In October 1907, the African-American sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois received a black-and-white photograph printed on a single sheet of paper. The image had been sent by the Anti-Imperialist League, an activist group then campaigning against the U.S. occupation of the Philippines. It had been almost a decade since the U.S. assumed control over the islands, following the Spanish-American War. Yet the occupation remained a deeply contested issue at home. Du Bois was himself thinking about how to effect social change and racial equality through visual communication, and the image, when he received it, stirred something.

“I think that picture is the most illuminating thing I have ever seen,” Du Bois wrote. “I want especially to have it framed and put upon the walls of my recitation room to impress upon the students what wars and especially Wars of Conquest really mean.”

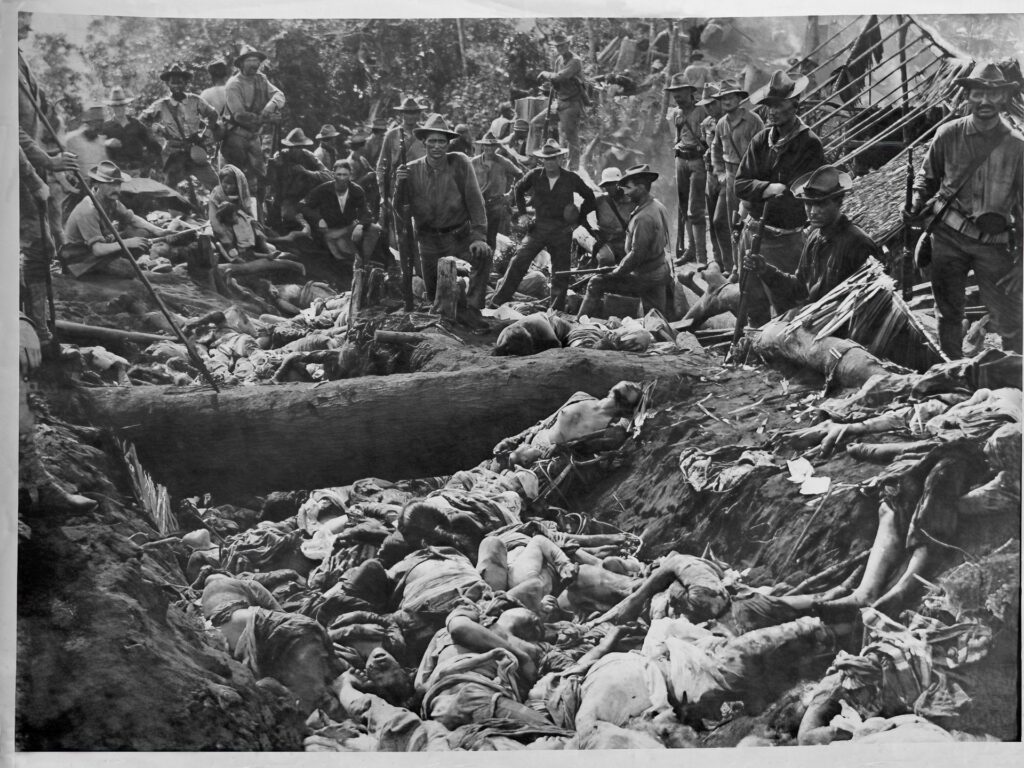

At first glance, the sepia-toned photograph shows merely a grim battlefield with soldiers wearing slouch hats, standing and sitting around what appears to be a ditch bridged by a heavy tree trunk. The ground is littered with debris, while a collapsed hut is visible on the right. In the background, rising smoke half obscures the outline of the jungle.

But a closer look shows something much darker.

Halfway out of the ditch, the unmistakable form of a woman’s body, head thrown back as if in agony, can be made out. Her right breast is exposed, and a swaddled infant is lying by her side, the small head resting in her lap. Both are clearly dead. Arms and legs and faces emerge from the shapeless piles in the foreground of the image. Yet it still takes a few moments for the viewer to realize that the trench is overflowing with dead bodies and that the “debris” is in fact corpses scattered like rag dolls over the ground among the soldiers.

Taken on the morning of March 8, 1906, the image shows the aftermath of a U.S. military assault on the eastern trail of Bud Dajo, an extinct volcano on the island of Jolo in the southern Philippines. The soldiers are American, of the 6th and 19th Infantry, and the dead are Moros, a Muslim ethnic group locally known as Tausug. It was the third day of fighting, and the last Moro stronghold, on the edge of the crater, had only just been captured.

While the Moros were armed with knives, spears, a few outdated guns and black-powder cannons, the U.S. forces were able to deploy mountain artillery, machine guns, repeating rifles and revolvers loaded with expanding bullets. At least a thousand Moro men, women and children were killed, leaving little more than a dozen survivors. Reported U.S. casualties amounted to just 21 dead and 73 wounded.

In the photograph, there is something deeply incongruous and disconcerting about the apparent ease of the exhausted soldiers resting among the torn and twisted bodies of the dead. Most of the men are looking directly at the camera, yet they betray no emotions — the proximity of death does not seem to concern them. Like hunters after a successful shoot, they are posing for the camera with the dead Moros as if they were trophies.

While the soldiers are leaning on their modern rifles, the dead appear unarmed. One soldier on the left is holding a long spear, taken from the Moros. The photograph is just another memento of what became known to the public as the Battle of Bud Dajo. The soldiers pilfered belongings from the dead, looking for exotic artifacts. Weeks later, when the bodies had decomposed, they would return to the site and collect the skulls of the Moros as souvenirs. Yet the photo that Du Bois received would prove to be the most enduring physical reminder of what had happened at Bud Dajo.

We usually think of atrocity photography as an effort by journalists or humanitarian workers to document violence and suffering or as an ethical act aimed at raising awareness and mobilizing intervention. But what about those images produced by perpetrators themselves — not to record an atrocity but to celebrate its violence? Twenty years after the pictures of prisoner abuse in Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were first released, we still struggle with how to deal with “trophy” photographs that force us to see atrocities through the eyes of their perpetrators.

The photograph that Du Bois received, which showed the massacre of Moros by U.S. soldiers, was an early example of this type of macabre celebration, made possible by the gradual profusion of camera technology around the world.

By the early 20th century, small and relatively cheap film cameras were already commonplace. But the photograph at Bud Dajo was taken with an older and heavier type of camera that used a glass plate to capture the negative. Since the exposure time was several seconds, such a camera had to be carefully positioned on a tripod, while the object had to remain absolutely still. This resulted in more composed and stilted images, where any movement would result in a blur — as can be seen in the figures in the background of the photograph.

At Bud Dajo, the photographer decided to set up their camera in the middle of the carnage and ask the battle-worn soldiers to face the device and remain still while he captured the grisly scene. This was not a spontaneous snapshot taken in the heat of battle. It was a carefully staged tableau, preserved for posterity only after significant effort. And yet such imagery was already far from rare. Indeed, Bud Dajo was not the first time U.S. troops triumphantly photographed the people they killed.

The earliest battlefield photography in the U.S. showed the corpses of soldiers killed during the Civil War. These photos were used as tragic symbols of national sacrifice, often posed artfully and in a respectful manner. None of the empathy elicited by these images, however, was to be found in the photographs of non-white people who got in the way of America’s relentless territorial expansion and the pursuit of its so-called Manifest Destiny.

On Dec. 29, 1890, the U.S. military attempted to disarm a small band of half-frozen Lakota Indians who had fled their reservation in South Dakota. When a gun went off, the U.S. cavalry began shooting indiscriminately at the Lakota who were crowded together, while artillery on the surrounding high ground opened fire on their camp. In the ensuing slaughter, which later became infamous as the Wounded Knee Massacre, almost 300 men, women and children were killed, many of them hunted down by mounted troops who pursued the survivors for miles across the snow-covered prairie.

The presence of dozens of journalists and photographers immediately turned Wounded Knee into a major media event, and the stark photographs of half-naked corpses frozen stiff in grotesque poses were widely reproduced and distributed in the form of postcards and newspaper illustrations. Since the photographic evidence showed only the sordid aftermath of the massacre, it was left to illustrators like Frederic Remington to reimagine Wounded Knee as a pitched battle in which the only casualties were implausibly shown to be the U.S. cavalry. Similar to Bud Dajo, the label of “battle” was used to mask the one-sided butchery of this massacre, which is usually considered as marking the end of the “Indian Wars.”

Almost a decade later, when U.S. military forces first occupied the Philippines following the brief war with Spain in 1898, the camera was again deployed to survey and document the new colonial subjects, and to sell the imperialist project to the American public.

Photography became as indispensable a tool of empire as the telegraph, railway or machine gun. While many of the images sent home from the war were ethnographic in style, the battles with poorly armed Filipino insurrectos, or insurgents, proved particularly popular and were printed as stereographs that could be viewed with a stereoscope to produce a three-dimensional effect. Notably, none of the imagery to emerge from the Philippines showed American casualties. Instead, U.S. soldiers were included in battle scenes exclusively as victors, often showing troops standing alongside trenches full of dead insurrectos, much as they do in the photo from Bud Dajo.

This style of celebration of slaughter through the camera lens also manifested domestically. In the U.S., the visual juxtaposition of living white bodies and lifeless Black bodies found its most horrific expression in the genre of lynching photography. The brutal torture and murder of countless Black men by white vigilantes in the American South, of which there were more than 60 reported instances in 1906 alone, usually drew large crowds of spectators. But they also attracted entrepreneurial photographers, whose grim images of dehumanized bodies were sold as souvenir postcards.

During the first decade of the 20th century, photography thus played a crucial role in disseminating the message of violence that underwrote American assertions of white supremacy at home, and celebrated imperialism and military victory abroad. The same racialized logic that enabled U.S. soldiers to slaughter Moro men, women and children at Bud Dajo without compunction, also allowed them to subsequently photograph the corpses like trophies — something that would have been inconceivable had they been white.

The image of the trench at Bud Dajo not only documented an atrocity but was also a logical extension of the violence itself. Crucially, it turned the events of March 1906, on a remote island in a far-flung corner of the empire, into a spectacle that could be consumed from the safe distance of the American homeland.

News of the Battle of Bud Dajo reached the U.S. long before the photograph did. While a cablegram from Manila could cross the Pacific — with relays through Guam and Hawaii — and reach the U.S. mainland in a matter of minutes, a photograph would have to be sent by mail onboard a ship that took about a month to cover the same route. The initial reports were short on details but described the crushing defeat of what were referred to as “Moro outlaws” by heroic American soldiers.

The disparity in casualties was seen as a tribute to the military commanders and indisputable proof of American soldiers’ skill and bravery.

“No one can read of that valorous fight,” the editorial of one newspaper proclaimed, “without a thrill of pride in the boys of the United States Army, who scaled the almost perpendicular crags and wiped out the incensed heathen from the face of Christendom.” President Theodore Roosevelt personally sent a message to Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, military governor of Mindanao, who had ordered the assault, writing, “I congratulate you and the officers and men of your command upon the brilliant feat of arms wherein you and they so well upheld the honor of the American flag.”

As more details emerged, including descriptions of the indiscriminate slaughter of women and children, there were some critical voices. The famous humorist and writer Mark Twain, who was a long-standing critic of the U.S. occupation of the Philippines, wrote a scathing critique in response to Roosevelt’s telegram. “He knew perfectly well that our uniformed assassins had not upheld the honor of the American flag,” Twain wrote, “but had done as they have been doing continuously for eight years in the Philippines — that is to say, they had dishonored it.”

The criticism and moral outrage mobilized by anti-imperialists, however, could not be sustained in the long run. The Roosevelt administration eventually managed to bury the story of the massacre on a remote volcano in the Philippines. Having dominated the headlines in the U.S. for several weeks, Bud Dajo soon faded from the public eye. By the time San Francisco was hit by a major earthquake on April 18, 1906, instantly becoming the dominant news story, distant events in the Philippines were already forgotten.

It was at this point that Wood and the military authorities were first made aware of the existence of the photograph from Bud Dajo. A U.S. official in Manila reported:

I have just ascertained that a school-teacher named Miller, now in Japan on leave, has a photograph in his possession of the Dajo fight, in which is shown a half-naked female corpse, with a gash in the breast, and lying near the bodies of several infants. American soldiers are standing near, gazing at them, and due to light and shade the female corpse looks like that of a white woman. Miller has shown the picture to several people and boasted that he intended to sell it (of course at a long figure) for use in the next Presidential campaign. His remarks on the subject of the fight have not been complementary [sic] to our people, and he claims that it was a massacre.

Evidently, the real concern over the image was not the violence it depicted as much as the fact that the dead Moro woman at its center might be mistaken for a white woman. While the massacre of Indigenous people was considered justified, a racial “misreading” of such an image would be damaging to both Wood and his supporters, including Roosevelt. Wood’s staff also noted that another copy was said to be in the hands of a soldier and suggested that efforts should be made to intercept the images: “It may be possible to destroy them.”

Despite their best efforts, the authorities failed to prevent the image from reaching the American public. When the photograph was eventually published on June 23, 1906, in the popular magazine Harper’s Weekly, however, there was no outcry whatsoever. A slightly cropped version of the image of the trench was reproduced together with another photograph of a wounded American soldier being transported on a mule following the assault. Beneath the two images, the caption read, “The Fight on Mount Dajo,” followed by a brief account:

The photographs on this page picture scenes connected with the battle between Moro outlaws on Mount Dajo, on the island of Jolo, and the American troops, early last March, when, in the face of almost insurmountable difficulties, the Americans exterminated the band of 600 savages who had made themselves a menace to the island. Mount Dajo is extremely steep and rugged, the last 500 feet of the ascent having an angle of from 50 to 60 degrees, and the last 50 feet being practically perpendicular. The outlaws were strongly fortified, and it was up to a veritable death-trap that the Government troops had to fight their way. Twenty of the Americans were killed and twenty-five wounded.

The use of the term “outlaw” to describe the Moros entrenched on Bud Dajo, including the women and children, deprived their resistance of any political legitimacy and reduced the conflict to a matter of law and order. Rather than the barely human forms of the dead Moros, it was the American soldiers who were presented as the real victims of Bud Dajo, and for whom the reader’s empathy was intended. The general belief in American exceptionalism and the implicit righteousness of “benevolent assimilation,” as the civilizing mission in the Philippines was called, thus remained strong. Instead of being a source of shame, the Battle of Bud Dajo was in fact celebrated within the U.S. Army, and three of the officers who had participated in the assault were later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Du Bois’ belief in the efficacy of the photograph as a means of raising awareness and mobilizing public outrage was commonplace at the beginning of the 20th century, much as it is today. The camera was thought to provide an incorruptible representation of reality, and it was, as such, well-suited to expose the true state of the world — whether that be the brutality of slavery, the squalid living conditions of the poor or the horrors of imperialism in Africa.

Photographs of the mutilated victims of the Belgian King Leopold’s brutal regime in Congo, for instance, were widely distributed by his critics, in pamphlets and other publications, and even shown at public meetings using magic lantern projectors. Just a few years earlier, Twain had written a searing satire, “King Leopold’s Soliloquy,” in which he imagined Leopold describing the camera — “that trivial little kodak, that a child can carry in its pocket” as “the only witness … I couldn’t bribe.”

The Anti-Imperialist League had in fact sought to achieve something similar with the photo from Bud Dajo, and hundreds of copies were printed and mailed directly to members of the U.S. Senate, as well as to Du Bois. However, their faith in the power of the image turned out to be misplaced. Despite their efforts, the campaign failed to elicit any public outcry. Instead, the photograph was turned into a postcard, much like the ones from Wounded Knee or the Philippine-American War, and the spectacle of the massacre reduced to a colonial commodity.

In the end, even Du Bois never found out what the story behind the photograph was, and he never got a copy to hang in his office. Unlike the My Lai Massacre in 1968 during the Vietnam War or the use of torture at Abu Ghraib, what happened at Bud Dajo failed to become a historic touchstone. Despite the graphic evidence of this atrocity, few people outside the Philippines today are aware that it even took place.

In her final published essay, Susan Sontag reflected on the power of the photos from Abu Ghraib, which she saw as a visual antidote to the insidious euphemisms of the war on terror. Crucially, she also recognized these digital souvenirs as the modern-day equivalent of the monochrome photographs produced of lynchings in the American South, with their grim juxtaposition of Black victims and gleeful white spectators. The distance between the past and the present seems indeed to fade in the staged triumphalism of trophy photos. The fact is that we have seen it all before — at Bud Dajo, in Iraq and Afghanistan or, at this very moment, in Gaza.

At a time when we are inundated with images of suffering, the problem is not that we have looked at too many photos but that we haven’t looked closely enough. If the act of bearing witness is to be more than a cliche, we cannot afford to look away. More importantly, we must also have the courage to recognize what it is that we see.

In a trophy photo, there is no room for the passive tense; it is only too obvious who is doing what and to whom. A trophy photo is never an image of a “tragedy.” And so, when perpetrators show us who they are, we ought to pay attention. In the past as much as the present, atrocities are not simply constituted by physical acts of violence but also by the way they are legitimized, covered up or deliberately forgotten. If we cannot prevent atrocities, we can at least make them more difficult to justify. By insisting on truth, we can make it that much harder to commit a massacre and call it a “battle.”

One thousand miles away or 100 years ago, the moral obligation not to avert our eyes from the pain of others thus remains the same. We are not responsible for the past and we cannot change it. But we are responsible for our actions today, as well as for what we choose to see or ignore. History is not simply something to look back on but something to confront and to act upon. That was true more than a century ago at Bud Dajo and it is true today, as a steady drumbeat of images of dead and wounded from Gaza continues to reach the world. The purpose of this story is not to say, “Look what they did then,” but rather, as the film director Jonathan Glazer has said, “Look what we do now.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.