During a recent trip back to Syria, I found myself in the precarious position of having to replace my national ID card, which had gone missing.

Such a thing would have been a disaster in wartime, when Syrians relied on the black market for lost and stolen ID cards as a way to fraudulently bypass mandatory military conscription and arrest warrants by a regime hell-bent on punishing them for showing dissent. Back then, applying for a replacement would have flagged a citizen as a potential smuggler; a wrongdoer of any number of crimes, including “aiding and abetting terrorists,” which was how the Bashar al-Assad regime had summarily labeled at least half the country, including most of its rural folk, since the first days of the uprising when things were still peaceful.

But now that the regime has won, its main focus has changed. All it cares about is money. And with a collapsed local currency that has forced even the coffee vendor to use a money-counting machine because customers pay with bags full of cash, everyone keeps track by converting in their head the U.S. dollar value of their earnings. That is how officials and petty bureaucrats think about the bribes they have come to expect at every twist and turn during their interactions with citizens. My lost ID card presented an excellent opportunity for such a thing, though at first I could not have known to what extent.

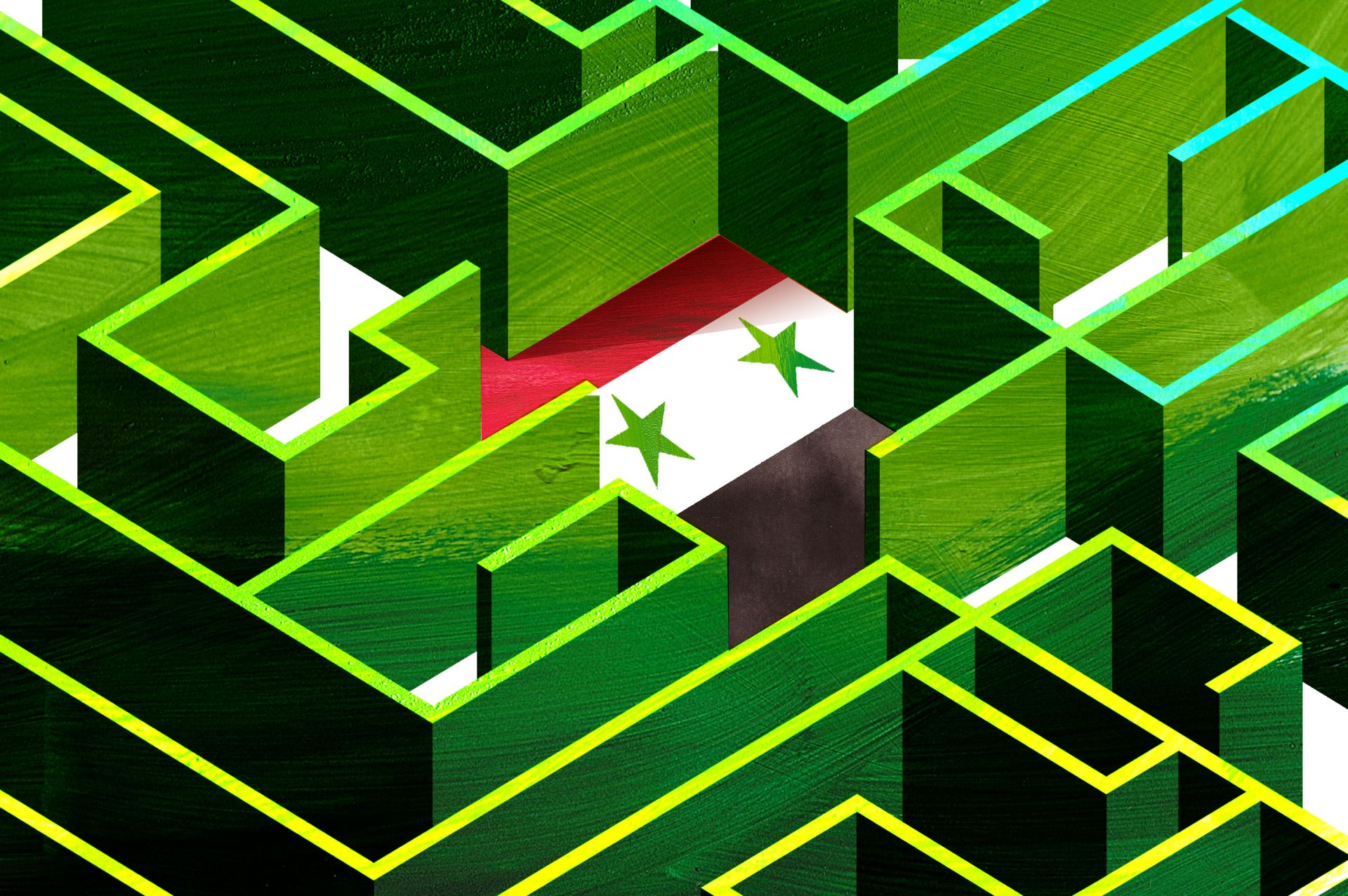

Thus commenced my journey into the belly of Assad’s bureaucracy, which, as I would learn, had become hungrier and more emboldened than I remembered. To help me navigate this labyrinth, including the delicate protocols of handing out bribes (which is partly science but mostly an art), a cousin of mine graciously accompanied me, his leather jacket filled with wads of cash tucked and hidden inside secret pockets.

At the Interior Ministry, we found ourselves inside its edifice, having to climb stairs and walk through corridors, popping in and out of offices and shuffling from place to place. Accustomed to greasing hands and navigating red tape, my cousin, a young merchant, asked for this person and that and filled out forms on my behalf, coaching me what to say at every junction.

“You lost your ID card here, in this neighborhood, just down the street, by the fountain, OK?” he instructed me in a discreet whisper.

“OK,” I said, figuring it was as good a place as any to lose an ID card. With that, we were ready to file the police report.

But before we could go to the police precinct to fill out the paperwork, we first had to tell our story to the local mukhtar — akin to a district mayor — who sits inside a stand-alone office, a one-room structure made of concrete, with windows and a door that opens onto the sidewalk. Every neighborhood in the city has such a structure, and it is where locals go to interact with representatives of the state and initiate the bureaucratic paper trail that marks life’s main events, things like marriage, birth and death certificates or, in my case, an application to replace a lost ID card.

We had started our day at 8 in the morning, and it was midday when we arrived at the mukhtar’s office, only to find it closed. Perhaps he had stepped out for lunch or to run an errand, we thought, so we stood around and waited for his return. A ragged-looking family of five showed up and, like us, were disappointed to find the office closed.

“He was just here!” the dad, dressed in pantaloons, said partly to us and partly to his own family. “He just sent us for a signature around the corner. Where did he go?” His voice carried the desperation of someone who had awakened his family in the middle of the night and corralled them to make the hourslong trip by public transportation from their village — located somewhere in the rural provinces where, since the war, basic government services are no longer offered — to the city to cut through the red tape to register their kids for school or transfer a property deed. This would explain the listless looks of his children and the dark circles under their eyes.

Luckily for all of us, the mukhtar showed up not too long after. He must have indeed gone to grab lunch or run an errand. Unlocking his office, he invited us all in. After taking the documents from the rural family, he gestured to me, inquiring what business might have brought me to him.

“I need to report my lost ID card,” I said. My cousin promptly stepped forward and handed him my documents.

The mukhtar glanced at my paperwork with a grimace. He hemmed and hawed a little, then redirected his focus to the family and shuffled paper on his desk as if to buy some time to think of a response. It took a minute or two before he glanced up at me and announced that he couldn’t help. “You must go to the other mukhtar, over there,” he said, pointing at the other side of the public square. He gave no reason for this, and we did not inquire about one before we dispatched ourselves.

Later, we speculated that he was probably too scared to touch my documents. Applications for lost or stolen national ID cards remain something of a lightning rod for government officials, and no one wants to be associated with helping a citizen navigate such a quagmire. Besides, these applications can be scrutinized up the chain, where a superior might rightfully suspect that subordinates must have received substantial bribes to facilitate such a thing and would therefore squeeze them for a share of what they imagined to be a sizable amount of cash — enough perhaps to fill a suitcase with Syrian pounds.

We found the second mukhtar seated behind his desk inside his office by the sidewalk, looking bright-eyed and attentive. Here, we had a different reception.

“I need to file a police report for a lost ID,” I told him. He sized us up, then proceeded with a slew of questions: Where was it lost? When was the last time I had it on me? Where do I live now? Which neighborhood, exactly? I did not mind his line of questioning because at least it meant he was prepared to help us move the process along.

From our exchange, it quickly became clear to him that I was an expatriate, because my “tongue spoke with that telltale heaviness” of Syrians who live elsewhere. He ascertained also from my local address that my home was in a well-to-do Damascus neighborhood, “not too far from me, actually,” he added, looking impressed. This was code not just for class but for the urban-rural divide that continues to fester in Syrian society. We were both urbanites, true Damascenes, presumably from good families, whereas the first mukhtar we visited was a man of humble origins, one of many rural officials relocated by the state to serve in an urban area, which is a thing of great consternation to urban elites, who cannot help looking down on rural folk.

Entwined around this divide is also the sectarian reality that, as Syria’s civil war raged, it was only the rural Sunni Muslims who found themselves fighting the regime. This has earned them contempt from government officials, especially those who belong to the same (provincial) Alawite sect as the Assad clan, as well as from Sunni Muslim urbanites who think they’re better than everyone else.

These complexities seemed to be in play at the office of the mukhtar when he decided that we were of the same ilk, and so he moved on to his next line of inquiry.

“This is you and this is you?” he asked, sounding incredulous, pointing to both of my headshots — one from the day before and one from 25 years earlier, from a photocopy of my lost ID, which thankfully I had in my possession to help facilitate the process. Granted, I was older now and my hair was long and silver, but there was more to his query than the obvious passage of time. He was subjecting me to a classic interrogation technique that Syrians had become all too familiar with during the war. An official asks for your documents. When you produce them, the official, almost automatically and without scrutinizing them in any convincing way, tells you that they are fake, accusing you of forgery and fraud. During the war, this was a way for regime henchmen to shake you down, knock you off kilter and see if you were scared easily. If you were, then what were you hiding? It must have been part of their training, an old Russian trick repeated in their pseudoscientific “psychological warfare” handbook.

I responded to the mukhtar the same way I used to respond to armed guards during the war: I stayed calm and insisted in a monotone voice that my documents were not fake. Both photos were indeed of me.

During this exchange, we were interrupted by a man in his 30s who popped his head bashfully into the mukhtar’s office but said nothing, which seemed to annoy the mukhtar, who decided to deliver a reprimand.

“Eh! You poke your head in looking for the mukhtar and you don’t ask where’s the mukhtar? Do I not look like a mukhtar to you?” he asked.

“Oh, no, you do,” the man replied, meek and embarrassed.

“Go on, what do you need?” the mukhtar asked. His voice carried well in a boisterous baritone.

“I need a change of address for a marriage certificate,” the man said.

“Who gets married in today’s circumstances? Why would anyone get married nowadays?” the mukhtar quipped.

“The paperwork is not for me, actually. But they need it for the bride-to-be,” said the man, growing smaller.

“How can I convey to you the message of ‘Who gets married these days?’” the mukhtar said. “Do I send it by camel? By sheep? By goat?”

His tone was mocking, but in asking about marriage he was not wrong. Who would want to start a family and bring children into this world? I hadn’t been to Syria in years, and what I now saw left me wondering how people were getting by and managing their affairs, given the inflation and corruption and lack of opportunity to make an honest — or even a decent — living. This was a country in postwar freefall, where the victor had no virtue and the victim was all but forgotten; a country still fractured, a people condemned to live at the mercy of the elements, the earthquakes and the occasional Assad and Russian airstrikes that continue up north, or to live in the shadow of international sanctions that cripple the parts of the country that are firmly in Assad’s grip. In the absence of something like a Marshall Plan to rebuild what has been destroyed (mostly by the Assad regime and the Russians), what seems to keep Syrians hopeful is some patched-together idea of moving forward to something that resembles the past, but worse. Yet, somehow, within this context, people still want to get married and start a family, imagining that they will manage to emigrate someplace that will allow it.

Eventually, the mukhtar told the man “to go process such paperwork in the ‘reef,’” referring to the rural provinces.

“But when I go to the courthouse there, they tell me to come here,” the man objected, still keeping his voice soft and meek.

“So go to the provincial courthouse — just down the street,” the mukhtar said, referring to one of many rural municipalities temporarily relocated to Damascus. The man left without further argument. I suspected he would continue being given the runaround until he found someone sympathetic to help him.

His attention back on me, the mukhtar announced the next step in the process. My cousin and I were to go to the police precinct to file a report. He would escort us there, and because we were now “friends,” he would look out for us. “Do you have your military documents in order?” he asked my cousin. By entering a police precinct, a young man risked being drafted into the army on the spot if his documents weren’t in order. “Yes, I do,” my cousin responded.

“Are you sure? Everything is in order?” the mukhtar repeated.

“Yes, yes. I’m certain,” my cousin said.

“Good. And you?” the mukhtar said, turning to me. “Anything that might come up in their search? Anything at all?”

“Nope. I believe everything should be fine,” I said. Surely I would not have been able to enter the country if my record wasn’t clean, I figured. Surely, there were no summons outstanding for me, nothing stating that I was wanted for questioning by military intelligence, as there used to be in the past; as there still is and has been for hundreds of thousands, if not millions of Syrians. Reasons for this can be as varied as hailing from a rebellious village to being the subject of a personal vendetta by someone with the right connections.

Satisfied, the mukhtar got up and accompanied us on foot to the police precinct, located a few blocks down the street.

At the precinct, my cousin and I were promptly ushered into an office while the mukhtar stood in the hallway outside, chatting discreetly with a detective. In the office stood a couple of men in civilian clothes. I could not immediately tell if they too were there to file a police report or if they themselves were the police.

“Where did you lose yours?” one of them asked. He carried himself with the same confidence as the mukhtar. I made sure to stick to my story.

“Near here, down the street, just by the fountain,” I said. The truth was that I had no idea where I had lost it. I don’t even think I was the one who lost it. I think someone in my household displaced it, and one day it might show up during spring cleaning, lodged at the back of the closet or hiding between the mattress and the bedframe. I could not say any of this to the mukhtar because he would have had to send me to another precinct in an entirely different district, one with jurisdiction over the neighborhood in which my ID was lost, where I had no connection like my cousin to accompany me on this strange trip.

“So, by the fountain?” the man in civilian clothes reiterated.

“Yeah, just down there by the fountain,” I said, sticking to the lie. Truth-telling had long ago lost its virtue in a place like this.

“And when did it happen?” he said. “Just yesterday,” I said. Another lie. My ID had been missing for at least a year.

More ushering. More shuffling. My cousin and I found ourselves in a different office, this one farther inside the precinct, as if we were slowly being swallowed up and away from the main door, where I kept trying to linger. I did this not so much because I felt the need to be close to an egress in case I needed to run out of the police precinct or anything like that. I did it to get away from the asphyxiating stench of the cigarette smoke that engulfed the place. Yet anytime I got near enough to the main gate to smell the fresh air outside, a plainclothes official instructed me to move farther inside. He did so without giving a reason, and I did not feel the need to inquire.

But I think, overall, I was calmer than my cousin, who sat next to me in the larger office, alternating between biting his nails and shaking his leg. Two empty, unoccupied desks faced us in this room, and we both remained silent as we watched detectives come and go, dropping off documents and opening and closing drawers, as if searching for something that eluded them, even though the drawers were empty. At one point, a detective walked in and placed not one but two pairs of handcuffs on his desk, then proceeded to go through drawers. Another detective spoke on a cell phone, muttering about “lost photos.”

I looked around the room and noted its sparsity. There were no computers, no landline phones, no staplers, no paper clips and no printing paper. The floor was barren and filthy, and the walls, originally white, had accumulated a thin film of soot. A lone portrait of Assad hung on the wall, a cheap plastic frame surrounding it. The scene was typical of government buildings, where even if bathrooms are supplied with soap and toilet paper, they promptly go missing — stolen by employees and taken home or hawked on the street for extra cash. But it still felt sadder and scarcer than in the Syria I had known in years past, more frightening, especially because the difference between the haves and have-nots had become so much more pronounced. Earlier in the day, I saw in one city block what captured the entire mood of postwar Syria. A man was walking his pet chihuahua, which was dressed in a dog T-shirt, while a grandmother dove in a dumpster, looking for a bite to eat. A young woman walked down the street showing her midriff, which had a blingy bellybutton piercing, while an elderly man, blind and bow-legged, panhandled. They all ignored each other, as if the new Darwinism of a government preying on citizens and the poor feeding on the refuse of those barely scraping by while toy dogs shit in the street wasn’t an unsettling reminder of how the country has turned into a chimera of itself.

Back at the precinct, there were more comings and goings. Some time passed and, before we knew it, a detective produced the document I needed in order to proceed with my lost ID application. I couldn’t believe it when he handed it to me and told us we were “all done,” free to go. Outside in the sunshine and fresh air, my cousin and I breathed sighs of relief, recounting to each other the parts that were most disconcerting.

“When he put two pairs of handcuffs on his desk? I thought that was the end of us,” my cousin said.

“I know! Me too,” I answered.

Back at the Interior Ministry, we dropped off our police report and were told that my replacement card would be ready to pick up in a few days.

I left my cousin to tend to his business and decided to walk around the city to change my mood. The exhaust fumes from traffic left me gasping for air in much the same way as when I felt trapped inside the precinct, but I was in the Old City, the historic district that had always been my favorite part of Damascus. I used to come here even during the war, after the shops that sold trinkets and shawarma and local specialties like licorice juice had shuttered their doors, and the merchants who had for generations sold textiles and mother-of-pearl and spice had dwindled in number, gone into bankruptcy or exile or — like some of my own relatives — been killed, disappeared or kidnapped for ransom, never to be heard from again.

Now, the Old City seemed determined to revive itself, despite all the challenges. Restaurants have reopened, but only a few of the items listed on their menus were on offer, and even those were too pricey for someone who makes the average local income of $50 per month or so, which made me wonder why they were so crowded nevertheless. In a country that has endured a great deal of suffering, where the rubble and destruction from the war remains in place like a testament to the millions killed or displaced, and with many more on the brink of desperation, how is it that so many folk were so flush with cash that they could spend hours dining out, then go home in their shiny new sports cars? I had no answer for this, and any time I asked locals, they too seemed to shrug in puzzlement at the contradictions around them.

A few days later, I returned to the Interior Ministry and picked up my new ID, pristine and glistening. Over the years, my old ID card had taken me all over Syria — to villages and archaeological sites, beaches and mountaintops, orchards and the desert. When the war began, it took me through contentious crossings into districts with monochrome gray rubble and twisted steel, and passed through the hands of gunmen who aimed to kill each other. Where would the new one take me now? It had cost close to 1 million Syrian pounds (approximately $200) in bribes, as my cousin later relayed to me, which is equivalent to the cost of heating oil for a small frugal family to stay warm for maybe half the winter.

I was lost in these thoughts when I noticed, on the sidewalk in front of me, a thin red liquid that was running between the cobblestones, like the fresh blood of a slaughtered lamb, which would not be unusual flowing out of a butcher’s shop. I looked up at the source, bracing myself for a ghastly site, but instead I found a young man cleaning a cooler of its contents. Fresh pomegranate juice had spilled and, like everything else these days, pomegranate isn’t cheap, which explained the look of horror on the man’s face. I sidestepped the sticky juice so as not to dirty my shoes and continued on my merry way.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.