On the road to Gaza, our van cut through the stunning north Sinai desert, passing at least six Egyptian military checkpoints along the way. It was Jan. 8, 2024, three months after the start of the war. We passed through oases lush with palm trees, their greenery a striking contrast to the arid landscape. At each stop, guards meticulously inspected our dozen bags full of medical supplies and insulin before waving us through. We departed Cairo at sunrise, finally arriving at the Egyptian side of Rafah after an exhausting eight-hour journey, just as the sun began dipping below the distant horizon.

Over the past 15 years, I have undertaken at least 40 medical missions — to Syria, Greece, Bangladesh, Ukraine, Lebanon, Yemen, Colombia and Puerto Rico. This was my fourth mission to Gaza, but it was very different from the first three. In Syria, I worked in underground hospitals, resuscitated victims of barrel bombs and missiles, treated countless refugees fleeing war and mass atrocities, and trained doctors on how to protect themselves from chemical weapons. The faces of children traumatized by wars and displacement remain seared into my memory. Some nights, I wake screaming. I believed I had seen the worst humanity could inflict.

Until Gaza.

The first four months of the war were beyond catastrophe. It was the making of another Nakba: civilians and children murdered en masse, besieged populations forcibly displaced, a health care system systematically dismantled, humanitarian aid weaponized, an entire people pushed to the edge of survival.

We have seen this in other wars — but not at such scale. This is not merely a humanitarian crisis; it is a test of our collective conscience. The horrors I witnessed in Syria — siege tactics, hospitals under attack, civilians targeted — have been repeated in Gaza with chilling impunity: a total war waged not just against people, but against health care, education and every foundation that sustains life in the territory.

We embarked on this medical mission to offer more than aid; we came to stand in solidarity with our Palestinian colleagues and to bear witness. Though local doctors are the backbone of their community’s health care, the war has overwhelmed them. Our task is to lend an extra hand, providing a moment of respite and extending care to the traumatized. But our ultimate responsibility is to ensure their story is not forgotten — to sear the raw truth of their resilience into the world’s conscience and force the powerful to see.

During my previous missions to Gaza, I came to know many local physicians as I traveled throughout the narrow coastal territory. Contrary to public perception, Gaza is beautiful and remarkably diverse. I found its people welcoming and generous despite enduring years of blockade and conflict. I immersed myself in the region’s history, visiting museums, historic mosques and churches, and savoring its delicious cuisine. I learned that Gaza exports flowers and strawberries to Europe using innovative irrigation techniques.

Gaza’s medical community impressed me deeply. Doctors maintained up-to-date knowledge, absorbing training like sponges. The health care system included 38 hospitals. The Al-Shifa Medical Complex, Gaza’s largest facility, served as a tertiary center and Level 1 trauma center — not unlike my own hospital, Advocate Christ Medical Center in Chicago, where I am a pulmonary and critical care specialist. It provided health care to 750,000 patients annually, performing 25,000 complex surgeries and 70,000 dialysis sessions. Gaza boasted some of the Middle East and North Africa region’s highest literacy and vaccination rates, a point of pride for local physicians. Despite its small size, the territory had 12 universities serving 2.1 million people. Many young Gazans held multiple degrees but faced unemployment due to the blockade and lack of opportunities.

On one mission, I met Dr. Hussam Abu Safiya, a pediatrician in Beit Lahia in northern Gaza. Trained in Kazakhstan, he returned home to Gaza to establish an intensive care unit at Kamal Adwan Hospital, determined to prevent children from dying by providing emergency treatment during the “golden hour” while they awaited transfer to Al-Shifa. We equipped his unit with neonatal ventilators, monitors and incubators. He was offered positions in the Gulf, but he refused to leave his community. He took pride in his hospital’s progress, frequently sharing updates on Facebook about medical advancements.

In January 2025, my organization, MedGlobal, organized a medical mission as part of the Emergency Medical Teams initiative led by the World Health Organization (WHO), an effort to support local physicians and fill the gaps created by the ongoing war in Gaza. We were among the first medical teams allowed into Gaza after Oct. 7, 2023.

Hundreds of trucks lined both sides of the road. “Those are food trucks waiting to enter Gaza,” our driver muttered. “Some have been waiting for weeks.”

After two hours of rigorous inspections at the Egyptian border crossing, we finally received clearance to enter Gaza. We hugged every member of our local team. They had been waiting patiently for hours. Their eyes were filled with emotion as we embraced and loaded our supplies into two vans. “Welcome to Gaza,” Rajaa said. “Hamdillah al salameh [Thank God for your safety].”

The drive from the border to our guesthouse in Mawasi Rafah, near the Mediterranean Sea, felt like entering a dystopian universe — a landscape of endless tents stretching through lightless streets beneath a sky heavy with despair. More than a million civilians had been forced into Rafah, a city that held only 300,000 people before the war, as fighting continued in the north.

“The war is now in Khan Younis, just 9 kilometers [5.6 miles] from our house,” whispered Fatma, our program officer, who was displaced from Gaza City with her family, as was Rajaa. I glanced at the weary faces of my colleagues; they kept silent, stunned by the devastation and suffering surrounding us.

“We’re so happy to see you,” Fatma said. “Do you think we will have a ceasefire soon?”

“Inshallah [God willing],” I replied.

From the first night, the war raged dangerously close around us, unfolding before our eyes. We could hear the bombs — the roar of Israeli fighter jets, the thumping of helicopters, the explosions of missiles and the distant thunder of warships. We witnessed the impact of all of that in the hospital in one mass casualty event after another. At night, missiles lit up the sky, their impacts shaking the ground. The first night, I couldn’t sleep. Eventually, I grew numb to the chaos. People moved through crowded streets as if this were normal. It wasn’t. Dark smoke rose incessantly on the horizon while drones buzzed overhead around the clock, their persistent whine creeping under your skin.

By the time we arrived, Gaza had been devastated. Thousands had been killed, including 12,000 children, and more than 80,000 were injured. Half of them had severe injuries that required multiple surgeries and tended to develop drug-resistant infections that can lead to death. There were 4,000 new amputees. Vaccination rates dropped from 95% to 70%. There were outbreaks of measles and other preventable infections.

Already in January of 2024, a third of the hospitals had been destroyed, besieged or deserted, including Al-Shifa. It was near impossible to reach northern Gaza. About 400 local health care workers had been killed, including 65 doctors, 105 nurses and 121 paramedics. Another hundred health care workers were detained. Attacks on hospitals and health care workers have become tragically common in Gaza, as they were in Syria and Ukraine — another grim norm of modern warfare, like the targeting of civilians. Each assault on medical facilities constitutes a war crime under international humanitarian law. Yet without accountability, these violations continue with impunity, eroding both medical neutrality and health care systems themselves.

At the time, Rafah was the main point of access to the rest of Gaza for food, water and medicine. There were three barely functioning hospitals, with only two CT scanners, and one birth center serving more than 1.3 million people. There was a shortage of many lifesaving medications, including insulin, and a shortage of doctors, hospital beds, dialysis units, ventilators and medical supplies.

In war zones, patients with acute conditions — severe bleeding, heart attacks or pulmonary embolisms — die without access to emergency care. Meanwhile, those with chronic illnesses like heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease suffer in silence, their conditions worsening without physicians or clinics. These victims may never appear in casualty counts, but they are casualties of war, nonetheless. Crowding in tents and shelters also causes outbreaks of scabies, lice and intestinal and respiratory infections.

In the first week, I was assigned to work at a newly established makeshift polyclinic in Rafah. On the morning of our clinic’s opening, I prepared myself mentally for dozens of patients. As I entered the prefabricated structure that would serve as our medical center, I found myself wading through a human tide — mothers clutching listless children, elderly men leaning on younger relatives, entire families waiting silently in the dust. By sunset, our exhausted team had logged over 700 consultations.

One of my patients on the first day was Sarah, a 14-year-old teenager, who was displaced from Sheikh Radwan, a neighborhood in Gaza City that was completely leveled by bombs and missiles. She missed her school and friends. She lived with her parents and five brothers and sisters in a small tent surrounded by hundreds of other tents. She dared not go to the washroom at night. There was one latrine for every 200 people in the camp.

Sarah had jaundice, fatigue, fever, nausea and abdominal pain. After a physical examination, I diagnosed her with hepatitis A and dehydration. In the absence of laboratory tests to confirm the diagnosis, it felt as though I had been transported back to the Middle Ages, where diagnoses relied solely on unaided clinical assessment. This is what the collapse of the health care system looks like as a result of the war and humanitarian blockade.

At that time, the WHO reported approximately 8,000 cases of hepatitis A in Gaza, primarily due to water contamination from seeping sewage. Our medical team administered intravenous fluids to Sarah. Her heart rate improved gradually. The following day, Sarah returned to the clinic accompanied by her parents, her face beaming with a big smile.

I saw Ahmed, a construction worker. He told me that his 15-year-old nephew bled to death at Al-Ahli Hospital, where only two surgeons remained. “I’m tired of rebuilding,” he said. “There’s no life left here.”

The next day, I treated a 24-year-old asthmatic woman using a hand-held nebulizer I had brought from Chicago. For 20 days, she had suffered from shortness of breath, coughing and wheezing in her tent. Her asthma had flared up due to the cold weather and from burning wood to heat the tent. After receiving a simple bronchodilator treatment, she took her first deep breath in weeks.

Everyone in the clinic had a tragic story. My nurse, Bisan, told me while changing bandages, “I wanted to be a photographer, then I became a nurse because Gaza needs nurses. Now I just hope to see tomorrow.”

Dr. Rachid Al-Qanoue, a pediatrician from Jabalia, now lives in a classroom-turned-shelter at Rafah’s Fadila School with 50 displaced family members. Ten of his relatives were killed when his neighborhood was bombed. Despite this, he runs a MedGlobal medical point in the school (a makeshift primary health center whose doctors and nurses — themselves also displaced — provide care to the displaced), treating 180 patients daily and performing 40 wound dressings with the help of two nurses — often without anesthesia. He uses vinegar as a disinfectant. As I entered, he was changing the dressing of one of his patients — 12-year-old Abdallah, who lost his right eye and suffered shrapnel wounds while collecting firewood. He was transported to the clinic by donkey cart. Abdallah clenched his teeth, stifling screams as Al-Qanoue worked. “We don’t have lidocaine,” he explained.

In one of the classrooms converted to a shelter at the same school, I visited Dr. Tahreer, an obstetrician who had also been displaced with her family. She had just undergone a cesarean section the day before. Proudly, she showed me her beautiful newborn, Mahmoud. I held him gently and kissed his head. The cramped room housed dozens of other women and children sharing the same space.

The following week, I was assigned to work in the ICU at Nasser Hospital, a remarkable medical complex in Khan Younis. Having worked there in 2019, I had helped train local physicians to use portable ultrasound devices — small units that connect to smartphones and transform them into Doppler screens. This technology enables physicians to diagnose life-threatening internal bleeding in trauma patients and make critical bedside decisions that can save lives.

Over the years, we’ve donated dozens of these devices to several hospitals and conducted multiple training missions. We’ve implemented similar programs in Ukraine, Syria and Yemen. These portable devices prove invaluable during wars and disasters, particularly in resource-limited settings. The “train-the-trainer” model, a proven approach in global health, ensures sustainable impact by building local capacity within communities.

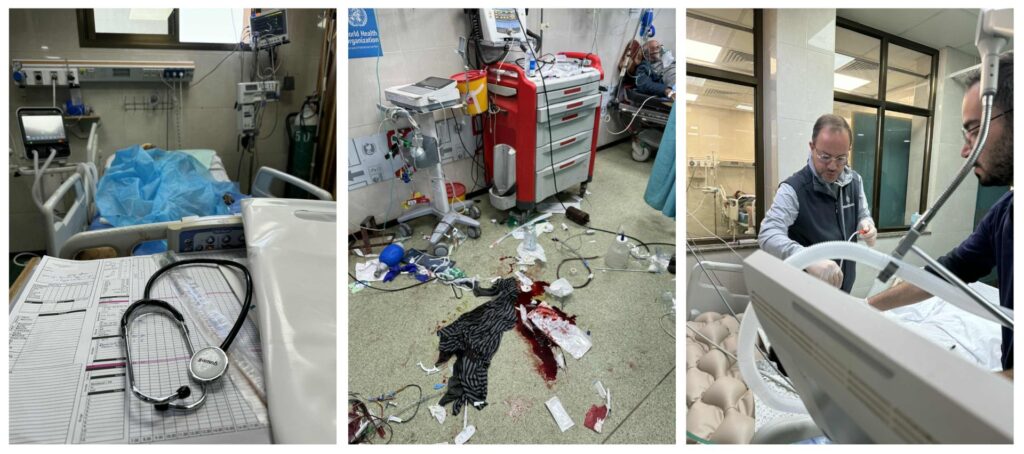

When I visited the hospital, I could not recognize it. It was devastated by the war, like Gaza’s civilians themselves. Sixty percent of its routine services were suspended, including pediatric dialysis and cancer care. Twenty-eight renal patients died due to lack of dialysis. Its neonatal ICU was converted to a mass casualty triage area. Its staff had no salaries for four months.

I looked out the window in the hallway, near the ICU, and saw dark smoke rising from some of the buildings east of the city. The Israeli military was closing in. The war was coming to the hospital. Doctors were worried that the Israeli army would besiege the hospital, humiliating the doctors the same way they did in Al-Shifa. “I prefer to be killed by them than to be stripped naked in front of my colleagues,” one doctor told me. The story of one of the most senior doctors in Gaza, who was humiliated during the siege of Al-Shifa, circulated. He went into a severe depression after that incident and did not return to work.

The ICU was overflowing with young trauma patients — half of them children, many suffering from postoperative complications. Some battled relentless infections, others bore severe burns. The Israeli military has rendered Gaza’s only burn unit, at Al-Shifa, nonfunctioning. Though we had broad-spectrum antibiotics, the absence of culture and sensitivity tests (tests that identify the specific bacteria causing an infection and determine the most effective antibiotic to treat it) left us blind, unable to identify the exact pathogens or tailor treatment. The consequence? A resurgence of multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR), dooming patients to sepsis and multiple organ failure. MDR is identified by the WHO as one of the most dangerous global health problems.

Every patient was emaciated, severely malnourished from a lack of enteral feeding, further crippling their immune systems and leaving them defenseless against infection. Surviving the bombs offered no guarantee; even those who made it through surgery often succumbed to infection and malnutrition. A handful of patients lingered on a waiting list of 6,000, awaiting evacuation. Nasser’s young doctors — extraordinarily skilled and tirelessly dedicated — remained focused on their patients despite unbearable stress and crippling shortages. I didn’t feel my expertise was needed in the unit, except to give the exhausted doctors some breathing room.

As I left the hospital on my second day, loud screams came from the emergency room entrance. I rushed to find complete chaos — people carrying bloodied children and adults, ambulances arriving nonstop, families wailing in despair. Thirty-eight wounded flooded in; seven were dead on arrival. An Israeli shell had struck a nearby aid distribution center, I was told.

I stayed to help. The trauma room floor was covered with patients and blood. Young doctors clustered around one victim, using a portable ultrasound to check for internal bleeding — a technique we’d trained them on years earlier. Nearby, a physician intubated Khalil, an unconscious 12-year-old child with head trauma and abdominal shrapnel wounds on the floor. After a brief ultrasound test that confirmed bleeding around the liver, Khalil was rushed to surgery.

Without anesthesia (none remained), I inserted chest tubes into two children. They were comatose. These conditions would be unthinkable in the U.S. — in Gaza during the war, they are the norm.

At my Chicago hospital — a Level 1 trauma center with abundant resources — mass casualties trigger an impeccably coordinated response. The emergency room transforms into a triage theater where every trauma surgeon, resident and nurse mobilizes instantly. They stabilize patients in minutes: Bedside ultrasounds diagnose internal bleeding, elevators whisk them to operating rooms and anesthesia guarantees pain-free procedures. No gasping child pinned to the floor. No screaming through unmedicated chest tubes. Here, chaos never overcomes care, and no life slips through the cracks.

The next morning, I rushed to the ICU to check on Khalil. He was brain-dead, but still on life support, because his head injury was so severe. With communication services down, we couldn’t call his family. The doctor signed his death certificate. His body was sent to the morgue. I took a picture of the death certificate — one among thousands, evidence for the media and U.S. President Joe Biden, who doubted Gaza’s child casualties.

Our team worked in three hospitals: Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir al-Balah, Al-Najjar Hospital in Rafah and Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis. Contrary to Israeli accusations, we witnessed no evidence of militarization — no Hamas operatives, no gunfire originating from hospital grounds, no weapons, no restricted sections and no tunnel entrances. Clear signage at all entrances explicitly stated: “No weapons permitted.”

I asked both local and visiting physicians, and they all said the same thing: There were absolutely no military or Hamas activities conducted within Gaza’s health care facilities.

As our medical delegation boarded the plane back from Cairo, we carried not only the weight of what we had witnessed but also the urgency about conveying it to those with the power to act. One month after the mission, I joined a delegation of physicians in Washington to share our firsthand experiences with policymakers. Our delegation met with officials across the U.S. government, from the Department of Defense to the State Department and the White House National Security Council.

On Capitol Hill, we met with Sens. Bernie Sanders, Chris Van Hollen and Peter Welch, as well as staff for Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries. Sanders, visibly moved, later echoed our accounts in a Senate speech.

We also met with USAID Administrator Samantha Power and her team. I got to know them very closely during the Syrian crisis. She was very helpful. We were surprised by her knowledge of every detail about the humanitarian situation in Gaza. She asked probing questions and projected empathy. She was clearly conflicted. My sense was that she was working hard to assert her humanitarian point of view within the administration but becoming frustrated by the resistance to changing course and to holding the Israelis accountable.

Between meetings, we raced to interviews — CNN, MSNBC, The Washington Post, NPR and The Guardian — each platform amplifying Gaza’s suffering to different audiences. At the United Nations Correspondents Association press conference, reporters called it “the most compelling briefing in years.”

Everyone told us that Biden faced a pivotal choice over whether to certify that Israel was complying with international humanitarian law in its use of U.S. weapons. Our delegation’s accounts — of sniper fire wounds in children, of blocking lifesaving aid into Gaza, of amputations without anesthesia — challenged that narrative. We left Washington exhausted but resolved. Advocacy is slow, but silence is complicity.

On April 3, 2024, I walked into the White House West Wing with a weight I could barely carry — the voices of Gaza’s doctors, the faces of children I couldn’t save and the pleas of colleagues begging the world to stop the war. I had promised them I would be heard at the highest level, no matter how hard it was.

Many in my community urged me not to go. Outraged by U.S. policy, they called Biden “Genocide Joe,” blaming him for enabling Israel’s war. But I went anyway — not as a politician or activist, but as an eyewitness, as a humanitarian, as someone who had seen too much suffering to stay silent.

The room was heavy with silence. Around the table sat Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, national security adviser Jake Sullivan and U.N. Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield. My colleagues from MedGlobal were with me.

Dr. Thaer Ahmad, a young Palestinian-American emergency medicine physician, spoke first, his voice breaking as he described the agony of Palestinian families, and his own trauma. Overcome by emotion, he asked to step out. The president nodded quietly — he understood.

Then it was my turn.

I thanked Biden for the meeting but did not mince words. I showed him two photographs — one of 7-year-old Hiyam, who succumbed to third-degree burns after an Israeli strike destroyed her home, and another of 12-year-old Khalil, whom I met amid the carnage at Nasser Hospital. I placed a picture of Khalil’s death certificate in his hands.

“Behind the number — 13,800 dead children — are real faces,” I said. “Real lives.” I invoked the words of Martin Luther King Jr.: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Then I made my demands clear: an immediate ceasefire, no invasion of Rafah, 1,000 aid trucks entering Gaza daily and a Marshall Plan for reconstruction.

I looked him straight in the eyes and said, “President Biden. Your legacy will be defined by your actions in Gaza.” A decade ago, I stood in this West Wing during a Ramadan iftar and delivered the same warning to President Barack Obama regarding his inaction in Syria. This was after returning from Aleppo, where I witnessed firsthand the devastation wrought by barrel bombs, chemical weapons and hospital attacks on Syrian civilians. That crisis spawned a global refugee catastrophe whose consequences reverberated worldwide.

Biden listened. He spoke of Hamas’ atrocities — a mother and child burned alive — but admitted Israel’s response had gone too far. He compared it to America’s “overreaction” after 9/11, invoking his late son Beau, who served in Iraq. He acknowledged Israel had no plan to protect civilians in Rafah and promised to push for more aid. Harris echoed him, emphasizing Palestinian dignity and a political solution.

I waited for the next few weeks to see if our meeting had an impact. But nothing changed. Biden failed to stop the Rafah offensive — the very invasion he vowed to prevent. The city was flattened, including the clinic where I worked. The bombs kept falling, children died of shrapnel and malnutrition, hospitals were attacked and the famine grew worse.

It has been two years since the war began, and 20 months since my medical mission. Israel’s war continues to rage on. The humanitarian situation has become catastrophic — far worse than what I witnessed. Rafah in the south no longer exists; it has been destroyed. Entire cities in the north, including Jabalia, Beit Lahia and Beit Hanoun, have been completely leveled. Only 19 of Gaza’s original 38 hospitals remain partially functional. Most schools and all universities lie in ruins. The gradual destruction of property, resources and livelihoods has left Gaza’s 2.1 million residents without means to survive. Most of the territory is now unlivable.

Health care workers are also bearing the brunt of the war. There have been close to 700 attacks on health care facilities since October 2023, and 1,580 health care workers, including several prominent doctors and surgeons, have been killed. These doctors could not be replaced even if the bombs stopped falling. A U.N. commission of inquiry concluded that “Israel has committed genocide against Palestinians in the Gaza Strip.”

Only 19 of Gaza’s 38 hospitals remain operational, and they are struggling with severe supply shortages, a lack of health workers, persistent insecurity and a surge of casualties, all while staff work in impossible conditions. Of the 19 hospitals, 12 provide a variety of health services, while the rest are only able to provide basic emergency care.

Over 67,000 people, including more than 20,000 children, have been killed, and 169,000 injured in this war. Half of them have moderate to severe injuries, meaning a life of infection, complications, pain, trauma, disability and potential death. Nearly 42,000 of those injuries are life-changing, according to the WHO. And close to 13,000 patients are waiting for evacuation. Close to 90% of the population have been displaced — most of them multiple times.

Gazans are now confined to less than 15% of the land, systematically driven southward in a pattern that bears all the hallmarks of ethnic cleansing. A new evacuation order was recently declared for the central area. Most of Gaza has become a red zone — designated as an active military area where civilians are prohibited, including the neighborhood where our medical director, Dr. Salwa Elteibi, resides. Yet she cannot leave her apartment. “I couldn’t find any other livable space,” she told me during a phone call in August 2025. “We’re exhausted, doctor. People are passing out in the streets from malnutrition and exhaustion.” The desperation in her voice was palpable.

Elteibi lives with 17 family members in a partially destroyed Gaza City apartment. She has lost 40 pounds and has been suffering from intestinal infections due to contaminated water, which is now distributed only once every two weeks. For three months straight, her family has survived on nothing but lentil soup and some pasta. The markets stand empty; even money can’t buy food. “Two pounds of tomatoes cost 100 shekels ($30) and 2 pounds of flour costs $35,” she said. Once a week, she gives each child a single ready-to-use therapeutic food bar wrapped in pita bread. “They’re starving, and I don’t know what to do.” She can’t fight through thousands at the deadly distribution centers for a sack of flour.

People are killed daily by gunfire from Israeli troops or from armed guards outside aid centers — while waiting for food rations or trying to reach one of the four remaining distribution sites in these deadly red zones. Over 1,000 aid-seekers have been slaughtered at what have essentially become killing fields disguised as distribution hubs.

For seven consecutive months since March 2025, Israel has blocked most humanitarian aid. An average of 29 trucks is allowed every day, compared to 500 trucks before the war. During the last ceasefire, which ended in March, around 600 trucks were entering Gaza daily.

Gaza has also seen a sharp rise in severe acute malnutrition and related deaths among children. Up to 50% of severely malnourished children may die without urgent intervention because of low immunity. Simple infections like diarrhea and pneumonia may cause death. They also die from hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances and heart, kidney and liver failure. Even feeding these children is a challenge, because they may die from refeeding syndrome, a medical complication that results from imbalances in the body as a result of returning to normal nutritional support. Those who are lucky enough to survive will have stunted growth as well as irreversible damage to their cognitive functioning and mental and physical health.

Current aid levels are woefully inadequate to prevent more deaths. In July, MedGlobal joined with more than 100 aid groups operating in Gaza — including Amnesty International, the Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE), Doctors Without Borders, Oxfam International and Save the Children — to demand the lifting of Israel’s aid blockade, which is the cause of the mass-starvation crisis.

Gaza’s man-made famine remains entirely preventable. Deliberate blocking and delaying of large-scale food, health and humanitarian aid has cost many lives. The solution is simple: Israel must lift the blockade, allowing more than 1,000 aid trucks daily through land crossings. The U.N. and nongovernmental organizations are ready — with thousands of loaded trucks waiting to deliver lifesaving aid.

After two years of war, blockade and international indifference, Gaza has reached a catastrophic inflection point. While humanitarian and human rights organizations universally condemned the Oct. 7 attacks, nothing justifies the devastation that followed.

Today, I question whether Gaza can still be salvaged. Israel’s military campaign has reduced most of the territory to uninhabitable ruins. With profound sorrow, I fear we may be witnessing its irreversible destruction, though I pray that the resilience of the Palestinian people and Gaza will prove this fear unfounded.

Elteibi sent me a photograph from our stabilization center — her gaunt frame bent over a mother clutching 2-year-old Mohammad. The child, reduced to skin stretched over bone, embodied what 22 months of total war had done to Gaza. In their hollow cheeks and sunken eyes, I saw the same story repeated three times over.

Every member of our local medical team has been impacted by food insecurity. Elteibi’s body had whittled away from relentless hunger and exhaustion. Her last audio message, just five words long, seemed to carry the weight of the entire crisis: “I can’t take it anymore.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.