The administrations of both Joe Biden and now Donald Trump have vociferously denounced a growing international legal consensus that Israel has been violating the Genocide Convention. This follows a decades-long pattern of the U.S. government denying, minimizing, downplaying and rationalizing genocide and related crimes against humanity by American allies. Regardless of whether the tenuous ceasefire agreement reached on Jan. 15 holds, investigations will likely reveal more details of Israeli war crimes and more questions about U.S. culpability.

The United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide has been ratified or acceded to by 153 countries, including the United States and Israel, but both governments insist that it does not apply to Israel’s war in Gaza, which, according to a recent study published by The Lancet, may have killed more than 64,000 Palestinians by as early as June of last year. Although that number is impossible to verify, not least because international observers have been barred access to Gaza by Israel, what is certain is that the total number of Palestinian deaths has only risen since.

There is a growing international consensus among leading human rights organizations and international legal scholars that Israel is indeed violating the Genocide Convention. Amnesty International, the world’s leading human rights organization, issued a detailed report in December that found “sufficient basis to conclude that Israel has committed and is continuing to commit genocide against Palestinians in the occupied Gaza Strip.” The following week, Human Rights Watch issued its own detailed report noting that Israel’s “pattern of conduct, coupled with statements suggesting that some Israeli officials wished to destroy Palestinians in Gaza, may amount to the crime of genocide.” That same day, Doctors Without Borders/Medicins Sans Frontieres issued a report confirming many of these findings and called “on states, particularly Israel’s closest allies, to end their unconditional support for Israel and fulfill their obligation to prevent genocide in Gaza.”

This followed reports released in September by the United Nations Special Committee and the office of the United Nations Special Rapporteur citing statements by Israeli officials that imply intent to harm Gaza’s populations, a necessary condition for the legal threshold of genocide to be met. Similarly, in January 2024, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) noted that accusations of genocide were “plausible” and, by a 15-2 vote, enacted “provisional measures” — which are binding under international law — requiring Israel to prevent genocide against Palestinians in Gaza.

There is growing consensus among academic experts as well. For example, the distinguished Israeli historian Omer Bartov, a professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Brown University, concurred that Israel was conducting “a war of annihilation” in the Gaza Strip, noting that the Israeli military “is destroying Gaza.” Similarly, Lee Mordechai, a leading Israeli historian based at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, observed in a comprehensive report on Israeli war crimes in Gaza: “There don’t have to be death camps for it to be considered genocide. It all boils down to the commission of acts and the intent. … What all these acts have in common is the deliberate destruction of a group.”

In the face of this growing consensus of international legal opinion, however, Biden insisted, “What’s happening is not genocide. We reject that.”

In response to the Amnesty International report, a State Department spokesperson insisted that “allegations of genocide are unfounded,” though he acknowledged he hadn’t actually read it. When pressed by reporters about findings that Israel was deliberately targeting civilians, he insisted that the high civilian death toll was actually a result of Hamas allegedly “using civilian facilities as bases and operating centers,” though he failed to cite any examples.

It is important to note that Israel is not the only country that Amnesty International, other nongovernmental organizations and various U.N. agencies have accused of genocide. Nor is it the only case where the U.S. government has rejected such findings.

Genocide is one of those unusual words whose legal definition is actually broader than the popular definition. Legally, it does not just include the attempted systematic extermination of an entire people, such as those of European Jews targeted by Nazi Germany or Tutsis targeted by the Rwandan government, but other acts of violence. The convention states:

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Despite well-documented instances of these acts and other major war crimes by Israel’s government, the Biden administration was steadfast in its opposition to conditioning the massive transfers of U.S. arms to Israel, vetoed a series of otherwise unanimous U.N. Security Council resolutions seeking to end the conflict and roundly criticized human rights groups and international jurists who disagreed.

Similarly, most mainstream U.S. media outlets have refused to acknowledge a genocide is taking place — or even allow others to say so. In early January, The New York Times rejected a paid advertisement by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker nonprofit organization, calling for a ceasefire in Gaza because it included the word “genocide,” proposing it be replaced by the word “war,” which the AFSC noted has an “entirely different meaning both colloquially and under international law.”

But neither the denial by U.S. media outlets nor the Biden and Trump administrations’ defense of Israel’s far-right government in the face of a growing international consensus that it is committing genocide are unprecedented. The U.S. response to Israeli war crimes is neither unique nor unexpected. Since emerging as a global superpower, the United States has repeatedly denied, downplayed and covered up for atrocities committed by allies using American weaponry, blocked efforts to end violence through vetoes at the U.N. and attacked international legal institutions and human rights organizations for seeking accountability under international humanitarian law.

Such policies have obvious moral implications, but they also harm international humanitarian law in general and U.S. credibility in challenging genocidal violence in Darfur, Myanmar and elsewhere. If the United States, which played such a major role in the creation of the Genocide Convention and other foundations of international law, continues to be seen as an accomplice to genocide, it will make it all the more difficult to prevent new genocides in the future.

In 1971, Bangladeshis launched a war of independence against the Pakistani regime of General Yahya Khan, following his rejection of election results that gave the Bengali-dominated opposition a clear victory. During those nine months of fighting, between 500,000 and 3 million civilians were killed by Pakistani forces. Between 200,000 and 400,000 Bangladeshi women were raped. Over 10 million Bangladeshis fled into India.

Despite the genocidal violence, the U.S. government under President Richard Nixon broke a previous arms embargo on Pakistan and encouraged countries receiving U.S. military assistance, like Jordan and Iran (then a U.S. ally), to pass on U.S. armaments to the Pakistani generals. Several American officials in the U.S. consulate in Dhaka raised strenuous objections to Washington’s acquiescence to the genocide, referring to it as “moral bankruptcy,” and the U.S. ambassador to India also called on Nixon to end support for the Pakistani regime. These calls were rejected, and U.S. Consul General Archer Blood, who alerted Washington about the ongoing genocide, was immediately recalled.

According to Time magazine that autumn, “the U.S. has been ostentatiously mild in its public criticism of the atrocities and of Pakistan’s military ruler, President Yahya Khan — a man whom President Nixon likes.” Indeed, Nixon personally told the Pakistani dictator, “I understand the anguish you must have felt in making the difficult decisions you have faced.” In White House tapes that were later released, it was revealed that Nixon believed he could get away with it, noting how a genocidal war by Nigeria against the Christian region of Biafra had “stirred up a few Catholics,” but he didn’t expect such a reaction regarding Bangladesh since “they’re just a bunch of brown goddamn Muslims.”

When India intervened militarily to stop the genocide, George H.W. Bush, then-U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and future president, condemned it as “aggression.” Meanwhile, Nixon dispatched ships from the Seventh Fleet into the Bay of Bengal as a show of support for Pakistan and encouraged China to move troops to the Indian border to increase the pressure.

Small protests led by Quakers and other activists at U.S. ports, where arms were being loaded onto Pakistani freighters, helped galvanize a movement that led Congress to push for an arms embargo which, combined with Indian military intervention, finally put an end to the genocide. But a Cold War mindset, which dictated that supporting even the most nefarious allied regimes was necessary for U.S. national security interests, led Washington to allow genocide if committed by allies. “Above all, Bangladesh’s experience shows the primacy of international security over justice,” as the political scientist Gary J. Bass noted in the journal International Security.

Another genocide in which the United States played a role took place in East Timor. According to the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor, established under the U.N. Transitional Administration in East Timor in 2001, between 102,800 and 183,000 civilians died as a result of Indonesia’s occupation between 1975 and 1999, either murdered outright or starved through prolonged sieges of areas controlled by the resistance. Given that the population of East Timor at that time was only 600,000, this constituted, proportionally, one of the worst genocides in history.

Gen. Suharto’s penchant for mass killing during his reign as Indonesia’s dictator (1967-1998) was no secret. His U.S.-backed military regime murdered between half a million and 1 million leftists, as well as members of the Chinese and Abangan minorities. On Dec. 6, 1975, during a visit to the Indonesian capital of Jakarta, President Gerald Ford gave Suharto the green light for a full-scale invasion of East Timor, which began less than 24 hours later. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger publicly stated that the United States “understands Indonesia’s position on East Timor” — that is, that the newly independent former Portuguese colony not be allowed its right of self-determination under international law. While the U.N. Security Council voted unanimously for Indonesia to halt its invasion and withdraw to its internationally recognized borders, Washington blocked the U.N. from imposing economic sanctions or any other means of enforcing its mandate. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, then-U.S. ambassador to the U.N., later bragged that, under State Department instructions, he had made the U.N. “totally ineffectual” in bringing a halt to the invasion.

In 1977, his first year in office, President Jimmy Carter ordered a 79% increase in military aid to Indonesia, including deliveries of counterinsurgency aircraft that allowed the Indonesians to dramatically expand the air war with devastating consequences. When asked about the U.S. law prohibiting arms transfers to such aggressor nations, a Carter State Department official said that, since Indonesia had annexed East Timor, the conflict was no longer an invasion but an internal rebellion. As Carter’s assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, Richard Holbrooke played a major role in the Carter administration’s pro-Indonesia tilt. He argued that good relations with this large, strategically located, oil-rich, pro-Western nation were vital — even as the military aid package helped make possible wholesale slaughter during this period. He also took part in the Carter administration’s cover-up that followed. In testimony before Congress on Dec. 4, 1979, Holbrooke claimed that the mass starvation of East Timorese civilians was simply due to neglect during Portuguese rule.

The 1991 massacre of 270 unarmed East Timorese protestors by U.S.-armed Indonesian occupation forces led to widespread public outcry and a congressional effort, led by Sen. Russ Feingold of Wisconsin, to condition U.S. arms sales to Indonesia on human rights improvements in East Timor. Stanley Roth, deputy assistant secretary of defense for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, led the Pentagon’s campaign to defeat the Feingold amendment. During the debate, Roth said the U.S. would consider reducing arms sales only if Indonesia staged another massacre. After a stint as senior director for Asia on the National Security Council under the Clinton administration, Roth acknowledged in The Washington Post that the “driving dynamic” of U.S. policy toward Indonesia was Washington’s desire “not to totally screw up the trade relationship” over human rights concerns or Indonesia’s ongoing defiance of the U.N.

After a civil insurrection ousted Suharto in 1999, a referendum in East Timor showed overwhelming support for independence, prompting Indonesian forces to engage in a final spasm of violence. Nearly 70% of the country’s buildings were destroyed and as many as 400,000 people were forced to flee. Thousands were killed. Death squads particularly targeted journalists, human rights activists, U.N. workers, supporters of independence and Catholic priests and nuns. President Clinton initially rejected calls for military intervention to end the slaughter, and even suggestions that the U.S. could threaten to end military cooperation with the Indonesian military, cut off further international loans or simply freeze the extensive overseas assets of Indonesia’s generals, which probably would have ended the assaults earlier. After nine days of terror, growing international pressure finally convinced Clinton and other world leaders to dispatch international peacekeeping forces, led by Australia, thereby eventually ushering East Timor to independence.

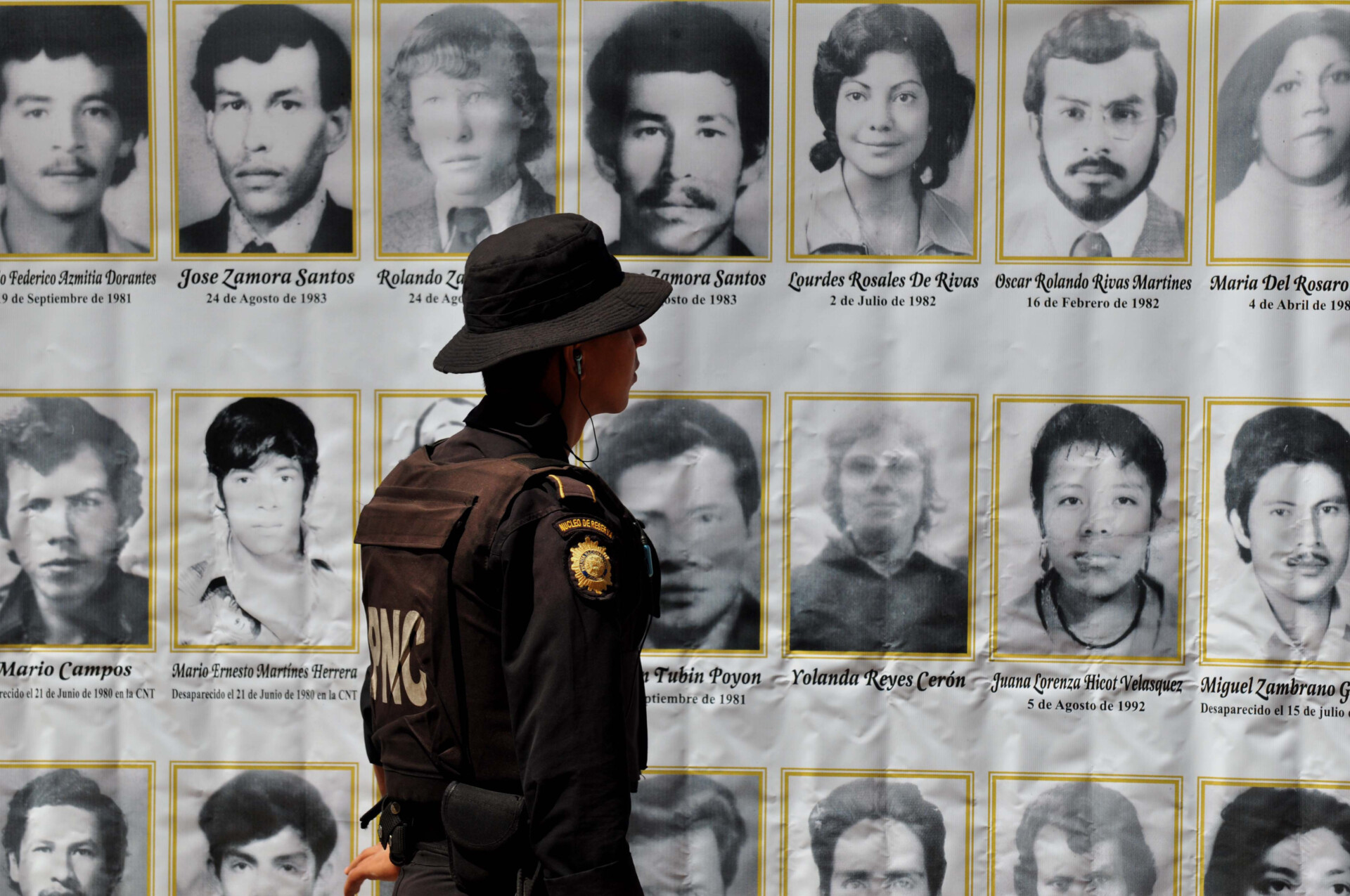

The modern genocide closest to home for the United States was in Guatemala. The Guatemalan Commission for Historical Clarification estimates that during the country’s civil war (1960-1996) there were approximately 200,000 deaths and disappearances, the vast majority of them civilians. Over 80% of the casualties, primarily Indigenous civilians in the highlands, took place between 1981 and 1983. The worst of the killing happened under the rule of Gen. Efrain Rios Montt, with a minimum of 100,000 Mayan peasants executed during this period. According to the Shoah Foundation at the University of Southern California, the Guatemalan military, supplemented by death squads hired by wealthy landowners, “systematically razed more than 400 villages, torching buildings and crops, slaughtering livestock, poisoning water supplies, and killing or abducting whomever they pleased. People who were snatched off the street or dragged out of their homes were often summarily executed and dumped in unmarked graves.” According to the United Nations, an estimated 100,000 Mayan women were raped. Up to 1.5 million people were displaced — more than one-fifth of the country’s population — and 200,000 fled the country.

U.S. military and intelligence units had worked closely with the Guatemalan army since the United States engineered a military coup that ousted Guatemala’s democratically elected reformist president Jacobo Arbenz in 1954. The Carter administration suspended direct military aid to Guatemala over widespread human rights abuses, but it was restored soon after Ronald Reagan came to office in January 1981. As he had done before when defending unconditional military aid to other dubious allies, Reagan dismissed reports from human rights groups of the ongoing genocide, insisting that Rios Montt was being given a “bum rap” and was actually “a man of great personal integrity.”

Reagan’s assistant secretary of state for human rights made the Orwellian claims that Rios Montt’s rule had “brought considerable progress” on human rights, that “the amount of killing of innocent civilians is being reduced step by step” and that “that kind of progress needs to be rewarded and encouraged.” Embassy officials “trekked up to the scene of massacres and reported back the army’s line that the guerrillas were doing the killing,” The New York Times reported.

The Reagan administration, in its obsessive belief that every leftist uprising in the hemisphere was part of a Soviet effort at global conquest, was willing to go to almost any lengths to deny that a genocide was taking place.

Rios Montt was overthrown in a coup in 1983. Repression continued, albeit at a lesser pace, until a peace treaty ended the civil war in 1996. In 2013, a Guatemalan court convicted Rios Montt of genocide.

In multiple cases involving clear violations of the Genocide Convention, the U.S. government denied that genocide was actually taking place, tried to blame the victims on the receiving end of the violence and attacked human rights groups and international organizations that documented the war crimes. As a result of these actions, Washington enabled these genocides — or at least made them worse.

Biden continued this sordid tradition in his defense of Israel’s war on Palestinians in Gaza, and the new Trump administration, which is already scaling back offices in the State Department and Defense Department concerned with promoting human rights and minimizing war crimes, will likely be even worse. Trump’s call to forcibly remove Palestinians from Gaza, “level” the remaining structures, place the territory under U.S. control and bring in settlers to create a major resort area is an indication of how little regard he and his administration have for international law.

Yet history shows that administrations of both parties prior to Trump — notwithstanding their idealistic rhetoric about freedom, human rights and the rule of law — have been mostly guided by narrow geopolitical calculations, even when presented with evidence of genocide.

Despite what Biden, Trump and other supporters of the Israeli government might allege, the ICJ decision to investigate charges of genocide against Israel is a function not of the court’s bias, but of the simple fact that no country has bothered to petition for charges against, say, Turkey or Saudi Arabia. There have been other cases (in which the United States was not involved) filed before the ICJ, such as Gambia’s motion to investigate genocide against the Rohingya by the Myanmar regime (which the court has adopted) and Russia’s charges of genocide against Russian-speakers by the Ukrainian government (which the court rejected).

In many respects, U.S. support for Israel’s genocide against the Palestinians in Gaza is even less forgivable than these earlier cases, since the extent of the killing is so well-known. Rather than being relegated to the back pages of major newspapers, as some of these other tragedies were, on-screen images of the Gaza genocide have been readily available to Americans.

This is the first genocidal war in which young activists are seeing the United States play a major part. Given that the U.S. role in these previous conflicts got neither the attention it deserved at the time nor sufficient prominence in the historical record, many young activists and others assume that this is a unique event, that Israel is uniquely evil and that the United States is somehow reluctantly being dragged along as an accomplice due to an all-powerful “Zionist lobby.”

But it’s critical to recognize that U.S. support for genocide is not new or unique. It is, in fact, a tragically familiar pattern in which the perceived strategic and economic imperatives of America’s national security managers obscure U.S. support for war crimes — and even complicity in genocide. Exaggerations of “Zionist power” divert attention from those who actually make the policy decisions. Those of us who seek to end U.S. complicity in atrocities must recognize that the problem is far deeper.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.