“During our time in Tunis, we rarely ventured into the city center. Certain areas were off-limits, and whenever we did walk there, we were faced with harassment and trouble. Occasionally, the police stopped us near their stations.” This is how Ahmed, an unemployed man in his 20s from the Helel neighborhood in Tunis, describes his life before he emigrated five years ago. Ahmed attributes the security forces’ actions to his appearance — his facial features, hairstyle and clothing — which identified him as a resident of a low-income neighborhood. These neighborhoods are often influenced by trends established by North African immigrants in France.

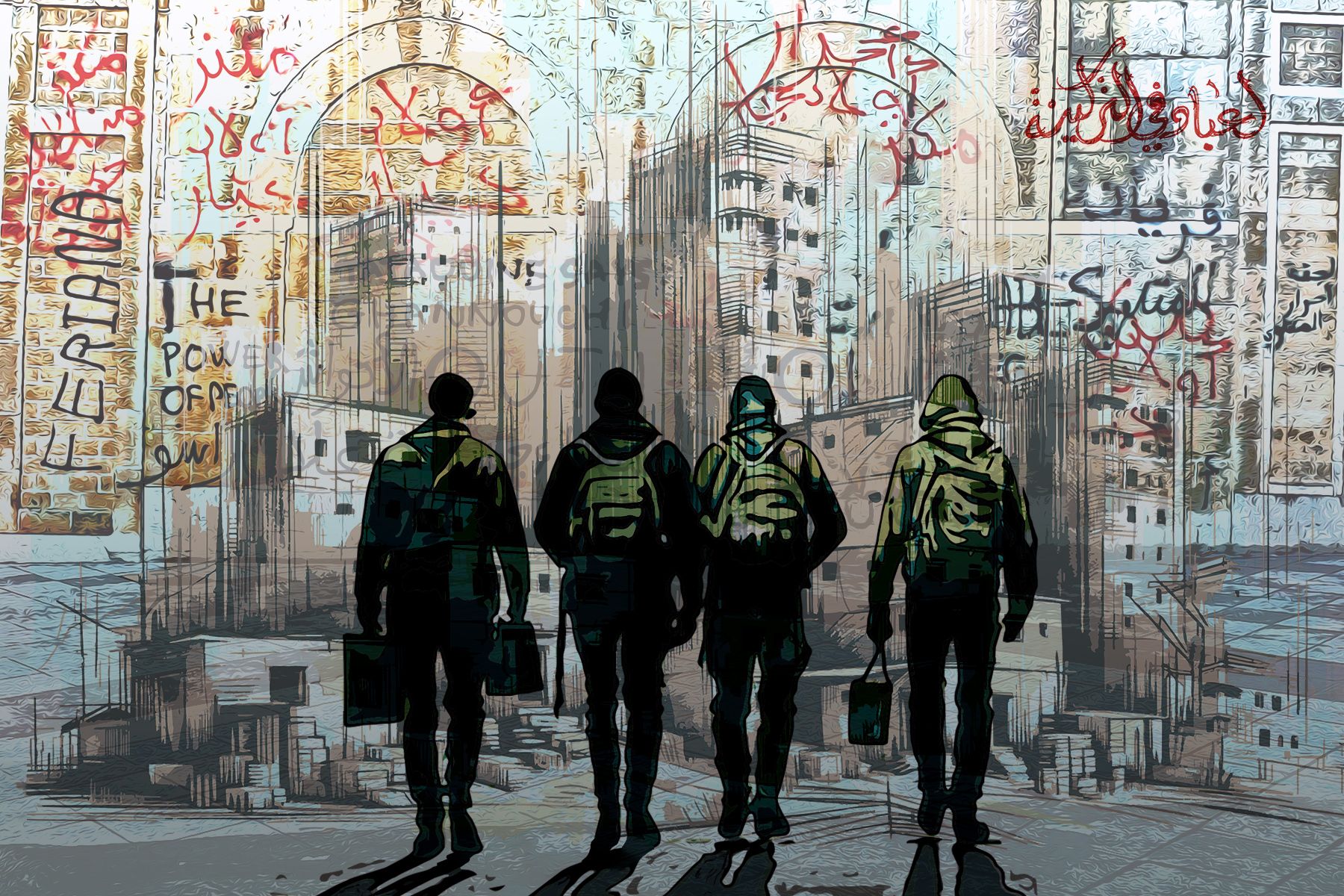

This was Ahmed’s daily reality before he decided to leave the country. He adds, “In Helel, emigration is not a luxury, but a necessity to escape the poverty in which we live.” Ahmed’s situation is not unique; it mirrors the experiences of thousands of young people in the underclass neighborhoods of Tunis. They are stigmatized as being prone to violence, and labeled “hogra” (the contemptible), a term that has gained traction over the past three decades as a marker of disdain toward the underprivileged. The term encapsulates within it much of the exclusion, ostracism and marginalization of the poor in Tunis.

But this is not a new phenomenon. My research has shown that these underprivileged areas have long historical roots and have been affected by the politics and policies of many eras. In the 10th century, the ruling Fatimids prohibited Jews from living inside the city walls; the beys of the Ottoman Era divided the city into three classes; the French colonial era saw mass urbanization, which led to huge growth of the slums; and independence in 1956 continued that trend, leading to the situation we see today in low-income, marginalized communities. The “contempt” drives young people like Ahmed to emigrate, but in a recent twist it has also been absorbed into the lexicon of protests that seek change.

People from the low-income neighborhoods of Tunis have long been a strong force in the country’s politics. They were instrumental in overthrowing the regime of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali during the Jasmine Revolution in 2011, which itself was ignited by Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation, protesting against the police’s persistent “contempt” for him in 2010. They also played a role in bringing the Islamist-leaning Ennahda movement to power that same year, and they were also a key constituency for President Kais Saied as he gained power in 2019. Despite their political significance, these neighborhoods still suffer from endemic marginalization and isolation, and their young people endure immense hardships simply because of where they come from.

Hogra, while a modern term, descends from a long history of elite disdain for the residents of remote steppe lands, the countryside and smaller towns. In earlier times, these people were labeled as “qaar” (degenerates), “houkesh” (uncivilized) and “jboura” (fools). The centralization of power in Tunisia since the 16th century has spawned a lexicon of derogatory terms that seek to strip people from impoverished regions and neighborhoods of access to social and political power.

However, those labeled as hogra in underclass neighborhoods have begun to use the term themselves, influenced by the cultural movements of marginalized groups in Western societies. Rap music has become one of their forms of expression. In 2005, Ferid El Extranjero released the song “Labed fi Tarkina” (Society in a Dungeon), marking a pivotal moment in Tunisian rap. Ferid, a son of Jbal Lahmar, one of Tunisia’s largest underclass neighborhoods, spoke about the indignity, police oppression and injustice endured by the residents of these areas.

The song begins with a recorded dialogue between Ferid and a neighbor. The neighbor suggests a drive outside the neighborhood: “Let’s go outside, brother, let’s go for a ride.” Ferid declines due to police security campaigns targeting people from underclass neighborhoods, saying: “No, brother. I’ll be stapled to my house today. … It’s better to be bored than in trouble. These snakes [in reference to the police] are getting everyone, you see?”

The song became a sensation and an anthem for these neighborhoods’ residents to confront police repression. They embraced rap and developed their own lexicon, centered on “us” (the people of underclass neighborhoods) and “them” (the residents of upscale areas). This division has fueled a hidden conflict: The affluent view those from underclass neighborhoods as criminals, while the residents of underclass neighborhoods see the wealthy as privileged and their families’ fortunes as built on the effort and sweat of others.

During my research on underclass neighborhoods, I found that these areas have not received much academic or media attention despite their significant role in contemporary Tunisia’s social and economic landscape. The history of underclass neighborhoods in Tunis is often obscure, yet they may be an extension of the “arbad” (residential areas near city walls) like Bab El Jazira and Bab Souika. These neighborhoods were inhabited by the “afaqi” (literally “vagabonds”), a name for marginalized social classes and those from the most remote parts of the country who were displaced from the countryside and interior regions.

Arbad were established during the Fatimid Caliphate in Tunisia in the 10th century, with the founding of neighborhoods such as Mellassine and El Hafsia, which were inhabited by Jews who were prohibited from living within the city. Later, during the reign of the Zirid ruler al-Muizz ibn Badis in the early 11th century, the state witnessed protests led by Shiites dissatisfied that the Maliki interpretation of Islam was the official religion in Tunisia. Mahrez ibn Khalaf, known as Sidi Mahrez and revered today as a saint, launched an attack on orders from the mother of the Zirid ruler. This campaign resulted in the killing of many Shiites, and those who survived were exiled to live in El Hafsia, alongside Jews who were already settled there.

In the mid-11th century, the Banu Hilal tribe marched from the Arabian Peninsula into Tunisia, prompting people from the Tunisian interior, especially the south and southwest, to migrate toward the cities of the northern coast, particularly Tunis. Population density surged, and these cities could no longer accommodate all the displaced. Consequently, they began building housing under the city walls. This led to the formation of densely populated areas on the outskirts of coastal cities and the capital, suffering from poverty and marginalization. Over the centuries, these areas evolved into the underclass neighborhoods we see today.

During the reign of the beys, from the 17th century, Tunisia’s urban division was stratified into three levels: the city center, home to religious leaders, established families, senior army officers and the wealthy; the squatter lands, housing the poor, marginalized and low earners; and the new Jewish neighborhoods located outside the city walls.

The French colonization of Tunisia began in 1881. As in so many instances of settler colonialism, the French authorities confiscated the lands of small farmers. The value of the land rose, and arable land, the mainstay of the Tunisian population, became less available as a result, a situation exacerbated by subsequent droughts and locust plagues, impoverishing thousands of rural people. Under French colonial rule, Tunisia became increasingly industrialized, with economic activity concentrated in the capital. This prompted migration from the interior of the country to Tunis, where industry was booming, resulting in the formation of workers’ neighborhoods. From 1881 onward, Tunisia witnessed the rise of manufacturing and construction industries that required a large labor force. The first informal tin shantytown emerged at the beginning of the last century.

Over time, the population in these slums increased, and poverty and epidemics such as typhoid fever, plague and cholera spread. These conditions led to the displacement of tin slum residents and the demolition of their homes by 1929, pushing them to seek shelter in emerging underclass neighborhoods. These neighborhoods, in the heart of the capital, began to attract marginalized individuals and small craftsmen, becoming a refuge for the displaced, especially when there were family ties to previously displaced workers.

Hardships faced by tribes and rural communities contributed to the growth of these workers’ areas. The colonial authorities transformed cities like Medenine and Tataouine in southern Tunisia into military zones, forcing Bedouin tribes to migrate to the capital. They found footholds in neighborhoods like Helel, Mellassine and Sidi Hussein. Initially, the displacement to these neighborhoods was limited, but it gradually intensified until, by the 1930s, Helel was for example the largest slum in Tunisia.

The story of Helel began in the early 1910s, when it was just a large tract of land owned by a woman from one of the ancient families of coastal Tunisia. Unfamiliar with the area, she appointed a man named Kirish, a notorious brigand, to manage and sell the land. Kirish took control of the entire area, selling plots to newcomers until the neighborhood expanded without an official name. Initially, it was referred to as the Kirish neighborhood. Later, on July 14, 1954, a resistance fighter named Saleh Helel Ferchichi, a member of the Free Constitutional Party, died in clashes with the French colonial army in Bizerte. In recognition of his sacrifice, the Tunisian state named the neighborhood after him, and it became known as the Martyr Saleh Helel Neighborhood. Over time, the name was shortened to Helel (Cite Helel).

The Tunisian historian Hedi Timoumi, in his book “The Social History of Tunisia,” notes that the population of another working-class neighborhood, Jbal Lahmar, actually doubled in a year: from 6,000 in 1946 to 12,000 in 1947. An official report by the French colonial authorities on Jan. 17, 1948, stated that more than 200 “qurbi” (mud huts with tin roofs) were being built weekly in this neighborhood.

Timoumi explains this rapid increase by highlighting the tendency of displaced people to settle where others from their regions had already relocated, bringing with them their customs, values and social dynamics, leading to the presence of tribal and regional formations in the underclass neighborhoods. For example, members of the Frechich Amazigh tribe from central-western Tunisia live in the Ennour neighborhood in Ben Arous, south of Tunis, while the Mthalith and Ouled Ayar tribes from northwestern Tunisia settled in the Helel neighborhood.

After Tunisia’s independence in 1956, displacement to Helel intensified, particularly in the 1970s, following the collapse of the collectivism experiment promoted by socialist policies in the early 1960s. Job opportunities became concentrated in the capital and coastal regions. Ali El Mawlahi, 78, witnessed these changes. Reflecting on them, he says, “When I was born, the neighborhood was already here. But there wasn’t as much chaos or as many people. The past wasn’t all good, though. The facilities you see now — lighting, water and sewage — arrived only in the 1980s, much later than in other neighborhoods of the capital.” The increase in population density led to the rise of “wekalat” — cheap hotels intended for sleeping only.

In his research paper “Reestablishing Urban and Social Life in the Arab Maghreb,” Faraj Stambali argues that the state’s approach to so-called “popular housing” following independence was akin to a policy of social cleansing, aiming to evict residents and force them back to the countryside. The state initially sought to assert its power to maintain the modern face of the city. However, this policy quickly revealed its limitations. Contrary to expectations, the 1970s saw an explosion in uncontrolled public housing growth on the outskirts of major cities.

Fouad Gharabali, a sociologist at the University of Gafsa, explains in an interview that the persistence of such communities on the margins of urban society, both in terms of their work and consumption, stems from their desire to maintain their social space. These neighborhoods were often built without official state control, though sometimes with tacit complicity. The state labels them as “unregulated housing,” while the Tunisian media calls them “secret housing.” In both cases, these neighborhoods stand in stark contrast to the structured and official urban planning standards upheld by state authorities.

Right under the nose of the emerging independent state, the underclass neighborhoods became incubators of political Islam. This was fueled by the radical discourse of the Movement of Islamic Tendency (later Ennahda), which was sympathetic to the poor and residents of impoverished areas, especially young people facing repression and policies that created social isolation. Unable to keep up with the consumption patterns of the capital, these youths saw affiliation with Islamic movements, along with irregular migration and crime, as viable options.

Poverty, overpopulation and historical marginalization have led to Helel being painted in the collective imagination as a hotbed of crime, addiction, theft, pickpocketing and unemployment, resulting in its residents increasingly seen as “despicable people.” Ahmed, a former resident, recounts three different life choices he made while living there. Before the revolution, he had a criminal record for pickpocketing, theft, and assault. In early 2011, during a wave of Islamic awakening among the youth, Ahmed joined the Ansar al-Sharia group, later classified as a terrorist organization. Eventually, he chose the “path of harraga” meaning irregular migration to France.

Ahmed reflects: “When I say I’m from Helel, I’m met with contempt and fear. Why didn’t I get any job? My only choices were unemployment or crime. I don’t want to justify what I did, but this is the reality.” He continues, “When the revolution came and Salafism spread, I thought I would repent, especially since I found people who accepted, understood and talked to me. That’s why I got involved with Ansar al-Sharia, but the story ended when they expelled me. I remained without a future until I decided to emigrate as many others like me have.”

These three intertwined paths of crime, extremism and migration are the limited options available to those in underclass neighborhoods, countering the narrative that choice is available to all. The residents of these neighborhoods suffer not by choice, but as a result of their lack of choice.

A glance at the neighborhood reveals its many problems: homes packed too closely together, arbitrary construction, the absence of paved roads. Helel is absent from the official image of Tunis. Despite being less than a third of a mile from the government’s headquarters, it remains neglected by government interests and calculations, according to its residents.

Life in the underclass neighborhoods of Tunis fosters cultural behaviors and identities distinct from the mainstream. This is reinforced by the hatred generated by security forces’ suppression of the youth in these areas. They are often targeted in public places and the city center because of their clothing or hairstyles, influenced by Algerian and Tunisian teenagers born in France. This targeting also takes place when they attend soccer matches and via routine raids on underclass neighborhoods.

On March 31, 2018, Omar Al-Obaidi, a Club Africain fan, was killed by the police, who forced him to jump into the Meliane River Valley in the Rades region, south of Tunis, despite his pleas that he could not swim. The police responded callously: “Then learn to swim.” Omar drowned, and his death sparked public outrage in the underclass neighborhoods, deepening their hatred for the authorities. The incident reinforced their belief that they were not considered equal citizens and intensified community solidarity and hostility toward wealthier areas.

Tito, a young man in his early 30s from Helel, begins his interview by introducing himself with his nickname. He expresses his disillusionment by narrating his daily struggles, such as the frequent and unexplained water cuts that can last up to three days. In contrast, the Tunisian Water Distribution Co. issues apologies for brief half-hour water cuts in upscale neighborhoods. Tito adds, “When we go to the city center, the police harass me, not others. Every time they check my ID and see I’m from Helel, they ask, ‘What are you doing here?’ Whether it’s coffee shops, the beach, tourist sites or public spaces, we always face contempt.”

The varying attitudes of political elites, government authorities and educated elites toward the people in underclass neighborhoods all reveal clear biases. Political parties and government authorities view them either as a homogeneous electoral base or a potential source of protest. To the security forces, they are a nuisance and a concern. The traditional educated elites see them as idle, jobless individuals whose main goal is to immigrate to Europe, views that stem from a lack of understanding and a readiness to stigmatize and stereotype.

In summary, the people of underclass neighborhoods like Helel face systemic marginalization and endless contempt, both from state authorities and broader society. This marginalization is seen in their treatment by the police, difficulty in accessing public services and the dismissive attitudes of political and social elites. Yet these adverse conditions have actually had a strengthening effect, fostering a solidarity among residents along with deep resentment toward wealthier areas and the authorities who overlook them.

Of course, the people of the underclass neighborhoods are not a homogeneous class but consist of artisans, unemployed, underemployed and so on, a diversity captured in Tunisian researcher and writer Maher Hanin’s book “Resistance Society.” He describes how these neighborhoods are not just places to live but also represent a form of identity, with a strong sense of belonging. Professor Taraki Zannad, from the faculty of humanities and social sciences at Tunis University, has written that these marginal urban spaces spawn a creative social life. They should not be seen only as places of submission but as sites of various forms of protest.

Solidarity in these neighborhoods extends beyond their borders. In Europe, residents from the same neighborhood support new immigrants by providing housing and work. In prison, where social organization is stringent, the administration recognizes the importance of neighborhood affiliations. Instead of dividing wards based on the severity of crimes or sentences, they are organized according to inmates’ neighborhood affiliations, which serves to ensure the continuity of these social bonds even in incarceration.

The slums force us to rethink urban issues in Tunisia, challenging the dominant, security-focused approach. These neighborhoods rarely receive attention except when their residents are blamed during natural disasters, such as floods and building collapses, for the consequences of informal construction. This was evident in 2018 when the minister for equipment, housing and territorial development, Mohammed Saleh Al-Arfaoui, criticized these areas of “chaotic construction.” He overlooked, however, that businesspeople and wealthy individuals in Tunisia built their homes and residential complexes on historical and archaeological lands, violating agreements between the Tunisian state and UNESCO. The state, with its double standard, criminalizes construction violations in underclass neighborhoods while turning a blind eye to grave violations elsewhere.

The Tunisian Constitution of 2014, which included 12 chapters on local governance, aimed at combating centralization and marginalization, whether in underclass neighborhoods or inner cities. Yet it contrasts sharply with the current constitution approved by Saied in 2022, which dedicates only one chapter to local and regional districts. This shift reflects the state’s diminishing interest in underclass neighborhoods and their increasing marginalization.

Life in Helel remains largely unchanged. The neighborhood has expanded and generations of people have moved in pursuit of more forgiving living conditions. But it continues to attract marginalized and deprived individuals. Despite changes in the surroundings, misery remains a constant here. Unlike previous years, which were marked by social movements, marches and protests in underclass neighborhoods, this year appears calm and devoid of any disturbance to the state’s agenda. Many residents have chosen irregular migration over staying in these neighborhoods or remaining silent on the margins. But will this calm last? History tells us to watch these neighborhoods closely.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.