As I continue to watch with horror the forced exile of refugees from places where home has become an unsafe harbor, I am transported to my childhood, when our home in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, suddenly became unsafe and we fled as a family in search of a haven. We did end up finding refuge, thanks to communities of Turks and Albanians in Macedonia, who extended what they culturally understood as “besa”: an Albanian code of honor entailing pledges of protection, safe harbor and safe passage, particularly for those in danger.

On May 2, 1992, our bus was one of the last to leave Sarajevo. I rode it with my mother and two younger brothers, in an evacuation effort for the families of employees of the Islamic Community of Bosnia and Herzegovina. I was 10 years old.

On that day, the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) and Bosnian Serb rebel forces launched an attack on Sarajevo in an effort to capture it. Supported politically, militarily and logistically by the neighboring country of Serbia, Bosnian Serb rebels sought to break away from Bosnia and establish a state of their own. Serbs, who are predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christian, are the second-largest ethnic group in Bosnia. The rebels’ ultimate goal was to join Serbia. Led by Radovan Karadzic, they had put their secession plan in motion shortly after Bosnia voted for independence from the former Yugoslavia on March 1, 1992. What ensued was a campaign of genocidal violence against the Bosniak population across the country.

In order to strike a deadly blow against the newly independent country, the rebels intended to capture Sarajevo itself. A decisive battle for the defense of the capital began on the very day of our departure. The Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina repelled the attack. Failing to capture the city, Serb forces laid siege to it for the next three-and-a-half years.

We drove southeast for many hours before ultimately reaching Macedonia. While some families on the bus stayed in the Macedonian capital of Skopje, most of us headed west. We wound up in the northwestern town of Tetovo — home to a sizable Albanian population as well as a Turkish minority — not knowing what lay ahead.

The Albanian families in Tetovo had expressed their willingness to host Bosniaks, which was the key reason why this town became our temporary home. Unlike the rest of Yugoslavia, Macedonia, which had declared independence in 1991, was still peaceful. We hoped this would be our refuge for the next several months. In Tetovo, Albanian and Turkish families took the families arriving from Bosnia into their homes. While some Bosniaks had acquaintances in the town, we ourselves knew no one at the time. But one Albanian-Turkish family who had heard of my father warmly offered to take us in.

My late father, Fikret Karcic, was among the most respected and prolific scholars of Islamic law in the Balkans. At the time of our arrival in Macedonia, he was an assistant professor at the Islamic Theological Faculty (now called the Faculty of Islamic Studies) in Sarajevo. Established in 1977 in what was then communist Yugoslavia, it was at the time the only institution of Islamic higher learning in the country. Its aim was to educate a new generation of religious scholars who, by studying in their home country, would no longer need to travel abroad for their education. The country’s communist regime, in power since 1945, had clamped down on religion and religious education, and the Gazi Husrev Bey Medrese in Sarajevo was the only institution for educating imams in Yugoslavia. While less harsh than other communist regimes, Marshal Tito’s Yugoslavia still marginalized both religion and devout citizens.

As the only institution of its kind in Yugoslavia, the Sarajevo school attracted students from all parts of the country. Bosnian Muslims, ethnic Albanians, Turks and others studied in Sarajevo before taking up jobs all across Yugoslavia. By the same token, Muslims of various ethnic stripes from Macedonia had also studied in Sarajevo, which is how they had learned of my father. Thus did this particular family volunteer to host us upon our arrival in Tetovo.

The Macedonian authorities were visibly unhappy that Albanians were assisting Bosniaks. I still remember their attitude vividly. Three decades have passed since that time, but I am still wary of placing the relatives and descendants of my former hosts at any potential risk, and so will refer to them by the pseudonyms Skender and Fatime. The former was an entrepreneur and the latter a homemaker. For the six months we stayed with them, they took us in as part of their own family. Though they never expressed it formally, Skender and Fatime gave my family what was essentially besa.

Besa is an important concept in Albanian culture. The word has several meanings. Literally, it means “to keep a promise.” It is a code of honor. It can also mean an oath, a pledge or an allegiance. If you are given besa, you are provided protection.

It is an old concept and practice. Albanians were noted for providing such protection to others on several occasions throughout the 20th century. During the Holocaust, Albanians gave besa to the entire Albanian Jewish population, as well as other European Jewish refugees. According to Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Albania, “the only European country with a Muslim majority [at the time], succeeded in the place where other European nations failed. Almost all Jews living within Albanian borders during the German occupation, those of Albanian origin and refugees alike, were saved, except members of a single family. Impressively, there were more Jews in Albania at the end of the war than beforehand.”

Later, during the international armed conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bosniak refugees from the country were given besa by the Albanian community in Macedonia. A few years after that, when Slobodan Milosevic’s regime intensified a campaign of terror against Kosovar Albanians, thousands sought refuge in Macedonia and Albania in 1999. There again, Albanians offered besa.

In my case, long before I had ever heard of the concept of besa, my family and I experienced it. Other Bosniak families who came to Macedonia with us, as well as many who poured into the town in the following weeks, were similarly given besa by other Albanian families.

As the war raged in Bosnia, refugees kept arriving in Macedonia. The country’s officials and bureaucrats made no secret of their displeasure at the influx of Muslim refugees. But it was the Albanian and Turkish families who bore the burden of hosting long-term guests. Many perceived their role as akin to that of the Ansar — the Arabic term, literally meaning “helpers,” given to the people of Medina who provided shelter and support to the Prophet Muhammad and his followers after their departure from Mecca in 622 CE.

I remember clearly when my family members from the eastern Bosnian town of Visegrad — my grandmother Hafa, my great-grandmother Hafiza and my paternal uncle and his family — arrived that summer of 1992. They showed up in Tetovo one day and the sight of Hafiza stirred emotions among all those present. Remarkably tall, with a gentle face, Hafiza was then in her late 90s. Throughout the 20th century, her life had been punctuated by repeated Serb attacks on Visegrad and its Muslim population. The existential threats to Muslims in eastern Bosnia came both from next-door neighbors and attackers from Serbia.

What was remarkable about Hafiza’s fate was that she was forced to flee Visegrad three times in her life: in World War I, World War II and once again in 1992. Tetovo was her third — and, it would turn out, final — refuge over the nine decades of her life.

Still, my cousins were lucky to make it out of Visegrad at all. We had a partial family reunion that no one had expected. These relatives were also provided with accommodation and support by local Albanian and Turkish families, who chose which arriving Bosniak families they would host. Since most Bosniaks knew no one in Tetovo, they ended up living with Albanian families they had never met before.

It soon became clear the war would be a prolonged one, with no return home in the foreseeable future. Understanding this new reality, many Bosniaks lived in Tetovo for several months before making their way to new destinations across Europe.

My father rejoined us in late 1992. Before the war started, he had been scheduled to take up a visiting professorship in Istanbul. His arrival in Tetovo allowed us to prepare to move on to Turkey. On hearing of his arrival, several of his former students and acquaintances came to see him. They had known him as a professor and rising public intellectual, prominent among the younger generation of Muslim thinkers active in the Islamic community of Yugoslavia.

One experience in particular stands out.

A local former student from Tetovo, who I will call Ismail, came to see my father and warmly invited him to his village. This was a gesture of reverence for a former teacher. For Bosniaks, as in many other cultures, to invite someone to visit a family home reflects both respect and closeness.

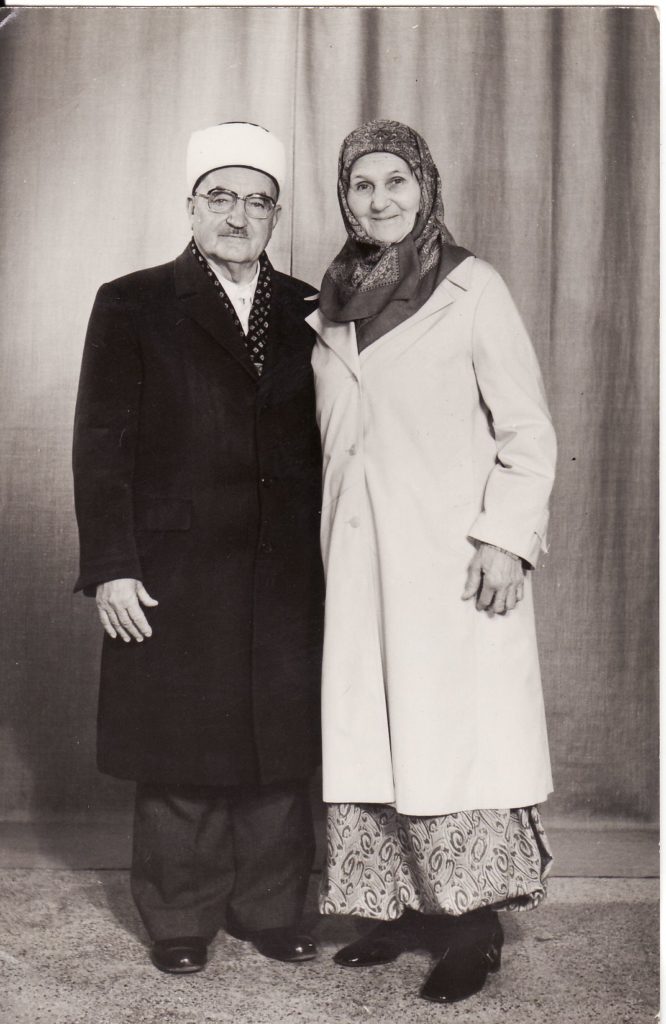

Before the war, Ismail was a student in Sarajevo. As part of his religious education, he and the other students were sent across Yugoslavia to serve as imams in local communities, a practice intended to compensate for the paucity of imams in communist Yugoslavia. To serve as a temporary imam in a community also offered valuable experience for future spiritual leaders. The Islamic Community assigned Ismail to serve in my father’s hometown of Visegrad. My father’s maternal grandfather, Rasim Tabakovic, had been an imam in the town for 40 years and was the pillar of the local Muslim community. My father’s parents — Hasan and Hafa — were observant Muslims deeply committed to their mosque and local community in Visegrad. They were hosts to countless Muslim travelers passing through or visiting. During the long years of communist rule, few Muslims came to Visegrad without dropping by my grandparents’ home. Ismail was one of the many my grandparents hosted.

Now, years later, Ismail invited my father to visit his village. His family was religious and of modest means. After touring the village and Ismail’s parents’ home, my father was taken aside by Ismail’s elderly father so that no one could hear or see their interaction. Though living modestly, the elderly Albanian gave my father a gift: a bundle of his family’s gold. He told my father that this was what they had, and he wanted us to keep it “for a rainy day.” The symbolism of the act and the readiness to sacrifice was more powerful than the quantity of gold, which was humble.

Gold is especially valued among people in the Balkans. To gift gold at marriage ceremonies is part of the culture and protocol. It is handed down from mother to daughter. Given the region’s turbulent history, many in the Balkans have long kept gold at home as a way of hedging their assets. For many families, the gold kept at home is both symbolic and significant.

Now, Ismail’s father gifted my own father his family’s gold. I consider this, in effect, a second besa.

Not long afterward, we packed our bags once again. My mother and brothers and I had been in Tetovo for six months. After my father rejoined us, we moved together to Turkey. My father taught for a year at Istanbul’s Marmara University, before we relocated even further east to Malaysia. We had briefly lived in this part of southeast Asia before, in 1990, and were now back in Kuala Lumpur. The capital would be our home for the next eight years.

My family was fortunate in managing to establish a livelihood for ourselves in foreign lands. My father was a professor at the International Islamic University in Kuala Lumpur from late 1993 to 2002. This meant we never did have to sell any of that precious gift we had received: The gold offered by Ismail’s father stayed intact with us.

My fellow Bosniak people suffered a genocide and our homeland was destroyed by the war that ravaged Bosnia until 1995. Then, in 2002, after a decade abroad, my family decided to return to Bosnia. My father started teaching again at the Faculty of Islamic Studies and the Faculty of Law in Sarajevo.

A few years later, there was a conference in Sarajevo, in which Ismail came from Macedonia to participate. During that meeting after so many years, there was one important issue to settle. My parents had kept the gift of gold all those years while living abroad. Now, my father gave it back to Ismail, whose family had been sincere in giving away what they had and never expected to receive it back from us.

Our host in Tetovo, Skender, died at a relatively young age. But Fatime lived to see us return to Bosnia. In 2006, some 14 years after we had stayed in her home, Fatime was now my family’s guest at our home in Sarajevo. This time, my parents returned the genuine, gracious hospitality our Albanian hosts had offered us in the early 1990s. I last saw Fatime when she visited Sarajevo again a few years ago. I was very glad to see her. She had become like an aunt and a part of our family. She died not long after visiting us.

The memories of Albanian and Turkish hospitality and support to Bosniaks in Macedonia in 1992 live on in both communities. Yet the remarkable stories of one community’s sacrifice have been lost to the broader world, as most of the focus has been on the Western response to the refugee crisis stemming from the genocide in Bosnia. This focus has neglected to shine light on the remarkable acts of generosity by humbler people.

Albanians’ besa to Bosniaks was not a top-down decision. It was a grassroots, people-to-people, humane response to an ongoing genocide. Nor was it the only time Albanians had acted this way in the 20th century. It is a testament to the power of an informal code of conduct and a reminder that acts of immense faith and hope do take place.

Skender and Fatime offered their home to strangers, refugees who were fleeing for their lives to a place most did not know. Ismail’s father was willing to give away his modest family’s scarce assets. These were outstanding acts of generosity. They, along with the other Albanian and Turkish families in Tetovo, were the Ansar of the 1990s. Besa is a special and singularly deep commitment to the protection of others. It is an informal code of honor that, once someone has undertaken it, they will continue to honor even at great personal risk to themselves. It is this spirit of providing besa that perhaps needs more cultivation in welcoming refugees in other places today. If more people adopted it, the world’s refugee situation would look very different indeed.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.