The liberal-democratic world is flagging. Vladimir Putin’s aggression against Ukraine represents a direct assault not just on a sovereign democratic state but on democratic norms and values more broadly, and it is inspiring authoritarian-nationalist despots and demagogues elsewhere, while illiberal tendencies are growing even within democracies.

In the United States, Donald Trump and his MAGA movement, having illegally attempted to overturn his 2020 presidential election defeat, are agitating for the abandonment of Ukraine to Putin. Trump is overwhelmingly likely to be the Republican candidate for the 2024 presidential election, which he may even win. In Europe, Germany and France drag their feet in supporting Ukraine and the far right is rising in both countries, while France imposes discriminatory new restrictions on the attire of its Muslim citizens. Britain, weakened and disoriented by Brexit, has been pursuing a policy to send asylum-seekers to Rwanda, ruled by the repressive autocrat Paul Kagame. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan have undermined the liberal-democratic camp by obstructing Finland and Sweden’s entry into NATO. Thanks to them, Sweden, which applied to join in May 2022, is still not a member. Turkey, which 20 years ago seemed a beacon of democratization in the Muslim Middle East, is today one of the world’s worst jailers of journalists. In Israel, the government of Benjamin Netanyahu is attempting to neuter the country’s supreme court while escalating its oppression of Palestinians.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine may constitute the biggest assault on the liberal-democratic world in Europe since the end of the Cold War, but it is far from unprecedented. It had a precursor in Serbia’s attacks on Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo in the 1990s, and in Croatia’s own collusion in Serbia’s assault on Bosnia. This is widely forgotten by Western journalists and pundits who comment on the war in Ukraine: The Balkans have, for generations, been dismissed as improperly European, an unstable, atavistic borderland with Asia that serves only to distract from the supposed European norm.

This Western mental blank about the 1990s Balkan wars is unfortunate, insofar as the latter provide lessons relevant to the problems facing Europe today. The rise of authoritarian nationalism in Serbia and Croatia marked these countries out, not as aberrations in Europe, but as quintessentially European, suffering from a malaise that would afflict other European countries. And just as Serbia and Croatia were early sufferers, so they produced early seekers of a cure: dissident intellectuals who attempted to tackle the authoritarian-nationalist virus and who have something to teach liberal democrats today in the rest of the continent and beyond.

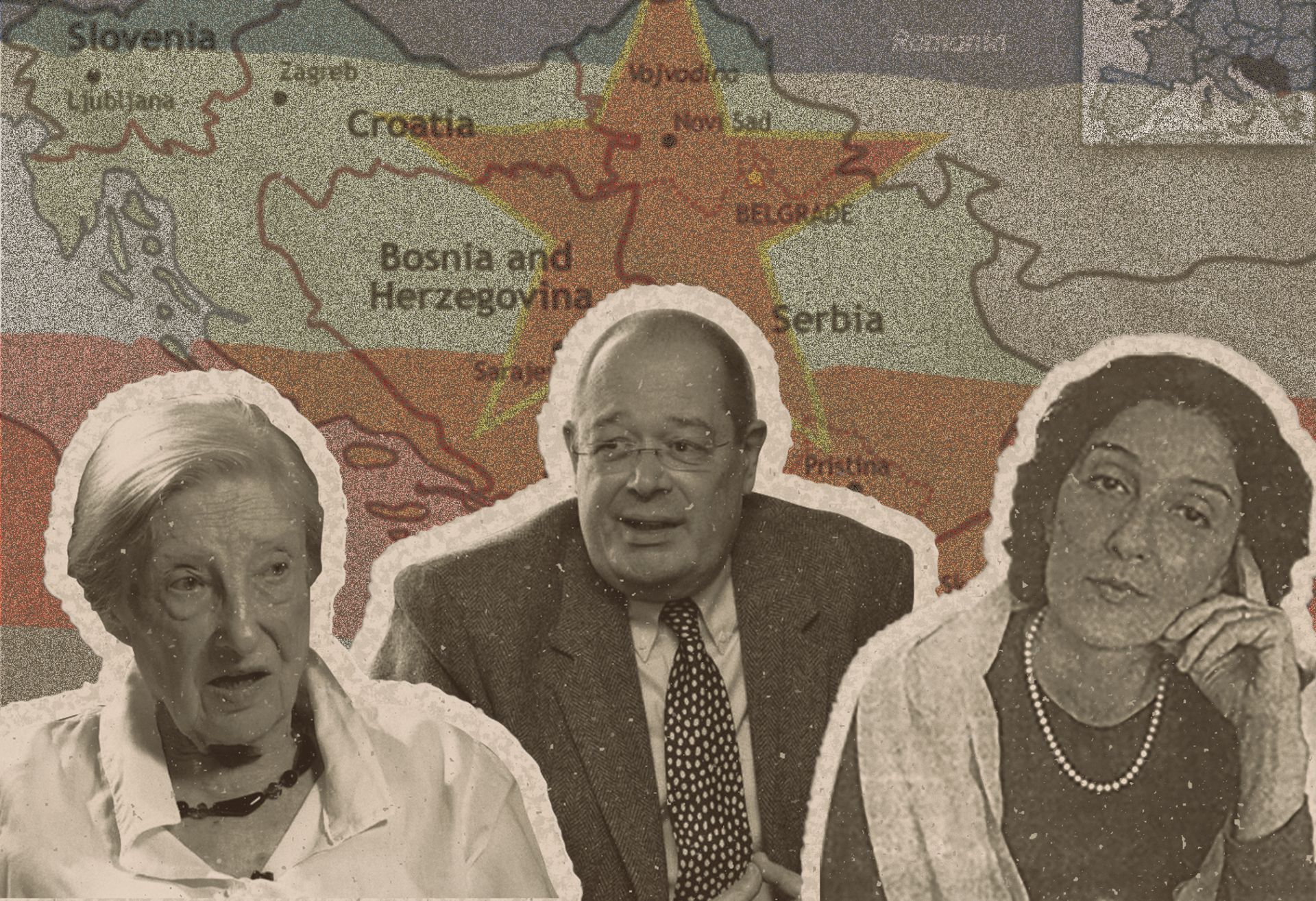

“The historian is a prophet looking backward,” said the German Romantic poet and philosopher Friedrich von Schlegel. For Serbia’s Latinka Perovic, who died in December 2022 at the age of 89, her lifelong quest to understand her country’s past was closely linked with her wish for it to avoid repeating its mistakes and achieve a happier future.

Perovic was widely considered the “mother of the Other Serbia.” The “Other Serbia,” or “Second Serbia,” was an intellectual and political current that arose in the early 1990s in opposition to the nationalist and warmongering policies of Slobodan Milosevic, which resulted in genocide in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Serbia’s nationalist establishment constituted the “First Serbia” against which the “Other Serbia” or “Second Serbia” defined itself. Perovic was Serbia’s foremost historian of political thought, the author of a monumental three-volume work, “Serb Socialism in the 19th Century,” which was published from 1985 to 1995 (although her academic work has never been published in English).

Perovic’s status as the Other Serbia’s foremost figure was due not only to her intellectual talent but because she had, as secretary of the League of Communists of Serbia (SKS), been one of the two leading figures of the “communist liberal” regime that governed Serbia from 1968 until October 1972, at a time when Serbia was a constituent member of the federal state of Yugoslavia, alongside her mentor, Marko Nikezic, president of the SKS.

This regime, perhaps the most progressive in Serbia’s history, sought to liberalize the Serbian communist order both politically and economically, while opposing Serbian nationalism — but without resorting to repression. It represented a bold attempt to develop a pluralistic political culture for Serbia, one that could have inoculated it against the coming ultranationalist virus. It looked to the liberal West, while viewing the Soviet Union as the citadel of the authoritarian communism it was opposing.

Yet to Josip Broz Tito, the communist dictator of Yugoslavia, the Serbian liberal communists appeared a threat — both because they seemed to be dismantling the hegemony of the ruling communist party (the League of Communists of Yugoslavia) and because they permitted Serb nationalist discourse that threatened the multinational coexistence upon which Yugoslavia depended. Tito’s purge of Nikezic, Perovic and the Serbian liberals in 1972 ensured that Serbia would remain on an authoritarian path.

The purge consolidated the Serbian communist authoritarian elite that would spawn Milosevic’s dictatorship. Among the more conservative Serbian communists who consolidated power after the purge were Dragoslav Markovic, whose niece Mirjana married Milosevic, and Petar Stambolic, whose nephew Ivan was Milosevic’s political mentor and personal friend, responsible for his rise to power. Milosevic would, however, establish his power by turning against Ivan Stambolic and sidelining or subordinating other old-school Titoists. Even so, he was a typical senior apparatchik of their system until he seized control of it in 1987. Under Milosevic’s control, the Serbian communist regime transitioned seamlessly from Titoism to nationalist authoritarianism. His Socialist Party of Serbia, created in July 1990 from a merger of the SKS and its partner organization, the Socialist Alliance of Working People of Serbia, easily won the first post-communist multiparty elections in Serbia in December of that year. Although hardly fair given the regime’s domination of the media, the electoral victory undoubtedly reflected a popular endorsement of Milosevic’s authoritarian and nationalist policies. The liberal communist experiment of 1968-72 was a missed opportunity for Serbia to develop along liberal-pluralist rather than authoritarian and, eventually, nationalist lines. Had this different path been followed, the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s might have been avoided.

Following her 1972 removal from power, Perovic abandoned her political career and devoted her life to historical study. Her research focused on the history of the Serbian socialists and of the mighty People’s Radical Party that had begun in the 1870s as socialist but developed along populist and nationalist lines. Svetozar Markovic, the party’s Russian-educated founder, saw the purpose of socialism as avoiding evolution along Western liberal-capitalist and industrial lines and preserving and rejuvenating Serbia’s traditional, egalitarian, peasant-based communal society. The party that he founded moved away from socialism after his death but retained his anti-Western, anti-modern orientation. It became Serbia’s most popular political party by the 1880s, ultimately presiding over the country’s conquest of present-day North Macedonia and Kosovo in the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the establishment of the ill-fated Yugoslav kingdom under Serbia’s domination in 1918. Whereas Serb nationalists had traditionally viewed this history in terms of patriotic achievement, Perovic focused instead on the populist, anti-pluralistic, anti-modern character of the party and its ideology.

The People’s Radical Party identified itself with the Serb nation in its entirety, rejected the legitimacy of political alternatives and, in the person of its longtime leader, Nikola Pasic, identified also with tsarist Russia rather than the West. The Radicals established the tradition of belief in the “party-state”: the identification of all legitimate national life with a single party. The Serbian Communists, later Milosevic’s Socialists, inherited this tradition. Perovic, by contrast, identified with Serbia’s Progressive Party, founded in the 1880s in competition with the Radicals. The Progressive Party favored Serbia’s development and modernization along Western and liberal lines; it prioritized individual liberty and the separation of powers over unfettered majority rule. It was in the Progressive tradition that Perovic saw a positive Serbian alternative to populist, anti-pluralist, authoritarian nationalism. As she wrote, the Radicals aimed at a “people’s state” in which “social equality and national unity were merely two manifestations of the same ideology,” while the Progressives aimed at a “legal state.”

For historians of the Other Serbia, the path to a better Serbia required dismantling the patriotic cliches that infused the mainstream nationalist perception of Serbia’s history. Among the most brilliant of the second generation of historians from this tradition was Olga Popovic-Obradovic, who went for the jugular of Serbian nationalist historiography, deconstructing the myth of a “Golden Age” of Serbian parliamentarism in the period 1903-14. Traditionally, historians had suggested that, following the destruction of the ruling Obrenovic royal dynasty in a coup in 1903, power had passed to the Radical party, Serbian parliamentary politics had flourished and Serbia had emancipated itself from Austro-Hungarian influence and set about the pursuit of “national unification and liberation” (i.e., territorial expansion).

In her groundbreaking work “Parliamentarism in Serbia 1903-1914,” published in 1998, Popovic-Obradovic demonstrated that this was, in fact, an era when a clique of Serbian army officers, eventually constituted as the “Black Hand,” interfered in politics, toppled ministers and terrorized politicians and journalists, while the Radicals and their political rivals brutally demonized each other, accused each other of treasonous dealings with foreign powers or conspired with the aforementioned army officers against each other. The Radicals even occasionally murdered their opponents. This state of affairs significantly contributed to the outbreak of war with Austria-Hungary in 1914, triggered by the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which prominent members of the Black Hand had orchestrated and which the Radical government had failed to prevent. This conflict, which grew into World War I, wiped out a large part of Serbia’s population and very nearly ended its independent national existence. Therefore, far from being a “golden age” of parliamentarism in Serbia, this was a period of vicious internal political struggle, largely extra-parliamentary and extra-constitutional in character and catalyzed by extreme nationalism, culminating in disaster for the country.

The name “Other Serbia” arose from the title of a collection of essays published in 1992, in which Perovic had depicted Milosevic’s authoritarian-nationalist regime as the expression of a historic failure of Serbian modernization. She noted: “It is necessary not only to point out the true essence of the symbiosis of state socialism and nationalism, but also to create an alternative to it. Even if it is not formally designated as the ‘other Serbia,’ this alternative will inevitably be that.”

She wrote these lines before Milosevic’s authoritarian-nationalist regime had dragged Serbia to its lowest point. This came in 1999, when his extension of his murderous policies to Kosovo triggered NATO’s intervention and bombardment of Serbia, forcing its withdrawal from the territory. Milosevic’s discredited regime was overthrown the following year in an uprising that combined a popular mass mobilization with an elite putsch. His successors in power were divided over whether to continue his brand of nationalist policies or pursue rapprochement with the West and reform along liberal-democratic lines. Milosevic was replaced as president of the “Federal Republic of Yugoslavia,” comprising Serbia and Montenegro, by another hard-line nationalist, Vojislav Kostunica, while Zoran Djindjic, who was committed to liberal reform and a Western orientation, became the prime minister of Serbia.

Djindjic had Milosevic arrested in April 2001 and deported to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in June of that year, but this bold break with the past was curtailed when Djindjic was assassinated in March 2003 by former members of the Red Berets, Milosevic’s erstwhile special forces, who were deeply implicated in his atrocities.

Serbia remained divided between authoritarian-nationalist and liberal-reformist impulses, but it was the former that gradually predominated, culminating in the current regime of Aleksandar Vucic, a counterpart of populist demagogues elsewhere like Orban, Erdogan and Netanyahu. For Perovic, Vucic’s party was the ideological heir to Nikola Pasic’s original Radical party. It was, in her words, “a political party that rejects Western Europe, insists on a national state, on national unity, on the completion of the national ideal, on accepting European institutions that it empties of European substance and that serve it more as a cover.”

In the meantime, Montenegro, alienated by Serbia’s nationalistic obstruction of the federation’s integration with Europe and the West, broke away to become an independent state in 2006, while most principal Western states recognized the independence of Kosovo in 2008. Serbia’s neighbors Bulgaria and Romania had been on the losing side in World War II and, during the Cold War, they were much poorer than Serbia and were ruled by more brutally hard-line communist regimes. Yet they joined NATO in 2004 and the EU in 2007, while Serbia, whose population is largely proud of its role in the fight against Nazism, remains outside both organizations, owing to its inability to repudiate Milosevic’s legacy and transition to a post-nationalist politics; it was very slow to cooperate with the ICTY and is still unwilling to recognize Kosovo’s independence. Serbia’s bitter nationalists, like their Radical counterparts of a century before, look to Russia as their natural ally and today largely support Putin’s war against Ukraine.

For Perovic and Popovic-Obradovic, Serbia’s post-Milosevic evolution confirmed the difficulty of reforming it along liberal-democratic lines. Popovic-Obradovic wrote in 2004 of the burden of Serbia’s anti-pluralist, ultranationalist legacy:

Mostly morally indifferent to the issue of responsibility for war and war crimes, the electorate in Serbia continues to trust promoters of war policy, the individuals and parties of ultra-nationalist and populist provenance, misled by their nationalist rhetoric, sugary archaism and mythomania, as well as by their social demagogy of anti-capitalism and anti-Westernism in general.

Tragically, she died of cancer less than three years later, at the age of 52.

The legacy of Perovic and Popovic-Obradovic is continued by talented Serbian historians challenging the hegemonic nationalist paradigm, including Dubravka Stojanovic, Milivoj Beslin, Branka Prpa, Olga Manojlovic-Pintar and others, as well as by the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, which publishes many of their anti-nationalist essays. Today, Vucic’s regime continues to pursue an irredentist policy in its relations with neighboring countries. It has supported attempts by Serb nationalists among the Serb minorities in Kosovo and Montenegro to destabilize those countries and undermine their independent statehood, while supporting the regime of Milorad Dodik in Republika Srpska, Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Serb entity, which is openly and actively working to break up the country. Vucic’s regime also refuses to impose sanctions on Putin’s Russia over its invasion of Ukraine and abuses democratic process and the free media in Serbia. The Second Serbia remains an honorable but politically marginalized alternative.

In many ways, Serbia’s neighbor Croatia followed a similar trajectory. Like Serbia, Croatia was a member of the Yugoslav federation and governed by a liberal communist regime in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a period culminating in the so-called “Croatian Spring,” a democratic flowering similar to the Prague Spring of Alexander Dubcek’s Czechoslovakia before it was crushed by Soviet tanks in 1968. Like its Serbian counterpart, the Croatian liberal communist leadership in 1971 was toppled by Tito in the name of restoring a more authoritarian communist order.

This produced a long-term democratic deficit and had negative repercussions for Croatia and Yugoslavia in the late 1980s, when Milosevic’s regime assaulted the Titoist federal Yugoslav order, suppressing the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina (an autonomous province in the northernmost part of Serbia) and deploying the Yugoslav army to crush Kosovo Albanian resistance before seeking to recentralize the Yugoslav federation under Serbia’s domination.

Though this clearly threatened Croatia, it was its northwestern neighbor Slovenia that spearheaded Yugoslav resistance to Milosevic. Croatia, broken by the purges of the early 1970s, was characterized during this period by the so-called “Croatian silence,” whereby its communist leadership sought to avoid anything that could be construed as Croatian national assertiveness. Its leading communist, Stipe Suvar, was an authoritarian hard-liner who sought coexistence with Milosevic. Yet when communist one-party rule ended in Croatia in 1990, the subsequent free elections were won by Franjo Tudjman and his nationalist, anti-communist Croatian Democratic Union. Tudjman was himself a historian and had been persecuted and imprisoned during the suppression of the Croatian Spring, but in office he replicated Milosevic’s authoritarian nationalism. A former communist, he continued to revere Tito in certain ways and emulated him, even down to his taste in ceremonial uniforms.

Following the 1990 election victories by anti-communist nationalists in Croatia and Slovenia, the Serbian regime definitively abandoned support for a unified Yugoslavia and sought forcibly to expel both republics from the federation, while at the same time seeking to violently dismember Croatia and establish Serb ownership and control over a large portion of its territory. Though Serbia’s military aggression against Croatia forced a reluctant Tudjman to lead a defensive war against Belgrade, his overriding impulse was to reach an accommodation with Milosevic, his fellow post-communist authoritarian-nationalist strongman, involving the partition of neighboring Bosnia-Herzegovina. This led to talks between Tudjman and Milosevic in March 1991 at the settlement of Karadjordjevo in Vojvodina, at which the possibility of Bosnia’s partition was mooted. By a quirk of history, it had been at Karadjordjevo where Tito had met with the Croatian liberal communists in 1971 to inform them of the end of their political experiment.

Tudjman’s instinct for collaboration with Milosevic led him to restrain and obstruct Croatia’s efforts at self-defense from Serbian aggression in 1991, ending eventually in Croat forces fighting against the Bosnian army as the junior partners of Serb forces in the latter’s genocidal project of destroying Bosnia-Herzegovina. This was, from the standpoint of Croatian national interests, not only immoral but suicidal: The defeat of Bosnia before August 1995 would have ended the war with Serb forces still occupying nearly a third of Croatia. This would have meant Croatia’s partition in the manner of Cyprus after Turkey invaded and occupied its northern third in 1974 — the international community’s continued recognition of Cyprus’s territorial integrity on paper has had no effect on the ground.

Some of Tudjman’s (and Milosevic’s) toughest and most determined opponents came from the ranks of historians. The most prominent of these was Ivo Banac, author of the seminal 1984 work “The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics.” While most Western scholars of Yugoslavia assumed simplistically that Serb nationalism, Croat nationalism and the nationalisms of each Yugoslav people were monoliths, Banac demonstrated that the differences between national ideologies within each nationality were as important as those among the different nationalities. For example, Serbs were divided between supporters of “Greater Serbia” and supporters of a unitary Yugoslav nationhood, between those who wanted to emphasize the Serbs’ distinctiveness and superiority and those who wanted to dissolve the distinctive Serb, Croat and other nationhoods in a homogeneous Yugoslav whole.

Like Perovic and Popovic-Obradovic, Banac understood the importance of pluralism and the danger represented by any attempt to homogenize a nation behind a uniform national ideology. He could not forgive Tudjman for squandering a historic opportunity to create a positive Croatia rejecting chauvinism and intolerance:

[Tudjman] entered the untouched structure of a failed regime without a revolution, without blood, even without a demonstration that would provoke a reaction from the still active police of that same regime. This was to his advantage, but only under one condition: that he directed the burgeoning national energy in the direction of creating a healthy society, a free and independent country, with strong representative, economic and defence institutions, with all the features of a democratic culture, with sincere respect for all moral norms, laws and rights, which are valid for every human being. Had Tudjman accomplished this task, naturally with the help of all that is good in the Croatian people, he would certainly have been one of the greatest characters in our history, and his work would survive. But he squandered that chance.

Banac opposed Tudjman’s efforts at ethnonationalist homogenization of the Croats, instead arguing that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s unique tradition as a multiethnic community of Serbs, Croats and Muslim Bosniaks had to be respected; Bosnian Croats had to be understood as part of that traditional Bosnian multiethnic community, not simply as part of a homogeneous Croat nation destined to be annexed to the Croatian state. Many other prominent Croats opposed Tudjman’s anti-Bosnian politics, and Croatia was much more divided over its aggression against Bosnia than Serbia was. Critics included figures as senior as Gen. Martin Spegelj, Croatia’s former defense minister and founder of its army, and Stjepan Mesic, who would succeed Tudjman to become independent Croatia’s second president. As Banac noted in January 1993, “The Bosnian policy of Dr. Tudjman is one of the greater catastrophes of Croatian policy in the twentieth century. Of that, there is not even the shadow of a doubt.” He published a letter in the New York Review of Books in August 1993 with three other Croat intellectuals, including the historian Branka Magas, stating that:

We feel a particular duty to demand of the Republic of Croatia that it support fully and unconditionally the independence, sovereignty and integrity of Bosnia-Herzegovina, in accordance with the democratically expressed will of its people and Croatia’s own past declarations.

The letter went on to condemn the Bosnian Croat separatist entity established by Tudjman and his supporters on Bosnian territory as “an instrument of territorial aggression upon Bosnia-Herzegovina,” while “recognizing the government in Sarajevo as the only legitimate source of authority in the country, sincerely cooperating with all its efforts to defend the country, and promoting its cause in all international forums.”

Similarly, Banac emphasized Croatia’s own tradition of multiethnic coexistence involving Croats, Serbs and others, rejecting the tendency of Tudjmanite Croat nationalists to view Croatia’s Serbs as an unwanted, alien national element. In October 1996, following the end of the war, which had resulted in the exodus of much of Croatia’s Serb population, he delivered the keynote address at a conference called “The Serbs in Croatia — Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow” organized by the Croatian Helsinki Committee in Zagreb, in which he made the point that Croatia was a pluralist historical community and the Serbs were part of Croatian history, that “Croatian state independence will not be complete if it does not accept the Serbs too” and that “the return of the Serbs is desirable from the standpoint of Croatian interests.”

Like Perovic and Popovic-Obradovic, Banac witnessed the vindication of his critique. In the Dayton Peace Accords of November-December 1995 that ended the war in Bosnia, the Bosnian Croat separatists did not receive the territorial entity on Bosnian soil that they had fought for, unlike their Bosnian Serb separatist counterparts, whose Republika Srpska was legalized. But Croatia remained burdened by its Tudjmanite legacy. Its unwillingness to cooperate with the ICTY meant that, despite having been one of the most liberal and prosperous communist polities in Europe before 1990, it joined NATO only in 2009 and the EU in 2013, considerably later than Romania and Bulgaria, while the ICTY in 2013 convicted senior Bosnian Croat officials of serious crimes and implicated the deceased Tudjman himself in a “joint criminal enterprise” to remove the Muslim population from Croat-controlled areas of Bosnia. While Tudjman did not achieve his dream of partitioning Bosnia and establishing a Greater Croatia, he will be remembered in history as a co-perpetrator in Milosevic’s murderous aggression.

Banac died in 2020, yet other Croatian historians such as Ivo Goldstein, Tvrtko Jakovina and Josip Glaurdic continue to challenge Croat nationalist paradigms. Serb and Croat opponents of the partition of Bosnia have collaborated for decades. In a contribution to a collection of essays honoring Banac, published shortly after his death, Sonja Biserko, president of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, noted his observation that “the roots of the breakup of Yugoslavia lie in the 1970s, when Croatia and Serbia, as the two largest republics, offered new solutions” and commented, “He considered it a big mistake that the Serbian liberals, as the most European leadership of Serbia, were ever replaced. The same can be said for Croatia.”

Despite an attempt under Mesic to steer Croatia toward a friendlier policy vis-a-vis Bosnia-Herzegovina, today Croatia continues to aggressively meddle in the latter’s internal affairs. Its current president, Zoran Milanovic, openly sympathizes with Putin and even threatened to obstruct Sweden and Finland’s entry to NATO unless Croat nationalists in Bosnia received appropriate concessions.

For many post-communist countries in Europe, the journey to functioning liberal democracy with a pluralistic political culture has been long and difficult, and remained incomplete as Putin began openly assaulting the liberal-democratic European order and offering an alternative banner to which authoritarian nationalist populists could rally. Against these resurgent nationalist populists, the remedy remains that for which Perovic, Popovic-Obradovic and Banac fought: a pluralism that respects the legitimacy of multiple political currents and the rights of minorities at home, and the sovereignty and territorial integrity of neighboring states abroad.

Today, Serbia continues to view Kosovo and Montenegro — and both Serbia and Croatia view Bosnia, and Bulgaria views Macedonia — the way Russia views Ukraine: through a nationalist prism, as the object of its ambitions. Domestic opponents of this nationalism are widely viewed as traitors, which dovetails with a climate of intolerance toward freedom of expression. In Serbia, journalists and human rights activists are regularly harassed by regime-backed nationalist thugs. Last year, after a nationalist tabloid falsely accused her of calling for violence against the president when she criticized Vucic’s policies toward Russia and Kosovo, the Serbian journalist Jelena Obucina received threats on Twitter that she would suffer “impalement” and be “burned.”

In Bulgaria, representatives of the country’s ethnic Macedonian minority, which the government and state refuse to recognize and seek forcibly to assimilate, last year reported a dramatic increase in harassment by the authorities or at their instigation. This trend was linked to Bulgaria’s irredentist policy toward Macedonia, which has involved attempts to force it to rewrite its history along Bulgarian nationalist lines as the price for EU membership. Journalists in Bulgaria are regularly harassed by the authorities or at their behest. Atanas Tchobanov, who investigates corruption, reported last year that, after receiving threats, he had to wear a bulletproof vest for a month. He eventually moved to France.

In Croatia, President Milanovic last year publicly denounced as traitors Croats who support sanctions against Milorad Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska, who is his ally in his anti-Bosnian, anti-Bosniak policy. Journalists in Croatia are periodically threatened and harassed. Tea Paponja was violently assaulted in 2021 after attempting to investigate people burning a Pride flag at a Pride march in Zagreb. In July 2023, the International and the European Federations of Journalists condemned a Croatian government bill aimed at severely restricting journalistic freedom.

So long as these conditions persist, these countries cannot complete their transitions into genuine liberal democracies, and southeastern Europe cannot escape conflict and instability. This is, after all, a European and not merely a Balkan struggle. With Europe’s liberal-democratic future being defended on the battlefields of Ukraine, the struggle is more urgent than ever.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.