Listen to this story

In the early hours one Wednesday morning, I hitched a ride on the back of a motorcycle and zipped through the silent, dusty streets of Accra, Ghana’s capital. My destination was Kantamanto Market, located between a disused train station, a polluted industrial zone and Accra’s largest slum. It is the biggest and oldest clothing resale market in West Africa — possibly the world — where 30,000 people hustle and toil six days a week to scratch out a living selling secondhand clothing.

My driver parked his motorcycle under the awning of a booth outside the market and introduced me to a shoe vendor named Petee — a muscular man with bloodshot eyes and a booming voice. Staring at me from his cutoff T-shirt was the face of Tony Montana in “Scarface.” Petee explained that twice a week, he bought third-selection shoes — that is, the most worn-out and cheapest — by the bale from a Ghanaian wholesaler, who got his shoes from “Babylon.”

“Our colonial masters,” he added.

I came to Kantamanto in the fall of 2021 because I wanted to see for myself how used clothing from the Global North was being sent around the world to be resold or destroyed. I had been writing about fashion for many years, but usually from the vantage of the runway, museum gallery or luxury shop floor — not the shipping terminal or dumpsite.

For most of my life, I had accepted the marketing myth that donating my old clothing was a good deed. Fashion companies around the world, like H&M, Zara and Gap Inc. have pushed this sustainability narrative to reassure consumers that they can keep on consuming without feeling guilty about the clothing they toss away. Now, I was determined to learn how the business really worked, how a leviathan market in one of West Africa’s busiest cities functioned, and how the lives of the people who worked there were bound to the ebbs and flows of a global economy whose workings they did not grasp, but whose effects they felt every day. What I discovered in Kantamanto was not just the waste produced by the so-called democratization of fashion, but a more complex tangle of creativity and constraint. Like the bales of secondhand clothing the vendors cut open each morning, Kantamanto is a place made of equal parts human potential and suffering.

By 4 a.m., dozens of vendors had already spread their shoes on tarps on the ground, and the air was filled with a cacophony of voices: “10 cedi,” “10 cedi,” “7 cedi!” (When I was in Ghana, $1 was equivalent to just over 6 cedis. Now it is worth closer to 11.) Prospective buyers frantically sifted through the rubble of shoes, using their phones for light or clutching flashlights in their mouths as they examined sandals, sneakers and old oxfords, looking for pairs that would turn a profit.

This was Shoesellers’ Alley, tucked just outside the still-closed gates of Kantamanto’s warren of stalls. When the market opens at 6 a.m. each day, vendors set up in small wooden booths piled high with their wares, divided into subsections by gender and category — everything from used tracksuits to bras to starched white dress shirts. You can have your clothing altered on the spot by a tailor, and if you buy in bulk, you can pay a young woman to carry it all on her head for you.

Secondhand clothes have been resold at Kantamanto since the 1980s, when structural adjustment policies forced Ghana to open its markets to foreign imports. But with the rise of fast fashion, this complex ecosystem has begun to collapse. Global fashion industry production doubled between 2000 and 2014, and it has bounced back beyond pre-pandemic levels following COVID-19 lockdowns. Current estimates put global fashion and apparel production at between 100 and 150 billion items per year. The U.S., the U.K. and China are the world’s biggest consumers, with the average American buying around 60 items of clothing a year and wearing each one about 10 times. The end result: The clothes we buy end up in local landfills or charity shops, or in the hands of intermediaries who send them on to secondhand markets in the Global South — like Kantamanto.

Ghana is one of the Global South’s most voracious and sophisticated consumers of secondhand clothing. This situation extends back to Ghana’s time as a colony and captive market of Britain, made worse when Ghana’s economy was forcibly liberalized during the African debt crisis of the 1980s. Though Ghana has a rich artisanal textile heritage, its industrial fashion sector is moribund, unable to compete with multinational behemoths or the low prices of the Global North’s castoffs. According to data compiled by the Observatory of Economic Complexity, in 2021, Ghana imported $214 million worth of secondhand clothing, becoming the largest importer of used clothing in the world. These bales of clothes came primarily from the U.K. ($81 million) and China ($48 million).

Once the clothes arrive at the port, however, the business becomes hard to track because so much of it occurs in the informal economy. Still, for Ghanaians, the knock-on effects of this trade are huge. A government official in the Ministry of Trade who was not authorized to speak on the record told New Lines that out of Ghana’s population of over 34 million, about 5 million people are involved in the business: importing, shipping, trucking, carrying, selling, repairing and reselling clothes. Bales travel to Ghana’s most remote regions, and even to customers in neighboring countries, such as Burkina Faso. For people like Petee, secondhand clothing is not just what they put on their back but what puts fuel in their car, their children through school and food on the table.

Between transactions with customers, Petee told me his story. “I’m a street gangsta, I don’t have nothing,” he said. Petee was born and raised in Kumasi, Ghana’s second-largest city and the seat of the Ashanti Kingdom. As a young man he moved to Accra in search of work, and after a stint working as a bus driver, he wound up selling shoes in Kantamanto. Like many of the people I met at the market, Petee worked at least 12-hour days. At night, he slept in the construction site of his half-completed house, each day saving up a little more to finish it.

During a lull in transactions, Petee suggested we go into business together, with me shipping him shoes from the U.S. or the U.K. He clapped his muscular arm around my back and smiled hard against my protests. “Everybody is a businessman,” he insisted. “We could make a lot of money, my friend.”

Thankfully, another customer arrived, a young man with thick, hipsterish glasses. He plucked a pair of shoes from the pile and offered a price. Petee made a counter, speaking in pidgin, which I could only partially understand. The sky was turning a lighter shade of indigo with the approach of dawn, so Petee dropped his price. The two men came to an agreement, and the buyer stuffed his new pair of black dress shoes in a burlap sack slung over his shoulder.

Whatever doesn’t sell must eventually be thrown away. For the many subpar garments that arrive in Kantamanto, the market is not a happy place of recirculation but a dumping ground. Vendors and laborers who try to get ahead find themselves trapped in debt from purchasing bales of clothing they can’t turn a profit on. Waste clothes wash ashore on Accra’s beaches, clog its sewers and have filled its main landfill, Kpone, beyond capacity — forcing it to close years earlier than engineers had predicted. An estimated 40% of the clothes imported into Accra are disposed of in ad hoc landfills, dumped on poor communities at the edge of the city or burned in open-air pits with other waste. This clothing, improperly disposed of, adds to Ghana’s worsening air and water pollution crisis, degrading the environment and human health in ways researchers are only just beginning to understand.

All of this textile waste also only further exacerbates the world’s climate crisis. The global fashion industry is thought to produce between 4% and 8% of the Earth’s annual carbon emissions. (Estimates vary because of how poorly we understand the global fashion supply chain.) The effects of climate change were already being felt when I arrived in Ghana — hotter temperatures, droughts, floods, declining crop yields. Every day, people were arriving at Accra’s bus stations from Ghana’s rural interior, many of them children of subsistence farmers who could no longer feed their families.

By 7 a.m., the sun had risen over Kantamanto, and the hot air began to thicken with fuel exhaust and the shouts of hawkers. Cabs inched through thronged intersections while motorbikes zoomed through the cracks. In the midst of this chaos, a steady stream of 40-foot shipping containers were arriving by truck, loaded with fresh tons of baled-up secondhand clothing. Thousands of buyers pass through the market each day, making hundreds of thousands of transactions. Spending time in Kantamanto is a bit like visiting the Alps or the Grand Canyon; its vastness and frenetic pace inspire both awe and terror. There is, as Petee said, a lot of money to be made.

Like much of the used clothing that comes to Ghana, I arrived from the U.K. I started my journey at a warehouse on the outskirts of Croydon in South London, where I met Alison Carey at her family’s textile recycling and resale business, Chris Carey Collections. Alison has a round face, with dyed blond hair, black designer glasses and a thick South London accent. In addition to running the -business founded by her mother, Alison was the vice president of the Textile Recyclers Association (TRA), a U.K. trade group that represents what is left of the British rag trade. She was also driving the truck that day to make pickups. Every time we spoke, she seemed to be putting on a brave face, but her problems, like the clothes in her sorting facility, had been piling up.

Fuel prices and other overhead costs were up, and with all of the closet-clearing during lockdown, there seemed to be an ever-increasing volume of poor-quality fast fashion flooding her collection bins. In 2021, the global market for secondhand clothing was worth $96 billion. By 2026 it is projected to more than double, reaching at least $218 billion. Alison’s job is to separate the wheat from the chaff or, increasingly, to find a needle in a haystack. She flat out refuses to buy overstock from charity shops because she says the quality of the garments is so bad, preferring instead to use her own collection bins. “While some of the charities do understand that it is a waste stream,” she said, “others just see it as a revenue stream.” When we drop off bags of pilled sweaters and old stained T-shirts at the local charity shop, they wind up selling it on because it has little chance of being bought in a glutted domestic market.

Around 25 metric tons of clothes arrive in the warehouse per day, the weight of about six large African elephants. In the back corner loomed a mountain of unsorted clothes 15 feet high, just dropped off that morning. Only 40% of the clothes Alison receives are actually baled and sold on to importers. Because most clothing is composed of many kinds of fibers, chemically melting down a T-shirt and recycling it into a new one is very difficult, and rarely economical. Whatever Alison doesn’t bale for resale is downcycled into rags or insulation, or sent to landfill.

A few workers were sorting clothes for bales going to Ghana, so I offered to pitch in.

“Try to find a nugget,” Alison suggested.

A space on the counter was cleared for me, onto which Alison dumped out a trash bag of clothing. It was my job to sort the contents into one of the 72 categories of items such as “white office dress shirts” and “ladies party dresses,” and subsort those according to grades: A, B or wiper. Though I was wearing a mask, the reek of mothballs shot straight up my nose. Inside were a South African cricketing sweater and a battered, elaborately decorated navy school blazer. These, I decided, might be collectible, so I pulled them for Alison’s vintage shop. As I continued sorting, however, I mainly found fast-fashion tops, pit-stained or coming apart at the seams (wiper), old children’s pajamas (grade B) and a ball of worn-out thongs, which went straight into the garbage.

Though careful sorting makes Alison’s bales high quality, the labor costs involved are significant. When I visited the warehouse, a sorter’s salary started at 10.85 pounds an hour (around $13.75), and it takes six months to become proficient. Others have to be trained to operate machinery, like the two men I watched loading up a bale’s worth of clothing into a compressor. When they pulled a lever, it slowly crushed a loose pile of clothes into a solid prism wrapped in plastic, a bit like a car being crushed in a junkyard.

Less scrupulous textile recyclers who aren’t members of the TRA sell unsorted bales. “They’ve already creamed off whatever is worth taking,” Alison said. Importers are left with what amounts to little more than garbage. Technically, sending waste textiles abroad is illegal in the U.K., EU and U.S., but the laws are difficult to enforce. In Europe, legislatures are introducing extended producer responsibility requirements, or EPR, to force brands to take legal responsibility for the full life cycle of their clothes. In the U.K., trade groups, like the TRA, are pushing for similar, voluntary measures. However, to achieve their circularity goals, these EPR schemes require a massive, local textile-sorting and recycling infrastructure that does not currently exist, and what little capacity there is appears to be shrinking. Alison is part of a dying breed.

In Ghana, the increasingly poor quality of the bales coming into the country has not gone unnoticed. Alison pulled out her phone to show me a clip from an Australian report about Westerners dumping unwanted secondhand clothing on Kantamanto. In the video, an importer cut open a bale of clothes and sorted it for the news anchor. “Bola,” he said angrily, meaning “trash.” He pulled out stained and torn items from the pile and held up a sweat-stained tailored women’s jacket for the camera.

The Australian interviewer then began explaining the economics of the resale business; this importer paid 90 Australian dollars for this bale, he said. It was an absurdly low price, Alison interjected. The price the importer paid was half of what Alison charged; she wasn’t surprised he hadn’t found much to resell. But the video, she felt, was making textile recyclers like her look like the bad guys.

“All of these things are driving me to the point of insanity because someone who knows the industry, like we do, knows that that bale shouldn’t even be there anyway,” she said. “And all that customer’s done is bought something cheap in an attempt to make a bucket load of money.”

After a few weeks at sea on a container ship, the bales of clothing arrive in Ghana’s port of Tema. On the docks, metal shipping containers are inspected, fumigated and put on trucks to be taken to warehouses across the city. The red dirt road leading out from the port of Tema to the highway that stretches along Ghana’s coastline is often choked with 18-wheelers. Though the importers are small in number and comparatively removed from the action of the market, they are perhaps the most influential link in the chain, setting prices, responding to local demand and greasing the wheels of government to get their products to customers.

Though it was only a few blocks from the market, Marlvin’s office felt far removed from the chaos. (To protect confidential business information, Marlvin and many other sources are referred to by their first name only.) Inside his air-conditioned office, Marlvin was seated in an ergonomic office chair, with a window behind his desk and a large bookcase full of binders detailing transactions going back 10 years. He wore a matching gray shirt and pants, tailored to show off his muscular physique. The pocket was accented with colorful Ghanaian kente cloth piping.

When I met him, Marlvin was dealing with a drop in demand and an increase in shipping costs due to the lingering effects of COVID-19. That month, he was only bringing in two or three shipping containers a week, but in the past, he brought in twice that. His clients were businesspeople like him, resellers who sold high volumes with slim margins to smaller resellers, and so on, down the chain until they arrived in the stalls of Kantamanto.

Lately, he’d started thinking about changing suppliers to search for cheaper prices, maybe in China. On my way to his office, I had spotted two young Chinese men with clipboards in their hands, likely exporters looking to make deals. But Marlvin’s father wanted to stick with the U.K.

“Everybody knows that U.K. is better quality,” Marlvin said.

This didn’t make sense to me, since so many clothes coming from the U.K. are actually made in China or Bangladesh. The U.K. itself was a brand, he admitted, something his customers trusted and wanted printed on the sides of their bales, a legacy, he guessed, from when Britain was a colonial power in the region.

I asked Marlvin what he knew about waste from the secondhand clothing trade and the environmental problems it was causing.

He bristled at the suggestion. He was a job creator and a sustainability advocate, he told me. He was “trying to extend the lifespan of clothes” while helping resellers put “food on the table for their family” and letting customers “feel good about what they wear.”

“I think I’m really making a positive impact on society,” he concluded.

On the other side of the market, I went to visit another importer who seemed in every way the opposite of Marlvin. Okirie operated out of a storage unit in a dusty, sunbaked courtyard, surrounded by a hive of similar storage units run by his extended family. In the unit behind him, Okirie estimated that there were at least 80 bales, bearing labels from all over the world: Canada, Australia, Germany and the U.K., with many more stored in a warehouse.

At a glance, he looked less like a successful businessperson and more like the hawkers I saw hustling in the market, dressed in a white Adidas shirt, jeans and sandals. To pass the time, he was playing cards with a man in a tight-fitting polo. Okirie scanned his hand, his eyes moving over the cards like the beads of an abacus.

“You are making money every day, at least 100 cedis, 200 cedis, and there’s 30 days in a month,” he said. “Add it up, that’s more than somebody working in a bank. But obviously, he comes here with suits,” he said. “They will respect him more than you, not knowing that you are richer than him. That is the irony of the business.” He punctuated his remark by slapping down a card on the table.

Though importers like Okirie may not command the same respect as professionals in Ghanaian society, they have enormous economic power, setting the terms of sale in the market. Many customers buy bales on credit. “Especially the older women, and they tell you about family issues,” Okirie explained. “They want five bales, but they can only pay for one bale.”

This arrangement became especially problematic when the market shut down during the first wave of COVID-19 in 2020. Without income from clothing sales, vendors began defaulting on their loans, he said, and importers like him were left holding the bag.

“You have to absorb their debts. You’re human.”

That afternoon, out of necessity, I decided to do a little shopping. My luggage had been lost in a transfer in Amsterdam, so all I had to wear were the clothes on my back. My photographer, Kwame, said he knew a few places; he had once been a T-shirt reseller at Kantamanto and still had friends who worked in the market. In fact, Kwame’s entire wardrobe was sourced from “Kanta,” as locals call it. On the day we first met, he was dressed in a black T-shirt printed with a vortex graphic and the words “once you go black you never go back” in all caps. Over his shoulder was a small black shoulder bag in the shape of Darth Vader’s helmet.

With the only clothes I had already soaked in sweat, I needed to find something to wear until my lost luggage turned up. Among dozens of starched white dress shirts for office use, I saw a wrinkly linen one from Gap hanging from a vendor’s rail. Technically it was a women’s top, but I wasn’t picky, and it seemed perfect for the humid weather. Kwame asked the price, and when the vendor replied, he sucked his teeth and shook his head. He gestured for me to follow him elsewhere. Because I am a white man, Kwame explained, the price was far higher than it should have been.

“Chale, I come back later,” he said.

In an area devoted to athletic shorts, Kwame pointed out a woman as she cut open a fresh bale, with resellers jostling to get first dibs on her castoffs. In another stall, among piles of T-shirts, I noticed a familiar brand from back home: a maroon T-shirt with the crest of the University of Cambridge.

Along with the shirt, I grabbed a pair of gently worn Levis for 50 cedis. The jeans I chose were nicely faded, but for many Ghanaians that made them less appealing. As I wandered the market, I passed two men dipping sponges in bowls of blue liquid and scrubbing pair after pair of old jeans to give them a uniform, azure hue. The table underneath had turned navy from years of scrubbing. After dyeing the jeans, they applied a watered-down cassava paste to stiffen the fabric. Ghanaians like secondhand clothes, one of the men explained, but they want them to look new.

Early in the morning at a busy corner of Kwame Nkrumah Avenue, I met up with Liz Ricketts, co-founder of The Or Foundation. Aside from the intensity of purpose radiating from her gray eyes, she looked like a summer camp counselor, dressed in shorts and a T-shirt, with a backpack, waterproof hiking sandals and a baseball cap. Liz is what people in Ghana call an “obroni,” a white foreigner. She and her partner, Branson Skinner, left their jobs in fashion in 2011, and have since split their time between the U.S. and Ghana in order to document the problems in Kantamanto and help the people who work there through outreach, medical care, financial relief and advocacy.

Because of how little academic research has been conducted on the secondhand clothing economy in Ghana, The Or Foundation has (for better or worse) become the principal authority on the inner workings of Kantamanto. Fixing the injustice of the secondhand fashion system is Liz’s life mission, and after years of effort she finally had the money to make an impact.

In June 2022, The Or Foundation became the recipient of a $15 million donation from Chinese fast-fashion giant Shein to study and mitigate the effects of clothing waste at Kantamanto. Given Shein’s documented history of labor violations, toxic levels of lead in their clothing, and contribution to the global overproduction of clothing and resulting textile waste, the decision to accept the donation was bound to cause controversy.

Before Liz announced the partnership at the 2022 Global Fashion Summit in Copenhagen, she had given her usual speech about the problems faced by the people who work at Kantamanto and the injustices of the global secondhand clothing trade.

“Several people in the audience were crying,” she recalled. “People were looking at me with pity, like, ‘We have to help her. This is so sad,’ etc. And I hate that. And then five minutes later, I make an announcement that we’re getting help, and the reaction is: ‘How dare you?’”

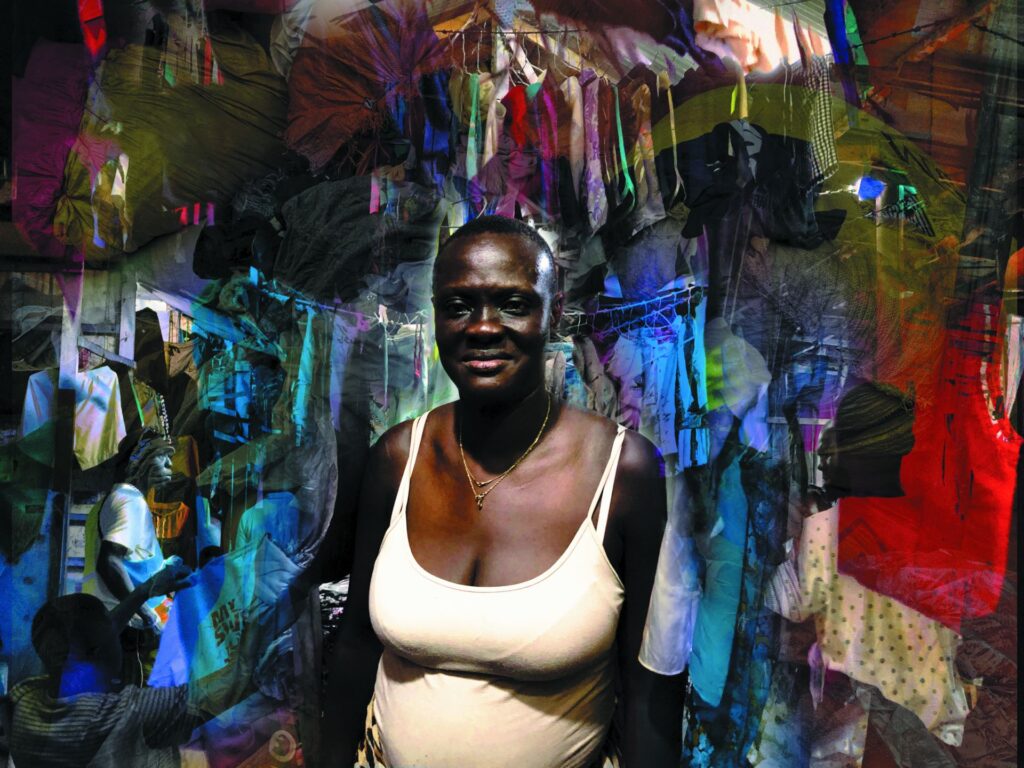

In a section of the market near the entrance, Liz took me to meet two women, Abene and Janet, who, between them, have over 20 years of experience selling secondhand clothing. It was late morning, and the air inside the covered market was thick. Fabric debris and dust sparkled in the rays of light that shone through the cracks of the metal roof. Liz described Abene as a “boss lady,” whom the other women in her section of the market turn to when they need help. Janet, however, was struggling. They worked in the women’s tops section of the market and had each gotten stuck with low-quality bales, though they had come out of the experience differently.

Janet is a middle-aged woman with cropped hair and a weary smile. When I first met her, she was surrounded by clothes arranged on racks like curtains at the entrance to her stall, with mounds of clothes in the corners. When she started out as a clothing reseller, she bought pieces individually from friends and other vendors, eventually saving up her earnings to purchase a bale from a local importer.

When she cut it open, she found that the vast majority of the tops were soiled and torn, completely unsellable. It was a huge loss.

“When I bought my first bale, I immediately went into debt,” she said.

Janet faced a difficult decision. She had spent her capital on what amounted to little more than garbage, a story that mirrored the man in the Australian broadcast Alison had shown me. If Janet walked away, she would have to start all over again, selling individual secondhand pieces, which wouldn’t produce enough income to replace what she’d lost. Instead, she decided to try her luck again, taking out a loan with 30% interest to buy another bale.

“The second bale, also not good,” she recalled. Now she was stuck with 200 pounds of unsellable clothing, hoping to pluck out a few passable items to try to recoup some of her losses.

What had seemed like a path out of poverty for Janet had become a debt trap. A single mother, she was worried about how she would support her children and her relatives still living in the eastern region of the country. “I hardly have a relationship with my distant family,” she explained, “because I have nothing to send back.”

Like many vendors I spoke with, Janet felt the walls were closing in. She was still stuck with “a debt always carried,” she said, years after her first bad bale. Every week, she had to pay 450 cedis toward the interest on her loans. “No negotiations.” In order to raise the funds, she sold more clothes, which meant buying more bales that cost between 1,000 and 1,500 cedis — on more credit — from the same importer. The price of the bales was always increasing, but her customers balked at paying more when they felt the quality had worsened.

Janet’s friend, Abene, had been in business for 13 years and had a stall just a few feet away. Abene is a stout woman with braids and an easy laugh. Her husband works in South Africa, sending money home while she raises their family on the outskirts of Accra. To get to the market, she commutes by bus for at least an hour each way. Compared to Janet, she was better off, though her business was also suffering. In a mix of English, pidgin and Ga (the primary language spoken in the south of Ghana), she tracked the long arc of her career.

“Before I could buy more because the quality was good. I was able to circulate everything that I buy,” she said. But now she was buying fewer bales and working fewer days at the market. She had avoided taking out a loan, but her income was becoming erratic.

“Every year we might set up a personal goal or family goal toward education, or health, or infrastructure,” she said. “But then because of how the trade is, you end up moving every money that you have back into business.”

She couldn’t pinpoint a particular year when things started to go bad; rather it was a long decline. The results, however, were obvious to anyone running their fingers over the cloth.

“I just don’t like the trash stuff,” she said, pointing to a pile of clothes separated from her two most recent bales, both from the U.K. “See how worn it is?” she said, holding up a shirt. “If they come in this quality, don’t expect anybody to pay good money for this.”

While I was interviewing Abene in her stall, a hawker walked through the aisle selling purses hanging from his arms. He pressed each woman he passed to buy something, and despite the language barrier, I could tell there was something off about him. Liz stiffened when she saw the hawker. With his back turned, she pointed him out to Abene.

“Do you know him?” she asked.

“No, not really,” Abene said.

“He’s a bad man,” Liz said. Abene looked confused. “He’s violent with women,” Liz added. “He hurts them.”

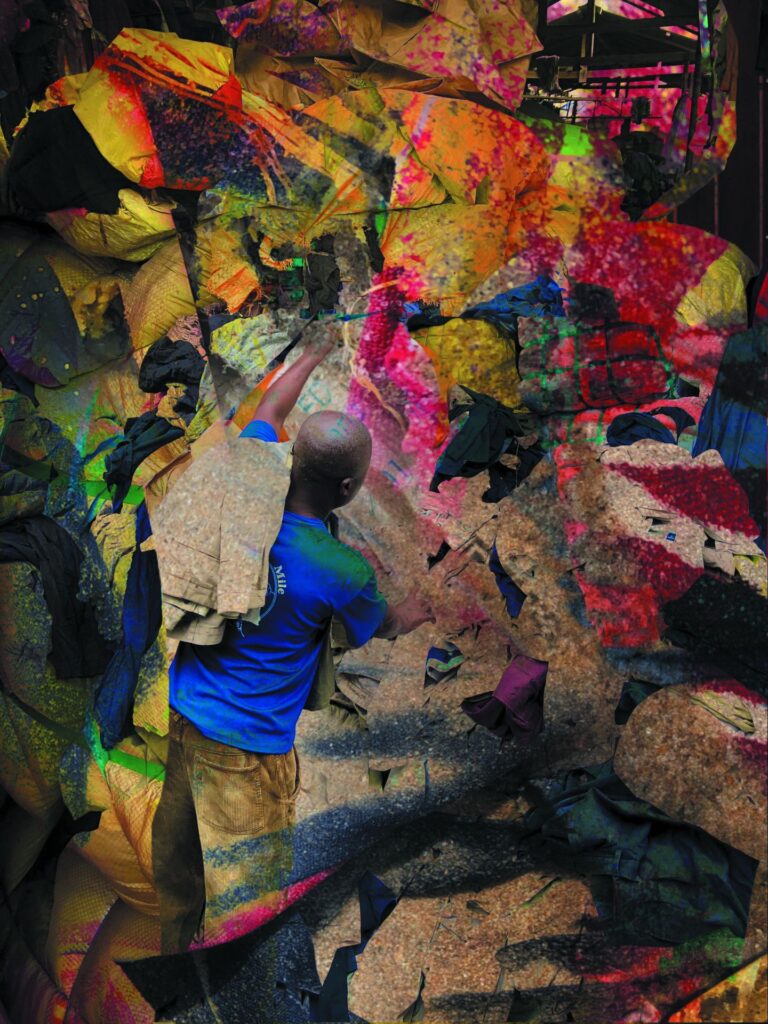

The women Liz was referring to were the market’s head-carrying porters, known collectively as kayayei (the singular form is kayayoo), a term that comes from the Hausa word for “load.” Like many countries in the Global South, Ghana is experiencing a wave of rural-urban migration, fueled in part by climate change. According to research published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health and the African Journal of Social Sciences, thousands of young women leave the northern regions of the country every year in search of work and settle permanently or temporarily in Ghana’s more urban south. The kayayei in Kantamanto come from these regions, traveling by bus or truck to find work in Accra. They leave behind husbands, children and extended families, hoping to send money home. Without skills, education or even the ability to speak the local languages, many wind up working as porters.

In the market hierarchy, kayayei are almost untouchables, meant to stay invisible and silent while taking on the dirty work. Throughout my time in Kantamanto, I kept making the mistake of stepping aside when I saw a young woman struggling to carry a heavy burden on her head, but my instinct to get out of the way threw off the complex choreography of the crowded market aisle. When I stopped short to let a young woman pass, the person behind would crash into me or else have to duck out of the way, sucking their teeth at the ignorant obroni.

One Sunday afternoon, I met with Aisha, the unofficial leader of a local group of kayayei who work at Kantamanto. We arranged to meet at a beach resort a few miles down the coast where nobody from the market would see her talking to a journalist. Near a ramshackle bar and stage were a few tables leading down to a rocky shore. Young couples and groups of friends were photographing each other against the backdrop of palm trees and crashing waves. Aisha approached my table, dressed in a hot pink dress over a long-sleeved shirt printed with hearts, and a maroon headscarf. The combination of her clothes, her girlish laugh and her stiff gait formed a strange impression of a woman who is simultaneously still young yet already pinched with age.

When we met, Aisha was about 30 years old (she doesn’t know her exact date of birth). She was raised in Nyankpala, a village near the northern city of Tamale, and moved to Accra in search of work when she was a teenager, but she got pregnant and returned to Nyankpala, where her grandmother now raises her son. After giving birth, she came back to Accra and began working as a kayayoo, the only work she could find.

The basics of head-carrying are simple, but the terms of employment are complex. The typical kayayoo works on a freelance basis, picking up jobs as they come. Given how many others work in the market, they have little negotiating power over price, and it can be difficult to refuse a job — even when the load they’ve been asked to carry is too heavy. Aisha’s job was more secure than most, she told me. She worked for only one vendor, carrying bales for her customers — who were often resellers themselves — to nearby parts of the city. For carrying a 100-pound bale of secondhand clothing on her head through thronged streets for half a mile, Aisha was paid between 7 and 12 cedis. “If generous, up to 15,” she said. On top of that, her employer paid her 3 cedis from the proceeds of each bale sold. A good day meant earning about 50 cedis; on a bad day, it could be as little as 15. But even on a good day, things could go wrong.

“One of the things I worry about is carrying really heavy loads,” Aisha said. “I tell my sisters against it because the money will never outweigh the consequences.”

In the crowded aisles of the market, I had seen kayayei as young as 12 attempting to hoist 100-pound bales of clothing onto their heads, their skinny legs wobbling under the weight. Head-carrying is common in West Africa, but research shows that carrying heavy loads can lead to spinal compression, vertebrae fractures, paralysis and death.

Even if a kayayoo doesn’t suffer a catastrophic injury, chronic pain from head-carrying is impossible to avoid. “It’s debilitating work,” she said. “Everybody complains about their back, their neck.”

The existence of a kayayoo is precarious, with most women spending the bare minimum in order to send more money home. Many kayayei sleep on the street or in the doorways of buildings near the market. Aisha was splitting a rented, single-room shack near Kantamanto with five other women, whom she referred to as her sisters. They formed a loose family unit, taking care of each other as best they could, but ultimately each was responsible for herself.

Aisha talked me through her routine. Monday through Saturday, Aisha and the other women woke at dawn. There is no running water in the narrow lanes of Old Fadama, where she lives, so every morning, she had to buy a bucket of water to use for her shower. After washing up, Aisha attended prayer at her local mosque, ate a quick breakfast of porridge and was at Kantamanto when the gates opened at 6 a.m.

The high cost of necessities made it harder to send home remittances, the reason she was working so far from her family in the first place. “It’s not enough,” she said. “Last week, I sent my mother 100 [cedis]. I got a call that she needed more, but I don’t have any.”

Every day, Aisha lived with the fear of injury and the awareness that there was always another girl to take her place. The people working in Kantamanto are as replaceable as the clothes they haul. Each morning, buses arrive at Accra’s stations full of desperate young women from the rural north, driven by failing farms and the lack of job prospects in their home villages. “As more have come, they see us as a disposable tool,” Aisha said. “Customers treat kayayei as machines, almost subhuman.”

In the idyllic setting by the ocean, the harsh reality of Aisha’s life seemed even starker. The waves lapped against the shore and the music wafted through the palm fronds, the container ships always visible on the horizon. Tomorrow she would be back at the market, hoisting those bales on her head.

New bales of clothes arrive at Kantamanto every day, but what happens to the clothes that aren’t sold? This was a question I kept asking as I wandered the market. The sheer abundance of stuff for sale at Kantamanto was far greater than the local population could absorb. In the heat of the afternoon, with few customers interested in buying, vendors listlessly dozed on piles of out of season coats and sweaters as if they were beanbag chairs. As I navigated the cramped aisles of the market, I was forced to step on discarded garments that had been tossed on the floor, presumably headed to the dump.

The city’s sanitation system absorbs 3,000 metric tons of solid waste every day, with capacity to absorb 70 metric tons of clothing waste specifically from Kantamanto. Until recently, most of this waste was trucked to Kpone, a 40-acre, state-of-the-art landfill on the city’s outskirts (paid for with a loan from the World Bank). Opened in 2013, it was designed to handle the estimated 1.5 pounds of solid waste each citizen of Accra produces daily. By comparison, the average American produces 4.5 pounds of trash every day. But in 2019, a massive fire broke out in Kpone and the landfill was shut, four years ahead of schedule.

The fire was a predictable consequence of too much textile waste from Kantamanto. Landfills are designed to absorb a mix of garbage, and only in certain proportions. When that balance is thrown off, flammable material and the methane from rotting organic matter combust. Conditions are now too dangerous to continue dumping there, so Accra Metropolitan Assembly is having to truck its waste to improvised dumps alongside the landfill or to a handful of dumps farther from the city. Garbage from the market is now mostly disposed of by private contractors, who are paid to make the clothes that nobody wants disappear. Some are dumped in waterways or washed into sewers during storms, others are chucked in old quarries or burned with other trash and electronic waste.

Outside the Total gas station on Hansen Road, I met up with a researcher from the University of Ghana named Kofi. In his car were two large coolers full of glass containers the size of beer growlers. He was there to take samples of water running from the Odaw River into Korle Lagoon, which empties into the Gulf of Guinea. On one side of the lagoon is Old Fadama, and on the other is an infamous dump for electronic waste called Agbogbloshie, where we were standing. Traditionally, the Korle Lagoon is considered a holy site by the Ga people, the ethnic tribe who founded Accra. Today, the lagoon is a turbid creek, bordered by Kantamanto to the north.

“There’s no doubt that this place is one of the most polluted places on Earth,” Kofi said. “So it’s a good place to sample for any contaminants.”

To get to the lagoon, we crossed a desolate expanse dotted with figures tending fires. One man was sprawled on a mound of trash, his face turned to the hot sun. A kayayoo was curled in a tight ball, sleeping in her carrying bowl. Dotted throughout were small crowds around fires. Clouds of thick black smoke swirled in the air. The smell at the dumpsite was like death itself — not the funk of putrefying organic matter, but the metallic tang of toxic ash mixed with burning plastic. Even through two face masks, I could taste it in the back of my throat and feel it in my chest, an atmosphere inimical to life. And yet life persists there. Gray-skinned cows with bulging humps stumbled through the clothes and other trash to find a patch of vegetation. White seabirds gathered along the water’s edge, and a black-and-white pied crow coasted over the lagoon on the limpid breeze.

“A lot of burning that goes on here is to retrieve scrap metal,” Kofi explained. “So all these things are leaching into the sediment. And when it rains, all those become runoff and get into the water, and bind to microplastics. And the fumes also join the air in the atmosphere.”

When we reached a suitable spot near the bank of the lagoon, Kofi directed the sample collection. He had not brought his rain boots, so his assistant volunteered to clamber down to the river bank with the glass containers, taking off his flip-flops and using his bare feet to get a better grip in the sludge. Kofi described the process and supervised his assistant, occasionally pausing so he could replace an empty vessel with one full of cloudy liquid. The water had to be collected in glass jugs to prevent cross-contamination, he explained. In the lab, Kofi would filter out the sediment and particulates and examine them under a microscope to classify them by type: plastic fragments, microplastics, plastic threads, plastic beads and, of course, plastic microfibers shed by the discarded clothing.

A few miles down the coastline from the sludge of Korle Lagoon I stood amid tangled garments that had washed ashore and become buried in the sand. It was like a giant squid had been stranded yet refused to rot. I was there with activist and oceanographer Richmond Kennedy Quarcoo, who goes by the name Legacy. A thin man with dreadlocks, aviator sunglasses and a laid-back demeanor that belied his passion, Legacy had seen the effects of clothing pollution firsthand.

The beach belonged to a local maritime academy, where Legacy teaches and had once been a student. Though he used to swim in these waters, now signs warn students to stay away from what was in effect a fashion graveyard. Clothes from around the world are scattered and partially submerged, compacted by the tide. Through his nonprofit, Plastics Punch, Legacy leads community beach cleanups on a monthly basis, but he knows it’s a losing battle. “We are very much aware that a beach cleanup in itself is not a solution,” he admitted, “because the trash is going to come anyway after the next high tide.”

We gingerly stepped through the tangles of debris, making our way to the water’s edge. Many of the clothes had reached a state of semi-decomposition, but others had tags I could still read: Hanes, Nike, Adidas, Primark, Topshop, Shein, Pretty Little Thing, Next. I recalled the two trash bags’ worth of clothing I had brought to my local thrift store when I moved from New York to the U.K. and wondered whether any of those old sweaters and shirts and jeans had washed up on this distant shore.

Unfortunately, it won’t be easy to end the influx of secondhand clothing — and not only because the thousands who earn their living at Kantamanto would be left jobless. This trade relationship is as deeply entrenched as the tangled clothing I saw stuck in the sand. As geography lecturer Andrew Brooks explains in his book “Clothing Poverty,” when African countries faced foreign debt crises in the 1980s, they were forced to liberalize their trade policies as a condition of new loans. Unable to compete with a flood of cheap foreign imports, local production fell by an estimated 80%.

Other countries have failed to end the flow of secondhand clothes because of political pushback from the Global North. In 2018, the government of Rwanda declared its intention to ban secondhand clothing imports. To protect American exporter profits, the Trump administration countered by suspending Rwanda’s right to export clothing duty-free to the United States. And when Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda attempted to increase duties to favor local fashion production over secondhand imports, the Trump administration threatened to end their financial benefits through the African Growth and Opportunity Act.

Under pressure from the U.S., the African ban on secondhand clothing imports was put on indefinite pause, but then, in September 2023, Uganda suddenly revived it. “I have declared a war on secondhand clothes to promote African wear,” Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, announced at a press conference. “We will not allow secondhand clothes to enter the country anymore.”

Back at the beach in Tema, Legacy was also in favor of a ban.

“Because most of these things that come is trash, we should not be afraid to ban it,” he said.

Legacy was speaking from a place of experience. He had discovered his passion for marine biology here, but now the animals were disappearing because of the textile waste.

“The sad thing about this beach is it is a turtle nesting beach,” he said. Leatherbacks and Olive Ridley turtles used to come here to lay their eggs, and still do on occasion — after volunteers from Plastic Punch have put in a weekend of grueling work gathering the trash. But the hatchlings usually become trapped in the debris and die before they can make it to the water. The tangles of clothing are too heavy to dig up, but bringing in a tractor to remove them could destroy what little remains of this fragile ecosystem.

“To be frank, it breaks my heart every time I come to the beaches where we work,” Legacy said, his voice cracking. Blessed with a warm climate and a beautiful coastline, Ghana could easily become a destination for ecotourism, he argued, but if these places are spoiled, it will be almost impossible to bring them back. “If things continue the way they are, we have no future for our coastline,” he said.

A man dressed in a red sweater with a fringed hood slouched down the runway, hand in hand with a woman in pleated black and gold pants with a matching top. Behind them came a pair of men in patchwork blazers and another young man in an embroidered denim jumpsuit, who jutted his hip to the side when he hit his mark on the stage. Each model wore the vacant, haughty expression native to fashion runways. But this wasn’t Paris or Milan; it was Obroni Wawu Dripfest, a celebration of upcycled clothing, held for the first time in Shoesellers’ Alley at Kantamanto Market.

Out came another model, to roars of approval from the crowd. He was dressed in a massive pair of patchwork denim trousers, belted and hiked up to his bare nipples. His hair was bleached blond, his face obscured by wraparound sunglasses. This, I gathered, was the designer.

In recent years, fashion activists and influencers in Europe and the U.S. have tried to make the month of September #SecondhandSeptember to celebrate wearing and buying old clothes instead of new ones. Many of these online posts involve influencers flaunting items purchased from eBay paired with designer pieces from last season. Captions encourage followers to “shop your closets.” These efforts are commendable — at least when compared with “Shein haul” videos. But to the people who work at Kantamanto, secondhand September is absurd; every day is secondhand September. This was the inspiration for a recent festival put on by Kantamanto’s vendors in collaboration with The Or Foundation: a festival they called “Obroni Wawu October” or “Dead White Men’s Clothes October.”

Taking over Shoesellers’ Alley, where I had watched Petee conduct his early morning fire sale, the event was a kind of street party to celebrate the labor and creativity of the people who work at Kantamanto — paid for, in part, through the donation from Shein. Kebabs sizzled on grills, music blasted from the sound system and later in the evening there was a so-called drip contest for people to show off their most elaborate outfits sourced from secondhand bales. The event brought together vendors and tailors who work at the market, along with the younger generation of resellers and upcyclers who increasingly represent the future of Kantamanto. This relationship is an uneasy one; the resellers use their knowledge of trends to buy pieces cheaply and flip them online, while the people who buy the bales often get stuck with the junk. But many of the young resellers at Kantamanto view the resale business as a temporary stopping place on the way to bigger dreams.

Among them was the young man with the bleached hair who had led his pack of frowning models, known as Lucky Blezz. His given name is Anafo, though his clients also call him “the world plug,” a guy so connected he can source anything on Earth.

Anafo grew up in the impoverished northeastern town of Bolgatanga, which has a long tradition of basket weaving from a local plant called elephant grass. As a child, his family taught him to sew, and with a dream of somehow breaking into fashion, he came to Accra in search of work. He started as a roadside seller and slowly built up a secondhand business in Kantamanto. When a local musician asked him to find him some outfits for a video shoot, “I said, ‘This be the day,’” Anafo recalled. Ever since, he’s been styling, modeling and designing his own clothes from what he finds at Kantamanto and sourcing vintage pieces for clients he connects with through Instagram and TikTok.

Later that evening, the Ghanaian Afrobeat singer, Kelvyn Boy, who discovered Anafo all those years ago, introduced his friend on stage:

“The big designers, Gucci and this, they started like this, you understand? Louis Vuitton, they started like this.”

It wasn’t far from the truth: Guccio Gucci began his business as an independent leather craftsman in Florence; Louis Vuitton was an orphan who got a lucky break making trunks for Napoleon III’s wife. A lot has changed since the 19th century, but the biographies of luxury fashion’s two biggest names aren’t so different from Anafo’s.

On Instagram, Anafo confidently poses in outre, high-fashion looks against colorful backdrops or out and about on the streets of Accra. In one series he’s leaning against the lever of a hand-pumped water well, wearing a voluminous pair of patchwork bell-bottoms of his own design. The image encapsulates the strange contradictions of a place like Ghana. Kantamanto is home to a vibrant and creative community of artisans who are “plugged” into the global fashion conversation, but they are largely excluded from the global market — with trade barriers, travel restrictions, and logistics making it extremely difficult to sell their designs abroad. Given the right opportunities, it wouldn’t surprise me if Anafo reached the same heights as Gucci or Louis Vuitton, but perhaps we should ask whether such heights can or even should be scaled again. Why seek to replicate a broken fashion system based on chronic overproduction when you could build something new?

Months after I had returned to the U.K., I decided to check in on the people I’d met at Kantamanto. Since I had left Ghana, The Or Foundation had opened a new headquarters, and in a video published in 2022, I could see employees were cutting and sewing tea towels for the Ghana Food Movement from old T-shirts. Scraps were being fed into a mechanical shredding machine to create “reroll,” a kind of shoddy fabric. About 100 kayayei from the market have been given chiropractic treatment and diverted into a job apprenticeship program, with outposts set up in the northern city of Tamale to help women return to their hometowns. Among them is Aisha, who is now living with her family. The women’s blouse sellers I’d met at the market, Janet and Abene, are now both working for The Or Foundation, too, helping to conduct surveys of vendors and distribute emergency relief funds. In November 2022, a fire broke out in the tailors’ section of the market, destroying thousands of bales. It was not the first fire at Kantamanto, nor is it likely to be the last; perusing the cramped aisles, I had seen vendors plug fans into jerry-rigged electrical outlets and pressers heat up heavy clothes irons over open grills.

In a place like this, fires, floods, droughts, and toxic air and water are thought of less as preventable tragedies than as facts of life or acts of god. The flow of secondhand clothing into the market continues unabated, though perhaps with less certainty than before. Driven by the twin crises of debt and inflation, importers are facing rising costs. This trend may create an opening for local clothing production and upcycling, or it may further impoverish the people who are most vulnerable. Extended producer responsibility legislation is coming into effect, and with it — many hope — funding from Europe and the U.K. But even if this money trickles down to the places that deal with the consequences of so much consumption and pays for upgraded infrastructure at the market and landfill, it could not do so quickly enough for the people on the ground or at the scale required to fix the damage already done.

Wandering the aisles of Kantamanto and meeting the people who work there, I was struck by their perseverance and ingenuity. Long ago, they figured out how to revive things that people in the Global North had thrown in the trash; how to cut and sew and embellish what they have at hand to make a garment greater than the sum of its tattered parts. But there is no more room at the dump, and the seas are full of clothes. The people of Kantamanto can no longer carry the burden of other people’s waste.

Reporting for this story was funded by the McGraw Center for Business Journalism.

This article was published in the Fall 2023 issue of New Lines’ print edition.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.