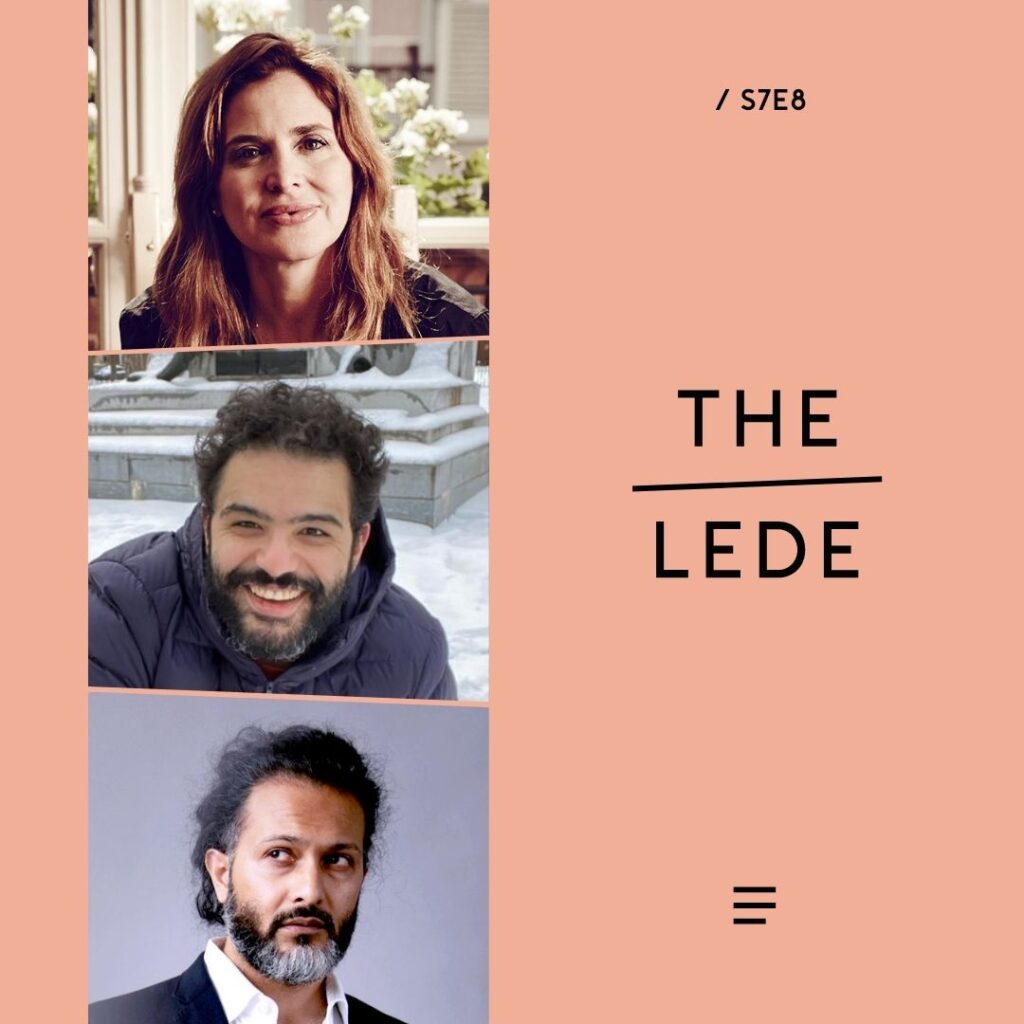

Hosted by Faisal Al Yafai

Featuring Janine di Giovanni and Kareem Shaheen

Produced by Finbar Anderson

Listen to and follow The Lede

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Podbean

Janine di Giovanni’s last visit to Syria was not a happy time. “I remember feeling so despondent,” she tells New Lines’ Faisal Al Yafai on The Lede. “We were just leaving them there and they were going to have to live under this brutal regime. It was really painful. Now, I am hopeful for the new government. I have confidence in them. I want to see it work.”

After the collapse of former President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, di Giovanni’s most recent trip was a completely different experience. As executive director of The Reckoning Project, an organization dedicated to strengthening accountability, she was focused on what her organization could do to help bring about accountability and justice for the hundreds of thousands of victims of the former regime and arguing for a role for those elements in the building of a new Syria.

“It’s really crucial that people see justice working because ultimately, if you don’t have justice after a war as brutal as Syria then you will never have healing.”

“I think it’s really crucial that people see justice working, because ultimately, if you don’t have justice after a war as brutal as Syria then you will never have healing and there will be revenge killings, there will be attacks, and ultimately a war could start again.”

The Reckoning Project dedicates much of its resources to trying to bring accountability for crimes committed by occupying Russian forces in Ukraine. With so much experience of that conflict, di Giovanni is well aware that it is seen very differently by outside observers to that in Syria, or neighboring conflicts such as that in Gaza. “I’m absolutely determined to see justice for Ukrainians who have suffered terribly under Putin,” di Giovanni says. “I’m just saying the international community’s response to what happens to a European country where people are white and to a Middle Eastern country where people are brown is entirely different.”

Also joining Al Yafai on The Lede is New Lines’ Middle East Editor Kareem Shaheen. For journalists, the pursuit of justice through the course of their work is “a fool’s errand,” he says. “More often than not, it’s a change in the facts on the ground, and the political situation and the military situation, that leads to the change necessary to hold these people to account. You have to just anticipate that maybe at some point, something like that is going to happen and your job is not to bring about that change because it’s totally out of your hands. Your job is simply to find out what happened and tell people what happened.”

Shaheen believes that Syria does in fact have the mechanisms at its disposal to pursue accountability. “The protraction of the war and the involvement of so many outside parties did have a silver lining to it, which is that it created the space for Syrian civil society to, almost by trial and error, evolve into something quite strong and meaningful and grassroots.”

“I think that what we’ll see over the next few months and years in Syria is how people grapple with the return to normalcy from that state of extreme, and how much those extremes have affected their sense of self and how they’ve affected their sense of their own humanity,” Shaheen says. “This search for justice is situated within that broader question of how Syrians see themselves as a society after such a brutalizing conflict.”