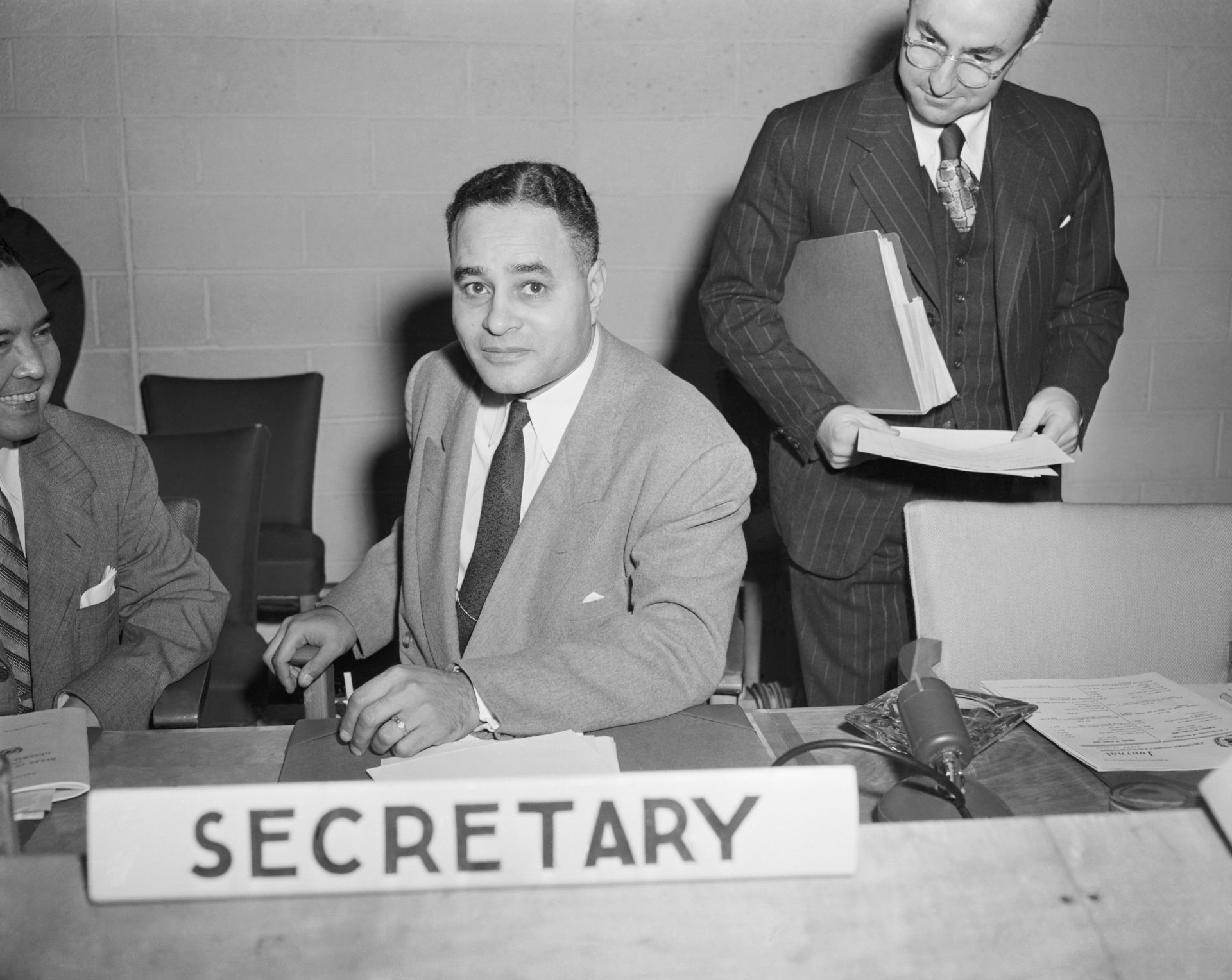

The following is an adapted excerpt from Kal Raustiala’s recently published book “The Absolutely Indispensable Man: Ralph Bunche, the United Nations, and the Fight to End Empire.”

On March 29, 1951, at the Pantages Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard, hundreds of actors, directors and entertainment moguls gathered for the 23rd Academy Awards. The crowd — and the many listeners on the radio nationwide — waited for the final and biggest award of the night: best picture. Among the films in the running were the Spencer Tracy comedy “Father of the Bride”; “Sunset Boulevard,” the classic saga of old Hollywood decline; and “All About Eve,” the Broadway drama starring Bette Davis.

As the excitement built, the host for the evening, the dapper, slim Fred Astaire, leaned into the podium. “For the presenter of the final award,” Astaire said,

We’ve stepped outside the industry. We’ve stayed true to our Los Angeles roots, however. I’d call him the town’s most distinguished son. He achieved the miracle of peace in Palestine; he won the Nobel Prize; he is now one of the large figures in the United Nations organization. It’s an honor for all of us to hear from Dr. Ralph Bunche.

Ralph Johnson Bunche, a 46-year-old official at the new United Nations, walked across the broad stage wearing a white tie and tails and clutching some papers. Abundant applause and a fanfare of trumpets rang out. Bunche, who had grown up in Los Angeles, paused at the lectern to look out at the sparkling crowd. Speaking at first a bit stiffly and slowly, he thanked Astaire and began his speech.

Quickly striking a serious tone and invoking the Cold War context of 1950s America, Bunche declared that it is “imperative to our way of life that this great medium be kept fully free.” Freedom, he continued, brought “sober responsibilities.” As a result, it was vital that the American film industry reflect democracy and “be directed toward democratic objectives.” As the audience listened respectfully, he discussed the new United Nations organization, which just five years before had held its first meetings in London. The Cold War had already shattered many hopes about peace and cooperation in the postwar world; the Korean War was well underway as Hollywood’s glittering stars and powerful moguls listened to Bunche’s remarks. That very morning, in a courtroom in New York, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg had been convicted of spying for the Soviet Union and would soon be sentenced to death.

Despite this chilling global context, Bunche remained optimistic. The U.N. looked to Hollywood, he explained, for aid in achieving a world of peace and brotherhood. Bunche (or perhaps his speechwriter) tried to leaven this sober message with a few weak jokes about comedy and drama among diplomats. But he soon returned to the main point he wanted the audience to take home: through the U.N., “honorable peace can be achieved and secured.”

His address complete, Bunche turned to the pressing matter at hand: the winner of the Oscar for best picture. After being handed a small white card — envelopes were not yet used in those days — he brought the heady evening to a close, announcing that “All About Eve” had triumphed. As legendary producer Darryl Zanuck bounded up to the podium, Bunche smiled broadly. Bunche offered Zanuck a golden statuette and shook his hand.

Ralph Bunche’s turn on the Academy Awards stage was emblematic of the extraordinary celebrity he enjoyed in midcentury America. His fame was not just recognized by Hollywood. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he was bombarded with speaking invitations, job offers and appeals for his appearance. His Nobel Peace Prize, awarded the year before he spoke at the Pantages Theatre, recognized his groundbreaking mediation between the new state of Israel and its Arab neighbors. The Nobel made Ralph Bunche a household name for many Americans. He received a ticker-tape parade down Broadway’s Canyon of Heroes and became the subject of an inspirational ABC docudrama. Presidents sought his advice; world leaders his attention; visionaries and activists — including Martin Luther King Jr. — his advocacy. Bunche had enjoyed abundant professional success but relatively little personal fame until his landmark efforts in Palestine brought him to popular attention.

The mediation in the Middle East changed his life. He was soon on a first-name basis with presidents from Harry Truman to Richard Nixon. His impressive and inspirational life story became grist for the mill of American progress. The Nation called Bunche “a symbol throughout the world of the American Negro’s increasingly effective struggle for equality.” The New Yorker described his life as “exhilarating” and “marvelously bound up in the fabric of everything we love about this country.”

As a high-ranking Black man in the very white world of diplomacy, numerous administrations sought to bring him back to Washington, D.C., from the U.N., where he remained until his untimely death in 1971. Once “the most honored African American in America,” Ralph Bunche is largely forgotten today. He is remembered by some as a master of international diplomacy, by others as an icon of racial equality. Yet he is little known to the public at large.

Bunche merits renewed recognition both for his extraordinary American life and for the lens he provides on two significant features of the 20th century — the creation of the postwar international order and the struggle for racial equality — that are rarely joined but deserve to be and that he himself married in the realm of ideas and in his own person. As a scholar, he helped produce the landmark book “An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy.” As an advocate, he marched arm in arm with King from Selma to Montgomery. Yet he spent most of his career as a diplomat at the United Nations. His hands lay behind some of the signal features of the postwar order, from peacekeeping to conflict mediation to his most significant and lasting legacy, the one that made both peacekeeping and mediation so often necessary: the dismantling of European empire.

Bunche saw no dissonance in this pairing of diplomacy and civil rights. He fought to make both America and the world more just, more free and more fair. During his lifetime — and in part because of his efforts — nearly a billion people of color gained independence from foreign rule.

Independence Day in Congo dawned on June 30, 1960. The ceremonies in Leopoldville began that day and continued on July 1, with a “Fete de l’Independence” ironically held in Stade Roi Baudoin — King Baudouin Stadium — an arresting emblem of how entangled the new state of Congo and the old state of Belgium continued to be. The young Belgian monarch had flown in for the occasion, arguably a misreading of the political situation on the ground. On the drive in from the airport, riding in a slow-moving open Lincoln Continental, the king’s ceremonial sword was snatched by a souvenir-hunter (neatly dressed in a dark jacket and tie) who, in a moment of triumph, clutched it above his head in celebration. It was a sign, perhaps, that the situation in Congo was teetering on the edge of shambolic, and a potent symbol of the shifting political order in Africa. “Very symbolic! Like he was snatching the king’s power,” noted one observer who many years later became the foreign minister of Congo. Armed police soon surrounded the interloper as the spectators lining the broad tropical avenue looked on in amazement.

Watching the independence parade that day, Bunche was troubled. Congolese troops marched down Leopoldville’s broad tropical avenues in formation, and fighter jets flew overhead. But the troops were led by Belgian officers, white men. At previous independence celebrations, such as that of Ghana in 1957, national troops were commanded by national officers drawn from the local populace. Here, the former colonial power seemed to be hedging and not quite taking its hands off the steering wheel. Bunche no doubt thought of his meetings in Brussels the week before. Turning to his aide, he said, “Something is wrong.”

The formal independence ceremonies began in the grand circular hall of the National Palace. Built to be the residence of the Belgian governor-general, the palace was a colonnaded, modern building situated on the grassy banks of the Congo River facing French Brazzaville on the other side. The room was filled with members of the new Congolese government, Belgian officials and foreign dignitaries like Prince Hassan of Morocco and King Kigeri of Rwanda. Participants had come from all over the world; even tiny Israel sent a delegation. Most in attendance, including the new Congolese leaders, wore dark Western suits and ties, but here and there traditional African headdresses with seashells, feathers and animal skins could be spotted.

Bemedaled and wearing a striking white military uniform, King Baudouin addressed the dignitaries and new Congolese leadership gathered in the Chamber of Deputies. Standing at a microphone and holding his notes in his hands, the king fully channeled the prewar creed of the White Man’s Burden. Baudouin’s tone-deaf and bombastic speech stressed the importance of Belgium’s role in the history and development of Congo. He even praised the “genius” of his great-great-uncle, King Leopold II, who for decades had ruled Congo and presided over some of the most horrific atrocities ever perpetrated in Africa. As if to underscore his hauteur, he declaimed that “it is up to you, gentlemen, to demonstrate that we were right to have confidence in you.” Baudouin’s remarks were punctuated with ceremonial gunfire. Bunche, writing later, called Baudouin’s speech a “grave error.”

The new president of Congo, Joseph Kasavubu, followed the king in the chamber but offered only a mild and diplomatic, even obsequious, response. Then the African nationalist leader and eventual prime minister Patrice Lumumba, who was sitting next to Belgian Premier Gaston Eyskens, stood to speak. Lumumba was a late addition; he had not originally been scheduled to speak at this ceremony. Footage of the event shows Lumumba furiously scribbling as Baudouin spoke, perhaps revising his remarks on the fly. Malcolm X would later call it the “greatest speech” by the “greatest black man who ever walked the African continent.”

Speaking in French and wearing a dark suit, narrow bow tie and maroon sash — signifying Belgium’s highest honor, the Order of the Crown, which he had just received the night before — Lumumba began by welcoming the “victorious independence fighters.” He then proclaimed the “glorious history of our struggle for liberty.” That struggle, he said, had put an end to the “humiliating slavery that had been imposed on us by force.” Lumumba spoke in a calm voice and cadence, but his words were sharp and uncompromising, and they rapidly deflated the false bonhomie of the event. He reminded the assembled Congolese of

[t]he ironies, the insults, the blows that we had to submit to morning, noon and night because we were Negroes . . .

We have seen our lands seized in the name of allegedly legal laws which in fact recognized only that might is right.

We have seen that the law was not the same for a white and for a black, accommodating for the first, cruel and inhuman for the other.

We have witnessed atrocious sufferings of those condemned for their political opinions or religious beliefs, exiled in their own country, their fate truly worse than death itself . . .

All that, my brothers, we have endured.

Then, in an arresting phrase, very likely apocryphal but oft-quoted, Lumumba declared to the king and the other Belgian leaders in the room, “As from today, we are no longer your monkeys.”

Lumumba’s electrifying speech upended the ceremonies. Congolese gave him a standing ovation. Belgian leaders “had tears in their eyes” in the aftermath. The proceeding paused for an hour while the king, whose veins on his forehead had “stood out as an indication of the violence of his feelings” during the speech, threatened to leave. The Guardian called the speech “pugnacious” and “offensive.” The New York Times reported that Lumumba’s speech “produced comments of surprise and disappointment among Belgian and other Western representatives.” The Soviet diplomats present, however, “seemed to be enjoying the occasion.” In six months Lumumba, who to many Congolese was now the face of resistance to Belgian domination, would be dead.

Reporting back to U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold, Bunche was a bit unnerved. He told him that “the operation of handing over powers here was quite ragged.” The independence ceremony became a crisis “and nearly a disaster” because of Lumumba’s “acid, hard-hitting anti-colonial speech.” But he placed his finger on the cause: “The King’s speech, which was the first, boasting of Belgian contributions . . . was maladroit and ill-advised to say the least.” Leopold’s rapacious rule was one of unremitting horror for many Congolese, and the paternalistic rule by the Belgian government that followed, while improved, was hardly much better. Lumumba, Bunche told the secretary-general, could not resist the provocation; the opportunity was too great to attack the king and “make big political capital by lambasting the departing masters” while also “implicitly whacking” his rival, Kasavubu.

Bunche, an experienced diplomat, seemed a bit startled by Lumumba’s blunt and intense address in such an august and formal setting. Unlike most of the foreign press covering the event, however, he understood that the real misstep had been Baudouin’s. Still, even some in Congo were unnerved by the remarks. One political ally of Lumumba’s said: “I was in the audience and I was struck dumb. Lumumba acted like a demagogue . . . he’s committing political suicide, I thought.” Recounting the events to Hammarskjold in copious detail, Bunche described being in a car soon after the event with the Congolese diplomat Thomas Kanza. The vehicle was attacked by a group of political opponents, including a “burly, half-drunk rogue” who began to beat on the car. “It was Kanza’s car, but I ordered the driver to get away quickly,” he wrote. “These people take their politics . . . very emotionally.” (Coming from Bunche, this was not a compliment.) He then made an important prediction: Unless there is strong leadership and strong government, “there can be a disintegration approaching calamity.”

Bunche’s unease about the handover of power was prophetic. The entire Independence Day affair was an augury of what was to come. A couple of days later, at a sporting event meant to mark the celebration, Lumumba snatched the trophy from Kasavubu and awarded it to the winners. Then, in less than a week, the real chaos began.

The first steps involved the army. Congolese soldiers in the Force Publique mutinied against their white Belgian officers. The Belgian commander, Lt. Gen. Emile Janssens, had written on a blackboard at a large meeting of officers, “Before Independence = After Independence.” Often pointed to as a key spark of the mutiny, Janssens’s open acknowledgment of Belgium’s intentions simply slipped the mask off of elite attitudes toward postcolonial Congo. Soon the military uprising, which easily overpowered the few Belgian officers left, spread throughout the country. Europeans, who were already on edge, began to flee.

Disorder ensued quickly in part because so much of it had been anticipated. Eleanor Roosevelt was not the only one who feared Congo was not ready to assume self-rule. Just days before the independence ceremonies, one of Bunche’s U.N. colleagues argued that “even if all goes well” the system in Congo would be highly lopsided. Unless the Belgians continue to play a major role, he predicted, “there may be prolonged chaos.” In the weeks before Independence Day, news outlets also portrayed rising racial anxiety among Europeans. Reports in the West often seemed to stoke fears as much as describe them. Tension is rising to “near-panic” among whites, the Associated Press reported, in the wake of “anti-white threats” in local newspapers. A chief concern, the AP claimed, “is for the white women. African propagandists are boasting they will be ‘ours’ after independence.” The newspaper of one native nationalist movement said that soon “it would no longer be a crime for Africans to rape white women.”

These and other alarmist stories spread substantial fear in the West of what was to come. One reporter suggested that only deft political maneuvering could save the situation: “A broadly based coalition government wide enough to include extreme Congolese nationalists is being urged as the sole hope of saving the Belgian Congo from anarchy and revolution when this enormous colony achieves independence June 30.” This particular story was prescient about other events as well: “’Lumumba will be premier or he will be assassinated or will become a terrorist,” gloomily predicted one observer.

As disorder spread rapidly in the wake of the July 5 mutiny, many European residents were terrified. Belgian men even disguised themselves as women to get priority on transportation out of the country. Foreign delegations in the country, also fearful of the repercussions of rising violence, quickly appealed to the Belgians to restore calm. In response, armed Belgian soldiers were dispatched, ostensibly to protect their citizens, but without the approval of the now sovereign Congolese government.

This was a critical turning point in the crisis and a violation of the new nation’s sovereignty. Rather than a celebration of African liberation, Congo’s independence was quickly becoming a demonstration of continuing European power and control. The Force Publique was seemingly ungoverned, Europeans were bolting across the Congo River to the French colonial city of Brazzaville in panic, and Belgian troops were rolling in. Order was breaking down.

Bunche was in his Leopoldville hotel on July 8 when he saw vehicles outside filled with Congolese soldiers brandishing weapons and shouting. No one seemed to be in control. Eyeing the scene from his balcony, he saw the troops point their guns at the ambassador from Israel. Soon, gun-toting soldiers were banging at his door, ordering him downstairs. He quickly hid some confidential documents behind the toilet and followed them to the lobby, where other guests, ordered to remain in place, cowered as the soldiers milled about. Eventually, the armed men left.

Bunche would later tell reporters that a “mutinous army” had gained control of Leopoldville. There was, he said, nothing to oppose it. “The city was completely at their mercy. They were strongly armed and they came into buildings, hotels, houses and apartment houses, and I am frank to say that I have never been so frightened in my life as I was at that time.” From this point forward, he would remain in nearly constant contact with Dag Hammarskjold as the two attempted to chart a path out of the careening chaos.

Bunche also wrote to his son, Ralph Jr., later that day:

Dear Ralph,

The way things have been here all day today and are going tonight, I cannot be sure when I can mail this letter to you. In truth, I cannot be positive at this moment if I ever will be able to mail it. For there are some heavily armed Congolese soldiers down in the lobby right now ordering people around pretty roughly at gun point. It is touch and go when one of them may erupt and start banging away with one of those automatic rifles they carry . . .

It is quite dangerous to go out in the daytime and forbidden to go out at all after 6 p.m. The streets are completely deserted now and this is like a dead city.

I have five people with me — four men and a woman — and they all hold up extremely well under this strain. You can never be sure what is happening when a shot is heard, or a knock on the door or the telephone rings. . . . One couldn’t run away if one wanted to, as there are no planes operating. But you can’t run away from duty in any case.

Well, if things work out all right in the end this predicament we are all in now will later seem quite amusing. Wouldn’t it be ironic, though, if I should now get knocked around here in the very heart of Africa because of anti-white feeling — the reason being that I am not dark enough and might be mistaken for a “blanc”! Well, life is full of ironies.

Following Bunche’s death in 1971, tributes and assessments poured forth from politicians, diplomats and newspapers around the world. In its obituary, the New York Times wrote that Ralph Bunche

could haggle, bicker, hairsplit, and browbeat, if necessary, and occasionally it was. But the art of his compromise lay in his seemingly boundless energy and the order and timing of his moves. His diplomatic skills — a masterwork in the practical application of psychology — became legendary at the United Nations . . . as such, he was [the] highest American figure in the world organization and, incidentally, the most prominent black man of his era whose stature did not derive chiefly from racial militance or endeavors specifically on behalf of his race.

In an editorial, the Times called him the “personification of the United Nations.” The Los Angeles Times, in a tribute to one of the city’s most prominent sons, described him as simultaneously a symbol of Black achievement and a reminder of “the unfinished business of equality.” Above all, the newspaper wrote, Ralph Bunche “demonstrated and elevated the dignity of man.”

His funeral, on a windy, bright, sunny winter day, was held at the Riverside Church on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. George H. W. Bush, Henry Kissinger, head of the NAACP Roy Wilkins, New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, New York City Mayor John Lindsay and a congeries of other politicians, diplomats and friends were in attendance. In a nod to his long-standing love of music, Leontyne Price sang a cappella. In his eulogy, U.N. Secretary-General U Thant called his long-time aide and consigliere a “practical optimist” whose life was devoted to the endless quest for peace.

These paeans were expected for a man who had held enormous stature in American, indeed global, life for over two decades. None of the major obituaries, however, noted that just a year before his death, the General Assembly had promulgated what would later be seen as a milestone in the evolution of the organization. In the fall of 1970, at the 25th anniversary session, it passed the Declaration on Friendly Relations and Cooperation. The declaration called out colonial rule as a violation of the foundational premises of the U.N. Charter. Specifically, it decried “the subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation,” opposed foreign intervention in the domestic affairs of independent states and pronounced that the principles of equal rights and self-determination of peoples constituted a significant contribution to international law.

The resolution, passed without any dissenting vote, was largely the product of the many new members of the U.N. who had recently escaped colonial rule. From an original 50 member states, the organization had nearly tripled in size by December 1971, straining the capacity of the campus built on the East River of New York. The presence of these numerous new and independent states at the United Nations, more than any of the eloquent expressions of admiration and respect from presidents and prime ministers pouring in from around the world, was perhaps the finest testament to the life and work of Ralph Johnson Bunche.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.