In November 2016, in an op-ed in the New York Times, 92-year-old Jimmy Carter implored then-President Barack Obama that he “must” take a “vital step” before his term expired and “grant American diplomatic recognition to the state of Palestine.” With urgency, Carter expressed his conviction that “the United States can still shape the future of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict before a change in presidents, but time is very short. … I fear for the spirit of Camp David,” Carter wrote. “We must not squander this chance.”

Carter wrote this open letter to Obama not only as the president who had orchestrated the 1978 Camp David Accords but as a man for whom “the primary foreign policy goal of my life has been to help bring peace to Israel and its neighbors.” Most of all, what threatened that goal, Carter wrote, was that, “38 years after Camp David,” Israel was “building more and more settlements, displacing Palestinians and entrenching its occupation of Palestinian lands.”

It is striking that, aside from the “38 years after,” Carter might well have written those same words of advice to himself in 1979 or 1980 (except promising to support merely the idea of Palestinian statehood), although he would not have heeded them at that time. Perhaps even more discomfiting for Carter would have been acknowledging in 2016 that the Camp David framework might have contributed to the expansion of Israeli settlements, the continual absence of Palestinian political sovereignty and a history quite at odds with a “just and lasting peace in the Middle East.”

When Carter arrived in the White House in January 1977, his priority in the Middle East was to help broker a comprehensive peace settlement between Israel and its neighbors Egypt, Syria and Jordan. Consistent with what had been U.S. policy before his presidency, Carter hoped to structure a settlement around U.N. Security Council Resolutions 242 (1967) and 338 (1973), which meant both Israeli withdrawal from “occupied territories” in the Sinai, Gaza, the Golan Heights and the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and each state’s full recognition of the other’s political independence and right to secure, recognized borders.

Carter, unlike his predecessors in the White House, had publicly acknowledged Palestinian national aspirations and indicated his support for a Palestinian “homeland.” The plight of Palestinians represented for Carter the most transparent human rights issue in the Middle East, and he had promised to make human rights a priority for U.S. foreign policy. He intended to include representatives of the Palestinian people in the negotiations as well as representatives from the Soviet Union, Syria and Jordan to ensure that all parties were at the table. He expected that Washington’s strong relations with the Shah of Iran would be helpful to ensuring the peace deal, not least because the monarch could help offset any loss of Israeli oil in the Sinai with shipments from the Persian Gulf.

Yet the main action was expected to take place not in the Persian Gulf but among Israel and its neighbors. If a comprehensive peace along these lines could be achieved, Carter thought, not only would it alleviate the prospect of future war in the region, but it would greatly serve U.S. strategic interests. As Secretary of State Cyrus Vance put it, the “critical importance of stable, moderate, pro-Western regimes in the Middle East and access to Arab oil meant that a return to a passive U.S. posture [in resolving the Arab-Israeli conflict] was not realistic.”

Things did not go according to plan. First, Israeli elections in 1977 swept the far-right Menachem Begin into power; he had long insisted publicly on Israel’s biblical right to “Judea and Samaria” — that is, all the occupied territories to Israel’s east and more. Then Egyptian President Anwar Sadat unilaterally accepted an invitation to go to Jerusalem to declare to Begin and the Israeli Knesset his desire for peace, thereby undercutting the positions of other Arab interlocutors. By recognizing Israel while it still occupied Arab lands, Sadat elicited widespread anger in the Arab world.

Arab indignation over Sadat’s overture, combined with Begin’s intransigence over the occupied territories, convinced Carter and Vance that they weren’t going to get the peace they sought. Although he was disappointed, Carter forged ahead in trying to cobble together a U.S.-brokered settlement with Begin and Sadat. The other Arab actors (not to mention the Soviet Union), having been cut out, opposed the process and decided that U.S. leadership was not even-handed. Meanwhile, the shah — who, despite Carter’s awareness of his regime’s human-rights violations, continued to receive the U.S. president’s full support — began to face turmoil on the domestic front. Not least among the grievances of his opponents at home was the shah’s apparent subservience to U.S. and Israeli interests, a view that the dissident cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had turned into a rallying cry from his exile in Iraq.

By 1980, the comprehensive portion of the peace settlement had permanently stalled. Begin’s government continued to expand Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. The shah’s government had fallen and had been replaced by one led by Khomeini, and Americans in Iran were suddenly targeted. The Soviet Union (as some Carter officials had hoped) invaded Afghanistan. Carter’s plans for the region were in shambles and, accordingly, his prospects for reelection had plummeted.

It was under these conditions that, in January 1980, in his State of the Union address, Carter announced the principle that the U.S. would look on any threat in the Persian Gulf as inimical to “vital interests” and thus would use all means, including military force, to defend the area. This principle was dubbed the “Carter doctrine.” The historian Andrew Bacevich has called its promulgation the inauguration of “America’s war for the greater Middle East,” which has led to U.S. interventions in Lebanon, Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. So, while Carter began his presidency with a vision for a just and lasting peace in the Middle East, he ended it by inaugurating a decadeslong war across the region.

Here we must ask: What role did Carter himself play in the unraveling of his plans for the Middle East? A tempting explanation would be to see the events that led to Carter’s bellicose stance in 1980 as totally unexpected and outside his control, not to mention unrelated to his other efforts in the region. But this would miss the bigger picture. Carter’s Middle East strategy unraveled in part because the range of characters he interacted with and whose own political perspectives he took seriously was far too limited. The pull of vocabularies and policies associated with Henry Kissinger proved to be stronger than Carter’s stated desire to break free of them. At the same time, the discord between Carter’s general interest in human rights and his unsustained attention to the rights that many people in the region cared about most became a strategic liability.

From the start, those shortcomings compromised Carter’s decision to place the U.S. at the center of Middle Eastern affairs. His choices alienated potential partners of the U.S., polarized regional politics and ultimately led Carter to accept the militarization of U.S. policy in the Middle East. The more embattled his policies became, the more inclined Carter was to support practically anyone who opposed nationalism, radicalism and popular movements in the region. After his presidency, Carter was often willing to engage with the political desires and ideas of a wider range of regional actors than he did while president (or that the administrations following his did). As we reflect on Carter’s remarkable life and legacy, we should ponder why he spent a good deal of the four decades after his presidency trying to reconcile himself with the unraveling of his hopes for the Middle East.

During his unlikely run for the White House after his tenure as Georgia’s governor, Jimmy Carter sought to distinguish himself from the seemingly amoral stratagems and deceptions of the Nixon and Ford years at which Kissinger excelled. As Carter put it in his book “Why Not the Best?” — his campaign autobiography — “A nation’s domestic and foreign policies should be derived from the same standards of ethics, honesty, and morality which are characteristic of the individual citizens of the nation.” Carter promised a leadership that derived “from the fact that we try to be right and honest and truthful and decent.” But to the degree that this meant being the anti-Kissinger, this was going to be especially difficult in the Middle East.

Kissinger had loomed large over U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East for the previous seven years, as national security adviser and secretary of state under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. He, more than anyone else, had set the rules for how the U.S. conducted diplomacy in the region and with whom it did business. As with any new administration that promises to chart a new course, there were difficult choices for Carter to make about how far to deviate. Kissinger’s frameworks and promises, as well as his body of work in the region, constrained Carter more than he expected they would.

Carter’s desire to break with the “step-by-step” approach of Kissinger’s ballyhooed shuttle diplomacy after the 1973 war between Israel and Syria and Egypt stalled almost immediately. According to the rules of the game that Kissinger had established after the first meeting of the Geneva Conference in 1973, the Soviet Union was to be sidelined, and peace was to develop slowly, separately and bilaterally. But as Zbigniew Brzezinski put it in “Power and Principle,” his memoir of his years as Carter’s national security adviser, “there were simply no more ‘small steps’ to be taken.” Carter therefore included the Soviet Union in his plans and the joint U.S.-Soviet framework for the conference emphasized a comprehensive agreement.

The 1977 publication of the U.S.-Soviet statement announcing these principles elicited fierce public criticism in the United States from cold warriors and anger from American Jewish organizations, which suspected Carter of tilting away from Israel. The hostility of the reaction surprised Carter, who saw the statement as simply a procedural preliminary. With Carter on the defensive, Sadat seized the opportunity. Having long been a participant in the process, Sadat understood the rules of the game better than Carter did. He dealt a fatal blow to Carter’s plans for Geneva by unilaterally declaring his willingness to go to Jerusalem without prior conditions. Sadat’s motivations for undermining the Geneva Conference were complex. In any case, his move forced Carter to choose between embracing the “step-by-step” approach of a separate peace between Egypt and Israel and having his hopes evaporate for any Middle East peace deal at all.

Even more damaging to Carter’s plans were the constraints that Kissinger had placed on the U.S. relationship with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which was then based in Lebanon. As the PLO’s status as the sole representative of the Palestinian people became widely accepted internationally, Kissinger (in letters written by him and signed by Ford) had promised Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin that the U.S. would not recognize or negotiate with the organization until it had officially recognized Israel’s “right to exist” and renounced terrorism. The stipulation of recognizing the Jewish state’s right to exist had raised the bar beyond U.N. Resolution 242’s provisions, and it existed nowhere in international law. It essentially insisted that the PLO must agree to the legitimacy of Palestinian dispossession as a condition simply for being able to talk with the U.S. Even for PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, who wanted relations with the U.S., this would be a tough sell within his organization’s Central Committee.

When Carter became president in 1977, he faced a choice: Would he impose the conditions of Kissinger’s promise to Rabin on his own administration, or would he shift directions, given that some in the PLO had indicated a desire for diplomacy in the direction of a two-state solution? Carter, Vance and Brzezinski wanted to include the PLO in the ill-fated Geneva Conference but decided to stick to Kissinger’s playbook. “It was our feeling that we had to respect that promise,” Brzezinski later wrote in “Power and Principle.” The administration thereby undercut its ability to open a meaningful dialogue with the PLO. In fact, as one of Carter’s advisers wrote in defense of Carter during his 1980 reelection campaign, “It was President Carter who took the Ford-Kissinger pledge not to negotiate with or recognize the PLO and extended it to bar contact between U.S. officials and the PLO while the PLO does not accept Israel’s right to exist free from terrorism.”

Perhaps more insidious was the modus operandi of U.S. relations with the Shah of Iran, again as established by Kissinger. According to the Nixon doctrine, Washington assigned the shah as one of the “cops on the beat” in the Middle East. The shah was thereby largely responsible for ensuring the preservation of U.S. interests in the Persian Gulf. “Protect me,” Nixon had told the shah during a 1972 meeting in Tehran. In accordance with this protection, the Nixon administration naturally increased the sale of U.S. arms to Iran, and the flow of military aid and weapons did not slow during the 1970s. According to Gary Sick, the Iran specialist on Carter’s National Security Council, Kissinger cleared the bureaucratic pathways so that whatever the shah asked for in terms of weapons would be approved in short order.

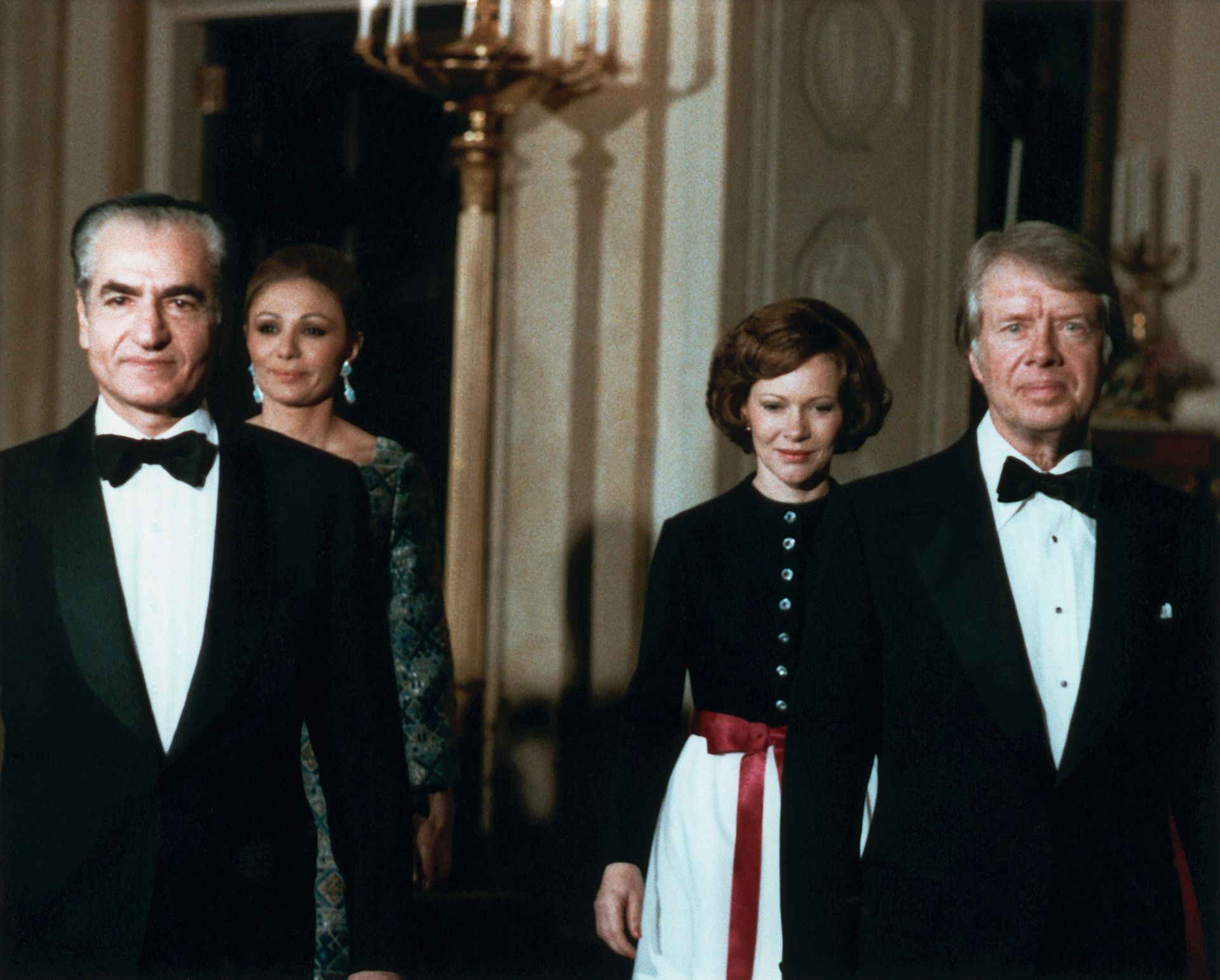

Upon first meeting the shah, Carter indicated his awareness of human rights abuses in Iran and urged the monarch to consider reforms. But the administration took no concrete steps beyond verbal encouragement. In December 1977, channeling Kissingerian realpolitik, Carter uttered what would become one of the more ignominious phrases in U.S. diplomatic history, when he referred to the shah’s Iran as “an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world.” Also like Kissinger, Carter saw the shah as virtually synonymous with Iran, paying almost no attention to other elements in the country. He and the first lady, Rosalynn Carter, developed friendly relations with the Iranian monarch and his wife, Farah. They toasted each other. The dynamic established by Kissinger persisted through Carter’s term until it no longer could be sustained, and Carter presided over the irrevocable deterioration in U.S.-Iranian relations.

Although Carter’s choices in the Middle East were constrained by the frameworks, operating procedures and relationships that Kissinger established in the region, he nonetheless had choices. While he wanted to distinguish his foreign policy from that of the preceding era by reorienting it toward a concern for human rights, in critical cases Carter chose mostly to work within Kissinger’s frameworks rather than outside them. He calculated that the costs of radically breaking from Kissinger’s operating procedures would be too high, not least for his reelection chances. In the end, though, these choices undermined both his aims of achieving a comprehensive peace and of achieving regional stability.

In the summer of 1978, Carter invited Sadat and Begin to the presidential retreat of Camp David in the Maryland mountains for prolonged informal discussions over a Middle East peace agreement. Both Sadat and Begin accepted Carter’s invitation without delay. From Sept. 4 to 17, Carter and his foreign policy team, along with delegations from Egypt and Israel, haggled over the architecture for a peace treaty between the two nations. Both sides agreed to the framework, pending ratification by their parliaments. Further, they agreed that bilateral peace was to be the first step in a broader peace between Israel and its neighbors according to the principles of U.N. Resolutions 242 and 338. Many chose to believe that the intractable Arab-Israeli conflict and the related “question of Palestine” were, at long last, under Carter’s careful and informed mediation, on the way to resolution.

“There is only one nation in the world which is capable of true leadership among the community of nations,” Carter wrote before becoming president, “and that is the United States of America.” More than any president before him, Carter put the U.S. at the center of the quest for a “just and lasting peace in the Middle East,” as articulated in U.N. Resolution 242. He believed that the U.S. had the requisite power and moral authority to resolve disputes in the Middle East and to guarantee peace. This aspiration squared with Carter’s broader sense of mission. In addition to being a former peanut farmer and governor of Georgia, Carter had been a Sunday school teacher. He landed in the White House asking rhetorically what might be achieved if the U.S. did its “best” in the world. He promised a U.S. foreign policy rooted in principle and American civic values.

As the holy land — the site where Abraham and Jesus had been born, lived and died — the Middle East had an emotional pull on the devout Southern Baptist Carter. In line with God’s work, Carter believed that the U.S. was uniquely positioned to bring historically warring regional actors (who could be reminded that they worshiped the same God) together for the broader interest. Yet many regional actors and others throughout the Global South (or Third World, in the parlance of the day) would find Carter’s version of Middle East peace to be skewed, unjust and likely to sow conflict more than to resolve it. As it turned out, Carter’s placement of the U.S. at the center of the peace process exacerbated American isolation in the region and in international forums.

To be sure, the Camp David Accords did bear a distinctly American imprint. By the mid-1970s, U.S. political culture was further out of step with the political and social views of much of the Middle East — and of the rest of the world — than it had been in the 1960s. Centering the U.S. in the peace process meant that an American understanding of the underlying problems in the Middle East rooted in 1970s U.S. political culture would be formative in how the conflict would be resolved. For instance, despite his initial acknowledgment of Palestinian interests, Carter’s framework for the Middle East suggested by its design that history and grievances and strong emotions need not be obstacles to peace, as long as the U.S. was at the center.

His combination of public optimism and the desire to overcome — even erase — troubling histories was in line with the American political and cultural ethos of the late 1970s, which also sought to forget the traumas of the Vietnam era. Carter had been elected as an outsider in 1976, partly because he was untainted by Vietnam and partly because he promised to break away from the past while not holding the U.S. responsible for what had happened in Southeast Asia. This fantasy of overcoming traumatic history was captured in the triumphant vision of Carter bicycling back and forth between Begin’s and Sadat’s encampments at Camp David and gradually softening the incompatibility of their positions toward an agreement.

Not only did American political culture inform Carter’s vision for peace, but now the twists and turns in U.S. domestic politics would have greater ramifications for the fate of the peace process and broader developments in the Middle East. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Carter’s inability to forcefully oppose the building of new Israeli settlements in the occupied territories while the peace negotiations were developing. Privately, Carter, Brzezinski and Vance understood that they would have to apply pressure on Begin to budge him from his stance on settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem if they were going to have any chance for a broader peace. They had hoped that American Jewish organizations would be more sympathetic to Carter’s intentions and less unified in supporting Begin’s far-right policies. By 1980, however, administration officials were contorting themselves to avoid upsetting Begin even by merely restating long-standing official U.S. positions on settlements in international forums. After an avalanche of criticism, Carter renounced a U.S. vote for a resolution condemning the building of new settlements on occupied land because the resolution included phrases on settlements in East Jerusalem, the first time any U.S. president had retroactively renounced a Security Council vote made by his administration. Conflicts over what kind of peace Carter could pursue without sabotaging his electoral prospects plagued his presidency. At the same time, these sorts of calculations necessarily isolated the U.S. internationally.

Centering the U.S. in Middle East peace, in fact, meant sidelining the United Nations. While the framework for peace between Israel and its neighbors had been established by the U.N. Security Council in the aftermath of two previous wars in 1967 and 1973 (by Resolutions 242 and 338, respectively), the politics of decolonization within the U.N. had made it much more suspect from an Israeli point of view. In 1974, the U.N. General Assembly had recognized the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, as had many other nations. In 1975, the U.N. General Assembly passed a resolution equating Zionism with racism and racial discrimination, a move that would have long-term reverberations. The growing international legitimacy of the PLO and the consistent lumping of Israel with “colonial and racist regimes” alienated Israel in the international community.

Given this situation, Carter wagered that the U.S. could play the critical facilitating role in brokering peace. But this claim also meant that the U.S. could be held mostly responsible for that peace’s injustices, failures and violent consequences. In this way, Camp David sharpened the isolation of the U.S. in the Middle East. Even “moderate” Arab regimes that historically enjoyed tight relationships with Washington, like Saudi Arabia and Jordan, could not afford to support Camp David publicly. Arab summits in Baghdad in 1978 and 1979, despite private promises to the contrary, became stages for embarrassing, humiliating and shaming those Arabs who participated in Carter’s peace process. And this shaming extended beyond the Arab world. In international forums such as the U.N. Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Women’s Plan in Copenhagen and the General Assembly and Security Council, anger against Israel and the U.S. intensified.

In effect, Carter permanently hitched the U.S. — and his own legacy — to an idiosyncratic vision of “peace in the Middle East” that was deeply flawed and highly unpopular. Some of the unfortunate consequences of this reality were apparent soon enough to Carter himself. In his final meeting with Israel’s ambassador to the U.S. in January 1981, Carter observed that “Begin showed courage in giving up the Sinai. He did it to keep the West Bank.” After being “retired” from public office (as he put it) by the 1980 election, Carter continued to visit the Middle East and to work with the interlocutors that he had cultivated during his presidency. In 1983, Carter paid a visit to Syrian President Hafez al-Assad in Damascus. As Carter described it, the two had a heated exchange about the consequences of the Egyptian-Israeli peace for the Palestinians, for Lebanon and for the region. One of those consequences, Assad declared, was that whereas Israel had formerly been the principal enemy of Syria, that distinction now belonged to the U.S.

Nevertheless, the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty marked a decisive victory for the U.S. in the Middle East theater of the Cold War. The solidification of the U.S.-Egyptian relationship completed the camp-flip of the Soviet Union’s most important client state in the Arab Middle East during the rule of Sadat’s predecessor, Gamal Abdel Nasser. In this respect, the post-Cold War came early in the Middle East, and Carter oversaw this transformation. One would be tempted to think that Carter might have then relaxed the reflexive U.S. opposition to the forces of social and political change in the region. But that was not the case. If anything, U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East became even more hostile to the winds of change under Carter, as he identified with individuals and leaders who opposed those forces in the region, like Sadat and Begin. In a unique contribution, then, Carter refashioned a Cold War mentality for the post-Cold War landscape. To be sure, Sadat’s and Begin’s credentials as agents of “peace” were more important than their credentials as anti-communists at that moment. But the solidification of military-security alliances embodied in the Camp David process was part of an effort to preclude undesirable or uncontrollable social and political changes in the Middle East.

Sadat’s Egypt and Begin’s Israel joined the shah’s Iran in a structure of bilateral U.S. military alliances in the Middle East that was aimed at protecting American interests and preserving order. Yet that structure was teetering as Camp David was being negotiated, even if the participants did not yet realize it. During the negotiations in September 1978, for example, the shah, besieged by popular demonstrations against his rule, instituted martial law. On Sept. 8, with Washington’s attention focused on Camp David, Iranian forces fired live ammunition at the protesters, killing 58 and injuring more than 1,000. Carter and Sadat both spoke to the shah by phone to express their support. The subsequent collapse of the shah’s regime came as a great shock — not least to Carter’s administration. But it did not lead to a reevaluation of this dependence on the military-alliance structure that had served the shah. Instead, it led to a doubling down on this structure with Sadat and Begin.

In the Arab world, the framing of Camp David set up a natural opposition to manifestations of nationalism, radicalism and popular movements as forces that opposed “peace.” At the same time, Camp David bolstered Iraq’s position in Arab politics, under the emerging leadership of the volatile Saddam Hussein. With Arab League summits in 1978 and 1979 held in Baghdad, Saddam rested his claim to being the true bearer of Arab nationalism on his being the opposite of Sadat, whom Washington had suckered into betraying the Arab nation. At its March 1979 summit, the Arab League issued a communique excoriating Sadat for having “deviated from the Arab ranks” and “chosen, in collusion with the United States, to stand by the side of the Zionist enemy in one trench” while violating the “Arab nations’ rights.”

Likewise, Assad, who had initially favored Carter’s plans for Geneva, became a forceful voice of Arab nationalist opposition to Camp David. In a March 1980 interview with the Algerian newspaper Al-Shab, the Syrian dictator defined the difference between the Arab nationalist conception of peace and Carter’s. “To us, peace means that Arab flags should fly over the liberated territories,” said Assad. “Under the Camp David Accords, peace means that the Israeli flag should be hoisted in an official ceremony in Cairo, while Israel is still occupying Egyptian, Syrian and Palestinian territory and still adamantly denying Palestinian rights.”

This intensity of Arab nationalist sentiment made it difficult for Carter, after Camp David, to find any common ground with most of the region’s leaders.

And it was even more difficult after Camp David for Carter to find common ground with Palestinian nationalists, either in the diaspora or in the occupied territories. Palestinian figures across the ideological spectrum excoriated what they saw as the treachery of Camp David. Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine leader Dr. George Habash publicly promised from his base in Lebanon to oppose Camp David by any means. PLO Chairman Arafat portrayed the Palestinian “autonomy” plan proposed by the accords, which promised Palestinians under Israeli occupation individual rights but not national rights, to be “no more than managing the sewers.”

Even Palestinians in the occupied territories, who presumably stood to benefit the most from “autonomy,” rejected the idea out of hand. For example, Mustafa Abd al-Nabi al-Natshay, the deputy mayor of Hebron, argued in 1981 that autonomy “is a deception utilized in order to impose permanent occupation and would confer permanent legitimacy upon the military occupation. This is something we totally reject.”

In identifying America’s peace with Begin, Carter hitched his wagon to a man intent on subduing these voices, as violently as necessary. By Begin’s design — and as Carter understood — peace in the west (with Egypt) opened opportunities for settlement to the east and violence to the east and north, as would be seen with the bombing of an Iraqi nuclear facility in 1981 and, most emphatically, with Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982. Regional actors knew that Israel conducted its military operations with U.S. weapons and equipment, which had become more available because of the terms of Camp David. In these consequences, we see sources of the antagonism toward U.S. policy in the Middle East that would come to define the post-Cold War period.

With Iran, the Carter administration sought to stave off revolutionary change as long as possible. When that wasn’t possible, the White House sought to roll it back. Thus in January 1979, with the shah deposed and having fled the country, the Carter administration discussed the possibility of a military coup that might reestablish its preferred regime structure. Upon returning to Iran in February, Khomeini decried the efforts by the Carter administration to “desperately” institute some “form of government” that was “equivalent” to the shah. “They must know it is too late,” he boasted.

Better relations between Washington and the PLO might have helped the U.S. with Khomeini. This was an argument that Arafat passed along to U.S. officials: that he and others among the PLO leadership, who were treated like heroes in Iran, had Khomeini’s ear.

Indeed, Arafat did intervene on America’s behalf to help secure the release of 13 American hostages in Iran in late November 1979. In the spring of 1980, Arafat helped the United States retrieve the bodies of eight U.S. servicemen killed in the Desert One operation. Arafat did this because he continued to hold out hope for improved relations with the Carter administration. But by the summer of 1980, Arafat held back on further efforts to obtain the release of the U.S. embassy hostages, apparently believing that candidate Ronald Reagan’s campaign manager, William Casey, had made a deal with the Iranians to hold the hostages until after the election, thereby preventing an “October surprise.” Had Carter’s administration recognized the PLO by then, Arafat would likely not have felt compelled to make this calculation.

At the same time, because Khomeini opposed most facets of U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, the Carter administration sought to delegitimize him. This was done first by seeing him as a tool of the Soviets and later by portraying him as the quintessential state sponsor of international terrorism because of his refusal to force the release of the hostages at the U.S. embassy. The antagonism ran deep enough that even Saddam Hussein, a nemesis of Camp David, by virtue of having gone to war against Iran in September 1980, subsequently improved his relationship with the U.S.

Reflecting on Carter’s presidency in his 1983 memoir “Hard Choices: Critical Years in America’s Foreign Policy,” Vance wrote that “for Carter to adopt an activist, balanced policy [in the Middle East] carried a significant political risk. … He could be seen both at home and in Israel as tilting toward the Arabs and pressuring Israel to make dangerous territorial concessions. … In this, as in many other decisions at the outset of his administration,” Carter’s secretary of state concluded, “Jimmy Carter unflinchingly refused to take the easy course on politically sensitive foreign policy matters.”

But Carter could have taken many more risks in opening dialogue with a wider range of popular actors in the Middle East. Additionally, he could have applied more pressure on Begin’s government to support U.N. Resolution 242, which he demanded of all other parties. He might have let go of the Cold War imperative to control Persian Gulf oil. He still would have lost the 1980 election, perhaps even more roundly than he did. But his legacy in the Middle East would have been much more in line with the principles he espoused when he came into office and with those he continually advocated after leaving the White House.

Were America’s isolation in the Middle East and the subsequent militarization of U.S. foreign policy in the region natural consequences of a way of thinking about “peace” and “moderation” as merely the absence of political change? Yes. In the decades of his post-presidency, Carter came to understand that the persistence of Israeli settlements and of the Israeli war against Palestinian statehood (which the peace between Israel and Egypt had done nothing to ameliorate and probably even encouraged) had, above all, doomed the broader peace that Carter had hoped for.

With this realization, we can observe in Carter’s message to Obama a subtle reversal. Now, it was Carter who called on Obama to join the rest of the world on questions of peace and justice in the Middle East: to give the lead back to the United Nations and to recognize Palestine as a state — meaning to more or less treat Palestinians as equal partners. In the 21st century, Carter spoke the language of “peace and justice” rather than simply “a just peace.” Obama, whatever he might have believed, chose not to heed Carter’s advice. Tragically, Obama’s choice may have been more in line with the “spirit of Camp David” than what the nonagenarian Carter advocated.

Indeed, the spirit of Camp David may have been best manifested not in America’s recognition of a Palestinian state but in the 2019 Abraham Accords coordinated by President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, which — like the Camp David Accords — left the Palestinians out.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not represent those of the U.S. Naval War College, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.