Listen to this story

Monique Chantal Duchene recalls her final moments in the Congolese village where she was born. A white woman takes her by the hand and leads her to an old sedan where two nuns in habits are reaching out to her with a toy gendarme and some lollipops. Her unruly, dark-blonde hair is gathered in two thick braids; she is wearing a Western-style cotton dress, not one of the batik pagnes worn by the women and girls of her village. The nuns tell her she is going on a great adventure. The 7-year-old cries out for Mommy, but the nuns tell her not to worry — they will be reunited once the civil conflict ends.

Monique never saw her mother nor her birth village again. Her country was going through a violent transition from the Belgian Congo to the newly independent nation of the Republic of the Congo, which would later be renamed Zaire and is now called the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Thousands of multiracial children like her were swept up in the frenzy, taken from their families and sent to orphanages and foster families in Belgium.

Today, as Monique approaches her 70s, she is searching for her mother, though she acknowledges that it’s unlikely she is still alive, given that life expectancy in the country is only 61 years and her mother would now be about 90. She desperately wants to know if her mother willingly handed her over to Belgian missionaries in the final throes of their rule. Perhaps she was worn down by three younger children, an abusive husband and villagers shaming her for having eight years earlier slept with a white man who died shortly after their daughter was born.

Or perhaps Monique, the illegitimate child of a Congolese mother and a French father in a village ruled by the Belgians since the turn of the 19th century, was abducted by the Catholic Church. Premarital sex remains a sin in the eyes of the religion that still dominates the country today, but back then it was also against the law for Congolese men and women to sleep with white people.

Her quest to find some answers led to me.

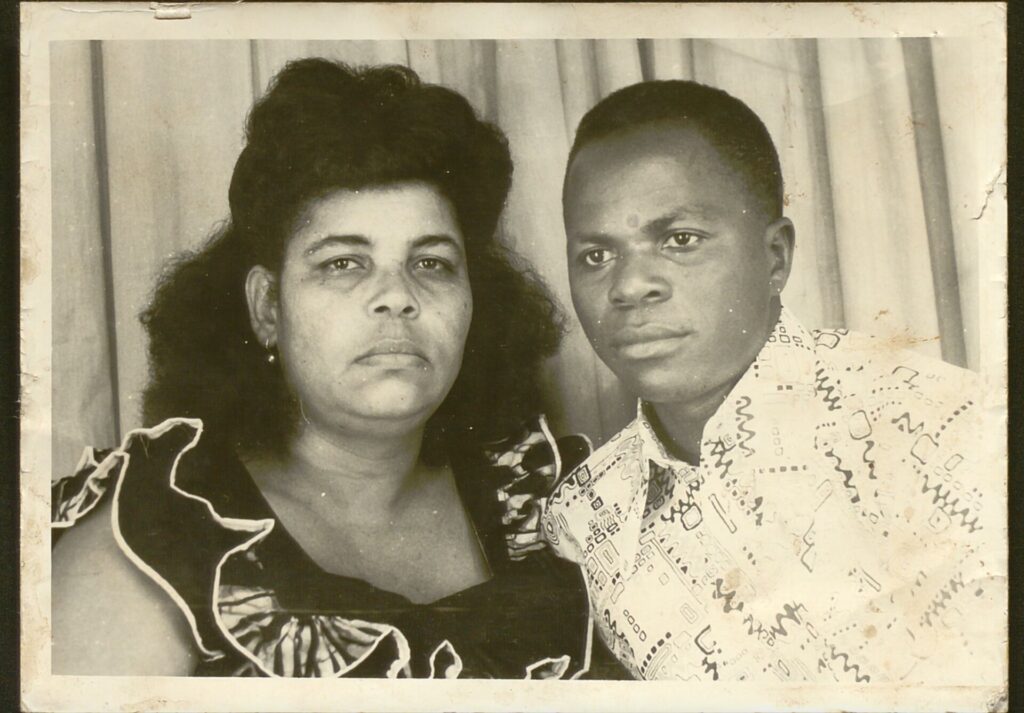

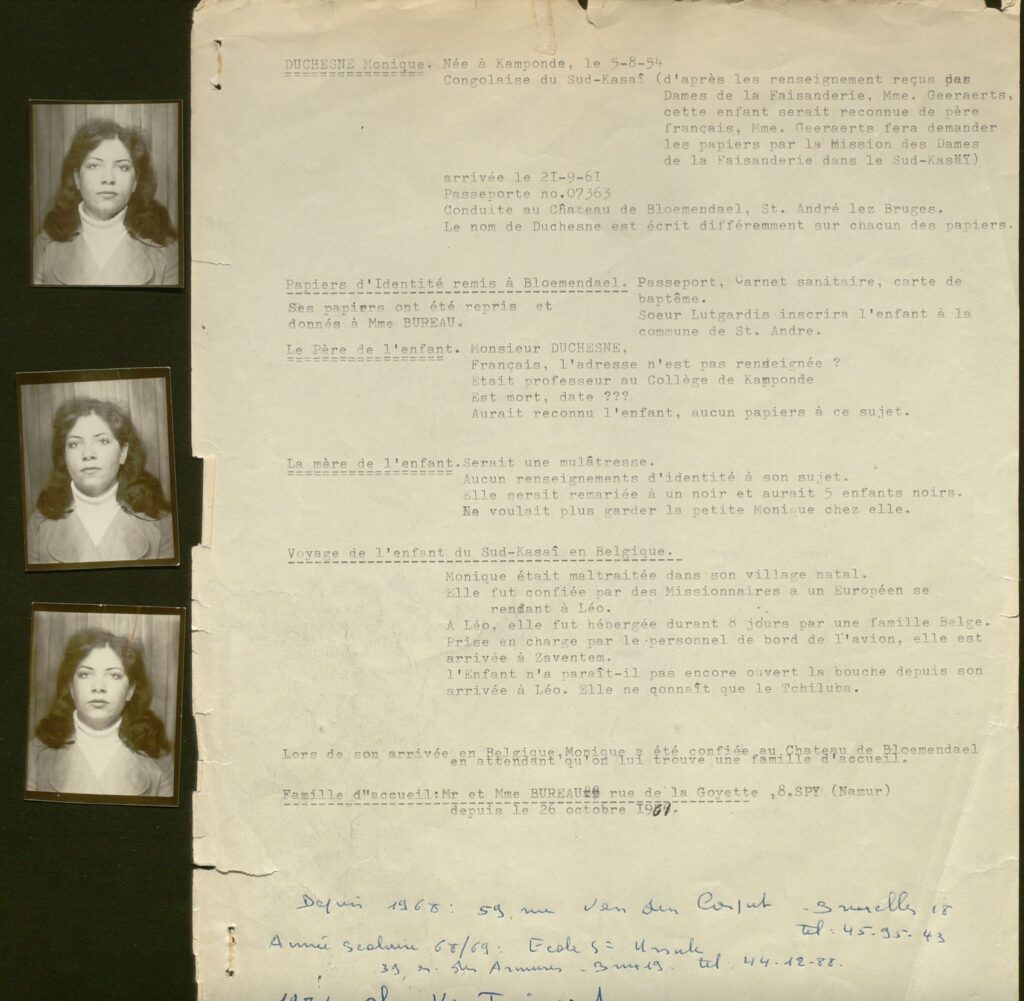

“We were viewed by the Belgians as an inferior race, a threat on their colonial grip, a loss of their undisputed power,” Monique told me as we sat together in her modest apartment in Eastbourne, a Merchant Ivory set of a seaside town on the southern coast of England. I had traveled from California to meet Monique for the first time since she found me in 2020, asking for my help. We scrolled through hundreds of pages of documents emailed to her from the National Archives of Belgium. Those included a handful of black-and-white photos from the late 1950s and early 1960s — the first and only ones she has of family. Among the depictions: her intense, tight-lipped mother and stepfather; one of her three half siblings; a blurry profile of her white father in a straw hat standing in front of a missionary building; and one of her taken by her first foster family in Belgium, a chubby-cheeked 8-year-old girl with a tentative smile.

I, on the other hand, have thousands of photos and hours of video of her birth village in the southwestern part of the country. I had stored them on an external drive to leave with Monique so she could study the images and sounds, perhaps find familiar faces among the elderly, recall some of the hymns sung in church and hear the crackling cooking fires and ululating mamas.

I had spent two years in Kamponde, Monique’s hometown in Kasai province. I was a Peace Corps volunteer from 1979 to 1981, nearly two decades after Monique’s abduction. I returned to this village three times over 40 years, the last time in 2019, to thank the people for taking such good care of me when I was so young and to learn how they had survived recent uprisings in the region. I am writing a book about this village and some of my friends there, about how we have all changed — and remained the same — over four decades.

I am also reexamining my role in extending the paternalism and neocolonialism that remains across much of Africa today; the “white savior” journey many of us took as the Peace Corps sent thousands of young Americans to a country ruled by a dictator our government had helped put into power. I don’t regret it. I loved teaching, made lifelong friends with some villagers, students and other volunteers, and found my purpose in life as a journalist who excels at telling stories about people in countries most Americans would never visit. But I am reckoning with the enormousness of my ignorance of Congo’s colonial past when I arrived there at age 21, a freckled redhead stepping down from a Land Rover, only vaguely aware the government I now worked for had been complicit in the country’s suffering in the second half of the 20th century.

There is an African proverb: Until the lion learns to speak, the story will glorify the hunter.

I hope that telling stories like Monique’s will help give voice to the lions.

On Nov. 19, 2020, about a year after my last trip to Kamponde, I received an email from Monique via the contact page of my website where I occasionally blog about Kamponde, my former students, the cook who watched over a generation of volunteers, the rival chiefs, ethnic conflicts, the clever Catholic nuns and the progress and hopes of the DRC’s more than 100 million people.

Monique had just received the documents from the Belgium archives, learning she was born in a village called Kamponde. She Googled it and my name popped up. I’m one of the few people who has publicly documented life in Kamponde, so it’s not hard to find me.

“Dear Beth, I’m sorry to contact you out of the blue like this, but I found your articles about Kamponde in DRC and have recently found out at the age of 66 that is where I was born,” Monique wrote in the first of dozens of emails we have since exchanged.

She went on to briefly tell me her story, then ended: “I now live in England and took up British citizenship a long time ago, but that doesn’t mean I have forgotten my roots. As you can imagine it has been a challenging situation all my life — not knowing which world I belong in — and there are many of us out there feeling the way I do.”

An estimated 20,000 of these multiracial children, mostly girls, were torn from their villages in the Congo and flown off to Belgium, never to see their families again. Some of those children also came from neighboring Burundi and Rwanda, which were also under Belgian rule until 1962.

They were told as children that their removal from their homes was to protect them from the political upheaval of independence, but most now believe it was to hide a nation’s shame at the European men who fathered these “metis” children during Belgian rule. Once in orphanages or taken to foster families, the children were not recognized as Belgian citizens; they were stateless and held no birth certificates.

Monique did not receive her first passport until after she immigrated to England to work as an au pair. She was never granted Belgian citizenship, despite having lived there for more than a decade. Her attempts to get a French passport were turned down on the basis that she had no paperwork proving that her biological father was French.

At 19 and still stateless, she had to get an attestation from the Zairian Embassy in Brussels before she could board a ferry to cross the English Channel.

Like most young women her age she loved fashion and the Beatles, and could not wait to start this new chapter as she inched into adulthood. Upon arrival in the country that would eventually grant her citizenship, she was detained for several hours at the ferry terminal in Dover, forced to strip down to her underwear and examined by a male doctor.

“Because I had a piece of paper from an African embassy, they said I might have been carrying a tropical disease, never mind that I had been living in Belgium for more than a decade,” Monique told me during the two days we spent together last year. “It was so humiliating, but I was alone and quite helpless.”

Like so much of her early life, “I just got through it.”

Belgium’s then-Prime Minister Charles Michel made the country’s first formal apology in 2019 to these African-born children, many of whom are now in their 70s and 80s.

“In the name of the federal government, I present our apologies to the metis stemming from the Belgian colonial era and to their families for the injustices and the suffering inflicted upon them,” he said before Parliament, placing a hand over his heart as he addressed a group of multiracial adults in the audience. “I also wish to express our compassion to the African mothers, from whom the children were taken.”

Not all the abducted children were sent to Belgium. Some were placed in Catholic boarding schools at missions across the Belgian Congo where, according to their testimonies, they were treated like prisoners, left malnourished and sometimes raped or physically abused.

“When this kind of love is taken away from children, they’re going to carry that scar for the rest of their life,” Monique Bintu Bingi, one of the five plaintiffs in a 2021 lawsuit against the Belgian government, said in an interview with Al Jazeera. The plaintiffs say their abductions were racially motivated and constitute crimes against humanity. The five grew up together in one of these Catholic missions in the same Kasai province where Monique was born and where I served in the Peace Corps. They were told they were “children of sin” and that the devil had created them. When violence erupted during the move to independence — both against foreigners and among rival ethnic groups — the Belgian missionaries abandoned the children, leaving Bintu Bingi and the older children to take care of the younger ones. Some of the babies died of malnutrition; the women still have nightmares about their rapes by local militiamen fighting for control of the province.

The plaintiffs are seeking $55,000 each in reparations but lost their case for compensation in December 2021. According to the Brussels court ruling seen by The Associated Press, while their treatment as children was unacceptable, it was not “part of a generalized or systematic policy, deliberately destructive, which characterizes a crime against humanity.” Lawyers for the women say they will appeal.

Belgian King Philippe visited the DRC in June 2022 for the first time and expressed regret for the misdeeds of his ancestors.

“This regime was one of unequal relations … marked by paternalism, discrimination and racism,” he said. “I wish to reaffirm my deepest regrets for these wounds of the past.”

For Monique and so many others like her, the wounds are very much present.

The government officials and nongovernmental organizations helping these women uncover their pasts are the same now helping Monique with the search for her own family members. She was invited by the Belgian government to Brussels in October 2022 to give testimony. The government didn’t help with expenses, and Monique is on a tight fixed income — but she bought a round-trip ticket on the Eurostar from London to Brussels and two nights in a hotel because she hoped those officials would help her find her mother and siblings.

Some 40 to 50 multiracial elders attended the two-day meeting; Monique said she appeared to be the only one who traveled from outside Belgium. A group of young white Belgian researchers were tasked with interviewing the former Congolese, and Monique spent hours one day telling them her story. She was disappointed, however, when she asked them to explain their ultimate goal. They told her that the narratives would go into government archives and that, no, they were not tasked with helping find families back in the DRC. Some of the other attendees believe the testimonies will go toward rewriting the country’s history and textbooks to include this period of abductions. That’s a good thing — but it doesn’t bring Monique any closure, nor does it reopen relationships with her family from Kamponde.

“I told them that I never saw my mother again, that I never saw my family again,” Monique told me. “And I asked if the Belgian government was setting something in motion to help people like me find their families — and basically the answer was no. They were very empathetic and obviously very sincere, but they were not going to help me.”

Once again, she left Brussels with a sense of abandonment and loss — and says she didn’t breathe deeply until she was back on English soil.

Monique was born in Kamponde in 1954, several years before I was born in Portland, Oregon. She grew up an impoverished outcast — yet always looking for a better sense of where she belonged. I grew up in relative privilege among the redwoods and suburbs of Northern California, having had a progressive childhood that would lead me to join the Peace Corps to teach in the same school as Monique’s father, Andre Duchene.

The Peace Corps has three goals. The first is to help the people of interested countries in meeting their need for trained adults; the second is to promote a better understanding of Americans in those countries where they serve. I was thrilled to wake up one morning to this unexpected email from Monique, as the third goal of the Peace Corps is to promote a better understanding of other cultures among Americans. I could share her story with others, include her in my chapter about the Belgian Congo, possibly lead her to the whereabouts of family members.

I also wondered if the same cosmic twist that brought me my daughter led me to Monique. I first returned to Kamponde on a reporting trip for the AP, to write about the looming civil war from the perspective of those in the village, 15 years after I left it as a volunteer. Some of the villagers were upset that I didn’t yet have children. In Congo, children are a symbol of wealth and happiness, social stability and status, offerings to ancestors counting on them to maintain the family bloodline. I explained that my then-husband and I had been trying for years but appeared unable to conceive, likely because of a medical condition from my youth.

On the last night of that visit, a bunch of us were sitting around a bonfire, and I heard women chanting my name in their songs as they danced to the rhythms of bamboo xylophones. I asked what they were saying in the local dialect, Tshiluba, which I had mostly forgotten. The former Peace Corps cook, Tshinyama, told me they were praying to their gods to bring us a child.

Several months later, I was throwing up in the bushes of the Kinshasa residency of President Mobutu Sese Seko, the revered and reviled man who had led the country for 32 years, amassing billions while his people remained among the poorest in the world. Mobutu, in his trademark leopard-skin toque, was holding what would be his last press conference before he was forced to step down as rebels approached the capital. I was a West Africa correspondent for the AP — realizing I might be pregnant as I tried to shout questions at the falling dictator.

As Monique and I communicated, I learned I had often walked past the cement bones of the Texaco gas station her father had established, past the graveyard where he likely rests today. An uncle who may have been instrumental in sending her away was the same Catholic deacon who often gave the Sunday masses I attended to enjoy the hymns and community. My best student was the son of a prominent businessperson who had taken over the Hotel Evelina, after the sudden death of its owner, Monique’s father.

It seemed like the universe was willing us toward each other.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that we were destined to meet,” Monique told me. “I read your blog and was driven by a force that compelled me to reach out to you. I knew it was a long shot, but I waited patiently to see what the universe would bring back to me. And it led me to you.”

Monique’s father died at age 56, shortly after she was born. Records show that he died of cancer and was a teacher at the Institute Untu, the same secondary school where I taught English, history and some Bantu philosophy, once the headmaster learned that I had graduated with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy several months before I landed on the doorstep of his crumbling classrooms.

Monique’s mother, Jeanne-Rose Louise, was a teenage housekeeper in the home of Monique’s French father, and was herself also a metis born of a Congolese mother and Scandinavian father. Kamponde was once a thriving commercial enclave with running water and electricity, dozens of European missionaries and fortune seekers, and a renowned secondary school attended by the children of missionaries, wealthy merchants and the elite political class. Etienne Tshisekedi, the great opposition leader, onetime prime minister and father of the current president, Felix Tshisekedi, attended the school.

Though Monique’s father is listed in the Belgian government archives as a teacher at the school, it seems that he was more of an entrepreneur. He ran a grocery store and built a gas station and a hotel. Duchene also leased from the Belgians dozens of acres of palm trees, whose nuts produce cooking oil and whose fermented sap I once choked down in acknowledgement of the hard work of those who carried heavy calabashes filled with the murky alcohol on poles balanced across their shoulders.

The foreigners had free rein to run the local businesses, schools and churches as well as exploit the natural resources of the land — all in the name of their god. As the late South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu once said: “When the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible, and we had the land. They said, ‘Let us pray.’ We closed our eyes. When we opened them, we had the Bible, and they had the land.”

Neither Monique nor her mother ever benefited from any of her father’s wealth. The archives from the Foreign Office in Brussels indicate her father left a large inheritance estimated to be in the millions by today’s standards. The Belgians contacted the French Embassy and found her father’s only brother to tell him of the inheritance; he died in 1974, and Monique never learned if he received the money.

“My mother and I are not mentioned in the archives about my father’s family inheritance. But then again, we had no rights,” she said.

Monique’s only photo of herself as a child shows a round-faced, fair-skinned girl with short curly bangs and two thick braids, dressed in a Western-style plaid dress. The photo of the 8-year-old girl was taken in 1962, months after she was taken from Kamponde and put in an orphanage for multiracial children outside of Brussels. She had been flown in from Kinshasa, the capital still called Leopoldville after Belgian King Leopold II, who terrorized the Congolese as the sovereign slave master of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908.

In his 1899 novella “Heart of Darkness,” Joseph Conrad describes the treatment of the Congolese by the Belgian king as “the vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience.”

Adam Hochschild wrote what most consider the definitive contemporary book about the monarch’s reign, “King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa.” When I read the international bestseller nearly two decades after I left the Peace Corps, I was aghast at how little I had known about the genocide of the ancestors of those with whom I had lived for two years. When we discuss the atrocities of African dictators and warlords, such as Charles Taylor of Liberia, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe or Uganda’s Idi Amin, we should consider that this Belgian monarch — an absolute ruler who never once stepped foot in the Congo Free State — was responsible for half of the country’s population being murdered or worked to death. Hochschild estimates that population loss during Leopold’s 23-year rule may have been as high as 10 million people when including those who were never born because of the disruptions of the forced labor system. Tens of thousands more had their limbs hacked off by machete when they did not meet their quotas in his rubber plantations.

Leopold, Hochschild writes in the introduction of his bestseller, was a man “as filled with greed and cunning, duplicity and charm, as any of the more complex villains of Shakespeare.”

I didn’t teach Shakespeare, but I did put on a school play, “The Crocodile King,” written by another Peace Corps volunteer and performed by students in my English club. The school had been staffed for decades by the generation of Belgian missionaries who came after the king’s personal rule. They ran the schools and built health clinics and hospitals under the Belgian administration, demanding loyalty to the Catholic Church. Few remained in the country by the time I was a volunteer, though we still had Pere Paul, who had taught history for decades. He was retired from teaching but still gave Mass on Sundays and was the only one who could flip the switch on the lone electricity line in the village, which he did for my school play.

I never had the courage during our Sunday brunches at the mission to ask the grim old man with the long white beard whether his lessons included the history of Leopold’s rule. I was too eager, I’m ashamed to say, for the freshly baked bread, real butter and fried eggs. I did teach my students, however, that an African-American Civil War soldier, George Washington Williams — later a Baptist minister, lawyer and journalist — was one of the first to travel to the Congo Free State and alert the world to the king’s atrocities. The Belgian government finally pushed their sovereign aside to take control of the country, ruling from 1908 until independence in 1960.

Monique’s recollections of the violence in the wake of that independence are among the last memories of her brief childhood in Kamponde.

“I become aware that my environment is degenerating into a dangerous and chaotic one, tribal wars are rocking our lives, a civil war is emerging, men turn up regularly, brandishing sharpened machetes,” Monique recalls in the first draft of the memoir she is writing. “They are ruthless, totally unmoved by cries and begging. Family and friends are dragged away, never to be seen again. The Europeans’ villas are burned down, ransacked; looting is rife.”

An estimated 100,000 people were killed in the four years of violence that followed independence, including the nation’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba.

“Humanitarian organizations rush in to intervene,” recalls Monique. “Armed men with rifles, groups of white foreign mercenaries are marching in camouflage through our village. They keep glaring at me, inquiring as to why I’m here, seeking to draw me into conversation.”

It was then, Monique believes, that her mother became fearful for her fair-skinned daughter and may have agreed to hand her over to the Belgian missionaries for her own protection.

“Over the years her decision has stirred strong emotions; I’ve been submerged in anger, sadness, a sense of abandonment and reeling from a relationship never truly fulfilled,” Monique writes. “But as I matured, I have tried to understand her actions and find it in my heart to forgive her.”

Monique told me how she was sexually molested by a Congolese priest at the Catholic mission in Kamponde and again, while still a little girl, by a Congolese teenager in that first orphanage outside Brussels. She would then be placed in several foster homes until she was once again orphaned at 16 and set out on her own.

“A traumatic childhood leaves you vulnerable, with so many scars, and the subsequent choices you make are not always in your best interest,” Monique told me. She made bad choices in men, she said, but has been blessed with three children and five grandsons.

“I bear no grudges. It’s just the way life is. I call it being human.”

The Belgians were nothing if not fanatical about the records of these abducted children. When Monique read about the multiracial women in Brussels seeking reparations, she got in touch with one of them who gave her the contact details for the government agency working on the archives. The 253-page PDF file sent to Monique in 2019 by the Belgian government at her request had been assembled over the years by the Association for the Protection/Promotion of Mulattos. It includes such details as photocopies of her Sabena Airlines boarding pass for her flight from Leopoldville to Brussels. Her confirmation card with a white Jesus and a little white girl in white dress and veil, dated May 8, 1966, includes the menu of mushroom shells, parsley potatoes and Communion cake.

“It was a big shock, as I had sought information over the years but never got anywhere,” Monique said. She learned that her father had a brother in France who died in 1974 but had lived long enough that she might have been able to know him and other French family members. “I am deeply upset that the Belgian Foreign Office had so much information on my father, which could have been shared a long time ago.”

The first page of the document was like a punch to the gut, humiliating and hurtful. It was not only racist in tone but definitive about her mother’s alleged neglect. Her mother, the document reads, was herself a “mulatresse” who married “a black” and would have five “black” children.

“She no longer wanted to keep little Monique at home,” the dossier reads in French. “Monique was mistreated in her native village. … She has not opened her mouth since arriving … as she only knows how to speak Tshiluba.”

The very next page is a letter from her mother that she never received and read for the first time only when the dossier arrived two years ago. Written on Feb. 10, 1981, when Monique would have been 27 and already living in England, the letter is a plea for her to write back. “My dear, my sweet girl, your mother is still alive and not at all at peace with the fact that I don’t hear from you. Are you, my beloved, reading this? Do you still think about me or love me? I kiss you from afar … your loving mother, Ntumba ex-Jeanne Rose.” That is followed by a letter back to her mother from the director of the association telling her that he cannot deliver the letter because her daughter had left Belgium in 1973. Several other letters from her mother never explain if she handed over Monique or whether her daughter was taken from her.

There follows page after page of handwritten letters that were never delivered, including one from a younger brother, Jean Bosco Kasombo, asking for her whereabouts and saying her family cries for her. A cousin who lives in Belgium was looking for her. And then there are dozens of documents about her various foster families and details about her education and behavior.

A caseworker for the international family-tracing service of the Red Cross in London, working with their offices in Kinshasa, was searching for some of Monique’s remaining relatives but recently wrote to her to let her know they had found none and would be halting their search.

“To say that I’m devastated is an understatement,” Monique told me. “At this stage in my life, time is no longer on my side, and there is an urgency to everything.”

I have been working my contacts via my Peace Corps and Congolese friends, but we have not been able to locate any relatives. The closest we have come to touching her family came through Congolese friends in WhatsApp exchanges. One of them pinged a friend in the DRC’s southernmost city of Lubumbashi to ask if his elderly father remembered Monique or her parents. Eighty-nine-year-old Papa Honore Lumuangla did indeed. The native of Kamponde worked with Monique’s father and painstakingly wrote his memories in tiny script in Tshiluba.

Papa Honore — I use the honorific for elderly people in Congo — said Monique’s father was nicknamed “Mafuta Duchene,” a Tshiluba word akin to “fatty.” The lone photo of her father does show that he was a stocky man. He writes that Duchene was employed by the state to provide wood to run the steam locomotives of the BCK railway company that ran past Kamponde and whose later models I often took to get up to the nearest city for supplies. Papa Honore writes that Duchene recruited men from around the region; some trained as blacksmiths to make the axes needed to fell the eucalyptus trees.

Once the government contract ended, Duchene built his Texaco station and hotel.

“Mr. Duchene’s hotel was overwhelmed during major holidays such as Christmas and New Year’s Eve, with white people coming to spend the holidays in the village instead of going to Europe,” Papa Honore writes, adding that Duchene “was tall and in perfect health. He died of a heart attack, not from cancer,” as Monique’s government document claims.

A Requiem Mass was held in Latin in his honor in the same mission church I often attended on Sundays. “The chapel was crowded with people, especially whites from all over: nuns, missionaries from the Brothers of Charity congregation. He was buried in the Kamponde Mission cemetery near the Kavunda River. After his death, as there was no will, the state recovered and sold Mr. Duchene’s property.”

Much of what Papa Honore writes syncs with the government dossier. But it’s the more personal notes from the elderly man that touched Monique most.

“To Monique’s question of whether she had been rejected by her mother,” he writes, “I will tell her this: The Belgians in the Congo were very strict in their way of living with the Blacks. They had instituted a kind of general census aimed at identifying and recovering all the children resulting from the union between a white man and a Congolese woman and they were dispatched to the countries of origin of their male parents. This is just how the Belgians acted.”

He writes that the Rev. Mundondo Nicodeme — the priest who helped celebrate Mass with Pere Paul when I was in Kamponde — was Monique’s uncle. “Mundondo Nicodeme knew very well that Monique’s mother was from his family,” he writes. “He was a highly educated man who had spent a lot of time in Europe, particularly in Belgium and France. It was because of him that the Peace Corps members arrived in Kamponde, coming from the United States to teach at Institute Untu. He was the only person in all his family who knew Monique’s story. All those who remain today do not know the story and are surprised to learn that they have a relative who was torn from the family by the wickedness of the Belgian colonialists.”

Papa Honore refers to Monique as a daughter of the village, a relative to all.

“Talk to my child Monique wherever she is … and tell her that her mother did not abandon her,” he writes. “If ever her friends or her children ask her where she comes from, let her know that she comes from central Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the province of Kasai. May the peace of the Lord Jesus be with her!”

My newfound friendship with Monique has caused me once again to thank the Peace Corps for having led me to so many fascinating people, both in Kamponde and across the globe. We all affected one another’s lives in small ways. As a secondary school English teacher, I truly believed I was preparing my students to succeed in life and help their country progress. I left the village of Kamponde proud of my accomplishments, watching many of my students pass their college entrance exams and begin their own careers, such as they were in a country riddled with corruption and inequity.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed an executive order, keeping his campaign pledge to establish a national Peace Corps with the mission of promoting world peace and friendship. I know we didn’t change the world; nor did we move the needle on world peace. But the friendships and hardships led many of us to commit to careers that just might improve the lives of a few others.

“It was the most transformative two years of my life — and I think about Zaire every day,” said Mike Tidwell, a volunteer who served a few years after me in the same region teaching farmers how to build fish farms. Not long after coming home he wrote the gut-wrenching Peace Corps memoir, “The Ponds of Kalambayi.”

“I went to 200 funerals in two years, most of which were for children under 5,” Tidwell told me over coffee outside Washington, D.C., where he is a well-known environmental activist. “You go into the Peace Corps thinking we’re going to learn what it’s like to be poor, and part of what happens is you learn what it’s like to be rich, ridiculously rich.”

Like me, Mike said a day doesn’t go by that he doesn’t thank his lucky stars. His witnessing of hunger and malnutrition and the government corruption and cruelty compelled him to come home and tell the world. And then to fight. “My time there motivated me to do something about justice. I’m a climate activist today in large part because of my experiences in Zaire.”

Many former volunteers concede they did little good, but most of us know that we built friendships that opened some doors and changed a few lives.

“Oh, the intensity of the friendships,” Tidwell said. “Everything was stripped away. It was human to human. I mean, I had friends the likes of which I’ve never had since.”

Yet many former volunteers like me believe the Peace Corps could and should be so much more, with better training and more recruitment of people of color. The organization could partially adopt former Peace Corps Volunteer Liz Fanning’s CorpsAfrica model, which places African volunteers in their own countries, or it could bring host country nationals to the United States for training and experiences to take back home. I can’t tell you how many Congolese I’ve met over the years who would be fantastic teachers or help address the dire shortage of trained medical personnel. And I know many who came to the U.S. to study and returned home to apply their new skills.

One encounter with a young stranger on a freight train back in 1996 changed the way I think of my service. I was in an open boxcar of a freight train, having just completed my first trip back to Kamponde as a journalist on my first overseas assignment. The Peace Corps had pulled out five years earlier because of violent unrest, and the younger generation had only heard of the American volunteers.

“What brings you way out here, madam?” a young woman named Benesha asked me as she sat down next to me, our legs dangling over the side of the boxcar. I told her my story in French as we watched the sun rise over the thatched huts along the railroad line. She nodded and sucked in her breath in that endearing Congolese way that means keep going, I’m listening.

“I heard about you Peace Corps volunteers,” Benesha said. “My uncle in Tshimbulu worked with a volunteer named Brian, who helped him build a fish farm. He’s always telling stories about the crazy American who worked day and night, how he loved his palm wine, the girls, the dancing.”

I chuckled and told her I had partied with Brian several times and then asked whether the fish farm was still up and running. It was indeed. Her uncle had taught others to farm the tilapia and was now putting her through college to study French so she could become a language teacher.

“So, did you find what you were looking for?” she asked. “Do you think you did any good here?”

I shrugged and ran my fingers through my short red hair. “A little, I guess.”

She nodded and smiled. “Well, isn’t a little good better than none at all?”

This article was published in the Fall 2023 issue of New Lines’ print edition.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.