A few weeks ago, while glued to my screen, I came across a curious TikTok from Nas Daily, the handle of Nuseir Yassin, the YouTuber-turned-travel-influencer with a following in the tens of millions, known for his daily one-minute videos of his adventures across the globe. Nas, as he goes by, recently uploaded a video in Papua New Guinea, claiming he was with the world’s “scariest tribe.” Behind him, a group of men from the Asaro tribe, wearing traditional mud masks, swayed back and forth, feigning intimidation for the prospective onlookers. As Nas gesticulated in front of his animated background, graphic text took over the screen: “What IS This?”

I have recently noticed a rise in these types of videos on social media. A travel influencer in an unidentified region of Papua New Guinea stands in the foreground, explaining the cultural customs of a specific tribe, as some of its members fill in the background. A scroll through Instagram will produce recurring images of the Skeleton Tribe, Asaro Mudmen or Spirit Birds, the groups linked by their aesthetic novelty. The more startling their appearance, the more desirable they are to document. An influencer narrates while the members of the tribe move with faux intimidation in the background, shouting or screaming in a way that feels directed. This composition always feels considered, a dynamic that suggests our guides into this culture are rendering the “otherworldly” intelligible.

In recent years, content that veers toward the more extreme has become the norm. A study by the data analytics company Demand Sage found that over 207 million individuals identify as influencers, indicating just how saturated the creator economy has become. To stand out, more and more creators are turning to stunts or shock content — being buried alive for a week and filming the entire ordeal, scaling the world’s tallest buildings without harnesses or ropes, interviewing a celebrity while eating chicken wings soaked in hot sauce so spicy it can cause gastric distress — and are rewarded by the algorithm.

In their corner of the internet, travel influencers have seen an uptick in engagement as they’ve begun entering more extreme and remote pockets of culture for their channels. Whether videos consist of tribe members doing “fit checks” with model influencers, or creators becoming self-appointed reporters within remote tribes, or simplified, omnipresent voice-overs attempting to explain extreme cultural customs, an ecosystem of exoticism has sprung to life online.

Buried within this realm of exotic tourism, one individual invites followers to explore beyond the screen. The collector, museum owner and artist Viktor Wynd has started offering a series of expeditions, which he calls “Gone With the Wynd,” aimed at those with a penchant for curiosity, looking to get off the beaten track. Priced at around $4,500, Wynd offers a 10-day excursion to the remote depths of Papua New Guinea, traveling more than 100 miles by boat to spend time with the Asmat people. This group, known for their history of cannibalism, was the subject of devoted study by the explorer and collector Michael Rockefeller and its members are, according to Wynd, “perhaps the most famed wood-carvers and artists of the Pacific.” Wynd’s itineraries promise a culturally immersive experience in the supposedly untouched north of New Guinea, including the chance to buy and collect objects. The schedule for the sold-out trip, which is due to take place this October, has a set of images pinned at the bottom, showing an all-white group of travelers walking in a port in New Guinea, woodworks in tow.

With the words of Nas Daily ringing in my head, I too wondered, “What is this?” This bizarre rise in remote tourism and field trips to collect “exotic” goods feels reminiscent of the 17th-, 18th- and 19th-century European phenomenon of collecting and presenting curiosities of all sorts from overseas as a way to demonstrate one’s worldliness. Whether accruing images or objects, where has this return to collecting come from? And what does this desire to possess the “obscure” say about those who seek to do it, and the narratives they create?

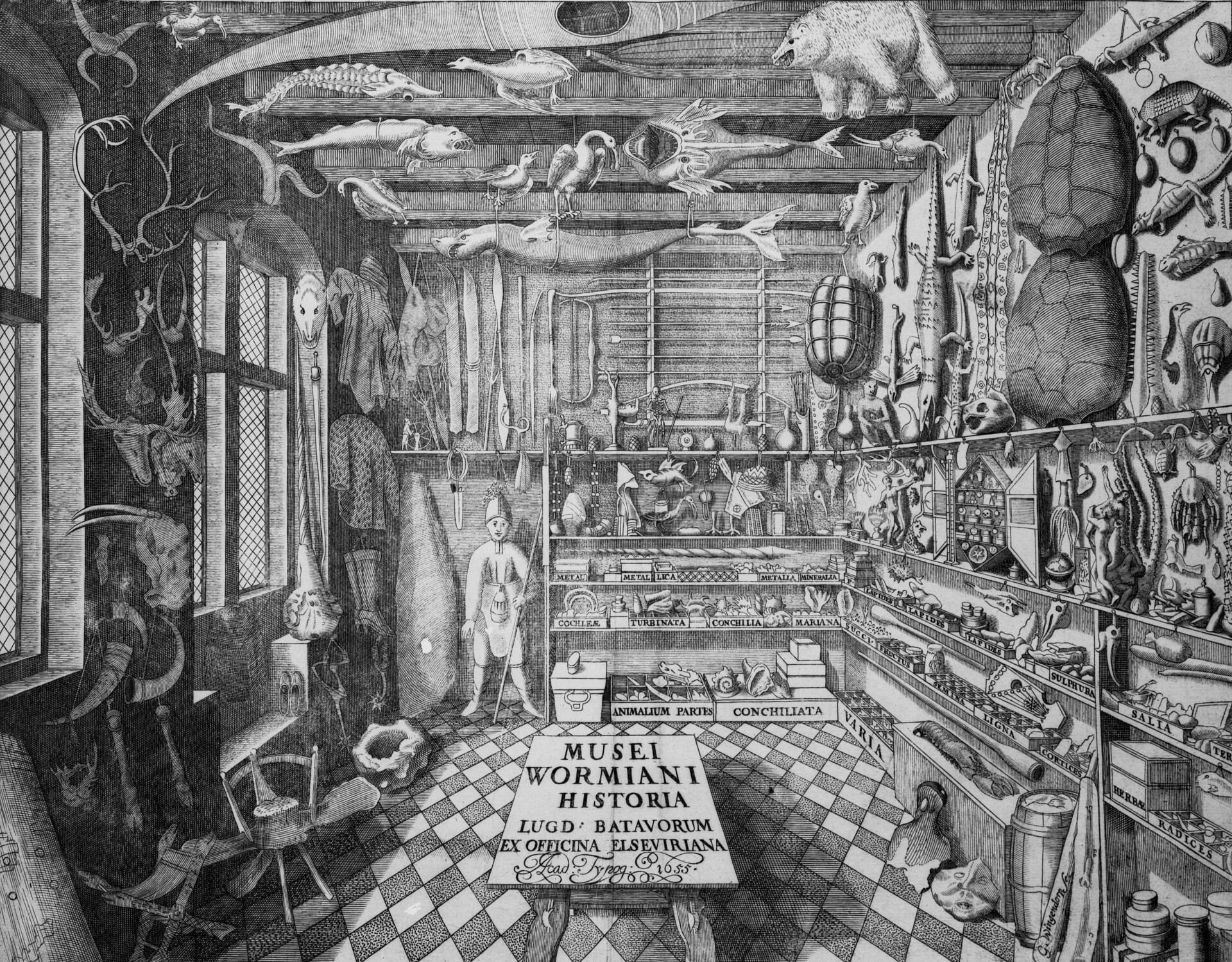

From the mid-16th century onward, an age of discovery got underway in Europe, after contact was made with the Americas and travel distances expanded. The trade routes that brought gold, spices and silks to Europe also began to yield more outwardly strange objects from overseas, which were funneled into private collections. Initially reserved for the upper classes of early modern Europe, curiosity cabinets were collections of natural and cultural objects curated in terms of their allure and obscurity. From botany to bones, preserved animals to totem poles, objects were bought, traded, plundered and stolen to be carefully ordered, displayed and forced into collectors’ own frameworks of value, which shared little or nothing in common with the objects’ original use. Often, these collections acted as fictions, with objects stitched together to weave sensationalized accounts of the types of people and creatures that existed beyond European soil. Curiosity cabinets added to the folklore surrounding faraway places, with the emphasis on the “exotic” cementing a binary from which modern society has seldom escaped. For these individuals, it was less about the meaning of the objects and what they told us about the culture from which they came than the stories the cabinets told about their collectors and how they saw themselves. The more extreme, unique and beguiling, the closer one was to intelligence and power.

As the Dutch, English and French empires expanded across the globe, so too did their acquisition of foreign objects. Early aristocratic collections laid the groundwork for modern museums, though museums became structured around order and categorization over time. Like many cultural institutions around the world, the foundations of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History’s cultural wings were shaped by the upper class of a previous era. But with this modern form of presenting objects, a new era of privileged figures came to dominate the arenas of exploration, collection and curation.

In 1961, Michael Rockefeller, then the 23-year-old son of the governor of New York and scion of one of America’s wealthiest families, made two expeditions to the land of the Asmat, a region along the southern coast of New Guinea. These trips, alongside the production of research for the Harvard University-affiliated Peabody Museum, aimed to study the Asmat people and their way of life, and, according to Rockefeller’s journals, to “explore the possibilities of collecting Asmat works of art.” A history and economics graduate from Harvard, whose primary qualification to conduct such research was a verve for doing so, Rockefeller wrote in his field notes from the time: “After careful study of the large collections of Asmat things now in three Dutch museums, it would be possible to organize a mammoth exhibition which would do justice to the art of these people. … You can imagine what fun I am having dreaming these wild dreams and creating earth-shattering hypotheses about the nature of Asmat art.” Rockefeller’s fascination with how these works could be curated and displayed reflects the same worldview held by the collectors who came before him. Art from so-called “uncontacted” worlds was framed through the gaze of privileged explorers, shaped not by the cultures themselves but by the imaginations and interpretations of those who sought to collect them. The objects Rockefeller aimed to present within Western institutions were filtered through his own fantasies and “earth-shattering hypotheses,” forming a narrative defined more by the collector than the collected.

This interplay between narrative, power and possession continues in contemporary collections. A flick through Wynd’s Instagram shows a man immersed in the world of oddities, sharing images that range from sea monsters to masks worn by male dancers from the Yoruba tribe in West Africa to celebrity feces. Like Rockefeller, Wynd constructs meaning through objects, but where Rockefeller sought the formality of public institutions, Wynd leans into spectacle and story. Interspersed between pictures of his collection are images of Wynd himself — middle-aged, eccentrically dressed and noticeably posh — taken on his travels or at his farmhouse in Suffolk, England. Born in Shanghai and raised between London and western England, Wynd studied at the Sorbonne and the School of Oriental and African Studies, as well as the University of South Florida, before opening his first “Wunderkabinett” (“curiosity cabinet”) in 2006.

Over email, he explains that his passion began as a child, collecting pebbles, soldiers, toy cars — whatever he was able to get his hands on. As he grew older, so did his fascination with objects, and, once able to travel, these collections and ambitions grew larger still. He started his “Gone With the Wynd” expeditions out of a desire to make travel to remote parts of the world simpler, and to find like-minded people to “disappear into the bush” with for a couple of weeks at a time.

In Wynd’s case, the well-trodden route of Pacific goods to privileged hands repeats itself. Yet unlike many of his predecessors, he openly embraces the myths involved in collecting: “I’m looking for things that speak to me — that tell me stories — or I can tell stories to.” Perhaps this storytelling impulse softens the moral stickiness; by indulging in the constructed fictions of collecting, Wynd’s ignorance becomes performative rather than blind. His cabinet becomes a gallery layered with truths, half-truths and embellishments. But media coverage of Wynd’s collection is not limited to its contents; rather, an image of Wynd is built from the objects with which he surrounds himself. In their image, Wynd is cast as a macabre figure of mystery. “Objects are alive,” he says, or “if not alive, they definitely have their own agency and are collecting me as much as I am collecting them.”

In the case of Wynd, he seems to comprehend the fictions he’s involved with; the living mythologies that reside in his East London cabinet. But once you extend this invitation to the wider public, how does this practice move into murkier waters? In a survey conducted in 2024 by the travel organizer TripIt, 69% of Gen Z and millennial respondents said they found travel inspiration on social media. Another survey by the vacation home insurance company Schofields found that 43% of Gen Z travelers chose destinations according to their potential to accrue “likes” and “views.” With no more need for a physical space that represents our interior worlds, social media has become our online display cabinet — a living gallery in which every image becomes a vehicle of storytelling or an opportunity to say something about yourself. Nas Daily’s videos from Papua New Guinea speak to possession in a way that is more extreme than Wynd’s expeditions. Rather than objects telling the story, humans are made into objects, used as visual bait to promote someone’s brand and encourage engagement.

During Rockefeller’s 1961 expedition, he disappeared, rumored to have been killed and possibly eaten by members of the very community from whom he was acquiring objects. The symbolism feels pointed, even poetic. It echoes Wynd’s belief in the reciprocal power of objects: In seeking to possess, the collector becomes possessed. The boundary between object and owner blurs; the cabinet begins to speak not about the things within it, but about the person who assembled them.

With the Michael Rockefeller Wing at The Met closed, I make my way instead to the American Museum of Natural History, to the Pacific Peoples hall on the third floor. The space is awash with tribal music, and the display cabinets in blues, yellows and greens frame objects from across Polynesia and Micronesia. In one box labeled “The Asmat People,” small printed tags identify a basket-tree pig headdress, several masks, a gourd jar, an ominous ceramic face emerging from a speared bouquet and a 6-foot shield. About a hundred words accompany each cabinet, barely enough to describe a people, let alone explain the lives of the objects themselves. It would be easy to dismiss this as colonial residue, but doing so risks overlooking the complexities of cultural exchange. Still, something feels off. The immersive soundtrack, the theatrical lighting and the careful arrangement of artifacts are meant to transport us to distant lands, but instead conjure a simulation, a fantasy of an untouched, petrified culture.

In the long hallway of Pacific ephemera, I stop in front of a large mask staring back at me from beneath a gold-embossed label: “New Guinea.” A single title meant to encompass an entire region, its peoples, their rituals, their aesthetics — flattened into one unblinking face. A snapshot of difference, framed by the familiar logic of classification. It’s a reminder that collecting, at its core, has always been about storytelling. And more often than not, the story being told is not about the objects themselves, but the people who choose to keep them.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.