Poetry is ubiquitous in Iran: It is on tombstones, human skin, walls, cars, shirts and social media biographies. Carpet makers weave couplets into rugs, and artisans etch them into jewelry. Weddings, funerals and religious services would not be complete without a poetry recitation, and much of Iran’s popular music is classical poetry set to traditional and modern instrumentals. Nearly every home has at least one dīvān (collection of poetry), placed next to the Quran to signal its significance. Iran lives and dies by poetry.

Notwithstanding their educational attainments, Iranians readily decorate their daily speech with aptly quoted poems. Frustrated by the economy, a taxi driver recites: “When the lord of a village is unjust / become a beggar, every farmer must” (cho nākas beh deh kad khodāī konad / keshāvarz bāyad gedāī konad). At the graveyard, a mourner eulogizes: “I’m not from this dirt world, I’m a divine bird that once flew / they made me a cage from my body for a day or two” (morgh-e bāgh-e malakūtam, nīyam az ālam-e khāk / do seh rūzī qafasī sakhteh-and az badanam). Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, reminding listeners that Iran’s success or failure against its adversaries is decided by God, quotes: “If they all draw their blades to kill / a vein’s not cut without God’s will” (agar tīgh-e ‘ālam bejonbad zeh jāy / naborad ragī tā nakhāhad khodāy). The Supreme Leader is a poet; he also hosts poetry readings, a tradition dating to the emergence of Islam in Iran. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of Iran’s Islamic Republic, was also a poet and left behind a large dīvān.

When Iran was threatened by ISIS, Iranians wrote war poetry: “We stand swords in hand and shields at our side / because this tribe has a leader and guide” (īnkeh mā dast beh shamshīr o zereh īstādehīm / sabab īn ast keh īn tāyefeh rahbar dārad). When the nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was assassinated, Iran’s foreign minister tweeted, “Tell the rock, we’re a perfume vial” (mā shīsheh-yeh ‘atrīm, begūīd be sang) — the glass of a vial of perfume is thick and sturdy. On the International Day of Peace, he tweeted verses from Rumi, “Don’t say, ‘What use is my call for peace when they fight?’ / You are not one, but thousands, so ignite your light!” (to magū ‘hameh beh jangand o zeh solh-e man cheh āyad?’ / to yekī nehīy, hezārī, to cherāgh-e khod barafrūz). In response, the United States State Department Persian-language Twitter account (@USAbehFarsi) replied with a Hafez couplet: “The preachers who in pulpits put on such a show / do other things when to a private place they go” (va‘izān kīn jevleh dar mehrāb o menbar mīkonand / chon beh khalvat mīravand ān kār-e dīgar mīkonand).

Even a casual observer could notice the importance of poetry in Iranian society, if only because a disproportionate number of tourist sites in Iran are the graves of medieval poets. When classical poetry has become a distant memory in so many cultures, it is clear that it is an integral part of the Iranian consciousness. But simply observing a cultural phenomenon is one thing; understanding it is another. Learning the story of Persian letters helps us better understand Iran as it is today and how it views itself, the world, and its future.

After the early Muslims broke out of Arabia and conquered two vast empires, most of the newly converted peoples were Arabized. Their cultures and languages were blended with that of the conquerors, producing the syncretic “Arab world” we are familiar with today. The only major exception to this rule were the Iranic peoples, who retained their languages and sizable parts of their pre-Islamic identities. With the collapse of the Umayyad caliphate and emergence of the Abbasids, small dynasties in Khorasan (the northeastern end of the Persianate world) began to enjoy relative independence from the central authority in Baghdad. The dynasties were mostly of Turkic ethnic origin, which would remain the case until the end of dynastic rule in Iran, but the language of the royal court and bureaucracy continued to be Arabic, following the example of Baghdad. It was in these royal courts far from the seat of power where Persian slowly reemerged as a language of recorded literature.

After the Islamic conquest of Persia, the New Persian language adopted a modified Arabic script (four letters were added to represent sounds not found in Arabic) with many Arabic loanwords. The new Persian poetry was written according to Arabic conventions, using the meters and forms originating in that language. The Turkic sultans were happy to patronize this new genre, as it served a dual function: It helped legitimize their rule over Persian speakers and immortalized their legacy in favorable terms (many minor sultans would be largely forgotten today or remembered negatively if not for the numerous panegyric odes written in their courts). The emergence of Persian poetry is a metaphor for Iran itself: part Islamic, part Persian, and totally unique.

The very first poems of the Persian canon remain mostly comprehensible to the modern reader. In a Tehran zūrkhāneh, a traditional gymnasium where ancient warrior-sports are practiced and the sports are set to the tune of a drummer called a morshid (guide) who sings classical poems, a nearly 1,000-year-old poem is recited by him:

If your debased desires are confined, you’re a man,

if you do not mock the deaf and blind, you’re a man.

A man does not kick the fallen — he gives a hand,

if you help one who’s fallen down stand, you’re a man!

gar bar sar-e nafs-e khwad amīrī, mardī

bar kūr o kar ar nokta nagīrī, mardī

mardī nabovad fotāda rā pāy zadan

gar dast-e fotāda-ī begīrī, mardī

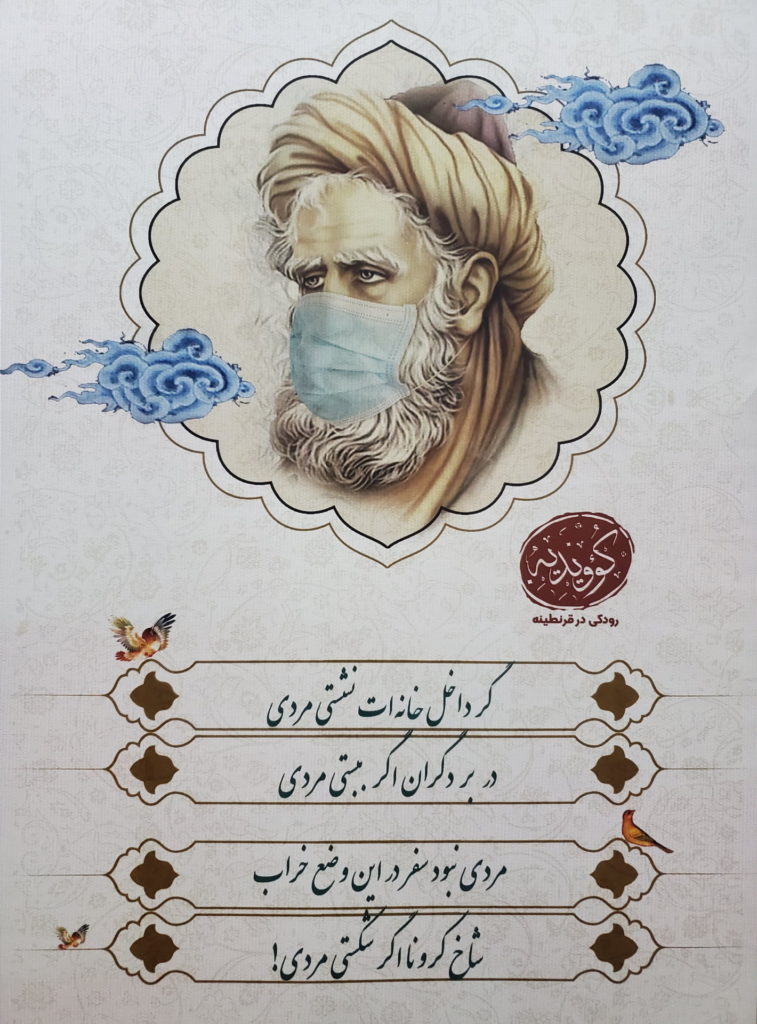

The same poem is remixed for the coronavirus pandemic, alongside a portrait of the poet Rudaki (circa 859-940) wearing a mask:

If at your home you do bide, you’re a man,

if you let no one inside, you’re a man.

A man doesn’t travel in this troubled state,

if you seal corona’s fate, you’re a man.

gar dākhel-e khāna-at neshastī, mardī

dar bar degarān agar bebastī, mardī

mardī nabovad, safar dar īn vaz‘-e kharāb

shākh-e koronā agar shekastī, mardī

The original poem is not quoted in the poster as it is assumed a literate passerby would already have heard it; both the language and the Persian understanding of manhood have weathered the test of time. This marks an important difference between Iran and the Western, and particularly the Anglophone, world. While English speakers add a myriad of foreign and newly coined words to their lexicon every year, Persian speakers are more reluctant and opt to craft local equivalents (as the French do with lesser success). Many Iranians even consider the excessive use of (particularly English) loanwords distasteful and conceited. Preserving the existing soundness and continuity of the language is far more important than carelessly acquiring foreign words. The default position of Persian linguistics is prescriptive, rather than descriptive.

These sensibilities also apply to the Iranian understanding of the past. As Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare are removed from Western curricula in favor of modern authors who address topics relevant to the contemporary reader (such as race or gender issues), Persian speakers continue to learn and recite poems of a bygone era. Their morality is found in the parables of Sa‘di Shirazi, Rumi, and Firdawsi, which are still part of school curricula and daily speech: “Don’t pain an ant who drags a grain of rice / for he’s alive and living life is nice” (mayāzār mūrī keh dāna kash ast / keh jān dārad o jān-e shīrīn khwash ast). Like other Muslim societies, Persianate peoples generally consider morality divinely revealed and static. This contrasts with the dominant understanding in the West in which morality is perceived as constantly evolving.

The concept of moral evolution by definition makes our ancestors immoral, rendering the Persian practice of consulting letters of old for moral guidance a fool’s errand. In any case, the rapid change of the English language complicates efforts to connect with the English canon. Every generation of English speakers is further disconnected from the past, both linguistically and spiritually. This was noted as early as the 17th century by the English politician and poet Edmund Waller, who lamented that Chaucer’s 14th century poetry was already archaic by his day:

“Poets may boast, as safely vain,

Their works shall with the world remain;

Both, bound together, live or die,

The verses and the prophecy.

But who can hope his lines should long

Last in a daily changing tongue?

While they are new, envy prevails;

And as that dies, our language fails.

When architects have done their part,

The matter may betray their art;

Time, if we use ill-chosen stone,

Soon brings a well-built palace down.

Poets that lasting marble seek

Must carve in Latin or in Greek;

We write in sand, our language grows,

And, like the tide, our work o’erflows.

Chaucer his sense can only boast,

The glory of his numbers lost!

Years have defaced his matchless strain,

And yet he did not sing in vain …”

In what amounts to a fulfillment of his foretelling, readers will notice that Waller’s poem is, ironically, already archaic. The changes in pronunciation have disrupted the rhyme scheme, proving his prophecy (pro-feh-sigh, not pra-feh-see). These different approaches to language and the past mark a fundamental difference between English-speaking and Persianate (and generally Islamic) societies. Iranians are keenly aware of, and deeply connected to, their past, which continues to leave a mark and affect the present.

With the rare and local exception of the recent conversation surrounding reparations for African Americans, Westerners largely view themselves as individuals as opposed to inheritors of past grievances and relationships. Every generation appears with a clean slate: Americans would not suggest that America’s relationship with Germany, Japan and Britain should be negotiated in light of World War II and the Revolutionary War. Iranians place more importance on the communal (and national) memory and consequently view themselves as inheritors of their ancestors’ grudges and friendships. When talk of renegotiating relationships with the West arises, the 1953 CIA-backed coup is invariably invoked, and Iranians similarly skeptic of Russia make references to the Treaties of Turkmenchay and Gulistan, two early 19th-century land secessions from Qajar Iran to Imperial Russia.

These sensitivities are not only found in Iran. It’s not an accident that the recent “peace” deals with Israel and some Arab states were called the Abraham Accords. A proposed Iranian equivalent would be called the Cyrus Accords, named after the Persian king lauded in the Jewish Bible for freeing the Jews from bondage in Babylon. When emphasizing the danger Iran poses to Israel, former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyanhu frequently invokes the story of Purim, when the Jews escaped the plot of an ancient Persian king’s viceroy to kill the Jews living in the Persian empire. Though Western observers mocked his rhetoric, it is familiar to Iranians, who often draw parallels between Iran’s current enmity with the Saudi state and the fighting between the Arabian tribes and the Sasanian Empire. The Saudis in turn compare the modern Iranian state to the expansionist Safavid (ṣafawī) Empire or even the pre-Islamic Zoroastrian (majūsī) Empires.

Persian poetry was born in the centuries following the arrival of Islam in the Iranian plateau, but Persian speakers generally consider its zenith to be the 13th and 14th centuries. Hafez, the bard of Shiraz, is especially beloved and regarded as the premier Persian poet. It is his dīvān that can be found in every home beside the Quran, and every Iranian has at least one — if not many — of his couplets memorized. Hafez’s modest mausoleum just outside of Shiraz is a national monument, packed with locals and tourists on weekends and holidays. Both secular and religious Iranians pray and reflect for long periods of time at his gravestone.

Hafez (meaning memorizer of the Quran), also known as Lisān ul-Ghāyb (Tongue of the Unseen) and Tarjomān al-Asrār (Translator of Secrets) lived in the shadow of Genghis Khān’s sacking of Baghdad, a traumatic event that shook the Muslim world just a half-century before his birth. His native Shiraz avoided bloodshed but bore witness to political instability as petty dynasties rose and fell, each change of power reminding him of life’s fragility. One episode — the removal of Hafez’s favorable patron by a brutal sultan who had little appreciation for the arts and a taste for the harsh application of Islamic law — was particularly traumatic. Hafez spent the following years penning odes of protest lamenting this turn of events, particularly the closure of his beloved winehouses and the banning of music. Hafez also had scathing criticism for insincere piety of all kinds and likewise viewed religious folks of all stripes as nothing more than different flavors of hypocrites. The usurper sultan was eventually blinded and replaced by his more favorable son, who reopened the winehouses and reinstated Hafez’s patronage. The fatalism, despair, and disdain for religious authority found in his poetry should be understood in the context of this history. This also helps us understand Hafez’s place in the hearts of modern Iranians, who find themselves in a similarly tumultuous moment in time.

Just over a century after Hafez, the Safavid dynasty was founded in 1501. The new dynasty managed the various small dynasties ruling Iran under one political dominion, while converting the previously Sunni population to Twelver Shiite Islam. The Safavids refashioned the Iranian identity into a Shiite one, contrasting it with the larger, mostly Sunni Muslim world and their rival Ottoman empire. Iranians tend to consider the early Safavids period the most recent peak of Iranian history, both for uniting Iranian territory and the cultural heritage the vast empire patronized. Many of Iran’s most significant sites, from Isfahan’s Naqsh-e Jahan Square to Mashhad’s Imam Reza Shrine were either built or significantly developed in this era.

After nearly three centuries, the Safavid Empire would succumb to an Afghan invasion from the east and be replaced by the Qajar dynasty after a 53-year interlude. Unable to keep up with the rapid emergence of modernity, the Qajar dynasty would quickly degenerate and lose territories in the Caucasus and Central Asia, shrinking the once vast empire to the modern boundaries of Iran. Persian poetry was largely a court tradition, and as the Qajar monarchs fell into greater debt, their funding for letters declined. In any case, many of the tropes, images and ideas of Persian poetry had become well worn by this time, and the genre was in dire need of renewal. Iranians generally consider the poetry of this era to be of inferior quality, as one poet told me, “A single couplet from Sa‘di (died circa 1292) is worth 10 Qajar dīvāns.”

By the early 1900s, Iranians were pressuring the Qajar monarchy to give United Kingdom-style concessions to the people: They wanted a Western-style constitution limiting the monarch’s power and guaranteeing rights in Western terms, a parliament, and other modern institutions. Iranian poets began writing revolutionary poetry, protesting oppression and dreaming of a new Iran. Though the poetry was still written according to classic conventions, the poems had an unmistakably modern subject matter. After a general known as Reza Pahlavi dethroned the Qajars in a coup d’état, any hopes for a freer Iran were crushed. Mohammad-Taqi Bahar (known as Malek ash-Sho‘arā’ “poet laureate” or “king of poets”) wrote the famous “Morgh-e Sahar” (Dawn Bird) in prison during the early 1920s. With his dreams of a constitutional Qajar monarchy crushed, he complained about Reza Shah Pahlavi’s oppression and yearned for freedom: “Dawn bird, refresh your lament! Make my pain burn even more … The landlord’s oppression, master’s tyranny, the farmer’s turned restless from his sadness.” (morgh-e sahar nāleh sar kon, dāgh-e marā tāzeh tar kon … zolm-e malek, jawr-e arbāb zāre‘ az ḡam gashteh bītāb). The poem became so famous that Reza Shah eventually banned it, but the poem remains among the most famous odes in Iran.

If the tradition of court poetry had declined in the Qajar era, it died an unceremonious death under Reza Shah, who was a village boy with little taste for elite culture. The new monarch was more concerned with re-shaping Iran as a modern nation. Inspired by Mustafa Kemal Pasha’s (known later as Atatürk) fleeting Turkish Republic, Reza Shah plunged Iran headfirst into modernity by destroying, severely restricting or replacing the institutions that were once cornerstones in Iranian society. For the first time, Iranian intellectuals began to travel and study in Europe in large numbers. Taking note from the free-verse poetry that had been prevalent in the West for nearly half a century, they began to experiment with a similar style in Persian. New poems were written without traditional stanzas and rhyme schemes, and the court imagery of balls, banquets and battles was mostly abandoned in favor of newer, more relevant themes like women’s rights, national identity, political representation, freedom and more.

After World War II, the British dethroned Reza Shah Pahlavi in favor of his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who would prove a less successful monarch. Early in his reign, the populist and nationalist prime minister Mohammad Mossadeq nationalized Iran’s oil, which led to the now infamous 1953 coup d’état. The young Mohammad Reza ultimately failed to hold his grip on the country, seeing many periods of instability that forced him to flee the country, earning him the title “Suitcase King” abroad. After just a few decades, the 2500-year-old monarchy was overthrown in a revolution and replaced with a new Islamic Republic in 1979.

Just as poets a half-century earlier had brought Iranian poetry into modernity, Iran’s political thinkers began to imagine a way to do the same with Iranian governance. Khomeini famously said, “Neither Western (secular, capitalist democracy) nor Eastern (communism) but an Islamic Republic.” As the newly formed republic attempted to forge a new, traditionalist Iran, it paid little attention to modernist, free-verse poetry. The government began to patronize traditionalist poets like Shahriar (Seyyed Mohammad Hossein Behjat Tabrizi), who revived Iran’s poetry with hundreds of newly composed odes written according to the conventions of traditional poetry. His language is unmistakably modern, but his poems are traditional in their spirit and form.

Shahriar helped revive Iran’s traditional poetry with hundreds of newly composed odes written according to classical conventions: “O needy beggar, go and knock on Ali’s door / for he’ll kindly give gems of kingship to the poor.” (boro ay gedāy-e meskīn, dar-e khāneh-yeh‘alī zan / keh negīn-e padeshāhī dehad az keram gedā rā). Though Shahriar’s language is unmistakably modern, his poems are traditional in their spirit and form.

Although no traditionalist poet on the scale of Shahriar has emerged since his death in 1988, the Iranian government continues to sponsor neotraditionalist letters. In the aforementioned poetry nights, poems recited to Khamenei are written according to traditional conventions, including the religious themes and symbolism of premodern poems with adaptations for our modern context. References to the wars in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen are common: “Peace be upon the legendary Irani / the living martyr Haj Qassem Soleimani … God is our witness, we’ve not run away to hide / we are still standing with Nasrallah by our side.”

And though the characters and sentiments may change – Persian poetry continues to live and breathe as it has for a millennium.

Note: ā corresponds to a long a sound, ī is a y sound, and ū is a long u sound.

The poems quoted in this piece are @sharghzadeh’s original translations.