I first met Robert Fisk when I was 12 in a chance encounter in 1993 at Smith’s supermarket, on the corner of Sadat and Makdissi streets. The owner, Patrick Smith, loved sharing memories of a Ras Beirut that belonged to his generation. On one occasion Patrick was recounting a childhood memory to a British-accented customer in line behind me, groceries and gin bottle in hand, waiting patiently for his turn. “Ronnie, could you please lift your Pepsi can for Robert?”

I wouldn’t think about Robert until years later. I was an undergraduate student in Virginia shopping for textbooks at the campus bookstore. There at the entrance display alongside other bestsellers lay the paperback edition of his “Pity the Nation.” The book had inspired a post-war generation of journalists and storytellers. I bought it and read it three times. That same semester, I dropped my engineering studies to pursue a degree in political science and history. I suddenly understood – or so I thought – everything that happened in Lebanon’s civil war. The book was filled with day-by-day accounts of life in the war: Israeli and Syrian checkpoints; Fatah, Amal, and other militias; U.S. Marines; Lebanese in Jounieh hosting Israeli troops as Ariel Sharon laid siege to Beirut. Robert’s unequivocal narrative makes clear Palestinian suffering was a direct consequence of the Holocaust, and that unchecked Israeli power had left the region in tatters. This was an eloquent contrast to the confusing conversations I grew up around at home – the endless, circular political discussions with relatives and friends. Robert gave me – and many like me – a story with structure that resonated, and a belief that the Palestinian cause was paramount.

Then came the 9/11 attacks and their politicizing effect. I joined Students for Justice in Palestine in late 2001 and started pretending to understand Edward Said’s work. I bought a Palestinian flag that I hung above my bed. To inappropriately borrow from Robert: It was Palestine. Palestine. Palestine. In the minds of our student cohort, the connection between 9/11 and the Palestinian cause was obvious: We believed the root cause of 9/11 was an unresolved Arab-Israeli conflict and an occupied and displaced Palestinian population that deserved a state. Robert would not have disagreed.

We soon invited Robert to give a lecture on campus. He began by defending the Afghan refugees that beat him while he was reporting from the Pakistan border in late 2001. He shared a passionate portrayal of Palestinians evicted by Israeli settlers and ended by lambasting all that is American foreign policy, I made my way to meet him. He shook hands with many like me – Lebanese, Palestinians, all flavors of Arab-Americans. We championed his tirades against other journalists that lacked his courage to speak truth to power. Robert was our hero. There was right and there was wrong, and he was right. And any criticism of his “going native” in the aftermath of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq we dismissed as polemic and anti-Arab.

My third encounter with Robert was at a conflict resolution course in Nicosia, Cyprus, in June 2006. I was in my mid-20s and had purchased his long “The Great War for Civilization.” I skimmed parts of its 1,000+ pages but did not give it the time it deserved. In the days before Kindle, those extra pounds traveled with me wherever I went. I was proud to have the book with me when Robert was flown in from Beirut to Nicosia to speak about his work. He celebrated Israeli journalists who condemned Israel’s occupation. He lambasted the laziness of reporters embedded with the U.S. military in Iraq. His passion for the written word was infectious, and the principles and ethics he shared – at least from the audience’s perspectives – placed him above the fray. Those encounters with Robert made me appreciate hard facts, first-hand reporting, and the real risks journalists faced in war zones. He was placing the story of human suffering over patriotic diatribe, and we were swept away by it.

I returned to Beirut later that month, and a few days later the July War broke out between Israel and Hezbollah. Ten years earlier, Israel had launched an offensive on Hezbollah it called Operation Grapes of Wrath. But the 2006 war was a more brutal and costly endeavor. After it ended, I was managing a student pension across the street from the same Smith’s supermarket where I first met Robert. I visited Patrick Smith a final time days before the supermarket shut down. He mentioned Ras Beirut would never be the cosmopolitan neighborhood he grew up in the 1950s and ‘60s. Makdissi Street had become trendy with student cafes and bars. The ancient tenant laws that kept older shops running were being revised. But I was enjoying my own limited chapter of the neighborhood’s history … which largely revolved around drinking.

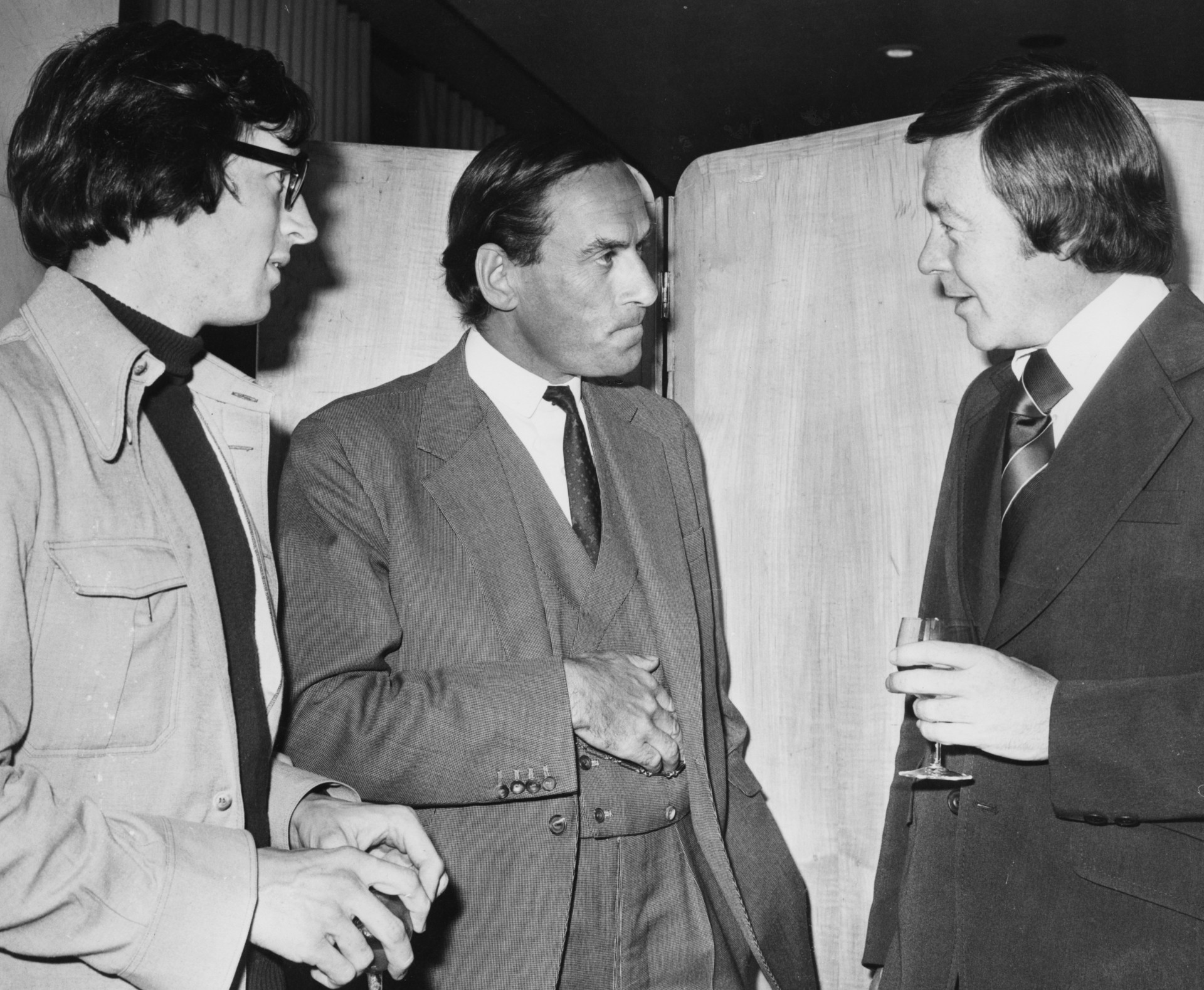

I think my first honest meeting with Robert was the aftermath of the May 2008 fighting that saw Hezbollah take over much of Beirut and brought Lebanon to the brink of another civil war. We met chaos with debauchery. Enough of my circle knew him to invite him over for a drink (or two … or three). He arrived sober, drank two bottles of wine at our table, and began mocking us at every sentence we uttered. Without going into unnecessary detail, he was terrible company.

The journalist and writer from my youth I still respected. But the man I knew as an adult was company I could do without.

Later I would reluctantly turn to him when I was starting my WalkBeirut tour in early 2009. I had launched it as a storytelling walking tour through Beirut, narrating its multi-layered history. The tour was also an homage to Samir Kassir, a fellow journalist, teacher and fantastic historian who was assassinated in June 2005, paying the ultimate price for demanding that we learn from our past. Robert had written the foreword to the English edition of “Beirut,” Kassir’s historical opus, a manual I continue to reference today. But when I could not find something about Beirut in the book, I would call Robert to help me locate references and verify sources. Yet despite an initial interest in what I intended to cover in the tour, he mocked what he chided as a “tourist-friendly” version of history not worth sharing. I soon began excusing myself from occasions where he would be around. The journalist and writer from my youth I still respected. But the man I knew as an adult was company I could do without.

It took me still more time to see Robert’s other flaws. The outbreak of the Syrian revolt-turned-war in 2011 drove many of us to reconsider his writings. We admonished his apparent defense of Bashar al-Assad’s atrocities and the doubt he cast over the regime’s complicity in chemical weapons attacks. He would still occasionally write eloquent pieces on reviving Lebanon’s rail network, environmental degradation from mountain quarrying, and even the work of a painter (and friend) whose work I knew well. In those articles I sensed Robert was reminiscing about a Lebanon he first visited just before the civil war broke out 45 years ago. He was watching Lebanon decay, and his words reflected our collective loss. But they were overshadowed by his refusal to acknowledge or criticize Assad’s crimes, and it was only when tragedy hit home that I felt any urge to see Robert again.

I approached Robert on the corniche, weeks after my father’s assassination in December 2013. He was walking toward the Ain El Mraiseh neighborhood and looked at me without the faintest idea who I was. I reintroduced myself, this time as “Mohamad Chatah’s son.” Once his memories of me returned he was quick to note he never realized the connection, and that I didn’t carry myself as a “politician’s son.” That was the extent of his empathy, and certainly of his curiosity. I sensed Robert might have had kinder words for the son of someone who had challenged the “imperialist” West. The killing of my father, a critic of the Assad regime and Hezbollah’s sub-state weaponry, seemed like a forgotten footnote in the regional struggle among competing actors. He appeared more bothered that the “politician’s son” he had known for years was delaying his meeting downtown.

Robert had written an obituary on my father’s legacy. I spoke my mind. I told him I thought the obituary was misleading,

Robert had written an obituary on my father’s legacy. I spoke my mind. I told him I thought the obituary was misleading, its emphasis on Saudi Arabia wrong. The obituary begins with, “It was a bomb against the Saudis. Mohamad Chatah represented the most reasonable face of the Saudi-supported March 14 party in Lebanon.” It goes on to say, “… he was just another face of the Sunni-Shia cold war which has burst through the crust of Muslim society over the past 30 years …” I told him I thought my father deserved better, and disagreement with Hezbollah’s arms was a Lebanese position born out of a belief in Lebanon’s sovereignty rather than Saudi Arabia’s influence in the region. He responded by chiding the Americans who, in his mind, were hellbent on tearing Lebanon apart in order to destroy Hezbollah. He added his less-than-flattering view of voices he found equally determined to destroy him, and he reminded me he was running late.

I stopped Robert and insisted that adopting aspects of Assad’s narrative and giving Hezbollah an unnecessary pass was crushing his reputation. A persistent affection for perceived underdogs was tossing his legacy to the sea. I pointed at the Mediterranean when I said that. And when I turned to the soothing waters, I saw the vivid depictions of the views from his balcony during the darkest years of Beirut’s fighting. The tranquil coast in front of him, and behind the war-torn city he called home. The epic tales of East meeting West, empires and conquests, Ottoman statelets and European mandates, great powers vying for interest. In the middle was Lebanon’s history, which we endlessly debate rather than understand. And for a moment, I remembered Robert as the cherished visitor who told its story like few others.

Robert Fisk championed the underdog. He empathized with the victim. But those labels were applied solely on his terms. His views ran contrary to what I saw as a genuine yearning for decency and democracy. Other famed storytellers had found their way to empathize with differing sides rather than continue to cast blame. Ziad Doueiri had given us his left-leaning sympathies in 1998’s “West Beirut,” but also showed us East Beirut’s insecurities and emotions through 2015’s “The Insult.” Fouad Ajami wrote the “The Arab Predicament” in 1981 and was deemed a pro-American/self-hating Arab for decades, but “The Syrian Rebellion” – published a year before his passing in 2012 – praised Syrian protesters risking their lives against tyranny. I could sympathize with the victims Robert wrote about without dismissing the suffering caused by his perceived underdogs.

In the end, Robert chose rigidity over complexity and empathy: a calcified worldview that no longer matched our current chapter of history. The West was always wrong. Israel remains our gravest threat. And only those fighting both deserved his empathy. That Robert could only understand my father’s assassination as an attack on a pro-Western regional power showed the narrowness of his compassion and limits of his sympathy.

“You know where to find me,” were the last words I heard as he faded to the Green Line, between Beirut’s skyline and shore.