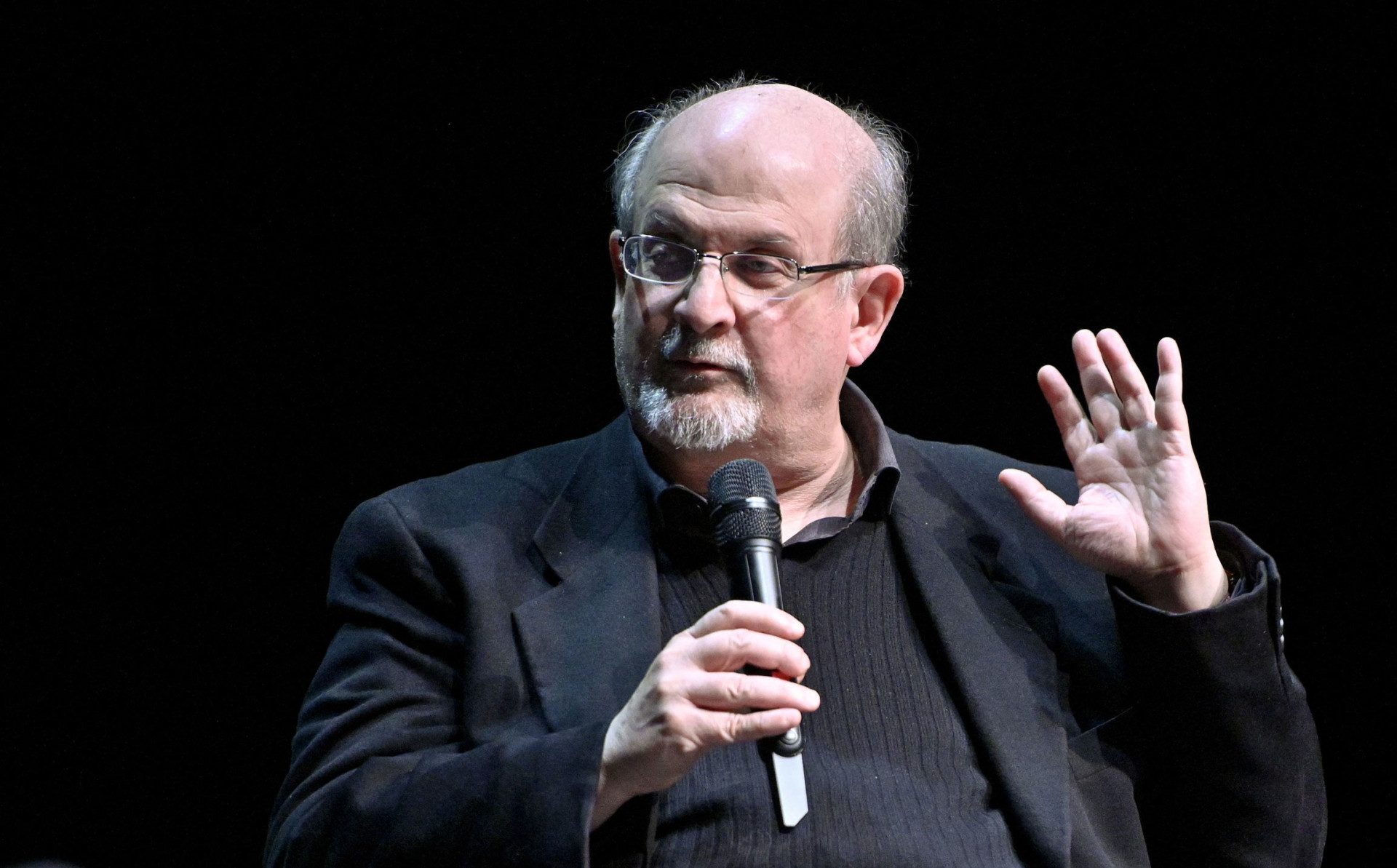

In April 2001, Indian-born British author Salman Rushdie was among the guests of honor at the Prague Writers’ Festival. Having only recently come out of years of hiding, Rushdie was clearly frustrated with the massive security detail that followed him everywhere.

“To be here and to find a large security operation around me has actually felt a little embarrassing,” he told the reporters. “I spent a great deal of time before I came here saying that I really didn’t want that.”

It was a sentiment he often repeated in the years to come, saying “things are fine now” in 2019, and just a month ago telling a German magazine he had a “mostly normal” life. With Rushdie having celebrated his 75th birthday in June, the 1989 fatwa of the long-deceased Ayatollah Khomeini seemed to belong firmly in the past.

And so there was very little security last Friday at an event with Rushdie in the small town of Chautauqua in New York state, allowing Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old American of Lebanese descent, whose social media and phone is filled with pro-Iran content, to rush onto the stage and stab Rushdie repeatedly.

Whether Matar was acting on his own or with direction from Tehran is now the big question. The question, however, can be misleading. The Iranian regime utilizes a wide range of contacts, operators and middlemen. A typical Iran-backed attack might not start with a detailed plan in Tehran but can initiate from a mid- or even low-level operative in one of the many affiliates of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) — be it Hezbollah, the jewel in the crown of Iran’s Axis of Resistance, or one of the lesser groups — who has happened to stumble upon the right opportunity. Initial reports, by VICE News citing intelligence sources, have claimed that Matar was in touch with IRGC operatives. What is already clear, regardless of the details that will surface in the months to come, is that the Iranian regime is as implicated now as it was in 1989 when the fatwa was issued.

Ever since the fatwa was issued 33 years ago, the regime has consistently campaigned for Rushdie’s murder. The persistence of this bizarre quest for the murder of a novelist helps us understand key facts about this regime.

It hasn’t always been so combative. In 1998, Iran and the U.K. re-established diplomatic ties after Iranian diplomats declared that Tehran wouldn’t attempt to kill Rushdie. But the diplomatic turnaround didn’t last: It withered in 2005 along with the reformist administration itself of then President Mohammad Khatami, who today is vilified in the official press and whose image is banned from appearing in media. Many of his former comrades, such as Mostafa Tajzadeh (a deputy interior minister in his administration), found themselves in jail, and the main political parties that backed him remain banned. Not only did Khomeini’s successor as the regime’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, repeatedly reaffirm the fatwa (prominently in 2005 and as recently as 2019), the IRGC and its many outlets regularly run articles that criticize the long-marginalized Khatami for his 1998 decision. An article celebrating the fatwa was published as recently as five days before the Chautauqua attack by a website affiliated with Iran’s government. Of the most material consequence is the bounty that Iran has kept on the head of Rushdie. In 2012, the 15 Khordad Foundation, whose head is appointed by none other than Khamenei, increased the bounty to $3.3 million, and its existence is regularly promoted by IRGC outlets.

Iranian reactions to the Chautauqua attack leave no doubt as to the state of things in 2022.

Today, following a few days of stony silence, the foreign ministry’s spokesman, Nasser Kanani, finally declared that Matar had no links to Iran but also went on to condemn Rushdie for allegedly “crossing the red lines of 1.5 billion Muslims and all other believers of divine religions.” He affirmed that for Iran, “the only parties deserving of condemnation are Rushdie and his supporters.” There had been many more forthright Iranian reactions over the weekend. Yesterday, the newspaper Iran, the official organ of the Iranian government, ran an editorial that celebrated the attack on Rushdie. It boasted that “33 years after His Excellency Imam Khomeini ruled on the apostasy of Salman Rushdie, a non-Iranian in the heart of America committed the most holy act of God.” It claimed that “popular sympathy and happiness” had followed the attack. Praising Matar, it claimed that this represented a “new phenomenon, deserving of theoretical study” that showed that “in the heart of the modern world, the orders of God are still alive in people’s hearts.”

The hardline daily Kayhan, whose head is appointed by Khamenei, had already celebrated the attack in no uncertain terms: “We salute this brave man who attacked the apostate and cruel Salman Rushdie in New York and we kiss his hands who knifed and tore the neck of an enemy of God.” On Sunday, it had another telling headline: “Salman Rushdie, victim of divine revenge; Trump and Pompeo are next.”

“The attack on Salman Rushdie shows that it is not hard to take revenge from the criminals on U.S. soil,” Kayhan claimed.

The daily Jame Jam, organ of Iran’s state broadcaster, ran a most chillingly crude defense of the attack. Following reports that Rushdie was likely to lose an eye, the daily published a cartoon of him, featuring horns and missing one eye, with the headline: “The Satan lost an eye.” It celebrated the attack as “clearly showing the revenge of the Front of the Right against the Front of the Wrong goes beyond time and place.”

A variety of theological endorsements of the attack has also quickly appeared in official Iranian media. On state TV’s Channel Four, cleric Mohsen Qanbarian assured the viewers that assassinating Rushdie did not count as an illicit terror attack: Rushdie was a legitimate target since he was “under the protection of the enemy.” Speaking to the IRGC-backed Fars News Agency, Ayatollah Hossein Radai, a professor at Tehran’s Shahed University, said: “In Islam, assassination is illegal, but a judicial execution is something different.” Since he was a Muslim who had left his religion, i.e. an apostate, killing of Rushdie was allowed, Radai insisted.

The attack’s timing, at a decisive stage in the Iranian nuclear negotiations, has led to conspiracy theories. Was this a false flag operation aimed at derailing the talks? But when Mohammad Marandi, a Virginia-born pro-IRGC commentator in Tehran and a member of the negotiating team, posited the idea, he was quickly shouted down by many regime supporters. Sayid Lavasani, a former Friday prayer leader of Lavasan, said the attack was a “good event” and asked: “Now Mr. Marandi is worried about the Iranian nuclear deal? Revolutionaries are happy today, not worried.”

Amirhossein Sabeti, a state TV anchor, attacked Marandi’s tweet as “shameful” and added: “the JCPOA [Iranian nuclear deal of 2015] had no fruits for the country so why are you so dishonorably begging for the revival of that colonial deal?” Many others repeated a similar position.

In fact, what is particularly outrageous to many of these critics is the idea that Iran should prioritize a nuclear deal, aimed at lifting of the sanctions and economic alleviation, over such a key fatwa of Ayatollah Khomeini. For them, the very idea that killing off Rushdie could disrupt the revival of JCPOA shows why this deal should be rejected in the first place. The revolutionary cause must be prioritized over diplomatic niceties.

Abdollah Ganji, editor-in-chief of Tehran daily Hamshahri, took to Twitter to remind his audience that Khomeini’s fatwa in February 1989 had come shortly after the Iran-Iraq war ended, when the country was in dire need of foreign investment and reconstruction aid. Ganji quoted Khomeini’s own words at the time to show that the Grand Ayatollah had criticized those who urged priority of diplomacy over the fatwa.

“All the Zionists and the arrogant of the world are now supporting Rushdie,” Khomeini clamored in a letter to clerics on Feb. 22, 1989. “Maybe they believe that we are afraid of the European Union or an economic siege and will thus give up executing the order of God.” He claimed it was part of a wider movement against Islam, and continued to say that: “I am afraid that, ten years from now, some would attempt to see whether the Islamic fatwa and the order of execution for Rushdie was diplomatic or not; those who will say that ‘we shouldn’t be naive — since the Western countries and the EU are against us, we should forgive those who insult the Prophet and Islam.’” Khomeini was clear that there could be no compromise: Even if Rushdie became “the most pious man in the world,” he should still be killed.

Ganji’s quoting of these words by Khomeini was telling. The Grand Ayatollah seemed to have been predicting, and condemning, the 1998 backtracking decision of the Khatami administration that had helped bring about normalization of ties with Tony Blair’s U.K. In fact, Khomeini’s move in issuing the fatwa in 1989 had little to do with the content of Rushdie’s book (which had come out a year before and which Khomeini never read) and everything to do with his desire to prove his radical Islamist credentials and prevent a normalization of ties with the West that risked emptying the Islamic Revolution of its content. Just a few months before, Khomeini had accepted a U.N.-mediated ceasefire in the war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, thus ending his long-lasting promise never to stop the war until Saddam was overthrown and revolutionary Iran could expand its revolution in the region. Khomeini’s humiliating retreat was, in his own words, akin to “drinking a chalice of poison,” and he now needed to show the Muslim world that he wasn’t a man of compromise. When he died a few months later, the fatwa became a key part of his legacy.

It wasn’t the EU countries that first broke ties with Iran in response to the fatwa; it was the other way around. While some European countries had recalled their ambassadors (without downgrading the ties), it was Iran that, following a parliamentary vote on March 7, 1989, reduced its ties with the U.K. to charge d’affaires level.

Almost a decade later, in 1997, Khatami’s election, backed by massive desire for change among the population, started a period of change for Iran. But the reformist president was stymied at every level by the IRGC and Khamenei, who made the militia his base as he crushed the reform movement.

The 1998 retreat on the Rushdie fatwa is part of this history. Not that Khatami and his comrades had ever been fans of Rushdie. As culture minister in 1989 (when the fatwa was issued), Khatami had gone out of his way to defend the execution order and not once did he say that it was wrong, despite all his claims at representing a peace-loving Islam. This was, after all, the same man who also defended other strictures such as capital punishment for gay people. Khatami’s own culture minister, Ataollah Mohajerani, went even further: He wrote a 250-page book in defense of the fatwa that, even in 2022, he continues to defend from his London exile.

Kamal Kharrazi, Khatami’s foreign minister, is known for having met with his British counterpart, Robin Cook, on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly in New York in September 1998 and declaring that Iran would not attempt to kill Rushdie. But he was often more equivocal when speaking about the fatwa in Persian. He would, for instance, say that Iran would “neither assist or hinder” attempts on Rushdie’s life. In other words, much like the reform process in Iran, the retreat from the fatwa had always been partial and conditional and, in any case, buried long ago, along with the prospects of the reformists.

Why would a major state like Iran persist for decades in a seemingly irrational open quest for the murder of a harmless novelist even if that brings it economic and political isolation? Answering this question can go a long way in tackling the thorny task of understanding the Iranian regime.

After all, several similar questions could be asked. Why do Ayatollah Khamenei and the IRGC persist in a consistent campaign of Holocaust denial, even though they know how poisonous this can be for their image? Why has the Iranian regime persisted in maintaining rules such as enforcing mandatory veiling on all women everywhere or banning women from sport stadiums?

Those who believe these are due to the fundamental irrationality of Islamists in power in Tehran miss the point. These goals are only irrational if you presuppose an automatic desire for global integration. But, as Karim Sadjadpour has recently argued, this is precisely the conundrum of US-led Western policy toward the Iranian regime: “By and large, the United States has sought to engage a regime that clearly doesn’t want to be engaged and isolate a ruling regime that thrives in isolation.”

Khamenei and the IRGC have long known that extensive contacts with the West would require Iran becoming a more “normal country” and that this will threaten their rule. They have successfully marginalized and excluded those factions of their own regime that favored either democratic reform (like Khatami) or simply more West-facing economic policies (like those favored by former President Hassan Rouhani.) At some point in the early 1990s, Khamenei had favored such economic policies himself, which is why he then endorsed a pro-free market turn in the economy. But he soon realized that economic reforms could endanger fundamentals of the revolution as they would empower factions that wanted to get rid of obstacles on the path of trade: obstacles such as the fatwa on Rushdie.

In simpler words, Khamenei insists on “abnormal” elements such as the order to kill Rushdie, Holocaust denial, misogynist rules or severe anti-Americanism for the same reason that Khomeini was invested in similar policies: maintaining the radical Islamist and anti-Western credentials of the Islamic Revolution and excluding from power those who would be more attuned to the Iranian public demands for a more “normal life” (an actual slogan raised by Iranians on the streets and in social media hashtags). “Normalization” of life, which has repeatedly been demanded by vast swathes of people and even many factions of the regime itself, counters its quest for uncompromising Khomeinism.

The Western response to the 1989 fatwa was a litmus test that many failed. Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter effectively joined the attacks on Rushdie in a New York Times op-ed and accused him of committing an “intercultural wound that is difficult to heal.” In contrast, many authors rushed to the defense of their comrade in pen: from Stephen King, who refused to let stores in America sell his book if they refused to carry “Satanic Verses,” to Arab intellectuals such as Edward Said and Sadik Jalal al-Azm who put their differences aside to maintain a robust defense of Rushdie.

This time around, a similarly robust defense of freedom of expression is in order. But, more important, this episode makes clear the need for countering a regime that’s open about the worst of its intentions. This doesn’t mean cutting diplomacy with the Iranian regime which, as explained above, actually thrives on isolation. But it does mean being clear-eyed about the identity of this regime and what it stands for; which means overcoming a growing cottage industry, not least in Washington, D.C., that aims to obfuscate. It also means supporting the brave men and women of Iranian civil society and democratic opposition who have countered and fought the regime for years and know it best.

We could all take a page from a group of Iranian religious intellectuals who published a joint statement to show their disgust at the attack on Rushdie. Signed by luminaries such as Hasan Eshkevari, a former reformist member of Parliament; Alireza Rajayi, a leading progressive journalist; and scholars Soroush Dabagh and Yasser Mirdamadi, the statement condemns “the terroristic and brutal attack” by Matar and goes on: “Today, we wholly stand with victims of terror and loudly declare that fundamentalist Islam doesn’t represent most Muslims … . We hope for a day when religion and state are separated in Iran and no government can use any tools, including religion, to repress freedom and eliminate dissidents, just to survive in power.”