Fred Hampton, chair of the Black Panther Party’s Illinois chapter, did not know he was about to die but he knew things were getting dangerous. In the months leading up to his 1969 murder at the hands of Chicago police, he often found himself surrounded by white street toughs who had migrated from the Jim Crow South, unemployed and unemployable, with slick-backed hair and denim jackets emblazoned with the Confederate flag. But these men, who called themselves the Young Patriots, were not there to menace Hampton. They were there to provide security.

“Our job was to organize poor white people. You know, to fight for freedom, fight for their rights and to fight against racism,” Hy Thurman, one of the organizers of the Young Patriots, told me. Like almost everyone else in the group, the Tennessee-born Thurman moved to Chicago in search of a better life and instead found poverty and police brutality. The Young Patriots stood with the Black Panthers not out of white guilt or a white savior complex but because they shared an enemy and a cause. Leadership in both groups saw racial justice as inextricably linked with economic justice. You could not have one without the other.

For at least a generation, the American left has largely abandoned issues of class to focus on race. We advocate for Black and brown representation in the halls of power, rather than questioning the power structure itself. Attempts to analyze and address white poverty are often treated as attempts to whitewash racism and squander resources on a privileged class. Conservatives have taken full advantage of this to recruit poor whites into their culture-war army; their success reinforces the idea that poor whites are inherently conservative. When liberal strategists talk about appealing to the white working class, they usually mean an abandonment of progressive policy goals like taxing the rich and universal health care. What if that’s wrong? What if the way to win over the white working class — and to address one of the root causes of racism — is not to move rightward but to embrace ideas so progressive that they haven’t appeared on a mainstream political platform since Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society?

If rising enthusiasm for unionization is any indication, the white working class is already more progressive than most pundits think. Support for unions — which culture war proponents have tried to brand as “un-American” for their Marxist and socialist roots — has gone from 48% in 2008 to 70% this year. While Democrats are still more likely to support unionization than Republicans, the majority of low-income Republicans now believe that America’s decades-long trend of decreasing unionization is bad for workers. While the proportion of unionized American jobs has remained at around 10% since 2021, union election petitions filed increased by 53% — from 1,638 to 2,510 — between 2021 and 2022 alone, suggesting that it is anti-union regulations, not worker preferences, that keep the number of union jobs from rising higher. Recent surveys suggest that working-class voters support progressive economic policies when the proposals are stripped of liberal jargon; a July poll in swing states showed that 59% of voters without a college degree support free college education, 63% support single payer healthcare, and 76% support a cap on rent increases. This may help explain why a quarter of white voters for President Barack Obama without a high school diploma defected to Donald Trump in 2016. These candidates have little in common but both effectively used the language of economic populism.

Eight years later, as Trump and Democratic Party candidate Vice President Kamala Harris crisscross the Midwest in a bid to win over these same voters, both are using populist rhetoric to do it. Trump’s rhetoric is empty: During his first term, he made it easier for corporations to crush unionization efforts and harder for unions to hold corporations accountable. He also cut taxes on corporations and the rich. But can either party truly advance working-class interests when our campaign finance laws leave them so beholden to big corporations and wealthy donors? Perhaps the answer lies beyond our two-party system — with organizing by and for the working class.

Thurman is still doing this kind of work, five decades after the Young Patriots fell apart. He recently published an autobiography about his time with the group, “Revolutionary Hillbilly,” and when I read it this summer, the organizing ideas from more than 50 years ago still felt fresh.

When I called him in September, Thurman told me he believes that many working-class people are already radicalized, even if they don’t think of themselves that way. “A lot of poor people are living the Marxist theory in terms of thinking that they should own a part of what they produce,” Thurman told me. In other words, if you’ve ever noticed that your company makes far more off of your work than you receive in your paycheck, and if that seems unfair to you, you’ve articulated Marx’s concept of surplus labor in plain English. Contrary to right-wing talking points, the point of left-wing economic activism is to make sure workers receive fair pay, not to transform America into a Stalinist hellscape. “We have to let people know that without scaring them off,” Thurman said. “Because once you start talking about communism, when you start talking about socialism, they’ll say you’re gonna come get my money. You’re gonna come and get guns and all this. But that’s not true.”

Convincing a working-class Midwesterner that Marx had some decent points might sound difficult, but it’s probably no more difficult than selling a bunch of self-described hillbillies raised in the Jim Crow South on revolutionary anti-racism. And yet, that’s exactly the kind of transformation young college student activists in Chicago kicked off back in the late 1960s, not by lecturing impoverished white people about anti-racism and class struggle, but by demonstrating the ways these ideas could help all working class people. The student activists offered much-needed services, like help with obtaining welfare benefits, medical care and affordable housing fit for human habitation, and then helped the newly arrived white Southerners organize to demand these things themselves. As the new residents began to understand the reason for their miserable living conditions, it became obvious that other races were allies, not enemies, in their fight for economic justice. And, as poor white people interacted with poor Black and brown residents of Chicago, they saw that other races had it even worse than they did.

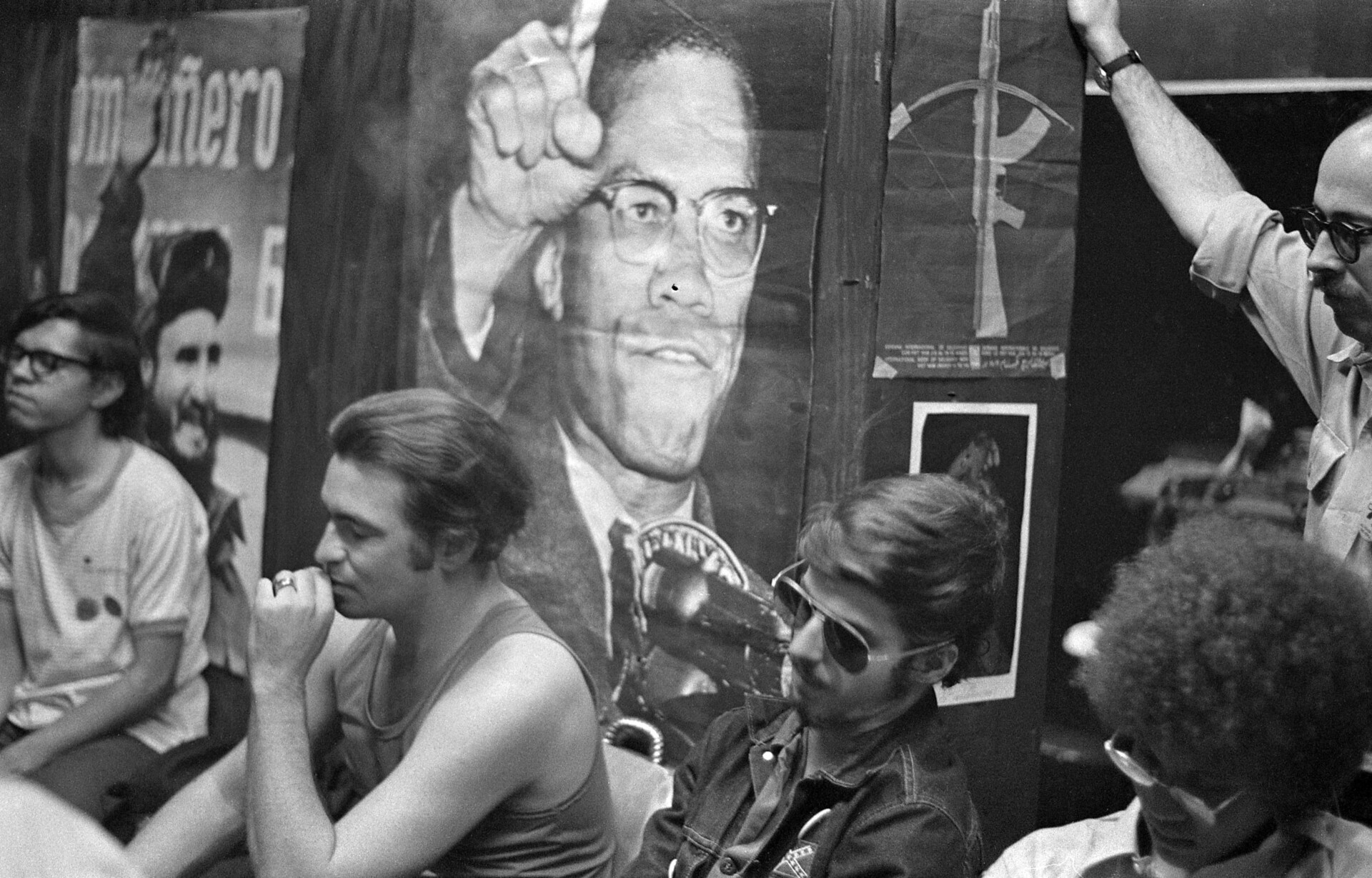

Hampton, not exactly infamous for coddling white people, saw class struggle and the fight for racial justice as identical and intertwined: Neither worked without the other. He led the way in forming a “Rainbow Coalition” with the Young Patriots and a radical Hispanic group, the Young Lords. They partnered for protests and events but remained structurally separate. “We were told back in the ’60s to go organize your own. Don’t try to organize the Black people. You organize your white people,” Thurman told me. The separation short-circuited the problem many activist groups still face: the tendency for white people to assume leadership roles within anti-racist groups. By organizing separately, they were better able to stand together.

Movements like the Rainbow Coalition and Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign believed that, if they united the American poor of all races, they could change the system. The FBI agreed. Director J. Edgar Hoover had long lived in terror of a “Black Messiah” capable of uniting people of all races in a class revolution, and he saw that potential in both Hampton and King. Though the FBI tracked, harassed and targeted both men before 1969, the full force of its infamous COINTELPRO strategy of destabilizing organizations through infiltration and violence did not hit until after these cross-racial efforts began. King was assassinated just as the Poor People’s Campaign, in which people of all races camped on the National Mall to demand economic justice, began to take off. The FBI helped Chicago police officers murder Hampton in his bed a few months after the Rainbow Coalition formed. The Black Panthers, Young Lords and Young Patriots found themselves buried in frivolous legal cases brought against them, which consumed most of their time and resources. The FBI also sent infiltrators to sow dissension, often by playing up racial tensions; a baseless rumor that the Young Patriots were affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan took an especially harsh toll. Within two years, the coalition collapsed.

“Some of us went underground but we never stopped organizing,” Thurman told me. In the decades since the Rainbow Coalition fell apart, the legacy of the Young Patriots inspired small but active groups like Rising Up Angry and White Lightning in the 1970s and the John Brown Gun Club and Rednecks for Black Lives today. These days, Thurman directs the North Alabama School for Organizers in partnership with Indigenous, Hispanic and Asian activists groups. Like the Young Patriots, they do community outreach: food banks, a free automotive clinic and a construction coalition that helps build shelters for the unhoused and make homes more accessible for people with mobility issues. Thurman does not see anti-racism as a separate issue but rather as a foundational component of this kind of activism. “What I talk to people about is, if they want to organize, then they really have to understand their racism,” Thurman said. “I don’t think white people’s going to lead a revolution, but I think that we have to do every damn thing that we can to support people of color that would be leading it.”

Though Thurman and others have quietly continued the journey they started in the ’60s, more prominent groups that describe themselves as leftist may have unwittingly adopted the fractured approach once exploited by COINTELPRO agents. Modern progressives concentrate almost exclusively on issues of race and scarcely at all on issues of class. This approach strives to elevate Black and brown people to the status of middle-class white people without changing the pyramid-shaped social structure that requires some group to occupy the bottom tier of society. It’s the old joke about a plate of 10 cookies: The oligarch takes nine and tells a person of one race, “I think that other race is trying to take your cookie.” Well-meaning activists spend their time fighting over which race gets one cookie instead of fighting for more, which means that white people have two choices: voluntarily give up their place in the hierarchy in an act of selfless charity, or fight to keep it all to themselves. Neither position puts white people in actual solidarity with Black people. They can only be saviors or oppressors. Both roles assume white superiority. Neither addresses the actual causes of racism.

In practice, this neutered form of activism results in things like affirmative action, which makes it easier for some disadvantaged Black and brown students to gain admission to college at what many poor and middle-class white and Asian students view as their expense. Meanwhile, legacy admissions, mostly of white, wealthy students, continue unchallenged, and the root causes of academic disparities are never addressed. Schools in Black neighborhoods remain underfunded and employ less-qualified teachers. Racial bias within the American legal system still tears Black families apart. These factors are often invisible to the working- and middle-class white students who feel robbed of their spot in college and often direct their resentment at minorities instead of the system that offers so few chances at upward mobility.

The resulting culture war is very convenient for the top 1% of Americans, who, as of 2021, now own nearly as much wealth as the bottom 90% combined. It is also very convenient for successful white liberals, who would like to feel good about themselves without losing their spot in the hierarchy. Anti-racism without class consideration leads to symbolic gestures that change nothing, as when Democrats responded to the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests by declaring Juneteenth a holiday while leaving qualified immunity for police intact. It also provides a ready-made excuse for dismissing the plight of poor white people and instead casting them as backward, ignorant and fundamentally racist. This mindset has allowed Trump to falsely present himself as a working-class alternative to the snobbish coastal elite.

Harris, in contrast, decided to pick a man with a genuine understanding of the white working class as her running mate: Tim Walz. This suggests she is serious about retaking that ground from Trump. A Midwestern social studies teacher, veteran and gun owner, Walz advocates for progressive policy in terms that Middle America can relate to: social safety nets as “neighborliness”; LGBTQ+ rights as “minding your own damn business.”

Harris is campaigning heavily in the Rust Belt and her genuinely progressive economic platform addresses key issues faced by poor and working-class people: the sky-high cost of housing, prescription medicine and grocery prices. But Harris has also moderated her call for taxes on the wealthy and abandoned her onetime support of single-payer health care. She needs the money of the super-rich. Try as they might, no political party in our current system, under our current campaign finance laws, can truly place the needs of the working class first.

There is, however, a potentially powerful movement built around pushing for the interests of the working class — a movement that increasingly appeals to Democrats, Republicans and voters disgusted with the entire charade: unions. Support for unionization is higher than it’s been since the ’60s, not because unions play to the center but because their ideas are so far left that neither party can claim them.

“We’re here to come together to ready ourselves for the war against our one and only true enemy: multibillion dollar corporations and employers that refuse to give our members their fair share,” union president Shawn Fain told the United Auto Workers Union (UAW) after his fellow workers narrowly elected him in March 2023. “We’ve not yet won the rights that will fundamentally change this union and change this country. We’ve not yet won racial and economic justice in the workplace for all our members. We’ve not yet won equal pay for equal work.” Known for his “Eat the Rich” T-shirt and incendiary rhetoric, Fain is as comfortable quoting Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. as he is the Bible. Last September, he led the union in a historic three-pronged strike that wrung enormous concessions out of the “Big Three” American automakers, an achievement that experts smugly declared impossible when the monthlong strike began.

Two weeks after that strike began, I traveled to Detroit for New Lines. Biden was walking the picket line that day before Trump gave a speech several miles away. I asked workers which political visit they supported, expecting to find them to be as polarized as the rest of the country. Instead, everyone seemed vaguely annoyed by the question. They told me that the strike was simply not political. The left and right cannot agree on seemingly anything anymore — but union workers from both parties were aligned about the injustice of seeing their paychecks decrease while their work generated record profits and CEOs raked in millions. These opposing political factions did not meet in the center but in a space carved out by socialists a hundred years ago when they began unionizing in large numbers to demand some of the most American things imaginable: a living wage, reasonable working hours and pension plans. The idea that every worker deserves these things is that radicalism Thurman described, stripped of jargon and stigma and embraced by workers across the political spectrum.

On the surface, the strike had nothing to do with racial justice. And yet, workers of all races and political persuasions walked the picket line in common cause with each other, fighting for a better life for everyone — not just themselves. These kinds of shared goals can lead to deeper understanding and, perhaps, the realization that working-class people of all races have a lot more in common with each other than with the people at the top of the pyramid. This kind of solidarity won’t end racism but, as the Black Panthers and Young Patriots realized 60 years ago, it could be how we move forward as a nation.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.