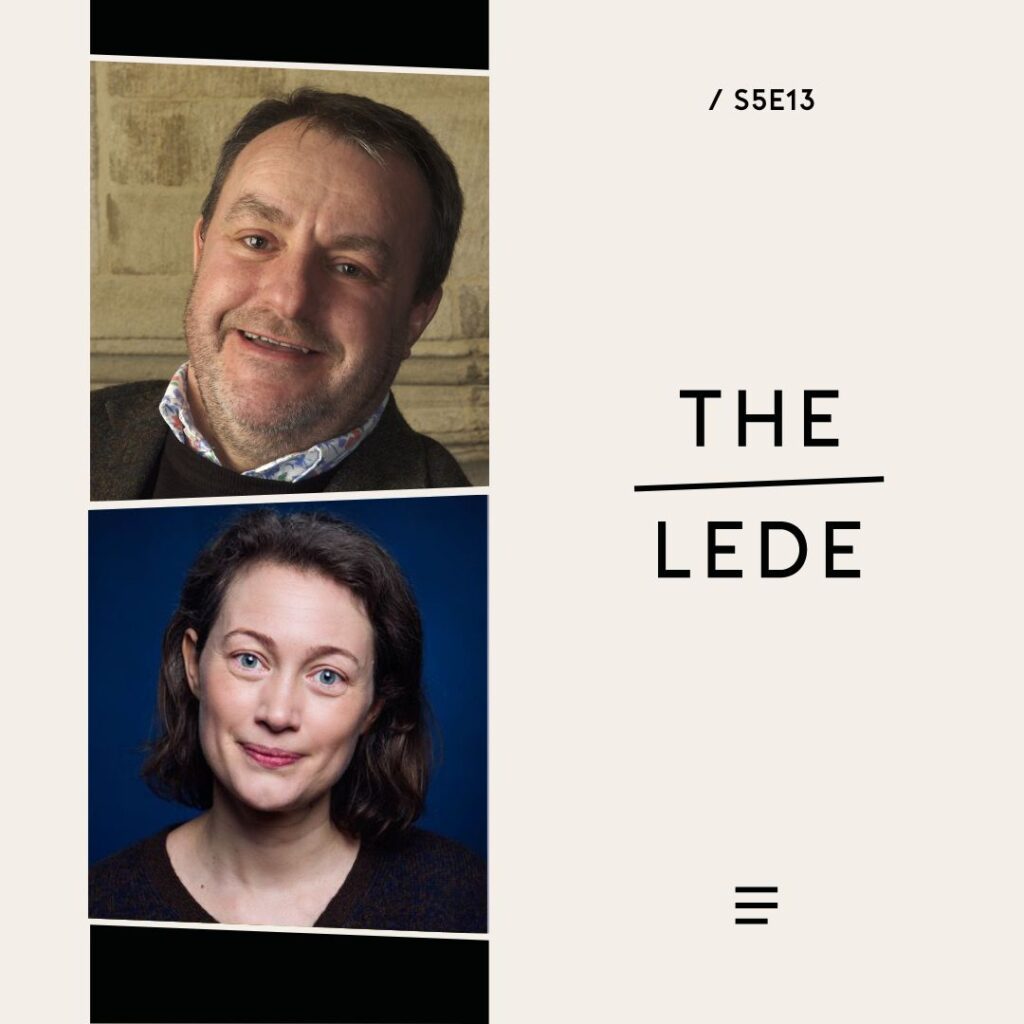

Hosted by Lydia Wilson

Featuring James Montgomery

Produced by Finbar Anderson

Listen to and follow The Lede

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Podbean

James Montgomery, Sir Thomas Adams’s professor of Arabic at the University of Cambridge, has devoted himself to researching and translating poetry from the pre-Islamic period of the Arabian peninsula, known as the “jahiliya.” Few historical sources exist for the period, explains Montgomery, meaning that “the poetry is a portal into the world. So we have to interpret the world through the poetry, and the poetry is the only thing we have to go on in order to establish this world.”

Montgomery joins New Lines Culture Editor Lydia Wilson on The Lede to discuss his latest book, “In Deadly Embrace: Arabic Hunting Poems,” which offers a new translation of hunting poetry by Abdallah ibn al-Mutazz, a poet writing in the ninth century, after the establishment of the Islamic caliphate. The period, says Montgomery, displays a fascinating overlap between the pre-Islamic world, which was dominated by the concepts of fate and time, and the post-Islamic world, in which the standout theme was an omniscient or omnipotent god. “The wise thing about the poetry is it doesn’t seek to reconcile the two, it allows both to coexist,” says Montgomery.

“If you’re translating a 10th-century philosopher, one of the greatest minds of his age in Arabic, and you translate it into English, and the English sounds like someone that you wouldn’t want to sit next to in the train for 10 minutes, it seems to me you have failed.”

Although the poetry is not as singular an insight into the early Islamic world as pre-Islamic poetry is for the jahiliya, early Islamic hunting poetry remains an important window into the period, says Montgomery. “The iconography and the ritual of hunting in this very sophisticated courtly society was in order to qualify a prince not only for wars, but also to qualify him as a potential leader,” he says.

Some of Montgomery’s recent translations of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry sat unfinished for decades, but the language was so foreign and so alien that he was unable to commit himself to a finished product he was satisfied with. The inspiration he was searching for came from an unlikely place. “I realized that YouTube and the internet was what this project needed. I couldn’t do it without the online resource of amateur falconers filming themselves, of chat groups, of websites,” he says.

For Montgomery, in order to produce a convincing translation of a poem, it is necessary to completely immerse oneself in the lexicon of the author. “We have a terrible tendency in the 21st century to think that imagination is effectively untrammeled in nothing but make-believe,” he says. “Imagination, as far as I can see, requires a huge amount of mental discipline before it can be allowed to work its magic. So for me, it was really important to try to know as much about what we call the “realia,” the everyday real aspects of this material, in order to compile a distinct enough dataset in my mind that would then enable me to try to enter into the poetic universe of the poetry.”

Journeying to the pre- and early Islamic periods means that Montgomery feels little drive to produce his own poetry. “What I really love the most is that the words of the Arabic poets give me the creative vehicle,” he says. “Each version of each new poem that I embark upon gives me the challenges — aesthetic, intellectual, imaginative, creative — that I seem to need. That gives me everything that I’m looking for.”

Further reading: The Seven Hanging Odes of Mecca