One summer morning in Melilla, the Spanish enclave in North Africa, I climbed the steep path into the old fort and up to the battlements. The sea was still, and the heat was yet to settle. There was a sleeping migrant, a child, in a grubby orange armchair outside the city’s general archive, where I had come to meet the historian Vicente Moga.

One hundred years ago, Moga told me, the scene here was very different.

In the days following the Battle of Annual on July 22, 1921, what remained of Spain’s colonial army staggered back into Melilla. Vultures flew in the opposite direction.

“Imagine,” said Moga. “The first officers start arriving by car, and they had taken off their stripes so they wouldn’t be killed [by sharpshooters]. They start spreading the news: This general has died, that colonel has disappeared. The word is panic. … People came up here, to the fort, with something to sleep on, hoping to board a ship and escape.”

Meanwhile in the Rif, Abd el-Krim, the leader who had united its tribes against the Spanish, was trying to keep order after a victory so swift that his troops were upon Melilla. More than 10,000 Spanish soldiers lay dead on the path from Annual.

There is some debate over what happened next.

One view is that, even before Spanish reinforcements began to arrive by boat on the 24th, Abd el-Krim recognized that he could not storm Melilla. It was fortified, and it had soldiers, artillery and ammunition. An assault would be costly.

But Moga disagrees. “Melilla was absolutely abandoned. There was barely a garrison. If [Abd el-Krim] had wanted to, it would have been a military parade … he would have encountered no kind of resistance.”

I asked what stopped him. “In that moment, Abd el-Krim was thinking about the creation of a republic,” said Moga. “And he was thinking about the image it would give that republic if it was born in the massacre of a mostly civilian population.”

The Battle of Annual was among the greatest defeats for a colonial army in Africa. It made Abd el-Krim an anti-imperial icon; his guerrilla tactics were cited by Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh. In 1925, he would be Time magazine’s person of the year.

Yet the centenary of the Battle of Annual has been a muted affair. In Melilla, Vicente Moga helped put on a photographic exhibition. A few new books came out, including one in Spanish, “The Flight of the Vultures,” that used oral sources to tell more of the Riffian side of the story. But in Morocco itself, the commemoration has been quiet.

For the regime, the Battle of Annual and the events it unleashed are a complicated subject. Because when Abd el-Krim founded his republic, he wasn’t just declaring independence from Spain: He was declaring independence from Morocco.

The Republic of the Rif, which was founded in 1923 and held out until 1926, remains the only Amazigh state to have ever existed.

The Amazigh peoples—also known as Berbers, though it’s a term some consider pejorative—are spread across North Africa. Population surveys are patchy, but estimates of their number range from 20 to 40 million. In Morocco, Tamazight, the Amazigh language, is spoken by perhaps 40% of the population. Another large population exists in Algeria, and smaller ones are found in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Mali, Niger and Mauritania. They trace their roots to before the Arab-Muslim conquest in the 7th century.

Precolonial Morocco could be crudely divided into the plains, which the state governed closely, and the mountains, such as the Rif, which it did not. These corresponded to the Arab and Amazigh regions. The Sultan of Morocco was not devoid of power in the Rif—he did, for example, appoint governors in the region—but the Rif’s tribes mostly governed themselves. They paid taxes, if a little irregularly.

According to C.R. Pennell, a historian of the region, the Rif’s autonomy served both sides. The sultan was spared the expense of direct rule while maintaining his sovereignty and a certain level of order and taxation. Meanwhile the Riffian tribes could call on the sultan for mediation in disputes and for the legitimization of local leaders.

The French and the Spanish complicated this arrangement when they split Morocco into two protectorates in 1912. Nominally, the sultan remained in charge throughout the country. But the colonial authorities held the real power, and in the Rif the Spanish went about co-opting the local elites. This meant getting as many of them onto the colonial payroll as possible. In some cases, it also meant taking the sons of tribal leaders and educating them in Spanish cities, as kind of privileged hostages.

Abd el-Krim was one of them. He came from the Ait Waryaghal, the largest tribe in the Rif, and lived in Melilla for over 10 years as a teacher, journalist and eventually secretary-interpreter in the Central Office of Indigenous Matters. He was highly valued by the administration and by all accounts fond of life in Melilla. At one time, he and his father even applied for Spanish nationality, though they received no response.

The relationship between the Ait Waryaghal and the Spanish began to sour during the First World War. Spain was neutral, yet Abd el-Krim was known, in part through his journalism, to be critical of French colonialism. Moreover, his father was quietly supporting German agents in the Rif. In September 1915, the Spanish authorities put Abd el-Krim in prison.

A little under a year later he was released. He left Melilla and rejoined his father in Ajdir, deep in the Rif. They summoned his younger brother back from Madrid. By 1920, the family had effectively severed ties with the Spanish and were organizing resistance. When his father died suddenly that year, Abd el-Krim took control.

The leadup to the Battle of Annual was complex, but under Gen. Manuel Fernández Silvestre the Spanish were encroaching ever further into the central Rif. This aggravated the tribes and overstretched the colonial army. Then particular events, such as the Spanish unprovoked bombardment in April 1921 of a market in Boukidan, a town near Ajdir, stirred fury. (“I call it the Riffian Guernica,” said Moga.) There was an opportunity to unite the fissiparous tribes. Abd el-Krim took it.

After the victory at Annual, Abd el-Krim fought Spain to a stalemate. In 1923, the Republic of the Rif was formally founded. It sought recognition from the League of Nations and found pockets of international support. In France, the left agitated for the Riffian cause. In Britain, a committee of support was set up to lobby the government to recognize the Riffian state. Indian Muslims sent donations.

Meanwhile, Abd el-Krim’s government grew the apparatus of a state. It established a centralized bureaucracy and built roads, a telephone system and a network of military command posts. It created a standing army in which deserters from the Regulars, the mostly Riffian troops in the Spanish colonial army, played an important role. It created its own currency, the Riffiya, which was printed but never went into circulation. And it adopted a flag. The green crescent moon was a clear religious statement.

There were some attempts to establish education and health services, but they were ultimately curtailed by a lack of trained personnel and, most of all, the ongoing war, which consumed everything. “Abd el-Krim didn’t have time to really build the foundations of the republic,” said Moga. “If he’d won the war, he might have had the chance.”

But the war was lost the moment Abd el-Krim attacked the French, drawing them into the conflict. By 1926, the combined Spanish and French armies assembled against the Republic of the Rif exceeded 250,000 troops.

Abd el-Krim surrendered and was exiled to La Reunión, the French island off Madagascar. (Twenty-one years later, while being transported to France, he escaped to Cairo.) The Rif dissolved into its traditional tribal arrangement. Spain reestablished control in the protectorate, which lasted until Moroccan independence in 1956.

“On an official level Morocco has done nothing to commemorate the centenary” of the Battle of Annual, Rachid Raha, president of the Amazigh World Assembly, told New Lines over the phone from Rabat. “And this was one of the great battles of the 20th century, where a bunch of farmers defeated a colonial power.”

Being the centenary, this silence has been more pronounced, but it was not exceptional. The official discourse has never been full-throated in its celebration of the Battle of Annual. And when it does mention it, its version of events is a selective one. The battle is recast as a stepping stone on the path to Moroccan independence. Abd el-Krim, rehabilitated after his death in 1963, enters the pantheon of national heroes as a Moroccan nationalist. The Republic of the Rif is glided over.

“Officially, they only talk about the battles against the Spanish and French armies. They don’t talk about what Abd el-Krim did in society,” said Omar Lmellam, president of the Association for Memory in the Rif, on the phone from Al Hoceima. “In the time of Abd el-Krim, the tribes were united into a confederation to advance our future. For us, Abd el-Krim is a symbol. He wasn’t just a guerrilla, but a symbol of the unification of Riffian society.”

This symbolism might not be so sensitive for the regime if the Rif War had been a one-off event, distant from contemporary politics. But it wasn’t the last time the region rose up. During post-Moroccan independence, there have been cycles of revolts and repression in the Rif.

None of these uprisings was separatist. In general, they sought greater political representation and made economic, social and cultural demands. In 1958, they also petitioned for Abd el-Krim’s return from exile. The regime responded with force.

Iqabbaren, which translates as “burying,” is how Riffians describe the repression of the rebellion of 1958-59. Led by Crown Prince Hassan, the army brought collective punishment against the region, which suffered crop burning, rape, forced disappearances, torture and mass executions. Abd el-Krim’s tribe was singled out. The regime made an example of the Rif at a time when other Arab monarchies were falling.

In 1984, the “hunger riots” in the Rif were met with more violence. Official sources reported 29 deaths. Others claimed 200 deaths and 14,000 detainees. Witness accounts reported burials at night in secret mass graves. In a televised speech at the time, Hassan II made sinister reference to his repression of the Rif in 1958-59: “The people of the north knew me as a crown prince; it is best for them not to know me as Hassan II.”

These were the “years of lead”—not just in the Rif but across Morocco. For more than four decades, detention, torture, mass killings and forced disappearances stifled voices of opposition: the communists and the Islamists; the Amazighs and the Sahrawis; the artists, the intellectuals and the feminists.

For a long time, this history was hidden. That began to change in 2004, when the son of Hassan II and new king, Mohamed VI, initiated Morocco’s truth commission: the Instance Equité et Réconciliation (IER). In the Rif, this was part of a broader shift in policy, from state neglect under Hassan II to a more PR-sensitive project of reconciliation under the new king.

The IER organised seven public audiences throughout the country. The final one took place in Al Hoceima on May 3, 2005, and is described by Najwa Belkziz in her Ph.D. thesis, “The Politics of Memory and Transitional Justice in Morocco.”

Ten victims of state repression gave their testimonies. They had been carefully vetted by the regime. Even so, the terror came through. They described the collective punishments; the poverty and famine that resulted from crop burning; the way the region had been marginalized by the state. They described the exodus since independence of Riffians, forced to find work in Europe.

And they asked the state to relieve the restrictions on memory in the Rif. One speaker, Hakim Benchemmas, said, “I want the state to acknowledge the heroic fight of [Abd el-Krim] against French and Spanish colonialism. It was an experience of freedom, and we have the right to be proud of it. They should let us be proud of it. They should let us teach it to our children in history textbooks.”

On the phone to Rachid Raha, I mentioned that, while in Melilla, I had met a number of young migrants from the Rif who hadn’t known who Abd el-Krim was. “It is not studied in school in Morocco,” he sighed. “There is censorship of Amazigh history. Maybe this can change now. Let’s hope so.”

To this day, there is no official museum in the Rif. There were plans for one in Ajdir, on the site of Abd el-Krim’s headquarters, from where he administered the Republic of the Rif. There were plans for one in Al Hoceima, too. But they remain just plans. “Every year we ask what will become of these buildings,” said Lmellam. “And so far there is nothing.”

Some things have changed under Mohamed VI. The IER gave a limited kind of justice, or at least catharsis. The constitution was revised in 2011 to recognize the Amazigh stake in Moroccan history. Tamazight became an official language. But many of the demands made from the Rif for decades—greater political representation, economic development and the freedom to remember—remain, at most, half-met.

“We wait for the time when a museum will be built that talks about the Republic of the Rif, the flag of the Rif, and all of that. It would be a dream,” said Lmellam. “But we think that if they do build a museum, it will just be a place to put some ceramic objects, some clothes from times long ago and nothing more.”

Under Mohamed VI, there have been two more episodes of unrest in the Rif. The first, in 2011, was part of a national phenomenon at the time of the Arab Spring. The regime headed off the uprising with strategic concessions, including a new constitution. The second, in 2016-17, was centred in Al Hoceima, specific to the region, and perhaps the greatest challenge to the regime since Mohamed VI’s reign began in 1999.

The spark was the October 2016 death of Mouhcine Fikri, a fishmonger whose goods were confiscated by the police. He was crushed to death when he tried to retrieve them from a garbage disposal truck. A protest movement, Hirak al-Shaabi, developed in the following weeks and months. The rallies spread and intensified. Then, in May 2017, the repression began. Hundreds were arrested. Some, including the movement’s leader, Nasser Zefzafi, remain in prison.

Sometimes, while on the phone to people in Morocco, I would ask a question about the Rif. I would word it vaguely so that they could take it where they wanted. The atmosphere would suddenly change, as if a third person had come on the line. Some deflected but maintained the fluency of the conversation. Others simply said: “I can’t talk about that.”

In Spain, I met Reda Benzaza, spokesperson for the Rif’s Hirak movement. “The Rif has become a kind of taboo for people working in human rights in Morocco,” he said. “They can talk about pensions, they can talk about migration, they can talk about anything—but not the Rif. Who in Morocco dares question the palace?”

When the arrests began, Benzaza hid in a safe house. “I spent 28 days there. Imagine: the same clothes; all phones disconnected. In the end I made it out and crossed the border to Melilla. I had Spanish documents, so that wasn’t a problem. The problem was the five police controls between Al Hoceima and Melilla.” He smiled weakly. “The rest of the details I don’t think it’s necessary to tell.”

Many of Benzaza’s companions, now mostly in prison or in exile, cut their teeth as activists in the 2011 protests during the Arab Spring. But their demands echoed those heard in the Rif for decades. “The movement was born of social, economic and cultural demands,” he said. “There is not a single demand that talks about a model of government different from the one that currently exists.”

“But it’s true that it is a movement with a strong sense of identity,” he added. “We identify with symbols that are distinct from those of Morocco. We have our own flag, that of the Republic of the Rif. The portraits we hold up are of Abd el-Krim. The movement is proud of the history of the Rif, of our identity.”

I asked Benzaza about the Battle of Annual. “When you are in Spain it’s a disaster, but for us it’s a glorious time when our grandparents achieved something almost impossible. They did it with arms, whereas our movement identifies as a totally peaceful one, but it is still dear to us. There was an independent state, the Republic of the Rif, 100 years ago. Of course that’s a reference for many of us activists.”

Since 2016, the number of makeshift boats carrying people from Morocco to Spain has increased dramatically. Benzaza volunteers with a group that helps new arrivals and, although the Spanish government’s data doesn’t segment them at a finer grain than their nationality, he claims that most are from the Rif. “There was hope, the possibility of change,” he said. “But when we saw that this was a regime that didn’t provide any alternative, that it was 20 years of prison and torture [for protesting], lots of young people decided to leave it behind.”

Benzaza told me that they came together to commemorate the centenary of the Battle of Annual in the diaspora, where they are truly free to do so. I found the photos online of one such gathering in Barcelona. Few people were present. I asked him about the spirit of those in the movement. “I’d be deceiving you if I said that after four or five years of repression,” he began, then tailed off. “In the end we are people, and we’ve had to leave our lives and start again in different countries. That’s taken a lot of energy, a lot of effort.”

On the phone from Morocco, Rachid Raha and Omar Lmellam had both spoken brightly about the changes in state policy under Mohamed VI. They had their complaints—about the lack of memorialisation, for example, or the little teaching of Tamazight in primary schools—but they also pointed to progress in the Rif.

Benzaza flatly disagrees. “The official discourse has changed. There was a reconciliation in words that never made it as far as reality. The policies remain the same. In that sense, nothing has changed.”

I asked Benzaza whether he felt the regime’s presence here in Spain. He said that Pegasus spyware had been installed on his lawyer’s phone and that he was soon to find out whether it had been installed on his, too. “But of course, we always feel that breath on us. Morocco is among the countries that spends most on espionage and harassment of activists, whether in the country or abroad.” Benzaza caught my eye and looked over at a table near us, where two men were talking with each other. He raised his eyebrows and said no more.

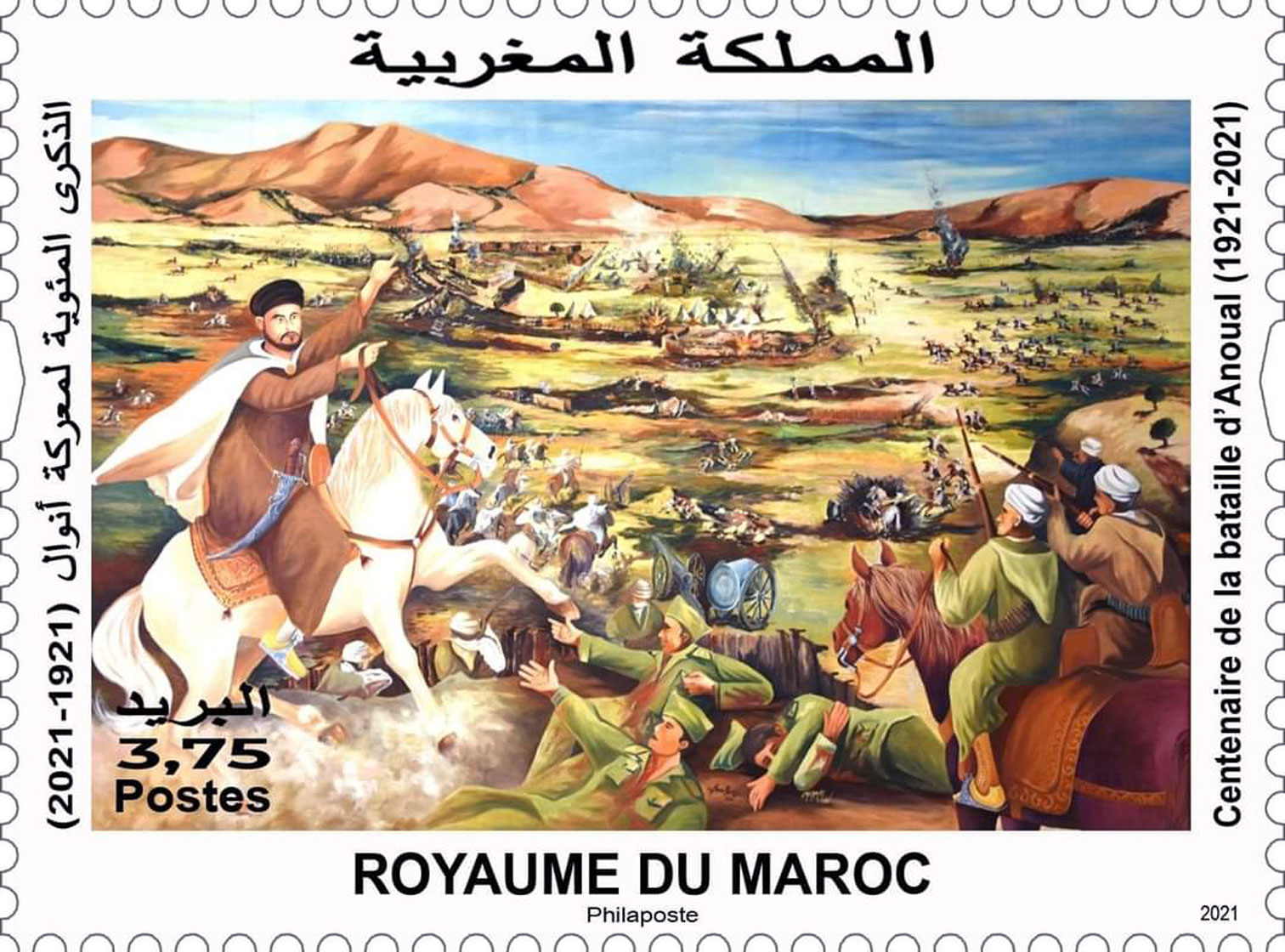

In the weeks after our conversation, Raha continued to send me links on WhatsApp. There were articles about the campaign for reparations from Spain for its use of chemical weapons in the Rif War. There was another about a fund set up by Morocco’s new government to support the official use of Tamazight. And one day Raha sent me a photo: The Moroccan post office had just released a commemorative stamp depicting the Battle of Annual. “Qué alegría,” he wrote. What joy.