Listen to this story

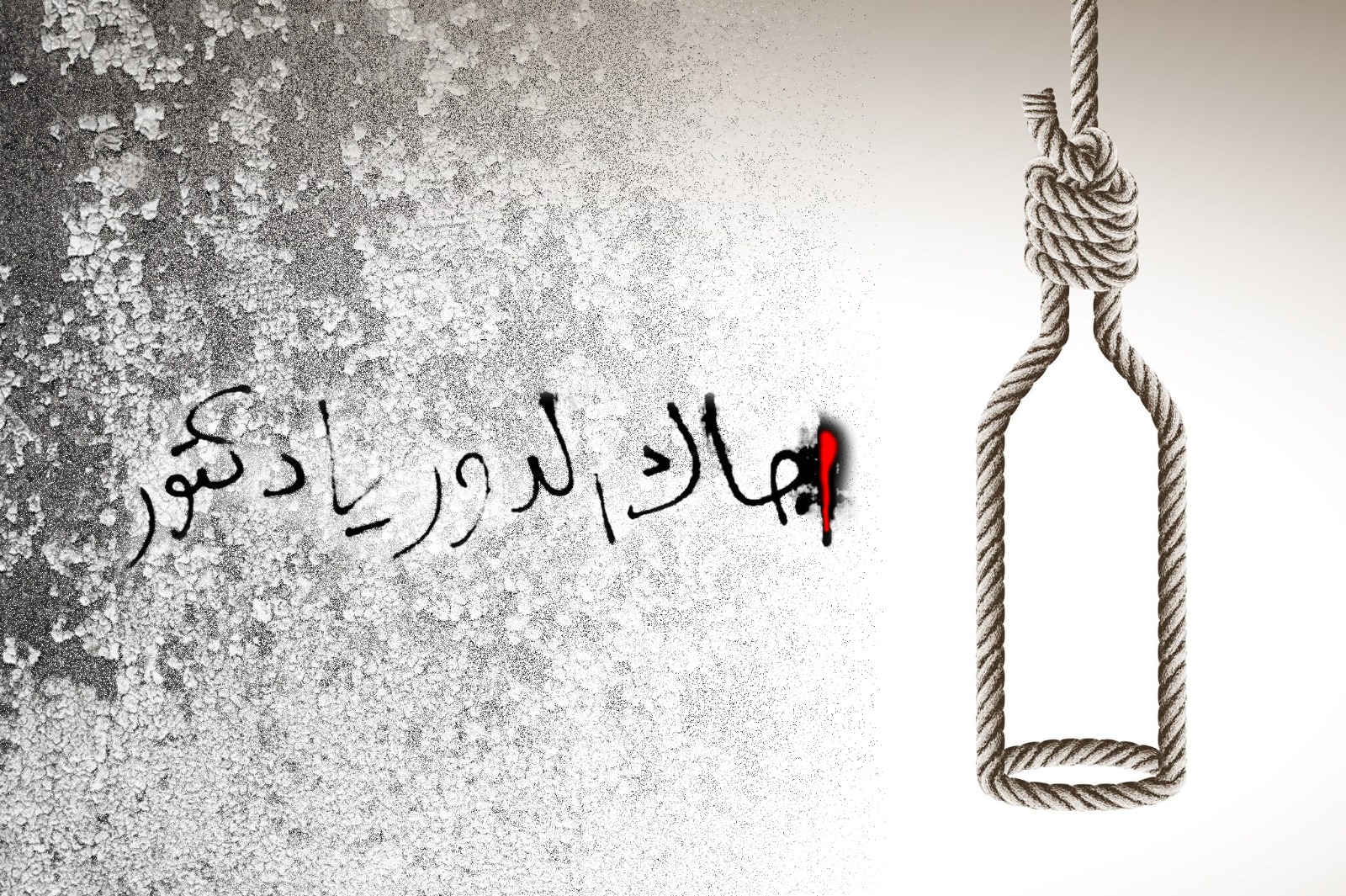

A month after jihadists had caged and beaten him using a slab of wood studded with nails that punctured and gnashed his flesh, and two years before he would affix two nooses from his ceiling — one for himself and one for his starving dog — he drank all the philosopher Sadiq Jalal al-Azm’s wine.

It was January 2013. The Fighter had arrived in Beirut two weeks earlier, smuggled across the border in the back of a car. The group of activists who had organized his escape from Syria had installed him in a small room in the Lebanese capital, dirty and crowded with others fleeing the war. “You promised me I would not be humiliated,” he told the activist who had done the most to organize his escape, over the phone. “I have no money and live like a dog.” She made some calls. Soon after, an old man escorted the Fighter to an empty apartment on Bliss Street. He told him not to leave the apartment and gave the Fighter $300 from its absent owner.

The Fighter lived on alcohol, and it emptied his pockets. The expense of Beirut, in comparison to Damascus, shocked him. Unlike the provisional dwellings filled with sympathizers to the revolution that he’d known in Barzeh, a Damascus suburb, the new apartment’s solitary grandeur bewildered him. Multitudes of books — shelved between big windows, piled beside white walls, and stacked throughout a living room large enough to be partitioned into three distinct areas — gave the space a studious tranquility. He stared at books written in languages he did not understand. He named his new home The Library.

Yet The Library offered no respite. He slept in the master bedroom and dressed in the owner’s clothes, wearing a beige jacket he would later keep. He left the apartment when the alcohol he consumed compelled him, or whenever he ran out of alcohol and needed to stock more. He left when the boredom, the static nature of passing time in an unchanging space, and the memories bequeathed by stillness, memories distant and recent, forced him outside. He took a coffee in a café on the street. He counted his diminishing funds. When he returned to the apartment, he would wander its rooms, a bottle always in hand. He leafed through the books and thought back to the school in his town, Masyaf, and of the teachers there who beat him. He thought of his father, who beat him. He remembered moments from his childhood, skipping classes with his friends and sneaking into an unoccupied villa in the forest and swimming in its pool only to find out a gardener had stolen their clothes, forcing them to slink back to town in their underwear. He counted the four books he had read in his entire life. He remained skeptical of the knowledge the volumes around him could impart.

The old man who brought him to the apartment had warned him that Hezbollah and their allies, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, surveilled it. Probably, he had noted, the apartment had been under surveillance for some time because of its famous owner. The old man said that others who had fought against the Syrian regime, like the Fighter, had gone missing shortly after crossing the border into Lebanon. Still others had gone missing weeks, even months after arriving in Beirut, leaving behind Facebook timelines full of questions and prayers. The next day, on Bliss Street, a child had passed a note to a friend of his saying the Fighter would be killed soon. The letter had been signed “The Free Syrian Army.” The Fighter had been a member of the FSA. It must have been a ruse, meant to sow discord and distrust, his friend said. When night fell and the din from revelers in the street below would build, he felt hunted. As a young man, he had been used to hunting, tracking boar or deer or birds in the mountains, with a rifle and arak (an alcoholic drink), lighting fires at night to stay warm and to keep the beasts at bay, their howls reverberating off the trees. In Beirut, he merely listened to the cackle of the crowd below and drank.

When remaining isolated became unbearable and the alcohol he stocked had disappeared, he wandered the street below. He found a bartender who took pity and let him drink for half price. The drink soothed his loneliness and his guilt and his rage and his sense of impotence. Outside the apartment, he found Syrians clustered together, laughing and crying and arguing and smoking. They relayed gossip and information gleaned from Facebook. For those who had seen fighting, temporary stability brought the anxiety of a purposeless, uncertain future, an internal peace held ransom by pills, heroin, alcohol, breakdowns, suicide, or a boat. The Fighter was no different. He drank and drank and drank until his money ran out and the days distended in unbearable monotony. He would crawl back to the grand bed in a blackout state, sleeping in his clothes.

One morning, the phone rang. The Fighter picked it up. On the other end, the philosopher Sadiq Jalal al-Azm spoke.

In the days prior to the Fighter’s departure for Beirut, his mother and sister, alongside four opposition activists, had gathered at a table in Damascus. He had been released two weeks prior by jihadists from the then al Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra (now known as Hayat Tahrir al-Shaam, or HTS). The women settled themselves around him, served tea and sweets, and sketched out a plan for his escape. He couldn’t believe he was alive and barely registered what the women said. He fixated on the details of his mother’s journey to Damascus from Masyaf. His body still ached: The lacerations opened by the blows of the nail-spiked wooden two-by-four still burned. His makeshift prison had been a cage inside a room inside a small building outside of Qabun, a rebel-controlled Damascus suburb party to various factions, each mistrustful of one another. Each night, his captors led him out of the cage and onto the building’s roof. “If a helicopter bombs the building, you’ll be the first to die,” his kidnappers told him. Now, his mother sat before him in a Damascene kitchen far from their home. Yet even removed from the cage and the daily beatings, the risk of death remained. She told him he had to leave. The FSA captain who had negotiated his release had said the same thing on their drive away from the makeshift prison.

The women around the Damascus table possessed an authority borne of age and violence. They had witnessed and understood the upheavals of the 1980s. They had been activists since before his birth. They could remember what President Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez, had done to Hamah. They understood life in the absence of heroism, recognized the appeal of transcendent death lessened with age. They confronted fear analytically, in ways inaccessible to the young. Mostly, they understood that the names of the dead would be forgotten, that they had always been forgotten. They understood that time was a tinderbox awaiting its spark. “In the future,” they told him, “you will come back and help rebuild Syria. If you stay now, you will only die.”

The next day, he crouched in the backseat of an old car and slipped across the border into Lebanon.

Almost two years earlier, in Masyaf, an Ismaili town skirted by Alawite mountainsides in western Syrian, his cousin had come running to the shop front of a small construction business owned by his uncle. The Fighter had been working for him in the isolated forests beyond the town, laying the concrete foundations of palatial mansions that would become homes for crooked businessmen. He had hunted in these forests as a boy and knew them well. He enjoyed the physical nature of the work. At first, as a 15-year-old, after dropping out of school, the work fatigued him. At 18, he had left for military service. It had made him stronger, and now he relished the work. One day, his cousin arrived breathless. “It’s started in Daraa,” his cousin yelled upwards, to the roof, to the sky. “The revolution has come!” The Fighter was 21.

A month after his cousin’s pronouncement, an army general pulled the Fighter into a dimly lit interrogation room, a light dangling above their heads like a dead body. The general offered the Fighter cigarettes. The Fighter declined and smoked his own. The general evinced a jocular menace, “I’ve heard your name connected to the shooting.” Someone had used a shotgun to obliterate the face of the Hafez al-Assad statue adorning the town square, shooting him in the dead of night from the back of a motorcycle. The Fighter had driven the motorcycle. Since his cousin’s exuberant declaration, the revolution had not sparked in Masyaf. The town was too strategically important to evade strict surveillance by a regime intent on protecting the supply lines that linked the coast with its Alawite hinterland. And Masyaf’s citizens too vividly recalled the violence visited upon them in 2005, when a fight between two microbus drivers, one Ismaili and one Alawite, had prompted Alawite gangs to descend from the mountainsides onto the town. “We are here to burn you,” they had said. For a couple of days, the police did nothing. The regime set up checkpoints, blocking traffic into the town. Finally, a truce had been reached.

After Daraa and the revolution’s outbreak, the Fighter had worked to stir the town into action. In clandestine meetings, he and a few like-minded friends from his school days had hatched a plan to destroy the monument. He drove the motorcycle on which the shooter had perched. They had filmed the incident and posted it online.

“Let us think about who could have done this,” the Fighter said to the general. He took a long drag on his cigarette. “Someone with access to guns.” A preternatural calm engulfed the Fighter. Later, he would feel fear. Now, he focused on delivering deceit in the most persuasive manner, calculating the coy meandering of his words, the stakes too high to be imagined.

“Naturally, I’m on your side,” the Fighter said. “I’m disgusted by what has been done.”

The general nodded. The Fighter’s father sat beside him, nervous yet also in awe of his son. He had brought his son to the police station after they had arrived at his store asking for the Fighter’s whereabouts. His father had long dealt with the regime, smuggling goods from Lebanon past soldiers induced by cash.

“I think I know the people who may have been responsible,” the Fighter offered. He named two brothers. He noted the brothers’ penchant for keeping weapons in their truck and insinuated the plausibility of their involvement. “I think I’ve heard their names mentioned in connection with this disgrace. You cannot trust anyone these days,” the Fighter continued.

The general perked up. Officious in his manner and limited in his intellect, he appeared eager to solve the case. The Fighter attempted to buy himself time. “Let me leave and find out where they are,” said the Fighter. “Then, I will call you.”

“If you are lying to me —” the general said, detailing various methods of torturing a body until it begs for death. The Fighter’s father knew his son would have to leave town. He sat silently, fingering his pack of cigarettes, still afraid and still in awe.

The Fighter and his father left. The Fighter located the brothers. He called the general. “If this turns out to be a ruse,” said the general. “You’re dead.”

The brothers had been informants for the government, but not for the general. Competing security apparatuses isolated their networks. Everyone kept secrets from everyone. Within an hour, an armed convoy had arrested the brothers in central Masyaf at the Fighter’s behest. He knew he had to leave. He took a gun, ammunition, and water to the forest outside the town beyond the houses of the rich. He called his father, taking pride in his ruse. “Do not mess with these people,” his father said. “They will make everyone pay for your deeds.” The Fighter could hear the admiration and agitation commingled in his voice: fear and awe.

The Fighter remained in the forest, hunting for food as he had done on trips as a teenager. He relied on the kindness of family and friends who would bring sustenance when he could not shoot enough to feed himself. He lived there for two months, shivering during the cold nights and waking without coffee in the morning. Further away, the revolution continued to unfurl.

After two months in the forest, a family friend who owned a small microbus company arranged to forge his passenger list and smuggle him out. The army had begun checking names on all inbound and outbound buses from Masyaf. The Fighter had decided to go to Damascus. He met the bus in the early morning. Crouched down beneath the seats in the final row, the Fighter peeked out of the window as the bus stopped at the checkpoint. He could see, just barely, the general himself looking over the baby-faced conscript soldier who inspected the list of wanted names. Two months in the forest had given the Fighter the look of a madman, his hair falling into long curls and his beard unkempt and wild. The young army soldier handed the list back to the driver. The bus pulled away. The general looked past the bus toward the line of assembled traffic. The Fighter could not repress his joy.

As he headed to Damascus, the Fighter called the general, who feigned paternal concern. “Where are you?” he asked. “I thought you might have noticed me,” said the Fighter, unable to repress the need to humiliate after the months of hunger and cold. “I just passed the checkpoint and saw you standing there.” The general hung up the phone. The Fighter yelled to the front of the microbus, “I need to be let off.” The microbus pulled over on the side of the empty highway and the Fighter moved off the road, hiding behind the brush. He heard the whoosh of three army jeeps speeding down the highway. After a while, he emerged and hailed a taxi to Damascus.

In Damascus, he moved houses. His friend, who had left Masyaf some years earlier, offered him a couch. After a couple of weeks, the friend was arrested in a raid. The Fighter moved in with the family of another friend. People disappeared without warning: Some returned, others did not. Of those who returned, many never spoke of what happened, avoiding their old friends. The Fighter attended protests, shouting jubilant slogans amidst the cacophonous crowd, capable, at any moment, of unifying into coherent exhortation. They gave voice to the exuberance and frisson of the collective, assembled and confident in its cause. He danced arm in arm with fellow Syrians — Alawites, Ismailis, Sunnis, Kurds, Christians, atheists — a great mass of colors and ages and accents and types. He ran when snipers opened on the crowds. It was ecstasy.

He found work at a fancy restaurant in the Bab Touma neighborhood of Damascus. High-level regime figures ate their meals within its interior courtyard. He performed security, patting down people he recognized from television. His Masyaf accent, indistinguishable from the Alawite accent of its surrounding mountains, became his passport. One day, on a cigarette break 30 paces from the restaurant’s doors, a woman with green eyes stuck her face outside of a second-story window, and they began to speak. She had come from Deir ez-Zor to study Spanish Literature. She lived in a dormitory rented to female students. After work, he would sneak into her dormitory. Amidst the lovemaking, they spoke of revolution. “I am with the revolution. But look where we are,” she would say, gesturing to the world outside the window.

He parried requests for his identification card from the restaurant manager with jokes and phrases picked up from shabiha slang, tokens indicating membership in the anti-revolutionary cause. There could be no better ID. His proximity to Syrian government officials, spending thousands of lire on dinners with their wives and children in perfectly pressed clothes, led him to plot in his head. He watched the families eat and spent days planning to kidnap them and take their information. If you cut off the head, the rest of the body will die slowly, he thought. He needed to work with others.

As the Fighter plotted, the protesters began to return fire. The revolution had armed itself. One evening, his boss demanded his ID and would not let him squirrel out with a jab and a joke. He told him he would go home and get it after work.

He left for Barzeh the next day.

Barzeh, a suburb north of Damascus, welcomed him as it had welcomed others intent on overthrowing the regime. He had slept in a public park for two nights before being brought to a farmhouse owned by an old man who could not understand why the revolution had not come sooner. Later, at the behest of a group of young protestors who organized lodging for the newly arrived, he moved into an apartment and ate by the grace of others. The conservative town accepted the young protesters with equanimity. The drinking and dance and sex that gave release to the tension of their days coincided without conflict with the daily prayers of the religious. Differences existed in a suspended state, giving way to new formations based only upon attitude toward the regime. When not protesting, he would ask townspeople how he might be of assistance. They asked him to watch their children as they performed errands. He offered them classes in drawing.

When he moved to Barzeh, he asked the young woman from Deir ez-Zor to break up with him. “It’s too dangerous. I can’t come to you. You can’t come to me,” he said. “No,” she said. “I’ll come.” She would journey back and forth on a route that became ever more dangerous. Barzeh had two halves. To the west, farms dotted the countryside where FSA fighters operated with relative impunity. To the east, beyond the street running beside Tishreen Military Hospital, remained the areas of regime control. He settled in a flat with four other activists. They were all students at university, studying literature, engineering, or medicine. They were Alawite, Sunni, and Christian, but mostly they were indifferent to religion. They would gather and speak of future days, made blissful by the drink and hopeful by the company. The young woman from Deir ez-Zor would come to spend the night.

Introduced to an ex-army officer who had organized a group fighting under the umbrella of the FSA, the Fighter offered his assistance. At first, he organized medical supplies, either donated by sympathetic doctors or stolen from government hospitals, and transported them to various staging grounds. Soon afterwards, a cell of FSA fighters tasked him with camerawork. He would film defectors declaring their allegiance to the revolutionary cause. As 2011 turned into 2012, the defections grew. The regime would tell the families of those abandoning the Syrian army that their relatives had died or had been kidnapped by rebels. Sometimes the regime claimed defectors had been discovered as traitors and detained. He uploaded the videos onto the internet, attempting to boost rebel morale through the continual advertisement of new defectors. He hoped the videos would reassure family members of those who joined the cause. Trust became currency.

He would spend his nights between his apartment filled with university students and with FSA fighters, watching movies, drinking, cooking. As his skills grew, the FSA group with whom he worked asked him to videotape their missions in order to showcase their courage and strength. He became known for his daring in operations and raids with the FSA in Damascus, Barzeh, Qabun, and Harasta. He adopted a nom de guerre: Abu Kefah. He heard a bullet fly past him for the first time.

To move between Damascus and the rebel-controlled portions of Barzeh, individuals ran zigzag across Tishreen Hospital Street in order to avoid sniper fire from the hospital’s rooftop. Every person disappeared, tortured, or killed gave purpose to the Fighter’s convictions. There was no time to mourn, only plot and avenge. It wasn’t particularly intellectual, this conviction. He could express it only in platitudes, metaphors of life against the steady accretion of death. Walls with ears had closed mouths and eyes. Parents, forced to lie to their children, to denounce the just, to praise the grotesque, to debase and humiliate themselves in front of tiny, innocent eyes that watched and understood the commingling of cowardice and fallibility. Abu Kefah fought for them — and for himself. Because fighting offered purpose and excitement and an ordered sense of right and wrong, unbounded by religion or the regime.

In September 2012, the Syrian army made a massive push into Barzeh. The night before, a mortar had demolished the balcony of his shared apartment. Everyone had awoken, their ears on fire, paralyzed. Only slowly did the screams come once the ringing died down. The missile had destroyed the balcony without damaging the apartment. Everyone shuffled downstairs.

The next day, lines of soldiers combed through Barzeh. Tanks rolled through the streets. The Fighter hid his camera — filled with videos of defectors beside photos of himself and his girlfriend — in an abandoned building. The apartment split up, two activists heading down one street and the other two with Abu Kefah in the other direction. The three of them walked the streets, attempting to sneak out to the farms beyond the city without confronting the oncoming soldiers. Turning, they walked into a detachment of 40 soldiers. “Hello,” Abu Kefah said to them. “Anyone have a light for my cigarette?” The young soldier at their head, surprised, reached into his pocket and offered a light. Abu Kefah offered his Masyaf accent, “May you be successful.” The soldiers let them pass. When the army retreated after its foray into Barzeh, unable to marshal enough soldiers to control the town, he could not find his camera.

In this period, Abu Kefah lost the remnants of his rudimentary religion. He had always mistrusted authority poised upon tradition. As a boy, his Ismaili identity had furnished excuses for fistfights. He had bloodied a Sunni boy’s mouth over a perceived slight. From his current vantage, it appeared pointless. He had danced and chanted in squares with too many different people to give merit to any distinctions except between those who shot at the dancers and those who took their bullets. He lost respect for an older generation for whom the old categories meant things.

In Barzeh, Abu Kefah made love in the minbar of a mosque, recently converted into a medical staging ground, with another revolutionary, a Christian friend who, unlike the young woman from Deir ez-Zor, had given herself completely to the revolution. If anything approached religion, it was this. Two shivering bodies amidst mortar fire held close by an animal desire for touch. Barzeh had experienced particularly heavy shelling over the day, continuing into the night. They had been moving medical supplies into the makeshift hospital together, carrying tourniquets and bandages and painkillers around the bodies of the wounded. Later, the young woman from Deir ez-Zor could not understand that in moments where death surrounded everyone, seeped into every pore and hovered beside the cries of the injured laid on beds awaiting death or recovery, cries anticipating and mourning time’s handiwork, his need for physical intimacy balanced the need to evade death. War brought truth to the clichés. To die in someone’s arms, in that moment, seemed to him an outcome acceptable, if not desirable. In some ways, though, she had understood perfectly well. When he had told her in his matter-of-fact manner of his betrayal, she had crossed from regime territory into rebel territory in order to scream as mortars fell in the evening.

“If you do not understand,” the Fighter had said, “then we cannot be together.” The ordnance fell like thunder before rain as she stood in his apartment. She stormed back onto the street intent upon returning to Damascus. “It is too dangerous to return tonight,” he said. “I am ready to die,” she said, marching away. He could feel the cross of sniper scopes dancing on his back. Her melodrama unnerved him. He ran up to her and hit her, hard, in the face. She fell, stunned. “You are a child and if you do not come back to the apartment now, you will kill us both.” He dragged her back.

Abu Kefah found her courage, cloaked inside her rage, unendingly beautiful. A child’s courage, he thought. Jealousy provoked unimaginable bravery, preserving individuality in the idiosyncratic and ignoble emotions of everyday relationships that kept one sane in a crumbling world. They were children together amidst the ordnance.

Abu Kefah slowly developed a plan. He would mimic the regime in order to destroy it, undermine its intelligence apparatus by hunting its informants, kidnapping them, and interrogating them. They would tell him who they worked for and what they knew. He would slowly move up the chain of command, destroying sources of information until the regime became blind. It would begin at the lowest levels and work upwards. He approached the ex-military officer, who had survived the regime’s onslaught in Barzeh. In the days since he had first tasked him with holding a camera, the soldier had gained his trust by never holding in contempt Alawites who stood with the revolution. “This regime will never fail through armed operations,” Abu Kefah told him in a speech he had rehearsed. “And it won’t fall through protests. They will kill us all in the squares. We must hunt them like they hunt us, take little bites from the whole.” Abu Kefah explained how he would move into regime areas, using his accent as a passport, convincing low-level informants that he worked for the regime before organizing their abduction. He needed a car, some guns, and some people. Abu Kefah enjoyed the tidy unfurling of logical steps, the steady work of moving upward along a chain of intelligence in order to undermine the regime’s tentacles of control. He spoke about it as a grand plan, a mission capable of destabilizing the regime, cutting it off from what it required most, the ability to distinguish between those who wished its destruction from those either too afraid or too apathetic to work against it. “I can hunt this regime,” he said.

The ex-army officer trusted him enough to arrange it. Abu Kefah began with Damascus taxis. The regime had gifted a series of cabs to individuals who had proven themselves against protesters in one way or another. In exchange, those taxi drivers had been given instructions to question their passengers in roundabout ways and to deliver anyone who appeared suspect to the various agencies comprising the mukhabarat (secret police). The drivers, in exchange, kept their earnings from the cab. Abu Kefah began operating in certain neighborhoods in Damascus. He approached taxis that took long breaks on side streets or lingering at kiosks, knowing that the drivers working for intelligence did not need to pay off their car loans, knowing that brutality and laziness often coincided. “Min jay jihatna,” he would say by way of introduction, using a shorthand expression to identify himself as regime affiliated. They would strike up a conversation. “I’m from Masyaf,” he would say, letting the driver assume his politics. The talk would begin slowly, deliberately. He would enter and give directions to a street where the team had planned to assemble in Barzeh, waiting in stolen regime intelligence cars. Abu Kefah had seven minutes with the driver before he would have to tell the team whether to be prepared. They would gather on the eastern side of Barzeh.

It all lay in making the driver feel a sense of security. He would sidle into the front passenger seat and cosset their feelings with observations, jokes, a targeted complaint they would find apt. Then, finally, Abu Kefah would offer, “Between us, I am an Officer for Regime Intelligence.” Sometimes, the cabs would take the bait. “Me too,” the driver would say. “Really?” Abu Kefah would ask with a smirk, evoking circumspection. He would begin to detail some imagined operation against revolutionaries, watching the driver’s response. He would marshal his arrogance, provoking them, “You haven’t done anything for our father, Assad.” Those who fell would fall hard. One driver replied, “I have killed tens of protestors for our country.” Their stories would unfurl. Abu Kefah would listen intently, attempting to decipher the boasts from the truth. The particulars mattered. He understood the innocent, cowed by the situation and fearing the appearance of apathy, might overact, might expand, might lie. If they convinced Abu Kefah, he would send an empty WhatsApp message to the group organized by the ex-soldier. If he received an empty message in reply, it meant the team was on its way. A second empty message indicated the team had arrived. Once the driver arrived at the meeting point he had been given, three cars would jam him — one in front, two behind. Abu Kefah would take the key from the ignition. The front car would evacuate two members of the armed team, grabbing the taxi driver and bringing him inside their vehicle.

At this point, the tenor would change. They would bring the man out to the farms, to a nondescript building nicknamed “Abu Ghraib,” controlled by affiliates of the FSA. Abu Kefah would play judge. “Listen,” Abu Kefah would tell the driver. “We are the Free Army. I am intelligence, but not for the regime.” He had practiced the speech and relished its delivery. “But I am also Alawite,” he would lie, offering them a hint of solidarity. “Tell us everything you know: Who is like you? Who gives you orders? Who are the officers above you?” He would offer them a cigarette. “We will balance the crimes you have committed with the information you offer. With enough information, we let you go. If the balance is even, we’ll hold you in a cell for a time. If you tell us nothing, you are fucked.”

There was one rule: no torture. The most important thing, he understood, was to convince them he was Alawite, and that revenge would not be taken by virtue of sect.

There was one rule: no torture. The most important thing, he understood, was to convince them he was Alawite, and that revenge would not be taken by virtue of sect. He needed them to think rationally, to understand the merits of the transaction. Once they accepted that Abu Kefah controlled their lives and offered a fair exchange, most of them spoke. Then, they would be confined in the “jail,” a small house with a garden under observation nearby, before being let go a few weeks later. In the meantime, their information would travel to the ex-soldier, then to his boss, and finally upwards to people Abu Kefah never met.

Abu Kefah captured 10 intelligence officers this way — some normal shabiha (state-sponsored militias), some working for army intelligence. He became known in Barzeh. The continual streams of information coming from Abu Kefah’s methods rendered him a figure of note. The ex-soldier came to appreciate his usefulness. He turned 22.

In his apartment, the university students would challenge his decision to get more involved with the FSA. “The regime is getting more violent because we are,” one activist would say. Abu Kefah remained unimpressed, countering, “If we protest, he will kill us all. You will die alongside your beautiful words. We are all one, you say. But we are not all one. We are brothers, you say. But we are not brothers. They will eat you and your words.” He remained frustrated by their inability to understand. “If you hold a gun against him, you will take a hundred even if he kills a thousand of us. I come from the heart of the regime,” he would say. “You come from Damascus. Go fuck yourself.”

The university students believed in justice. They did not believe it existed inside Syria, but they believed it could be imported. Abu Kefah regarded them as children, filled with the ideas of children who spent all their time in schools, debating propositions without meaning. Their books taught them fantasies. “This is a country where you can get away with anything: stealing, rape, murder. Everything except politics,” he would tell them. He had seen it in Masyaf growing up. He had seen the murderers pardoned, the thieves released, and those who spoke against the system buried. He understood justice had no meaning. He felt those with whom he lived had become addicted to their ideals just as the regime had become addicted to its tyranny. Later, when three of them died under torture, he could only pity them, the knowledge learned too late.

The sun began its descent over Damascus. Inside the taxi, the driver spoke. “I work for the regime,” the driver said. “I work in an office. I don’t really care about the street.” He let out a sigh, “But of course I love Assad.” The driver looked silently out the window as the car stood at a traffic stop, tossing his cigarette onto the street. He preferred to speak of his sons, not this miserable situation. He sounded tired. His words possessed no enthusiasm. To Abu Kefah, he sounded like the thousands of men and women who lived in the mire of daily life, compromising to eat, compromising because poverty rendered principles pathetic. His honesty confused Abu Kefah. Accustomed to the games, the subtle tics, the innuendo, Abu Kefah sat confronted by beleaguered, beaten down honesty. “I don’t give a shit about it,” the driver said. “But I do it.” Abu Kefah delayed. The driver was courting risk. Why did he dismiss the regime’s motives if he thought Abu Kefah worked for them? Maybe he suspected Abu Kefah? If the driver was honest, he reasoned, he would interrogate him and then let him go. Perhaps the man’s fatigue only covered his malice, his treachery, his dishonesty. Perhaps the driver manipulated Abu Kefah. Abu Kefah sent his empty message. The ex-soldier sent back a message, “We are in X. We cannot come.” Abu Kefah replied, “Send me some other people.”

A few minutes later, Abu Kefah received an empty message from an unknown number. He received another. As they approached their destination, three cars began to tag the taxi. The driver became anxious. One of the cars pulled in front of the taxi. The driver’s eyes darted from the front car to the rearview mirror. His reaction confused Abu Kefah. It was too quick. Abu Kefah directed him into an alley. The driver stopped the car and began to reverse in the opposite direction. Abu Kefah protested. The trailing vehicle sped backwards alongside the taxi, cutting it off.

The driver’s sense of danger exploded. He rammed the taxi backwards into the vehicle. Abu Kefah reached for the keys, grasping, and finally turning the ignition off. A group of men exited the front car and began firing at the driver. “What are you doing?” Abu Kefah yelled at them. The men were amped up, excitable, violent. The driver jumped out and was shot in the thigh. He fell to the ground. The men grabbed him and pulled him into one of the cars. Abu Kefah could not find reason in their eyes. They brought the driver to the makeshift interrogation room. His bleeding had staunched. Abu Kefah looked at the men around him. He didn’t recognize a single one.

He began the procedure. Cognizant of the man’s pain, he stumbled through the terms. His voice lacked its normal assurance. He spoke volubly to ward off the men around him. They lurked in packs like wolves around the wounded driver, spitting names at him.

“Do you understand?” said Abu Kefah.

“Yes.”

“Where are you from?” Abu Kefah asked.

The driver trembled, holding his leg. “Salamiyah,” he choked out.

The information amped the men behind Abu Kefah. “Ismaili dog,” one said. He realized the man’s mistake immediately. The men behind him had their information. The driver had told the truth, part of the exchange, and had signed his own death sentence. Abu Kefah tried to quickly ask his next question, but the men shoved him aside. Outnumbered, he watched in horror as they began to torture the driver. They beat him with unrelenting viciousness, laughing as the impact of metal pipes against skin elicited ever-diminishing twitches from a body losing its mind. The man emitted the sounds of a form reduced to sensation. “Infidel dog,” they cried.

It became clear to Abu Kefah that the driver would die. That the men into whose hands he had delivered him would kill him with relish. That he had lied to the man. That there would be no fair exchange. It would be a pointless death: A death by virtue of sect, by virtue of bad luck. The ugliness of arbitrary fate disgusted him. Abu Kefah began to tremble. He fought a losing battle against the men. “This is not how this works,” he yelled. He tried to retain a certain confidence, but it faded with every blow against the driver’s body. They looked at him unknowingly. They looked at him with menacing bemusement, like he was a child. “What are you fucking doing? I do this job.”

“Fuck off,” they told him. “You’ve done your part.”

They shoved him away from the driver. “Keep the taxi,” they told him.

Abu Kefah tried to reason. “We know nothing about him.”

“Why do you worry about him?” said one of them as he shoved him away. “He’s a dead kafir.”

Abu Kefah strained to see over the man who shoved him toward the door. “I’m an Ismaili also,” Abu Kefah said. “Why are you doing this?”

He forced his way to the driver. The man quivered on the ground, rasping and breathing like an asthmatic. Skull protruded through his torn scalp. Abu Kefah could see his brain. The driver began to crawl, uncoordinated, seizing up. He would die, Abu Kefah was certain. Abu Kefah tried to imagine what the man would want: either to escape or to die. It was too late for escape. Rage and anger and sorrow and despair engulfed him. The man gargled. Abu Kefah picked up a gun lying on a table, grabbed the man by his neck, looked away, and shot him in the head. Blood splattered onto his arm. The man fell slack onto the cement floor.

Abu Kefah lost it. Gnashing and yelling and crying, he picked up the body and brought it outside and put it into the taxi. Night had fallen. He sped down Tishreen Hospital Street past the education center where they taught nothing, past the hospital where they cured nothing, past the buildings with snipers arrayed on top. Abu Kefah turned on his headlights, speeding down the pockmarked and desolate road, keeping the interior car lights on, asking for a sniper to shoot. No one did. No one seemed to register his presence.

He took the body across Barzeh north to the farms in order to have it buried. Later, he held the same gun to his temple and wondered, not for the last time, whether he could kill himself. But even a gun at his head could not remove the image of the driver’s children, sitting at home and wondering why their father was late.

Later, the ex-soldier asked him to explain what had happened. “I killed an innocent man,” said Abu Kefah. “The people you sent are criminals.”

“It’s not your fault,” the ex-soldier said. “It was my fault.”

Abu Kefah could not stifle his cries, “I’m nothing more than a criminal.”

“He may not have been innocent. You could not ask him anything. You didn’t have time.”

Abu Kefah stared back. “He’s innocent because he didn’t have the chance. I have murdered my own principles.”

In an apartment in Damascus, he lay on the floor next to the most beautiful woman he had ever seen. He had begun to take more risks. He had stopped her earlier in the day on the street. “What do you do?” she asked. “The Revolution,” he said. “I work for the revolution.” The woman loved someone else, a married man. They walked the streets of Old Damascus. Passing a boutique, he bought her a dress with all the money he had in his pocket. Later, she took him to her room, and they lay awake beside each other through the night. He regaled her with stories of the revolution. She egged him on. He relished her attention. He unspooled the stories in a slow, deliberate manner, eliding certain events, exaggerating others. He mapped the world in ways that made sense. She put on the dress he had bought and stood above him as he spoke. It felt better than lovemaking.

The following evening, Abu Kefah got a call from the ex-soldier. It was the end of 2012. “We need you to record an operation. My boss called me asking for you.” Abu Kefah strained to hear him over the protest in Rukn al-Din.

“We need you,” said the ex-soldier. “It’s going to be hell.”

Abu Kefah left the protest, where men and women, girls and boys, danced together shoulder to shoulder, yelling: “Oh Syria, oh Syria, your voice is loud, oh Syria, it shakes the presidential palace.” He left his friend in Damascus and headed to the farms of Barzeh, skipping over Tishreen Hospital Street, past the familiar clack-clack-clack of sniper fire, lazily registering his presence, to meet the team at the address he was given. He knocked.

Three Jeeps pulled up outside the building. “Abu Kefah!” someone yelled from the car.

“Hello!” said Abu Kefah in the darkness.

Someone hit him on the head and grabbed him. They shoved him into one of the cars and covered his eyes with a hood. Confused, breathless, he focused. He knew the area well and followed the cars’ directions: east, east, east, past Barzeh, into Harasta, into Qabun. He became afraid. He knew no one in Qabun. The car stopped. The door opened and he felt an iron pipe slam against his body. He felt a wood stick slam into his body. He could hear someone, further away, accuse him of working for regime intelligence.

They shoved him into a building.

Betrayals are petty affairs, he would later learn. An army defector, shy and quiet, had approached the FSA in Barzeh a week prior. The defector had been required to forfeit his electronics and to remain under observation for a week. For a period, Abu Kefah had been tasked with watching him. The man’s girlfriend had come and given him a phone. The defector had asked to send a text to his parents. This broke the rules, but the rules were always being broken. The defector, greedy and begrudging, had sent a series of texts to his own parents, claiming he had been kidnapped and requesting they send 1 million lire to his bank account. He told his parents the kidnappers had his debit card. He told them he would be killed unless they sent the money. He signed the messages, “Abu Kefah, Barzeh.” It was a fate of irony, Abu Kefah would later recognize. He had never owned a debit card or possessed a bank account in his life. As he danced in Damascus, word had spread. A Jabhat al Nusra affiliate, one of the militias operating within Barzeh, enraged that the militias would appear venal, had organized the snatch.

Barzeh had changed. Hezbollah had arrived. Jabhat al Nusra had arrived. Militants from other parts of Syria, radicalized and stronger, brandishing new weapons and seemingly endless funds, began to dominate the loose-knit FSA organizations. In the weeks prior, Abu Kefah had been told by a dejected FSA commander trying to explain the internal military politics that had led to the newer militants’ incorporation into the organization, “Better that a dog barks for you than at you.” Yet the scrappy but disorganized FSA had continued to cede ground to men like those who had tortured the driver. Men who spoke differently and invoked God too frequently.

They kept him prisoner in a 2-square-meter (79-square-inch) cage within a room and beat him. For four days, Abu Kefah expected death. When they left him alone, Abu Kefah could see a table with bombs arrayed upon it at the far end of the room. One of his guards would approach him every few hours, “Don’t forget my face. I am the last person you will see before I put a bullet through your eyes.” Then he would leave Abu Kefah alone.

On the third day, he asked to pray with them, attempting to showcase a religiosity that might evoke their sympathies and give him time, in the space from the cage to the prayer room, to grab and somehow detonate one of the bombs, killing them all. As they moved him to the prayer room, a pointed rifle tracked his movements. He couldn’t sleep. “Al-faram,” they would call him, something chopped into pieces. One man, whom Abu Kefah called The Slave, brought Abu Kefah bread every day. On the third day, he told The Slave, “Tell them in Barzeh I am here. Tell (the ex-soldier) in Barzeh that I am here.”

He had been isolated like this once before. During military service after he turned 18, he had undermined a commanding officer on two occasions during training in Al-Mazzeh. After the second time, the officer had put him in solitary confinement for two weeks. He shared the room with rats. The guard spit in his food. After his release, his fellow conscripts spoke of him as a hero. When his insubordination did not cease, the officer had him lay out on a highway in the summer heat, the asphalt burning his entire back. He could not move for a couple of days afterwards. He learned to be silent.

Abu Kefah never understood why his captors did not kill him. Perhaps because they wanted to trade him to the regime. Perhaps those who knew him had worked to protect him. Perhaps because even they were scared. He knew he could not convince them. They were radicals, true radicals, different from the fighters he had known. Harder, unrelenting, colder, and more certain.

On the fourth day, Abu Kefah heard a series of shouts from outside the building. The group of men, maybe five or six, who had held him stood behind the door. “Who is there?”

Abu Kefah heard the ex-soldier shout through the door.

“What do you want?” said his captors.

“We have a friend here named Abu Kefah. Let him leave.” The ex-soldier threatened to fire on the men.

The head of the group holding him captive exited the building. He went by Amir. “Are you crazy?” he said. “You and us, we’re Muslims. Brothers together. You want us to kill each other over some kafir working for the regime.”

The ex-soldier stood his ground. “I will happily kill Muslims like me to free this kafir.”

Abu Kefah rallied. He yelled out to his friends beyond the door. To his mind, it unfolded like a melodramatic theater performance. Everyone performed speeches with varying degrees of feigned fearlessness. Without the live ammunition, it would have been pathetic. He watched these men, armed to the teeth, fumbling for things to say, his life in the balance, and it all felt very far from the purpose. He yelled again.

Amir, disgusted, eventually opened the cage and let him leave. Abu Kefah hugged his friend and wept. The ex-soldier looked at him, “We don’t know who’s in Barzeh. We can’t protect you anymore.” For him, Syria had come to an end.

He left the farms and spent 14 days in Damascus on a friend’s couch. Through a chain of contacts, his friends put him in touch with older activists who could smuggle him out. His mother, his sister, some friends, and some people he did not know gathered around a table in Damascus and planned his escape. They found a driver to take him across the border to Beirut. Eventually he came to the grand apartment on Bliss Street, owned by a man he had never met but who nonetheless offered him his home.

In Beirut, after he had emptied his pockets on drink, after time passed in ways distended and contracted, the phone rang and the older owner, warm and confident and compassionate, encompassing the jurisdiction of wide thought and ponderous resignation, chastised the Fighter and exhorted him to be careful.

“Do you have enough money?” the Philosopher Sadiq Jalal al-Azm said.

“I’ve spent it all.”

“All of the three hundred dollars? On what?”

“On alcohol.”

The Philosopher let out a curse and directed him to a tall cupboard with polished wooden doors beyond the reams of books littered everywhere within the apartment. He described the location of the key that opened the cupboard. The Fighter, wireless telephone in hand, opened it. Beyond it lay vodka, whiskey, wine. Beautiful bottles behind beautiful bottles behind beautiful bottles.

“I will send you some more money,” the Philosopher said. “Drink this instead and watch yourself.” With this admonition, the old man hung up. They never spoke again.

Later, he would fashion a noose from rope and tie it to the rafters of his apartment in Cairo. He had left Beirut when it felt too dangerous — reprisal too easy and common, the border too porous. He had come with five other Syrians to Egypt as the world’s borders tightened around them. They hated Cairo. The heat, the contempt for Syrians, the dialect, the failing revolution, the arrogance of an impoverished society clinging to its past, the pollution, the inability to breathe, the unemployment. After two months, his compatriots had tried to convince him to return to Syria, convincing themselves in the process that it would be safe. He refused. Four of them bought plane tickets and flew back to Damascus; they would tell the regime they were done fighting. When they arrived in Damascus, they stopped responding to texts. Months later, the regime notified their families of their deaths. When he heard about it from Facebook, he fashioned the noose. Then, he fashioned a second noose for his dog, abandoned by its past owner and adopted by the Fighter. He called it Andy. The dog looked upward at him with eagerness, without comprehension. He sat under the nooses for a long time, smoking. The dog lurked around him, nestling its head into his side. He took the nooses down.

Later, he would not leave his apartment in Cairo for a year. A girlfriend would bring him food. They fought because she could not understand. She grew tired and left. Afterwards, friends would bring falafel or fuul from the street or, when they could not stomach his despondence, put it in a basket he would lower from the fourth floor of his Abdeen apartment. He watched movies, smoked hash, injected heroin, swallowed a tramadol every couple of hours, mixing it with any other pills he could get delivered. He drank endlessly and struggled to sleep for fear of his dreams. He would scan the street from his balcony and imagine his head deformed after impact with the pavement.

Later, his parents would call and ask him for money, telling him they were starving. “What money?” he would say. “I gave everything for Syria. I gave my life for this terrible country and now you want money. Do you think I live like a king?” His residency card had long since expired. He worked odd jobs under the table in Cairo. He made money renting out rooms in his flat. He lived month to month, borrowing from friends. He screamed at his parents, blamed them, abused them. He recounted his father’s beatings in detail over the phone. He stopped talking to them.

Later, he would begin to sculpt. He would put on the beige jacket he had stolen from the Philosopher’s wardrobe. His initial statues transformed before his eyes into a grand project. He sketched eighteen figures from ancient Syrian myths, surrounded by smaller figures of the same deities in colors meant to represent a trinity of human emotions: anxiety, fear, and horror. The Artist bought a notebook and wrote down his meanings, scribbled and refined in Cairo cafes in between planning his sculptures.

“I think that anxiety, fear and horror are a group of feelings that are linked to one another. In many cases, we can describe this interconnection as familial. Anxiety is the oldest of them, followed by fear, then horror.”

He continued, “Anxiety is term invented to explain a specific type of nervousness. However, human nervousness expands until the word has no meaning, and instead of people addressing their worries, they create a new term: fear. This term attempts to contain what ‘anxiety’ could not. Overtime, fears accumulate, and instead of people resolving their fears, which had previously been mere worries, they created the term ‘horror.’ This term tried to explain what the term ‘fear’ failed to explain.”

He continued, “Beginning with the idea that people fear what they don’t know, and the fact that survival is closely connected to knowledge, anxiety would appear to be the main driver of knowledge. Thus, humanity’s existential questions guide them to answers, and when they find answers, they become reassured. Reassurance being the same thing as not being nervous about survival. However, people do not always find final answers to their questions. This can lead to increased anxiety, and each time anxiety increases, fear appears. Fear necessitates protection, and each time protection is sought, horror appears. Each time horror appears, signs of contamination increase, and each time these signs of contamination increase in number, so do the signs of the loss of control over it.”

But all this came later, in an unresolving future. For now, in Beirut, before Cairo, after Syria, Sadiq Jalal al-Azm offered his wine.