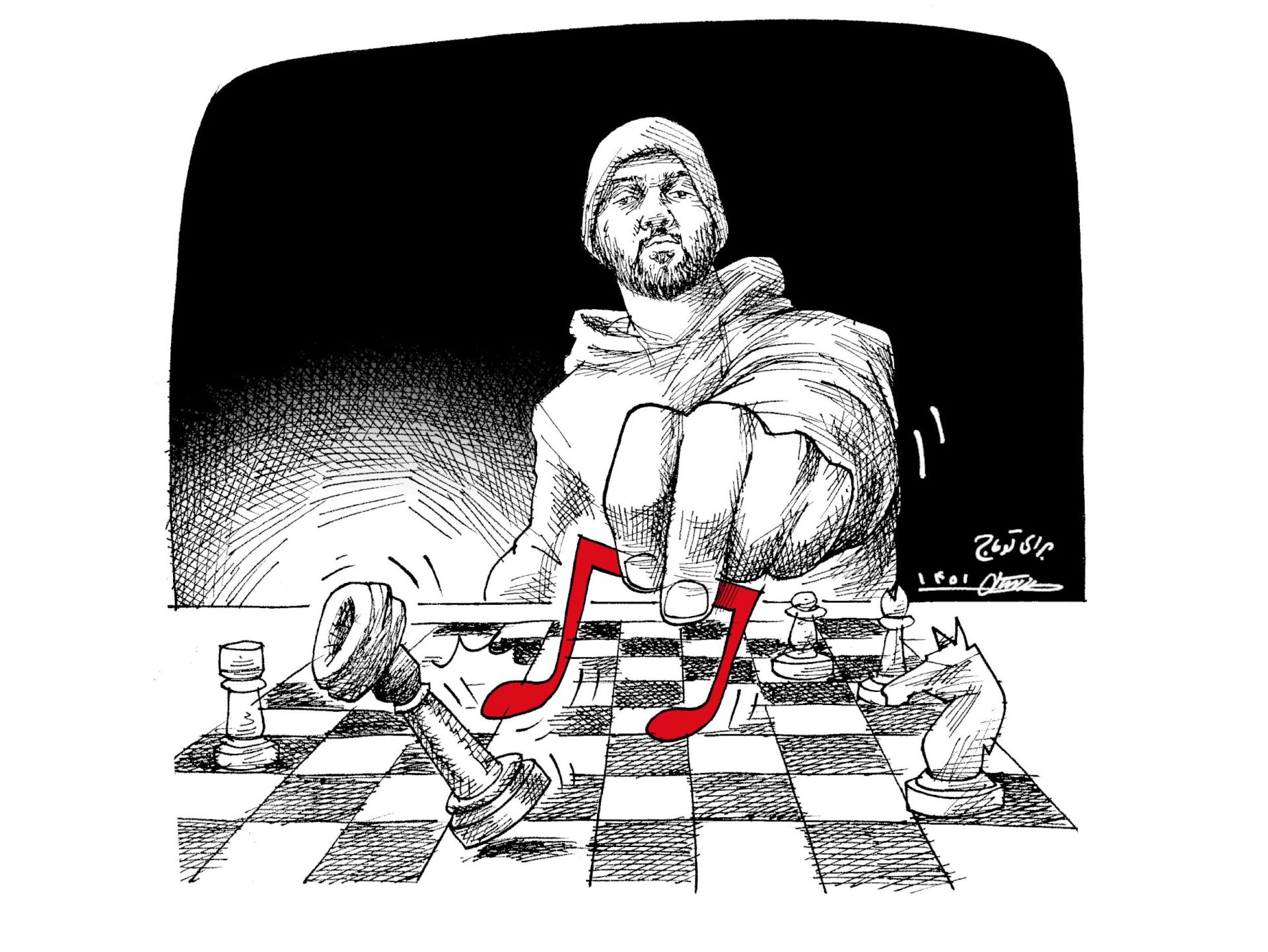

Artists can pay a high price for speaking out against the regime. For his blistering lyrics in support of the movement, a 32-year-old rapper from Esfahan named Toomaj Salehi was arrested and eventually sentenced to six years in prison after being held in solitary confinement for 252 days. He is one of many artists who have become figureheads of the wider movement, his songs played at protests while demonstrators wield placards with his name and face.

It’s no accident that musicians have become such integral and iconic parts of the movement, Siamdoust says.

“Music is still strictly regulated. Dance is certainly not permitted on the streets,” she explains, “I think it is because of the imposition of these rules that opposition necessarily takes this form.”

Produced by Joshua Martin