Image-sharing websites like Instagram and Snapchat reveal a widely shared penchant for documenting the incidental moments of everyday life. When everyone has a camera on their phone, that documentation is easy. But in the 1930s, cameras were less common.

From 1931 until 1938, an archaeological team led by the American Schools of Oriental Research, a U.S.-based nonprofit, was working at Tepe Gawra and Tell Billa in northern Iraq. Apart from digging out Bronze Age pottery, beads and arrowheads, they also captured rare images of the Yazidis among whom they lived in the twin villages of Bashiqa and Bahzani on the Nineveh Plain.

Once the digs were completed, the archaeological data was documented and published in academic forums, but the almost 300 photographs of Yazidis disappeared into an archive at the University of Pennsylvania and were forgotten about. These were images of Yazidi life, society and celebration in Iraq, but few knew of their existence.

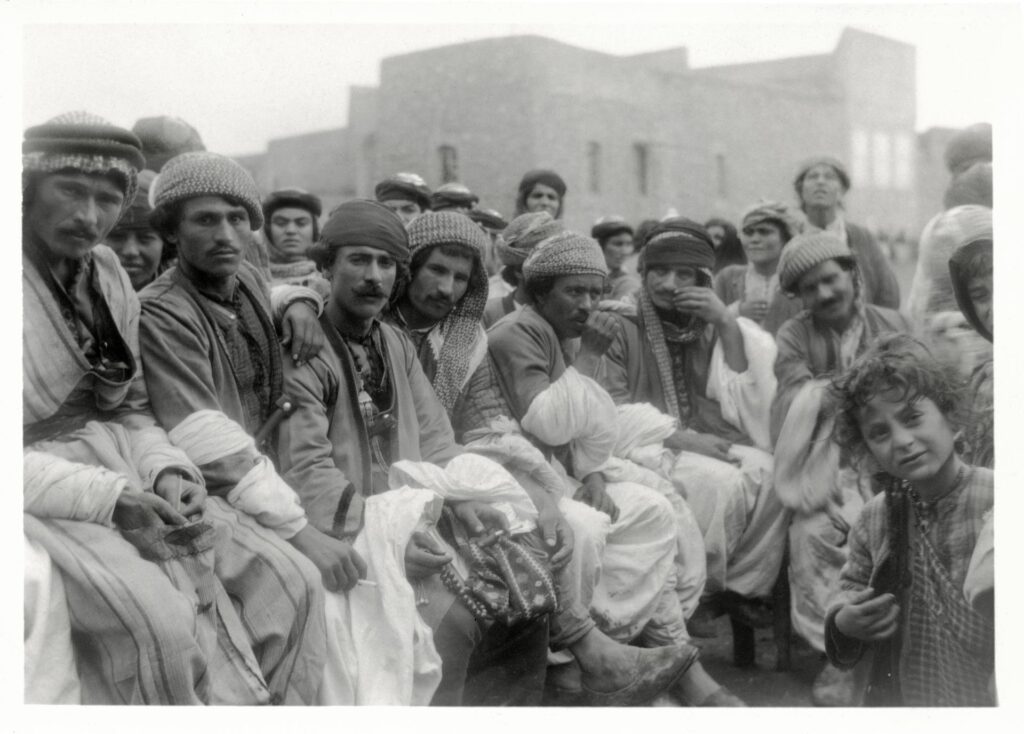

In 2022, Marc Marin Webb, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, happened across this cache of images. Conducting research on heritage preservation following the Islamic State group’s killing of Yazidis in 2014, he immediately realized the significance of the photographs. He made copies of some of the images on his mobile phone, and during his fieldwork in Bashiqa-Bahzani and Sinjar in northern Iraq he showed them to Yazidis. Marin Webb explained to New Lines that he wanted to corroborate the annotations of the photos in the archive, but he also found that they “helped to establish rapport with people in a region where distrust is very high.”

One of Marin Webb’s Yazidi contacts, who wished to remain anonymous for reasons of personal security, related that, after the Islamic State’s intentional destruction of Yazidi homes and their contents, finding, sharing and saving visual artefacts became all the more important. “Everyone was trying to collect photos from their grandfathers, old photos, family photos. … So, when Marc showed them [these] old photos, 90-year-old photos, they were really happy, and their faces [were] full of joy.”

The British cultural historian Peter Burke contended in his seminal work “Eyewitnessing” that images are mute witnesses, their testimonies difficult to discern. Yet Marin Webb found the photographs that he shared with Yazidis in Bashiqa-Bahzani spoke volumes. They opened a window into an earlier era, and became a thread that linked families and communities, consolidating a sense of identity and solidarity and bringing joy to a population that has endured disruption and trauma.

“I interviewed a local historian in Bashiqa,” Marin Webb explained, “and he recognized a person in one of the photographs. He said, ‘This is Bashir Sadiq. He was the son of the mukhtar [village head].’” During the time of the dig, Sadiq had acted as the archaeologists’ local “fixer,” and, Marin Webb was told, had learned to develop photographs and drive a car by watching “the Americans.”

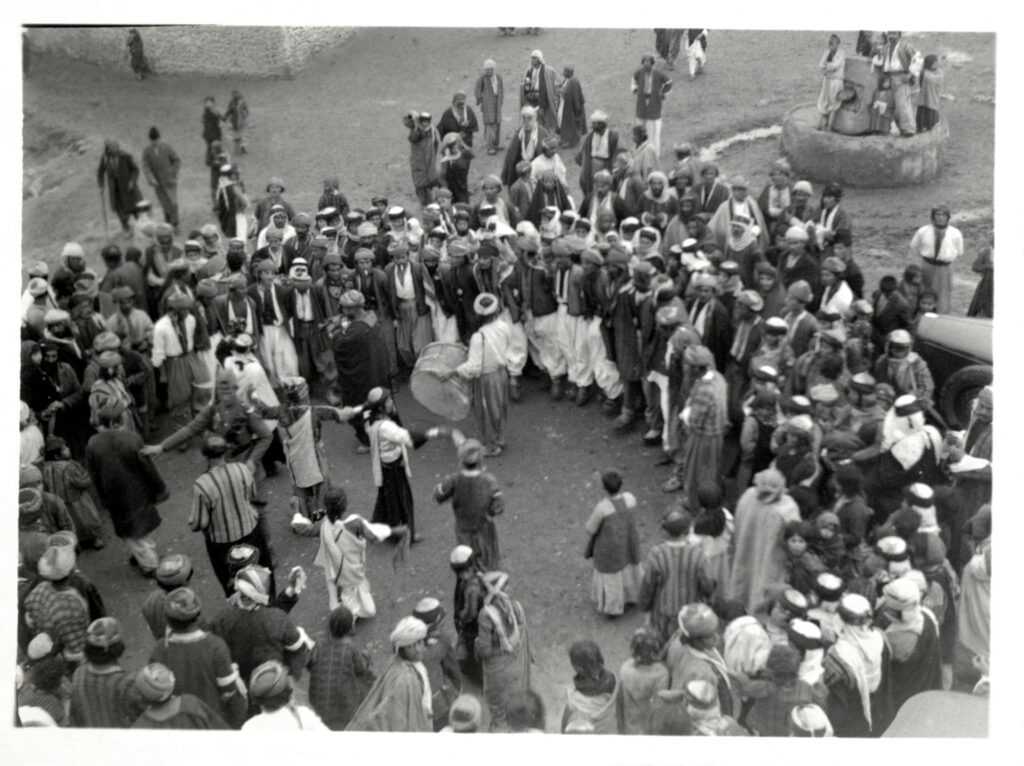

With this connection established, Marin Webb was duly whisked to the house of Sadiq’s family, who, having fled to Germany in 2009, had recently returned to celebrate Sersal, the Yazidi new year. As coffee was served, he showed the family photographs of the marriage, almost a century ago, of Sadiq to Naama Sulayman, as well as the bridal procession, performing musicians and assembled guests dancing the “dilan.”

This was not an unusual experience for Marin Webb. He noted that on repeat trips to northern Iraq, Yazidis always treated him to spontaneous hospitality. Showing copies of the archival images on his phone was, in a sense, recompense for the generosity he received, and it led to a wider conversation. “Everyone was insisting that they wanted copies,” Marin Webb recounted. “I had PDFs that I was sending to people. They liked that, but it’s not the same as having physical copies.”

Staff at the Near East collections at the Penn Museum had started the process of restoring and digitizing the images, but a larger project also began taking shape. Marin Webb shared the images with University of Victoria postdoctoral fellow Nathaniel Brunt, whose work focuses on preserving and making accessible visual materials in conflict and postconflict zones. In northern Iraq, this involves gathering nontraditional archival material, from family photographs and oral histories to mobile phone images and videos.

Marin Webb and Brunt then collaborated with Yazidis and others, from Iraq and the diaspora, to establish the Sersal Project, named after the Yazidi new year. This collective endeavor was initiated to “return” the archival images to Yazidi communities, some of whom, it was clear, were descendants of the subjects of the original photographs.

From the outset, Marin Webb and Brunt were determined to bring the images to as wide an audience as possible. Brunt explained that the first stage of the project involved exhibiting photographs in Bashiqa-Bahzani and Sinjar. “We did these in the street, in nontraditional spaces. We wanted to make sure people who would not normally go to a gallery could see the pictures.”

These events coincided with the Yazidi new year in April this year, when members of the diaspora return from far and wide. With such an audience, the images developed a momentum of their own. All images were posted with a QR code that pinpointed where they were being downloaded from. Brunt recalled tracking downloads as they rippled outward from northern Iraq, to Europe, the U.S., Canada and Australia, with images later reappearing in social media posts. As he noted, “The exhibition is now permanently located in Khanasor, but it also has this digital afterlife.”

The project also participated in the Erbil International Book Fair this year, supported by the Goethe-Institut Iraq, exhibiting high-resolution versions of the 1930s photographs and hosting a performance of the Mirzo Music Foundation, a well-loved Yazidi musical group, who had composed songs specifically to accompany the event. Marin Webb notes that Mirzo is well known across Iraq and the event attracted a wide audience that was generally unfamiliar with Yazidi music, culture and history.

The Yazidis remain a little-known people. Anthropologist Christine Allison writes that outsider accounts tend to be “sensationalist, ill-informed or worse,” some casting the Yazidis as exotic or mysterious, and others perpetuating untruths about their faith and rituals. In Iraq, they are sometimes the subjects of rumor and slander based on these untruths, and, particularly amid the turmoil that arose after the 2003 U.S. invasion, they have been targets of abuse and violence. They were virtually unheard of among the Western public until the horrors visited upon them by the Islamic State in 2014.

The first record of the Yazidis as a distinct community appeared in the “Sharafnameh,” a Kurdish historical genealogy, published in 1597. Michel Febvre, a Capuchin monk who traveled through Ottoman territories in the 1680s, was the first to bring them to the attention of Europe. Yet reliable information remained scant. An East India Company official in Baghdad in the 1820s claimed that Yazidis routinely lived to 100 years old in their mountain fastnesses, women continuing to bear children until 60, while also being custodians of a treasure trove secreted in a well inside a cave.

The origins of Yazidism, a monotheistic, orally transmitted religion with its own Holy Trinity and scriptures, are shrouded in the distant past. Yazidis believe their faith to be one of the oldest in Mesopotamia. In her detailed 2010 study, “The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion,” the historian Birgül Açıkyıldız notes that the faith was once practiced across an expansive territory, from Lake Van in what is now Turkey, to Suleymaniye near the Iran-Iraq border, to Antioch on the Mediterranean coast, as well as the Sinjar and Sheikhan regions of northern Iraq, which remain the strongholds of the Yazidis. This domain effectively coincided with the territory in which Kurds reside. During the 14th and 15th centuries, major Kurdish tribes and leaders such as the emirs of the semiautonomous Jazira territory practiced Yazidism. At this time, as historian John Guest documents, Islamic thinkers wrote favorable commentaries on the writings of Sheikh Adi, a central figure revered by Yazidis.

This realm was one of considerable ethnic and religious diversity. Guest notes in “Survival Among the Kurds” that Yazidis lived amicably among Assyrian and Armenian communities, some of them teaching their children to speak Turkish and Armenian alongside their mother tongue, Kurmanji. But Yazidism reached a high tide mark in the 15th century. Açıkyıldız contends that perhaps because their influence and political weight were growing, they were perceived as a threat by local Arab, Persian and Ottoman rulers, many of whom, over centuries, “organised pogroms against the Yezidis.” These injunctions were generally cast in religious terms, justified by misunderstandings, or deliberate mischaracterizations, of the Yazidi faith.

Austen Henry Layard, the famed English archaeologist who unearthed the ancient Assyrian cities of Nimrud and Nineveh in the 1840s, observed at firsthand religious prejudice aimed at the Yazidis. He once encountered a sheikh, “notorious for his hatred of Yezidis … one of those religious fanatics who are the curse of Kurdistan.” Meanwhile, the missionary William Ainger Wigram, en route to Mosul in the early 20th century, wrote in “The Cradle of Mankind: Life in Eastern Kurdistan” that a Yazidi followed his entourage, but at a discrete distance. A “zaptiye” (local guard) accompanying him signaled violent intent toward the Yazidi but told Wigram he refrained from acting due to his presence.

Such bigotry often did spill over into violence. Yazidi history is littered with tales of massacres. The ransacking in 1415 of the tomb of Sheikh Adi at Lalish, the holiest site for Yazidis, was one of the earliest such events. The political realignments and power struggles of the latter years of the Ottoman Empire were also traumatic. Yazidis recall that Kurdish emirs Bedir Khan and Muhammad Pasha of Rawanduz repeatedly sent their cavalry against them during the 1830s, while in 1890, the Ottoman commander Omar Wahbi Pasha of Mosul delivered the Yazidis an ultimatum to convert to Islam or face military retribution. Many Yazidis refused, and, in response, he massacred the inhabitants of Sheikhan and Sinjar. The following year, many Yazidis were targeted by the Hamidiye cavalry brigades as Sultan Abdulhamid II sought to subdue ethnic and religious minorities and prevent the fragmentation of the empire.

These episodes loom large in the Yazidi imagination. They refer to them as “fermans,” after the Ottoman word for “edict,” which they have come to construe as “genocide.” It is commonly held by Yazidis that throughout their history they have been victims of 74 fermans. Accordingly, they regard persecution — and enduring in the face of it — as a central pillar of their identity. The violent attacks of the Islamic State in 2014 were the last of those genocides, and followed a similar edict delivered by the purported new caliph.

In contrast, the photographs in the University of Pennsylvania show a period of relative calm. Administered by the British under mandatory powers from 1921, Iraq became independent in 1932. Faisal al Hashimi, newly appointed as Iraq’s first king, made guarantees that ethnic and religious minorities would be protected, declaring, “Protection of life and liberty will be assured to all inhabitants of Iraq without distinction of birth, nationality, language, race or religion.” One of his goals was to forge a national identity that could accommodate the diverse religious and ethnic communities that lived within Iraqi territory. The wedding processions, communal dances and snapshots of village life in the photographic archive show Yazidis going about their lives in this political milieu, when optimism reigned and tensions were in abeyance.

The Sersal Project, with Marin Webb and Brunt at the helm, is thus a valuable artefact of that particular era. But it also has wider implications for the Yazidis themselves and Iraqis as a whole. Significantly, it portrays Yazidis in circumstances other than being victims of persecution and violence. Marin Webb recalled that one Yazidi, who helped during the installation of the exhibition in Bashiqa, remarked, “Thanks for bringing the photos and showing to the world that we had lives before the genocide.” Brunt, with a track record of documenting postconflict situations, also remarked on the overwhelmingly positive response the “joyful photos” of the exhibitions received.

Nadia Murad, who escaped slavery under the Islamic State and won the Nobel Peace Prize, recently lamented that genocide “reduces human beings to lists and numbers.” The Sersal Project works against this: It puts human faces on the Yazidis. Marin Webb explained that the exhibition raises awareness of the precarious plight of the Yazidis, but also of their cause and their identity: One of his Yazidi contacts celebrated that the photographs “show who we are.”

This, in turn, plays a part in a wider embracing of Yazidi traditions and identity among the younger generations. As has happened the world over, the fast pace of modern life, rife with trends, fashions and fads, saw young Yazidis distancing themselves from their folklore, music and history. Marin Webb’s Yazidi contact told me that hate campaigns against Yazidis during the upheavals in Iraq after the U.S. invasion accelerated this, prompting some to conceal their identity and heritage. But he noted that the tide has turned since 2014, and there is now a growing appreciation for traditions and the patterns of life as it used to be. It is not just older generations who have enjoyed seeing photographs of their forebears — Yazidi youth have also flocked to the exhibitions, recognizing that they are testimony and affirmation of their traditions, culture and presence in Iraq’s sociopolitical landscape.

Brunt observed that another motivation for bringing the exhibition to Erbil was to display the images to an audience that extended beyond Yazidis, and that the wider Iraqi population — Sunnis, Kurds, Christians — should see Yazidis in situations other than trauma. “The photographs,” Brunt remarked, “show these people as … multidimensional… and not just victims of genocide.” Family photographs — of weddings, dances, village life — are a perfect mechanism for doing so, and are also immediately relatable for those without a Yazidi background.

Ultimately, these photographs are testament to the resilience of the Yazidis. As Guest notes, the Yazidis have endured in a rugged landscape through torrid periods of history, outlasting the Mongol invasions, the Black Death and the Timurid Empire. The horrors perpetrated by the Islamic State were another of these episodes, the traumas still lingering for many.

The Yazidi source told me of his people’s defiance. The archival photographs and the exhibitions they have spawned are “a message to the ISIS and the people who want to destroy our culture and our religion.” They are, he declared, a message that “we are still here, and we are fighting, and we will keep fighting.”

So, while the central characters of the archival images — Bashir Sadiq and his bride and the wedding musicians — may no longer be here, the pictures, now available to the Yazidi community and beyond, keep these “joyful” moments alive. And, in their ability to fortify the identity of a persecuted people and to humanize that persecuted people to the wider population, they remain an inexhaustible resource.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.