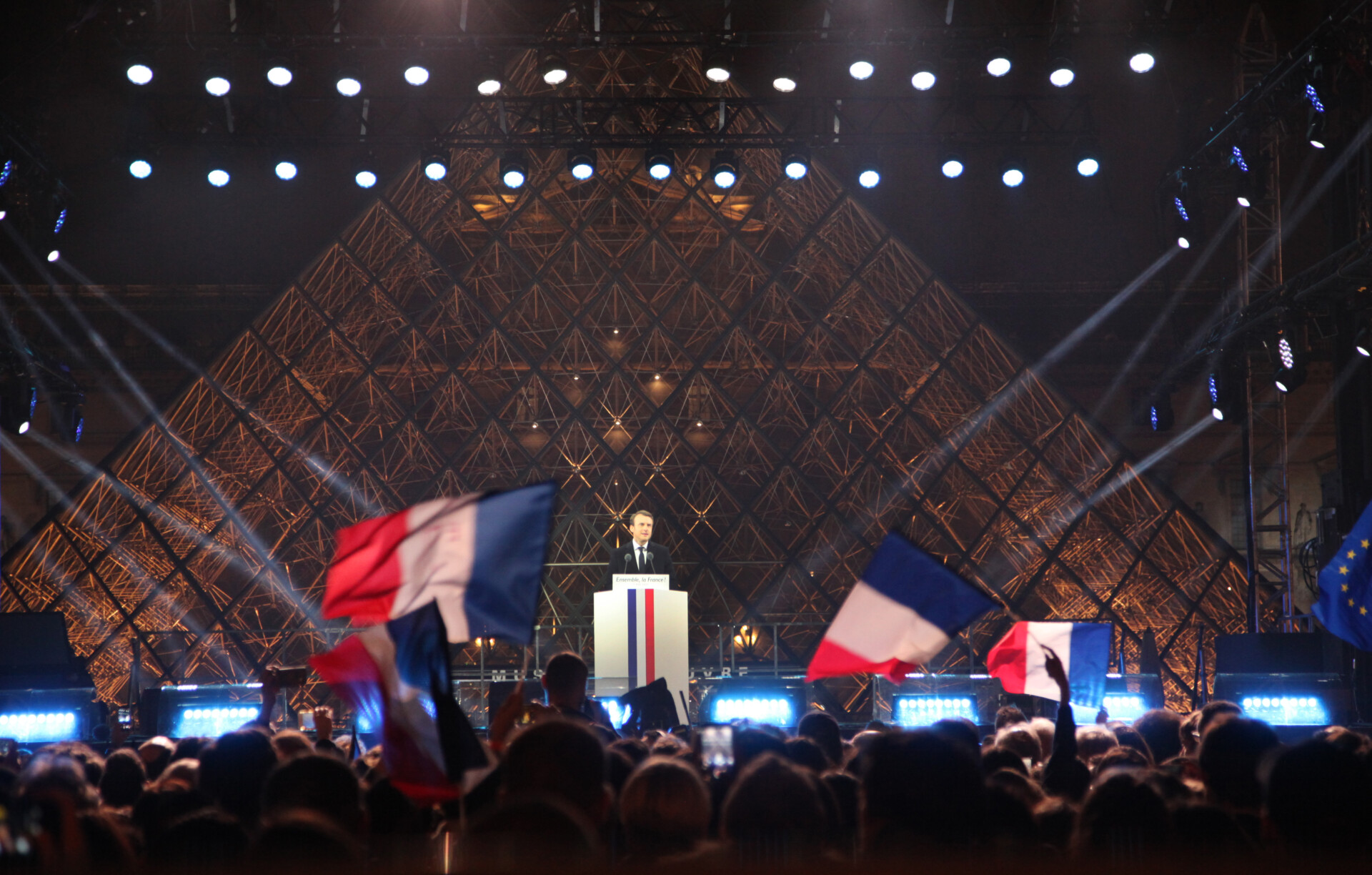

On the night of May 7, 2017, Emmanuel Macron walked alone across the vast cobblestoned courtyard of the Louvre. Floodlights traced his long silhouette beneath the pyramid’s glass panes; Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” (the anthem of the European Union) swelled in the night air. The French Republic had a new president — the youngest in its history — and he had chosen the Louvre, a palace initially built for kings and converted into a museum for the people, as the stage for his consecration.

“This place,” he told his assembled supporters and campaign crew, “belongs to the French, to France, under the eyes of the entire world.”

That night, the Louvre stood as a (somewhat heavy-handed) metaphor of endurance, civilization and France’s genius for continuity. With this coronation-like ceremony, Macron positioned himself as its custodian, the man who would preserve the splendor of the country while renewing it. I.M. Pei’s iconic glass pyramid gleamed; the republic had been safeguarded from Macron’s far-right opponent Marine Le Pen; the president posed as its modern guardian.

Eight years later, the Louvre was breached.

What happened on Sunday morning may read like a cinematic heist — a handful of masked men, a glittering loot worth over $100 million, a dash across the Seine — but the stolen jewels are not the real story. The real story is what the theft exposes: the slow vandalism by the French state of its own cultural foundations.

For years, successive governments — and Macron’s above all — have celebrated France’s heritage while quietly starving it, reducing budgets, staff, security and maintenance until the guardians of the country’s treasures could no longer guard much at all.

The Louvre break-in is not an isolated crime; it is the logical consequence of years of political neglect.

On the morning of Oct. 19, as tourists queued outside for early entry, a truck mounted with an extendable furniture lift pulled up along the Seine-side facade of the Louvre. Within moments, four masked men, dressed in work clothes and high-visibility vests, climbed the basket lift up to a third-floor window. Armed with angle grinders, they smashed through glass, shattering a window and two display cases in the ornate Apollo Gallery — home to France’s (former) crown jewels — and setting off an alarm.

According to a Ministry of Culture communique published that same day, the criminals were then “forced to flee” the gallery thanks to “the professionalism and swift intervention of Louvre staff.” The robbers escaped through the same window and quickly scaled the ladder to their truck. Museum staff were reportedly able to stop them from setting the vehicle ablaze, but didn’t manage to catch the thieves as they weaved through Sunday morning traffic on high-speed scooters with nine items from the collection in tow — one of which they dropped on the pavement in their haste.

A police source, quoted in French daily Le Figaro, said the alarm rang at 9:37 a.m. — a mere minute before the thieves sped off — suggesting that the window alarm may have failed, giving them precious time to work on the display cases before staff were ever alerted to their presence.

By midday, the museum was closed, the courtyard cordoned off, the police already combing through fingerprints and camera footage. Laurence des Cars, the museum’s director, spoke to the staff in the auditorium in the early afternoon. Her speech was poorly received by some, who booed their director and accused the museum administration of a lack of preparedness.

Among politicians, the blame game was immediate and theatrical. On X, the president of the far-right National Rally, Jordan Bardella, wondered: “Where shall the disintegration of the state stop?” The far-right commentator Rachel Khan grew tearful, saying that the expression “inestimable value” used to describe the jewels reminded her of the two French teachers murdered by Islamists in recent years, adding: “We are embroiled in a war against legacy, and against our values, and our jewels are being stolen.” On the left, Hélène Bidard, running against Culture Minister Rachida Dati for mayor of Paris, used the incident to poke fun at her opponent, who is currently under investigation for failing to declare her own expensive jewelry collection.

The chorus swelled — from left to right, across ministries, TV pundits and descendants of royal and imperial families alike — all insisting that “France has been robbed.” It has, of course, though not only of its jewels. The real risk is that this spectacular heist at the world’s most visited museum will, once again, blind us to the deeper loss it exposes.

The thieves may have escaped with eight glittering relics of empire — their stones themselves plundered from colonial Asia, Africa and South America — but the larger theft has been unfolding for years. Eight years have passed since Macron’s grandiose ceremony in the iconic courtyard. In that time, faulty alarms and failing security measures have become the norm not just in the Louvre, but in museums across the country.

Sunday’s break-in, if we look past the sparkle and the partisan circus, exposes the slow erosion of France’s state-funded culture.

The symbolism of the Apollo Gallery is impossible to miss. Louis XIV, the Sun King, commissioned it in the 1660s to embody his divine authority. The gallery survived revolutions, restorations, empires, republics and an occupation, and was then opened to the public.

By 1889, 19 years into the Third Republic, it housed France’s former royal and imperial jewels. Here, the jewels were enshrined anew, their sparkle reinterpreted as belonging to the people. When Macron staged his victory there in 2017, he tapped into that lineage: the ornate palace reimagined as a cultural center, the former royal residence converted into a republican place of power.

It’s tempting to see the Louvre as invulnerable: 30,000 works of art, 786,000 square feet, more than 10 million visitors a year, its own micro-economy of tickets, merchandising and licensing. But even that empire is built on fragile foundations.

This is not the first time a Louvre heist has shaken the country. In 1911, when the “Mona Lisa” was stolen, the press treated it as an allegory of decline. The director of France’s national museums resigned; xenophobic papers blamed Jews and foreigners. A century later, the echo is uncanny: the same outrage, the same wounded pride, the same blame game — hours after the break-in, the former Paris police chief and new Interior Minister Laurent Nuñez spoke of “experienced” burglars who could be “foreigners.” And, most importantly, there is the same refusal to look into what the theft reveals.

Then, as now, the Louvre’s vulnerability mirrored that of the state.

Des Cars has spent months warning of “an alarming level of obsolescence” and “degraded buildings.” Leaked pages from a confidential report by the Cour des Comptes, France’s national audit office, soon to be published, warn of “persistent and considerable delays in the modernization of safety and technical infrastructure.” Only a fraction of the Louvre’s galleries are under full video surveillance, and only 138 new cameras have been set up in the past five years. In the museum’s Denon wing, which is home to both the Apollo Gallery and the “Mona Lisa,” only a third of rooms are protected by video cameras.

A source within the Louvre’s workers’ union, who requested anonymity, also told the AFP that 200 full-time jobs out of 2,000 were cut in the last 15 years — notably in security. According to a Louvre employee quoted in Le Monde, only five security guards are posted in the Apollo Gallery, instead of the six of previous years — and only four during the morning break, which is precisely when the thieves broke in.

The museum declined to comment.

In the statement it gave on Sunday, the Culture Solidarity branch of the progressive Democratic United Solidarity (SUD) trade union group recalled that it has repeatedly denounced internal decisions that ignore the primary mission of the establishment: “The preservation of heritage, the building, the collections and the people.” They add that “the responsibility of the management is overwhelming, and it is high time that the president of the republic and the minister of culture take into consideration the alerts issued by the staff.”

This heist is not an isolated event. In September 2025, thieves used a blowtorch to break into Paris’ Natural History Museum and stole gold nuggets worth nearly $700,000 from the mineralogy gallery. Earlier that month, two Chinese dishes from the 14th and 15th centuries and a vase, worth over $7.7 million, were stolen from the Adrien Dubouché museum of porcelain in Limoges. After a 2024 violent break-in at a museum of sacred art in eastern France, in which some 20 visitors and security guards were held at gunpoint, many small museums in that part of France decided to display only copies.

“Museums are vulnerable and they have become targets,” Culture Minister Dati warned in a television interview on Sunday. The Interior Ministry has since asked local officials to review security measures deployed around cultural establishments in their districts, and to strengthen them where necessary.

As the political class erupted in ritualized lamentation over the Louvre heist, very few mentioned the budget cuts that gutted the very institutions they now wept over. As it so often does, the outrage avoided accountability.

For a while, after Macron first came to power in 2017, the world of culture had dared to hope. The young president was, after all, a former assistant to philosopher Paul Ricœur, a theater enthusiast fond of quoting the French poet René Char or the author André Gide, and a regular visitor at the Pompidou art center who had celebrated his elections at the heart of the Louvre. Weeks in, he’d even appointed a former publisher, Françoise Nyssen, to the Ministry of Culture, and vowed to return looted cultural objects to their countries of origin.

But optimism faded quickly.

In 2024, under Dati, funding for major national institutions fell sharply: $6.9 million was cut from the Paris Opera, $5.8 million from the Comedie-Francaise state theater and $3.5 million from the Louvre itself. The museum preemptively raised its ticket price from $20 to $25.50 to plug the hole. So much for the “democratization of culture” Macron once vaunted.

When unionized workers at the Louvre went on strike last June to protest unsafe conditions and chronic understaffing, their warnings were left unheeded. Sunday’s theft proved them right.

“The collections aren’t safe and neither are the staff,” Yvan Navarro, a member of the left-wing General Confederation of Labor (CGT) union, explained on France Info this week.

This heist lands amid the harshest contraction of France’s cultural budget in decades. The latest proposed budget (which led to the fall of former Prime Minister François Bayrou in September) cut roughly $174 million in government funding from the Ministry of Culture, while local councils — historically the main lifeline of France’s arts and cultural institutions — lost $2.5 billion in state subsidies.

In an unusually sharp statement, the Beaux-Arts Academy condemned the “violent unilateral decisions taken without consultation or transparency by several local authorities,” warning that such austerity would devastate festivals, theaters and museums alike.

At the Louvre, the consequences are visible: peeling paint, flickering lights and security systems still awaiting modernization plans drafted in 2019.

Meanwhile, in July 2024, the Louvre hosted a lavish Olympic-week gala dinner for around 500 guests, including heads of state and luxury executives. This exercise in “gastrodiplomacy” served as yet another reminder that the museum has become a stage for spectacle even as its protective infrastructure crumbles.

When Macron returned to the museum in January to unveil his “Louvre — Nouvelle Renaissance” plan for 2031, the choreography was deliberate: standing before the “Mona Lisa,” he invoked “renewal, expansion and accessibility.” But he reiterated on Sunday that the yet-to-be-financed $800 million to $930 million megaproject will mainly focus on rebuilding the museum’s eastern wing and digging new halls beneath the courtyard.

In French communist daily L’Humanite, the CGT’s cultural spokesperson Pierre Pouénat warned that the opening of the museum to the east would create “a direct gateway between this national museum and nearby shops” and private institutions — namely La Samaritaine, the luxury department store owned by Bernard Arnault, the head of LVMH, and the Bourse de Commerce, owned by billionaire François Pinault.

“These major projects are absurd, and the presidential announcements are out of touch,” said Élise Muller, national secretary of the SUD culture union and an employee at the Louvre. “The urgent need,” she said, “is the roofs, the toilets, and the lighting. The collections are in danger.”

It is difficult to recall, now, the optimism of that May 2017 night. Macron’s solitary walk to Beethoven’s anthem was meant as a moral tableau: a young reformer stepping into the long arc of French grandeur, reconciling past and future beneath the glass pyramid at the heart of the ancestral palace. Eight years later, that same pyramid stands behind police barriers. The Louvre is no longer the emblem of continuity he once invoked; it is the mirror of state fragility.

The theft will dominate headlines for weeks. There will be debates about organized crime, about the art market, about the international trafficking of stolen jewels. Eventually, perhaps, some pieces will be recovered, just as the “Mona Lisa” was in 1913. But the larger loss will remain: the slow erosion of culture as a public good that once defined France.

In seven minutes, the thieves exposed what years of complacency concealed: a country that confuses ceremony with stewardship, prestige with protection.

The jewels may yet be recovered; the headlines will move on. But the greater robbery is chronic, bureaucratic and ongoing — a slow expropriation of the public sphere in favor of spectacle. The cultural state that once anchored French identity has been dismantled piece by piece, budget line by budget line.

When Macron strode through the Louvre courtyard in 2017, he promised a new Renaissance. In 2025, all that remains is the echo of that walk — and the hollow sound of a window alarm that has yet to be fixed.

The Louvre has not simply been robbed. It has been abandoned.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.