Many of us live and die by declarative statements. Some of them are legal, a vital part of the process by which we make political or professional promises. “I do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic,” say U.S. senators. Others are of immense personal importance, seals of integrity made before witnesses communal or divine. “I take thee, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, till death do us part.” Others are less romantic but no less serious. Once German army officers made an oath of allegiance to Hitler in 1933, say historians, their lives were Hitler’s until the bitter end.

For better and worse, our word has somewhat less significance today. If half of first marriages end in divorce in the U.S., fully 73% of third ones fail. While marriage vows are not mandatory in the U.S., statistically speaking, most people who make them are lying. Their real meaning, however, is less to deceive than to utter a strong intention. Perhaps we should be saying, “Under the right circumstances, I really hope to love and cherish you.” Just as I hope to not participate in insurrection against the government, should Homeland Security ask — “Underpromise and overdeliver,” but elevated to an ethos.

Fickle as we are, there’s another kind of declarative statement that takes this truth-bending one step further. It’s also highly intentional but uttered with less good faith. It belongs somewhere between the Bishopric of Bullshit and the Commonwealth of Wishful Thinking, that lonely country where desire and outcome are loath to coincide. Statements that, if you have to say them, aren’t true.

As Dick Cheney told a group of veterans in late 2002: “There is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies and against us.” A few months later, Colin Powell sweetened the pot. “My colleagues,” he told the U.N. Security Council, “every statement I make today is backed up by sources — solid sources. These are not assertions. What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence.” If you have to say it, it isn’t true.

In all fairness, certain Iraqis were guilty of this pleasure, too. As their Minister of Information Muhammad Saeed al-Sahhaf famously said as the smoke of invasion billowed behind him, “There is no presence of American infidels in the city of Baghdad.”

Voltaire may have mocked the Holy Roman Empire as neither holy nor Roman nor an empire, but most of us are guilty of this crime. Think of history’s favorite shibboleths: separate but equal; the war to end all wars; the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea; the Inflation Reduction Act; the Thousand-Year Reich; a land without people for a people without land; happy is he who calls himself a Turk; in Iran we don’t have homosexuals; COVID-19 will be over by Easter; they hate us for our freedoms; we value your privacy; the customer is always right.

Lies, of course, have always been with us, whether social, political or personal. Iconic Israeli historian and author of bestseller “Sapiens” Yuval Hariri says we desperately need them, for they offer up membership into much larger tribes. “Fiction has enabled us not merely to imagine things, but to do so collectively. We can weave common myths such as the biblical creation story … and the nationalist myths of modern states. Such myths give Sapiens the unprecedented ability to cooperate flexibly in large numbers … That’s why Sapiens rule the world, whereas ants eat our leftovers and chimps are locked up in zoos and research laboratories.”

If only all fictions were created equally. Some, of course, can be ennobling. “If we take man as he really is, we make him worse,” said Viktor Frenkl. “But if we overestimate him, if we seem to be idealists … we promote him to what he really can be.” William James said much the same in his landmark address from 1896, “The Will to Believe”:

Suppose, for instance, that you are climbing a mountain, and have worked yourself into a position from which the only escape is by a terrible leap. Have faith that you can successfully make it, and your feet are nerved to its accomplishment. But mistrust yourself, and think of all the sweet things you have heard the scientists say of maybes, and you will hesitate so long that, at last, all unstrung and trembling, and launching yourself in a moment of despair, you roll in the abyss. In such a case (and it belongs to an enormous class), the part of wisdom as well as of courage is to believe what is in the line of your needs, for only by such belief is the need fulfilled. Refuse to believe, and you shall indeed be right, for you shall irretrievably perish.

Henry Ford put it in simpler terms: “There are two kinds of people: those who think they can, and those who think they can’t. And they’re both right.”

If James and Ford were speaking of beliefs transformed into truths, here we are dealing with their inverted form: intention-beliefs that, once uttered, reveal themselves as lies. Thought privately, statements of this nature might be true. Declarations like, “Lemons are the most delicious fruit,” or “Indiana is the greatest state in the Union.” If uttered aloud, however, they’re bullshit. As H.L. Mencken put it: “Whenever you hear a man speak of his love for his country, it is a sign that he expects to be paid for it.”

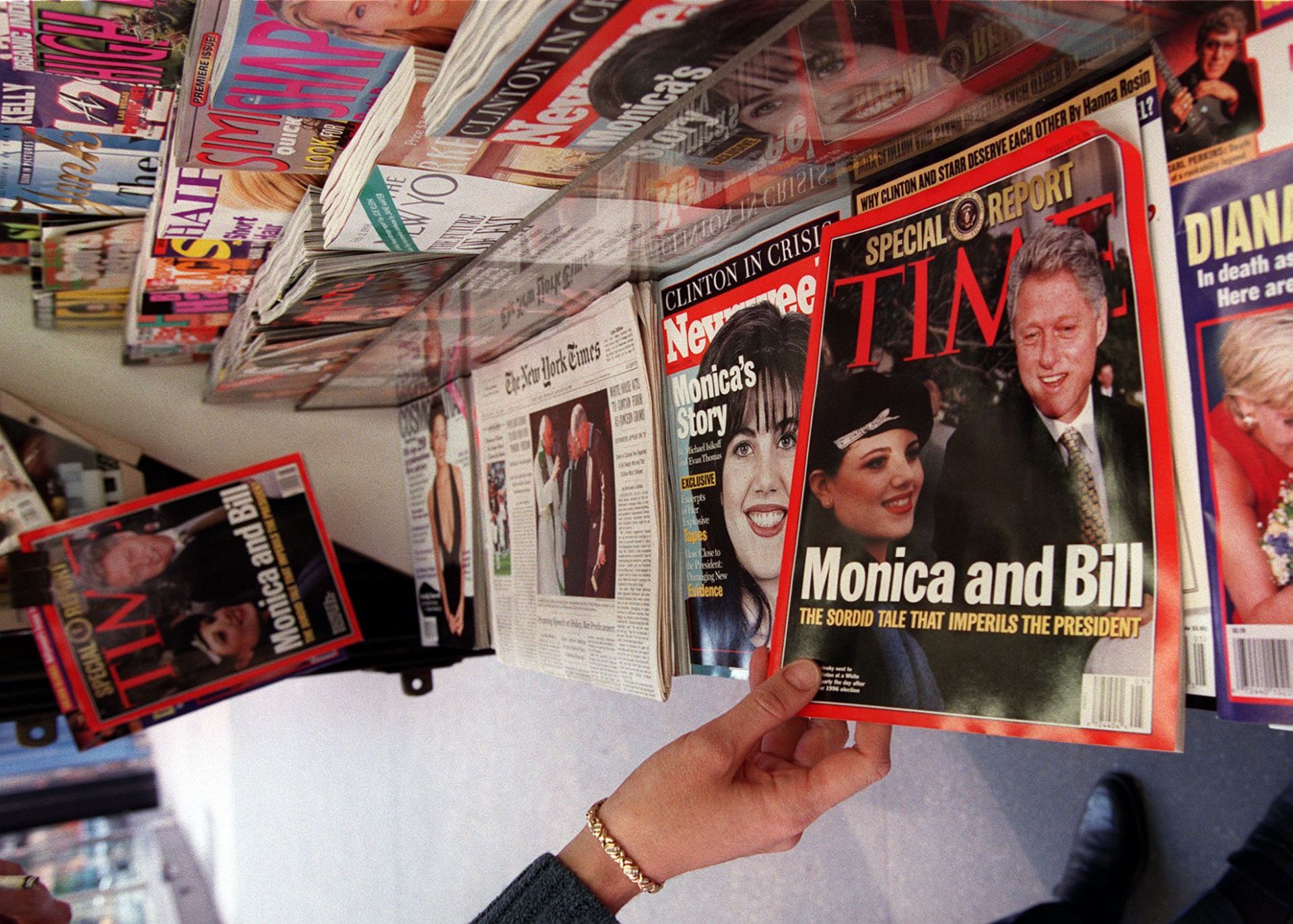

Bill Clinton was a maverick in this dark and ancient art. “I did not have sexual relations with that woman,” is only beaten by “I did not inhale.” But Slick Willie is far from alone. In May 2003, Bush II spoke from the USS Abraham Lincoln with the words “Mission Accomplished” emblazoned behind him. “When the president does it,” Tricky Dicky told David Frost, “that means it is not illegal.” When it comes to Donald Trump’s prevarications, it’s hard to pick a favorite. “The crowd was wonderful,” he told an audience at CIA headquarters after his inauguration. “I looked at the rain, which just never came.”

If honest exceptions such as Jimmy Carter exist (“I committed adultery in my heart many times”), they are a lonesome lot. Individuals yield to systems and societies, rarely vice versa. And public opinion is both fickle and ferocious. One day, marijuana is the scourge of the silent majority, the next there’s a dispensary in every strip mall. Politicians can be forgiven for failing to foresee these volte-faces.

Visible as they are, politicians are far from the only guilty party. Even our most beloved media outfits proudly display their perfidy. Which is the bolder claim: “All the news that’s fit to print” or “Fair and Balanced”? If you have to say it, dear reader, it isn’t true. In its defense, the fourth branch of government often learns from the first three. In 1949, for example, the Department of War became the Department of Defense — just as the Cold War was giving cover to global U.S. hegemony. Even calling the war “cold” is proof of our little theory — a chilly conflict indeed when nearly 20 million perished.

An acquaintance once defined humanity as “monkeys who make promises.” A more fitting definition might be “adult children who make lies.” Of course, we don’t always lie, and we don’t always want to. As Robert F. Kennedy said of Lyndon B. Johnson, whose college nickname was “Bullshit Johnson,” “He just lies continually about everything. He lies even when he doesn’t have to lie.”

There’s a fun word psychologists have for compulsive or pathological lying: mythomania. Some of us do it for fun, but most of us do it for gain, whether financial, romantic, political or social. In “Lying in Politics: Reflections on The Pentagon Papers,” Hannah Arendt suggests that all action requires a good bit of fibbing:

A characteristic of human action is that it always begins something new, but this does not mean that it is ever permitted to start ab ovo, to create ex nihilo. In order to make room for one’s own action, something that was there before must be removed or destroyed, and things as they were before are changed. Such change would be impossible if we could not mentally remove ourselves from where we are physically located and imagine that things might as well be different from what they actually are. In other words, the ability to lie, the deliberate denial of factual truth, and the capacity to change facts, the ability to act, are interconnected; they owe their existence to the same source, imagination.

What, if anything, are we to take away from this? A simple lesson — if something has to be said, and said in public, there’s a decent chance that it’s untrue. Why doesn’t Ecuador go about denying the Armenian genocide? Why does Congress pass a bill equating anti-Zionism with antisemitism? Why did liberals advance Russiagate? Why must headlines in Washington insist that Israel isn’t trying to wipe Gaza off the map?

In making these blatant, black-and-white public pronouncements, the speaker is giving us critical insight into their inner mind, their hopes, fears, projects, plans and projections. If it seems they’re misleading us, think again. What they’re really doing is giving an awkward shortcut to the truth. “Believe nothing you hear, and only one half that you see,” wrote Edgar Allen Poe. But with claims of this sort, perhaps it’s better form to believe their opposite.

In August 2021, for example, as the Taliban closed in on Kabul, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken told reporters: “This is manifestly not Saigon.” By which he meant: This manifestly is Saigon. It’s a simple translation tool. To see real results, introduce it into your private life. If someone at a party tells you they speak eight languages, what they really mean is: They don’t speak eight languages. They may have studied eight languages, and should like to speak eight languages, but speak eight languages they don’t.

On some deeper subconscious level, the act of uttering something aloud may be an attempt to convince the speaker herself of its veracity: “I just love going fishing.” “What a beautiful cardigan.” “I can’t wait for the school year to begin,” as if by professing something, it will come true. It’s something adults often chide children for: make-believing. When applied to grown-ups, this might be called making ourselves believe. If only it worked more often. As Cormac McCarthy writes: “The world is quite ruthless in selecting between the dream and the reality, even where we will not.”

Examples of this are endless. One friend of the writer often refers to herself as having been the “most beautiful woman in the room” at the time of the tale being told. This reveals two things. One, she would have liked to have been the most beautiful woman in the room. Two, she was not.

Another friend took it one step further. Assigned to teach a subject in which he had neither expertise nor any basic understanding, he played a small trick on his students. On the first day of class, he asked them to raise their hands and point to the smartest person in the room. Baffled, they lifted their arms but were too shy to point to any one person. “Now direct your hands to me,” he told them. It was far from true — at least in regard to the subject material — but they did as instructed. He had no trouble from them for the rest of the term.

In a wonderful little book called “Xenophobe’s Guide to the Americans,” Stephanie Faul touches upon this point with wit and understanding. “In the United States, it’s definitely not how you play the game that matters. It isn’t even really whether you win or you lose. It’s whether you look like you win or you lose—more specifically, win.” Every tyrant and neighborhood tough knows this, too. Is it any surprise that Saddam and the ayatollahs built monuments to commemorate their victory in the Iran-Iraq War? As Epictetus said: “It’s not what happens to you that matters, but how you react to it.” Or, in our case, how you market it.

If anyone can grasp this treacherous reality, it’s children — the clever ones, at least. Numerous studies show that children who lie at a young age are estimated to have IQs that are roughly 10 points higher. Sadly, or happily, depending on your penchant to prevaricate, the same goes for adulthood. In the bullshit jobs economy, it is often those best skilled at pretending to work that get paid the most. As Bertrand Russell put it: “Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so. The first kind is unpleasant and ill paid; the second is pleasant and highly paid.”

So next time you pick up the newspaper, turn on the television, or listen to a fable from a friend or a foe, ask yourself the question. Did they oblige themselves to say that? If so, there’s a decent chance they’re fibbing you. Maybe that’s why we never see ads for salt, butter or corn. We hold those truths, at least, to be self-evident. When Walter White says, “What I do, I do for my family,” it’s a kind of tortured confession. What he means is: I do this shit for me.

An American diplomat once said: “If you lie to people, they will find out. And they will hate you for it.” Yet societies aren’t so keen on Cassandras, either. The Turks have an excellent saying: “The truth-teller is kicked out of nine villages.” But toward what end? Ernest Renan knew the importance of avoiding certain realities. “The essence of a nation is that all of its individual members have a great deal in common and also that they have forgotten many things,” he said in 1882. “Every French citizen has forgotten St. Bartholomew’s Day and the 13th-century massacres in the Midi.”

So whenever you see a headline that says, “Terrorists Use Hospital as Command Center,” “There Is No Famine or Actual Starvation” or “Government Prioritizes Human Rights,” salute the editor, for they’ve done you two big favors. First, they’ve led you one step closer to the truth. Second, they’ve shown their hand. “Whenever someone’s trying to scam you in the bazaar, they call you brother,” says Dorduncu Veysel, a journalist in Istanbul. “It’s a fundamentally coercive act, the saying of something untrue, an intellectual mugging.”

Middle-aged men in the Eastern Mediterranean often remind you that we’re all brothers under God, whatever our religion may or may not be. While sympathetic to this line of reasoning, it does make one wonder: Why do they only utter this in areas where great violence has occurred? “Then again,” says Veysel, “The first murder in history was a fratricide.”

On Feb. 8, President Joe Biden had arguably his toughest day in office. Not for admitting publicly that Israel had been “over the top” in Gaza — or for referring to Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as the president of Mexico. But for a special counsel’s report in which lawmakers referred to him as a “well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.”

Eager to prove our theory, Kamala Harris called the report’s comments “gratuitous, inaccurate and inappropriate,” for which she might have said “reasonable, accurate and appropriate.” A congressman from New York, Dan Goldman, upped the ante by saying he did not have “any concerns” about Biden’s abilities, the FT reported. The democratic senator from Maryland, Chris Van Hollen, followed suit: “I am absolutely confident … that he is the right person to lead the country for another four years.”

While this piece is neither the time nor place to assess the president’s bona fides, one wonders if he’s not privy to our point. His answer to reporters? “My memory is fine.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.