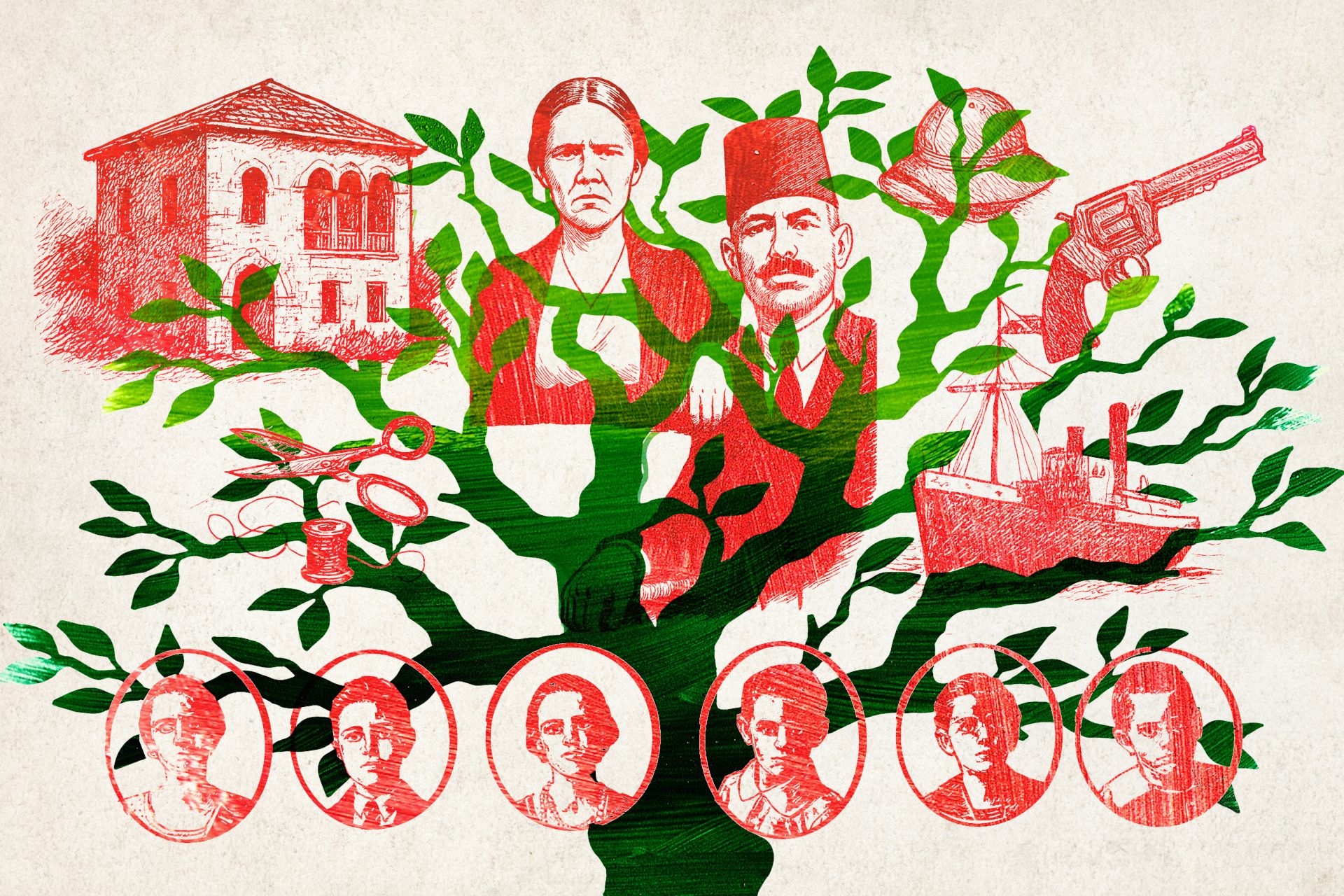

Zabbougha is a tiny village in Lebanon’s mountainous district, or “qada,” of North Metn. The year-round population is roughly 200. It contains one grocery store, three churches and, curiously enough, a tiny wine museum. It is also where my father’s family is from and where I live, in a house that was originally built by my fifth great-grandfather, Mufrij Karam, sometime in the 18th century. But our story starts in the late 1890s, when my grandfather, Esper Karam, was forced to leave the village after he killed a man who had insulted his mother.

Like 130,000 other Lebanese, mostly men, in the final decades of the Ottoman Empire, my grandfather made it to Brazil via the port of Santos, gateway to the province of Sao Paolo. With a fresh start, Esper became “Esperidião.” He established a trading company with Messrs. Domingos and Zacharias, joined the Freemasons, learned Portuguese, and met and then married Elin, a Swedish seamstress who had emigrated from Stockholm with her family in 1891.

Emigration had not been a happy experience for Elin, who became known as Helene. Within months of arriving, her youngest sister, Anna, and her father, Johan, both died from unspecified illnesses. In a letter home to family friends, Elin’s sister Maria describes their new home. “It is impossible for me to express and mention in a letter how everything is here, how different it is in manners and people compared to Sweden. There are carbon-black negroes, brown so-called Mulattoes, Italians, Portuguese, Spaniards, Turks, Germans. The confession here is Catholic. They worship saints and the Virgin Mary; their services and ceremonies are very different from ours.” In a subsequent letter, she is resigned to the finality of the move. “How I long to go to a Swedish church; hear the organ play and listen to Swedish voices singing a hymn, but it will never be. We have no prospects to come home.”

But Elin did get out. In 1915, Esper left Brazil and brought her and their first three children — Selma, Assaf and Irasema — to the house in Zabbougha, just in time to be caught in the dreadful famine, compounded by the Allied navies’ blockade of the port of Beirut during World War I, that ravaged the country for three years.

In Zabbougha, the people were often forced to eat grass to survive; a radish was considered a delicacy. Elin must have wondered what she had done to deserve yet another traumatic upheaval. Yet she did her bit. With her strong Lutheran sense of duty, she took in malnourished children until they were well enough to go back home.

When things improved, there were three more children, all born in the village: another girl, Souria, and two more boys, Nohra and Bechara, my father. Esper was off again, this time to French Sudan, now Mali, where, with his brother, he established trading companies in Koulikoro and Bamako.

By all accounts, it wasn’t the happiest of marriages, and the couple spoke to each other mostly in Portuguese, which was neither’s native tongue. They did, however, have 22 grandchildren born between 1935 and 1965 (Irasema’s son, the late actor Antoine Kerbaj, was the first, and I was the last).

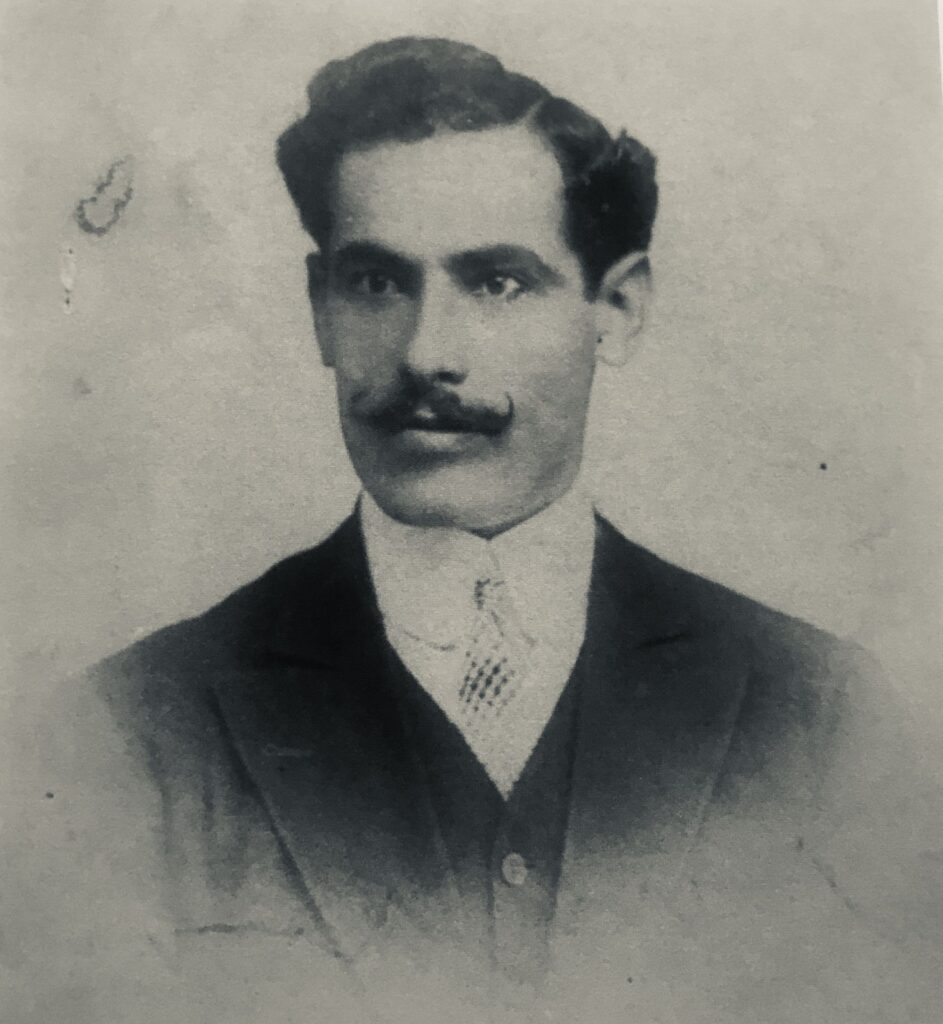

Esper lived by a code of masculinity long since outdated, and is remembered by my older cousins through the rose-tinted lens of nostalgia as either a romantic adventurer or a Lebanese tough, or as a misogynistic curmudgeon who didn’t suffer fools and had little time for children. He was probably a bit of all three.

What is certain, though, is that there were flashes of warmth. “One summer, all the boys had bows and arrows except me,” my sister Randa recalled. “I cried and ‘Jiddu’ [‘Granddad’] Esper made me a set. He said it was to stop me crying, but I think it was also a gesture of genuine affection, and I have to say it was far superior to everyone else’s.”

He died in 1964. He was 86. I was born a year later and there was a half-hearted campaign to name me after him. Elin moved to London to stay with Bechara but didn’t get on with my mother. Most of her later life was spent with her daughter Selma, who never married and who lived in Ras Beirut on Makhoul Street, where she worked, like Elin, as a seamstress.

During Lebanon’s civil war, Elin moved back to the village, padding about the house in a haze of dementia, muttering to herself in a mix of Arabic and Portuguese. She spent her last year in bed, dying in 1977 at 92 in the home in which she had raised her six children. She was buried next to her husband and eldest son.

In 1992, I went down to the “qabu,” or cellar, with my childhood friend, Nagy. The smell, a blend of diesel, vinegar and dried mint, had not changed since I was a young boy, when I would help myself to the keys to look for Esper’s mythical Smith & Wesson revolver, the one with which he was said, rather preposterously, to be able to shoot the eye out of a chicken, and which he had apparently won in a bet with a man from the neighbouring village of Kfaraqab over who was the better shot.

But this time, with older eyes, I noticed other things. There was a pair of scuffed brown knee-high leather boots next to an old travel trunk. Inside was a pile of moth-eaten clothing: ribbed twill jodhpurs, a blue shirt and a khaki jacket with flapping epaulettes, long unmoored from their buttons. A few feet away, perched on an iron peg jammed into the stone wall and coated with cobwebs, was a faded pith helmet. Across the right shoulder of the shirt was the unmistakable garnet splash of dried blood. There was a similar, but bigger, stain across the back of the jacket.

“Those are uncle Assaf’s clothes.” Walid, my cousin, had appeared in the doorway. “The ones he was wearing when they brought his body back. ‘Teta’ [‘Grandma’] Helene kept them. What do you want with them? They’re nothing.”

Much was expected of Assaf, Esper and Elin’s eldest son. He joined the army after winning a place at the prestigious military academy in Homs, Syria. A career officer, he was a member of Les Troupes Speciales du Levant, part of the Vichy French Army of the Levant during World War II. After the Allies defeated the Vichy French in Syria and Lebanon in 1941, he became part of the new Lebanese army. He was apparently charismatic, unstinting and deeply principled. Being tall and fair with matinee idol looks only added to his magnetism.

But a promising military career was effectively curtailed by his politics. Assaf was a passionate member of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), or al-Hizb al-Suri al-Qawmi al-Ijtimai, a party that espoused the once-intriguing but ultimately hopeless ideology of its founder, the Lebanese-Brazilian emigre Antoun Saadeh, who dreamed of establishing Greater Syria, a territory that included most of the Levant nations as well as, peculiarly, Cyprus.

The SSNP’s manifesto was something of a curate’s egg. The secular ideal was arguably ahead of its time, but its quasi-Nazi paraphernalia, cult of the leader and advocacy of totalitarianism were ultimately too eccentric for a party with no solid confessional base.

And yet it was clearly fascinating enough for Assaf, who joined in secret in the mid-1930s and recruited his sister, Souria, who then met, fell in love with and eventually married Ajaj al-Mohtar, another party member and something of a warrior poet. Soon, all the siblings, as well as Esper, who was apparently always open to new ideas, were convinced by Saadeh’s worldview.

Everything went wrong in 1949, when Saadeh, with the help of Assaf — who led the party’s military wing and was by then married with three children and a fourth on the way — mounted a coup attempt against the government of Prime Minister Riad al-Solh. It failed spectacularly. Saadeh was double-crossed by the Syrians, who handed him over to the Lebanese authorities, who in turn executed him after a hasty trial. By now isolated, Assaf was killed in a gun battle with the Lebanese army just outside the Bekaa Valley town of Mashghara.

No one is sure exactly how he died. Souria, who by then was a fully committed partisan, believed he drew his service revolver and shot himself rather than be taken alive and executed “mittl il zaim” (“like the leader”), but no one really knows. What we do know is that the authorities denied his parents the right to properly honor him in death — to lay him out in their home — and so his coffin was placed under the shade of a mulberry tree in the garden until the funeral. Meanwhile, the men in the family made themselves scarce. My father, then aged just 24, fled to Damascus until he received reassurances that it was safe to return home. He was never “political,” and while his siblings’ fervor for Saadeh’s ideology never really dimmed, he gradually dissociated himself from the SSNP.

Meanwhile, Souria’s husband, Ajaj, was given the death penalty for his part in the coup, but the sentence was commuted to life and then annulled under a general amnesty. Yet the party and its members were always under scrutiny, and Ajaj was in and out of jail, while Souria struggled to raise six children in Beirut.

Blond and disarmingly unconventional, she rode a bicycle in tennis shorts to visit her imprisoned husband and used the same method of transport to carry out “missions” for the party. A staunch anti-Zionist, she lived through the hellish Israeli invasion of Beirut in 1982 and was incandescent to discover that the neighborhood idiot on whom for years she had taken pity was in fact Abu Reesh, the famous undercover Israeli spy.

She and Ajaj moved to Canada, where he died in 1990. Souria returned to Beirut with his ashes and lived in her Hamra apartment, where she lovingly maintained his library. She spent her last years in Cairo, where she died in 2000. When she heard that southern Lebanon had been liberated from Israeli occupation and control after the decision by the Ehud Barak government to withdraw from the country in May 2000, she refused her medication, saying she could now die a happy woman.

My father Bechara, initially at least, led something of a charmed life. He was blessed with boyish European good looks and the gift of the gab. During World War II, he became a favorite of the Arab singer and erstwhile triple agent Asmahan, who had a penchant for pretty young men despite being married. She died in a suspicious car crash in Egypt in 1944, and my father became a junior manager at Air Liban, later Middle East Airlines (MEA), Lebanon’s national carrier, where he eventually came to the attention of, and formed a friendship with, the founder and future prime minister, Saeb Salam.

In 1952, after a two-day courtship, he married my mother, Gisele Massad, an 18-year-old Greek Catholic from Cairo whose family had emigrated there from Lebanon’s Zahle in the 19th century and who had also worked for MEA in Cairo, in the sales office at Shepheard’s Hotel — until it was burned down in the Black Saturday riots earlier that year. Together they moved to Beirut, where my elder sister, Randa, was born a year later. Then they were posted to Vienna, where my father was awarded the Order of Merit for organizing support for stranded Lebanese during what has become known as the 1958 Lebanon crisis, which led to a U.S. military intervention in Beirut in support of the pro-Western Lebanese government of President Camille Chamoun, after religious tensions threatened to destabilize the country.

After that, they moved to London, where I was born in 1965 and where they were seen as something of a golden couple among Lebanese and Arab expats.

It was, after all, Lebanon’s much-vaunted golden age. The Lebanese lira was quoted among the so-called “hard” currencies, Intra Bank was the biggest finance house in the region and MEA had become the undisputed Arab carrier.

Summers were spent in Beirut, mostly at the Phoenicia Hotel, where my mother would install herself by the swimming pool. My parents were a very sociable couple but the marriage, riddled with infidelity, was on the rocks. They divorced in 1973.

Back in the village, with Esper dead and Elin in London, the house, which needed annual maintenance, fell into disrepair. Before Esper died, the house had been under lien. My mother, who hated the place, paid the debt with her own money and the house was signed over to my father. In 1971, in a move that would today be considered cultural vandalism, he refurbished it into what was known rather pompously back then as a “villa.” All that remained was the stone “qabu.” I didn’t realize it at the time — I was only 6 — but this was, and still is, what Lebanese do when they go abroad and make a bit of money. They come back and build a big house.

While my sister, by now engaged, was enjoying the glamorous tail end of pre-civil-war Lebanon, I was deposited in Zabbougha and into the care of my aunt Selma. The village proved a Narnia-like wonderland for a little boy whisked over from England. It was still very primitive. Many of the homes had no bathrooms or toilets, and our house had one of two televisions in the village. Apart from the weekly episodes of Kojak and Tarzan, we got our kicks from banging percussion caps with stones, hurling firecrackers at unsuspecting nuns, making catapults, riding hoops and seeing who could throw rocks the farthest, an eccentric test of manliness in mountain life (that involved an unorthodox but effective underarm technique). The highlight of the week was arguably the arrival, every Thursday, of the neighborhood ice cream van driven by Mr. Toufic. Twenty-five piasters bought you one scoop but, being the indulged son of a well-to-do “khawaja” (“gentleman”), I was allowed two, bought with the 50-piaster coin pressed discreetly into my hand by Selma after breakfast.

In 1974, my father indulged me further by getting me a donkey for the summer. It belonged to an old man, a distant cousin of my father, ramrod straight, turbaned and wearing the traditional “sherwal” (black baggy pantaloons), to whom I had to return it at the end of each day.

Weeks later, when I went, as usual, to pick up the donkey, which I had named Sporty after the popular Sport Cola, I saw a group of people gathered outside the man’s modest, two-room, single-storey house. I pushed through into the main room and walked over to his bed. He was dead and laid out, his arms crossed under his white face.

Later that morning, I watched the young men of the village make space for him in the “abr,” or tomb, and looked on in open-mouthed amazement as they casually stacked the skulls of the earlier incumbents — including, presumably, Esper and Assaf — on a rocky shelf at the back of the vault. One of them saw the look on my face. “You’ll end up here one day,” he said, pointing inside.

The civil war meant no more family vacations in Lebanon, although I went back once in 1981, when I was 16 and there was a lull in the fighting. Selma was by now on her own, protecting the house from looters and the local branch of the Kataeb (Phalangist) militia, who wanted to turn it into a district headquarters. Other than that, she worked on her pedal-powered sewing machine, quietly supported the “hizb” (the SSNP), smoked Rothmans and played patience.

In 1990, the year the war would eventually end, my father died in a helicopter crash in Sierra Leone, his last MEA assignment before retiring. His second wife decided that we should bring his body back to the village, which, after enjoying relative calm for most of the war, was being shelled on an almost daily basis, as Samir Geagea’s Lebanese Forces traded artillery blows with the Lebanese army, then under the command of the general (and later president) Michel Aoun, dug in in the hills above Zabbougha. It was a sideshow, part of the last and bloodier scraps in a conflict that had seen virtually all sides have a go at each other over the previous 15 years. But there were frequent lulls in the fighting, and it was decided that we could hold a service.

The “hearse,” a Mercedes station wagon with my father’s coffin sticking out of the back, was met at the corner of the entrance to the village and carried to the house. A choir from the church turned up, and hymns were sung over the casket, which sat in the same room where Helene had died exactly 13 years earlier.

That night, we held a wake in the main dining room. Electricity was haphazard. There were damp stains on the walls and paint was peeling from the ceiling. With my father in the next room, we gathered round the huge dining table he had shipped over from London years earlier.

It was a happy affair, despite the sudden and tragic circumstances that had brought us together. Souria was there with Ajaj’s ashes in her suitcase. Nohra had flown in from Abu Dhabi, while Selma and Irasema rattled around in black coats, both stricken with the dementia that had claimed their mother.

Selma, who, remarkably, was still living alone in the big house, had it particularly bad. She had no idea her youngest brother had died, nor why all these people had suddenly turned up. At dinner she sat in silence, until someone asked Nohra why she never married. Before he could answer, she lifted her head and said, “There was a man, but he is dead.” She then fell back into silence. She died a year later.

The next day, we slid my father’s coffin into the same tomb I had seen being “tidied” all those years ago. We were told that the ceasefire would hold until the following day, and so we told those who couldn’t make the funeral that they could pay their condolences at the house.

But the Lebanese Forces didn’t get the memo, and it was around lunchtime when I heard the first whistle of incoming howitzer rounds. One minute we were being served Turkish coffee and cigarettes from a silver salver by diligent, white-coated waiters; the next we were running for cover. “Cover,” it turned out, was under heavy wooden tables on the “leeward” side of the property, the logic being that, if a shell hit, it would hit the “windward” side first and have to travel through three walls before it reached us.

The artillery exchange lasted several hours. When the guns finally fell silent, one of my cousins popped in with two ancient bottles of Chateau Ksara Clos St Alphonse and a piece of shrapnel, presumably as a souvenir to take back to London. We Lebanese are, after all, very insistent when it comes to gifting.

In 1992, after 27 years of masquerading as an Englishman, I moved to Lebanon permanently. I got a job at the American University of Beirut teaching English and then eventually moved into journalism. In 1998, when our daughter was born, my wife and I decided to move up to Zabbougha and live in the house until the children started school.

In a blue metal suitcase that had belonged to Esper, I found a photograph taken in 1928 of Elin surrounded by her six children, presumably while her husband was toiling away in Mali. Behind her stands the Brazilian-born trio of Irasema, Assaf and Selma. Souria is to the right of her, while on the other side, holding his mother’s arm, is Nohra. Lastly, in front of her, leaning on Elin’s knee, is Bechara.

It is a remarkable photo in that it perfectly captures the characters of those in it. Irasema, the third daughter, kind and loving, who would marry a local schoolteacher; Assaf, dutiful and conscientious, with pen in breast pocket; Selma, the rock on which her siblings, as well as nephews and nieces, leaned, eyes blazing with steely determination. The impish Souria was already (in my mind’s eye at least) showing signs of rebellion. Nohra was the naughty boy, the chancer, in need of his mother’s love, while Bechara, the youngest, was secure in the knowledge that he was her little prince.

Elin looks sad, as she did in every photo. She never returned to Sweden, nor did she ever see her family again. Esper was often absent and, when he was around, he was cantankerous and, by most accounts, had a roving eye. It was probably not the happiest of lives.

A year later, the shopkeeper, who also doubled as the warden for the Maronite Church of St. George, told me that the family tomb, which was “full,” was to be “emptied” and given a lick of paint. All the bones, even those in coffins, would be taken out, put in a hole and covered with cement. I cheerfully pointed out that this could not possibly include my father’s coffin, which was hermetically sealed and, in any case, he was embalmed. Surely he would stay put.

Apparently not. It was out of his hands. He shrugged. As the mafia would say, “It is what it is.” I went home desperately upset at the thought of the imminent desecration. People I spoke to were annoyingly pragmatic. “The soul is the important thing. What do you care about bones?”

The sense of unease rumbled on for months until, one night, after a few whiskies, I went for a walk to the tomb. The hole had been dug up but not filled in. There was a temporary sheet of corrugated steel. I pulled it back to be greeted by a pile of bones and skulls set in an eerie rictus. Esper, Elin, Assaf, Bechara, Selma and Irasema. They were all there, somewhere, and I immediately felt a sense of peace. Suddenly, it didn’t really matter.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.