In an unexpected gesture of kindness, Daniella, my Airbnb hostess, invited me for coffee in her cozy kitchen. In early November, I booked a room in her Tel Aviv house and flew to Israel from my home in Brussels. The awkwardness that often hovers over first meetings vanished when we realized we were both mothers to young girls — mine 15 months old and hers a little over 2 years. As we discussed the joys and travails of motherhood, her daughter, asleep on the first floor, let out an urgent cry to summon her mother. Daniella sprang up from the chair and ran to soothe her.

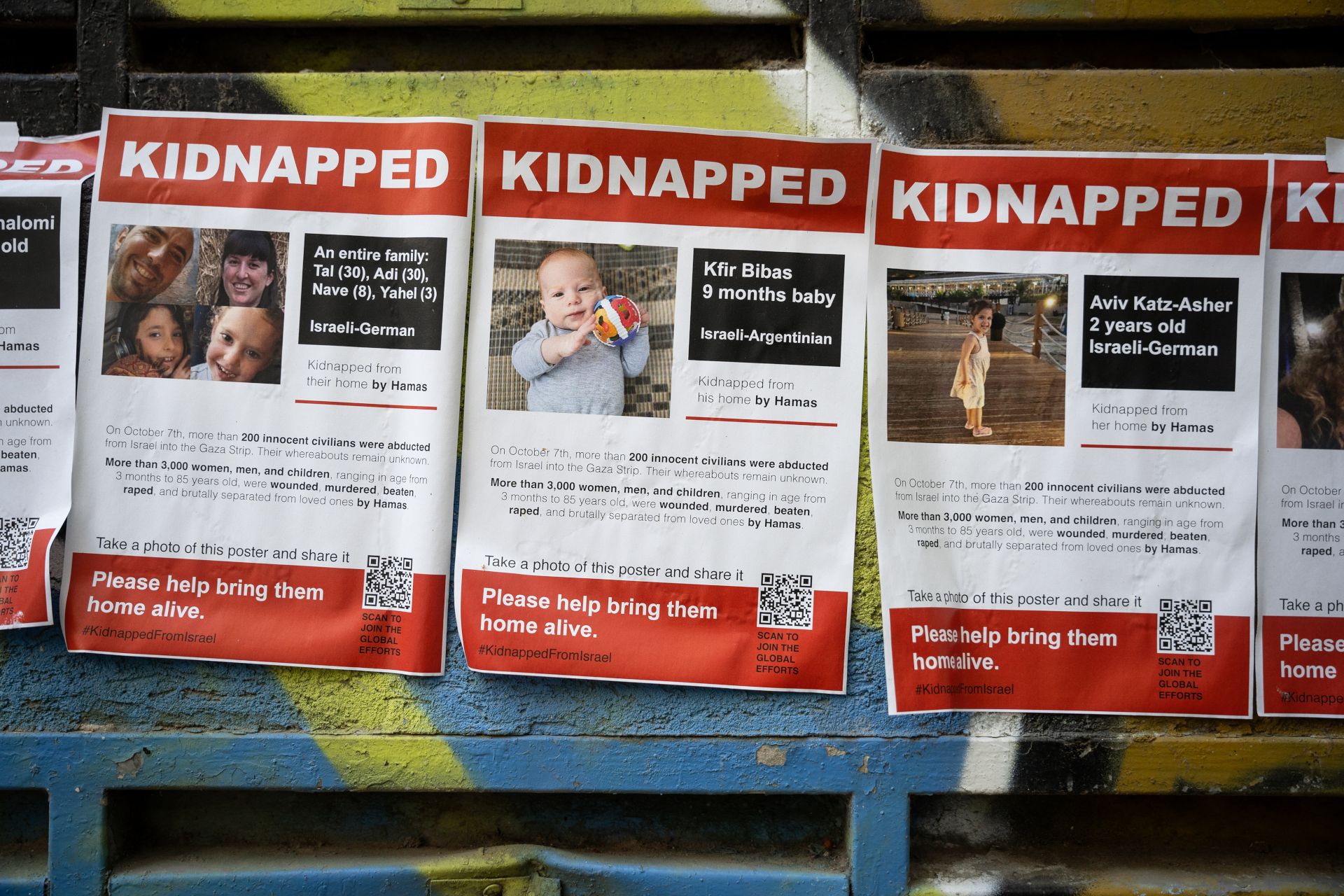

Outside Daniella’s home, posters of children held hostage by Hamas, in some cases with their parents and in others separated from them, were plastered on the walls. The photo of ginger-haired Kfir Bibas, taken hostage at 9 months, showed him holding a pink soft toy in his hands, while the smiling faces of Avigail Idan and Raz Katz Asher, both 4 years old, peeped out of other posters. Ela Elyakim, 8 years old, stood with her hand on her waist and 5-year-old Emilia Aloni wore a checkered swimsuit and had tousled hair, as if just out of the water on a fun day out with her parents. The word KIDNAPPED was printed in bold font on all the posters along with the hashtag #BringThemHomeNow. The four girls have since been released in a prisoner exchange, but 132 Israelis are still being held hostage in Gaza.

A sense of insecurity was palpable in the city, even among its children, as Daniella confirmed. “My daughter hasn’t been outside the house, not even to the park,” since Hamas’ attack in southern Israel on Oct. 7. More than 1,000 Israelis were killed in the brutal attacks and more than 200 abducted by Hamas in a matter of a few hours. “Other children in the neighborhood are also terrified. They keep looking for a place to hide in case Hamas attacks again,” Daniella said, standing in the tiny space in her house between the kitchen and the reinforced room. (All Israeli residences built since 1992 must, by law, include a room that is reinforced against conventional weapons blasts and is impermeable to chemical and biological weapons; the rooms are known by the Hebrew acronym “mamad.” A bouncing chair and some toys were scattered in Daniella’s.)

Just two days earlier, Hamas fired rockets that targeted her neighborhood, further exacerbating fears of a full-blown regional war that are so prevalent among Israelis. “We are going to move back to Poland,” Daniella said, with her daughter Eden in her arms. Daniella, whose father was Polish and mother Israeli, had moved to Tel Aviv a decade ago to live a more culturally Jewish life, in a Jewish-majority city. Now she feels that quest isn’t worth the trauma imposed on her daughter. “Children should not be subjected to this,” she said.

The impact of the intractable conflict on Israeli and Palestinian children was severe even before the Oct. 7 attack and Israel’s military response but, according to child psychologists, the current conflict has intensified their trauma and left indelible scars.

What does it do to a young person’s mind when she witnesses strangers enter her safe space, her home, and kill her parents? Or to be abducted and imprisoned in a dark tunnel far below ground? And what does it do to see your parents helpless and your entire neighborhood bombed? Or, if you are not suffocating under the debris, to have no water, no home, no toilet, no medicine and no exit to a safer neighboring nation?

Eden’s routine cry shook Daniella. Her reaction was relatable. Common ailments such as colic or fever can rattle a parent. But the pain of parents whose children are being held hostage by Hamas and of those in Gaza struggling to keep their children alive as the Israeli government rains down bombs seems incomprehensible.

In a hostage deal mediated by Qatar in December, Israel agreed to release three Palestinians for each Israeli. Even today, however, more than a hundred hostages are still in Gaza, including Kfir Bibas. He turned 1 in captivity, held with his 4-year-old brother Ariel.

Ofir Engel, a 17-year-old Dutch-Israeli citizen, returned from captivity in Gaza on Nov. 29 without a scratch on his body, but the trauma he endured may not surface for years. “We don’t ask him much, and let him volunteer to share what he wants to,” said Yosef Engel, Ofir’s grandfather, over the phone. He added: “The impact could take months to show. We just want him to return to normal life and so far he seems fine.”

Psychologists say it isn’t clear whether the children are fine or are just pretending for the sake of their parents, especially since many other hostages who provided them with love and care in Gaza have still not been freed. Ofir was detained along with his girlfriend’s father, 53-year-old Yossi Sharabi. Hamas said recently that Sharabi had been killed.

Asher Ben-Arieh, a specialist in child trauma at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and at the Haruv Institute, said many younger children were finding it difficult to sleep. One of them preferred to sleep under the bed and another spoke in whispers.

Ben-Arieh was assigned the task of writing a protocol for children held hostage and those who witnessed the murder of a loved one. He said he developed nine different protocols — including for Israeli intelligence officials who first greeted the released children in Egypt and brought them back.

“We asked them (officials) not to hug the children without permission,” he said. “We need to let kids regain control over their lives, and create a sense of security and stability. Sometimes that means letting them use social media.”

He said while the children are being monitored and not being pressured into sharing more than they feel comfortable with, it was clear that they had been ill-treated and some even sexually abused. “We had cases of emotional abuse and sexual abuse, kids were drugged, beaten, kids were separated from adults,” he said, declining to elaborate.

He said his leading concern is the well-being of the children; he is worried that restoring their faith in humanity may take a long time and a lot of effort. “We tell our kids that parents will protect them, that the house is the safest place for them. I am trying to tell them again but will they trust me?”

In Gaza, the suffering is bloody, historic and far from any stage of recovery.

In 2002, Aisha was sitting in her car with her mother when a bomb blew up right outside. She was barely 9 at the time. (Aisha’s name has been changed at her request. She doesn’t want her extended family in Gaza to be identified.)

“I remember black everywhere, it was the smoke. I still remember the smell of that storm,” she recounted from her home in the U.K., where she moved with her husband. “I remember the name of the doctor, it was Dr. Saleh. Who remembers the name of a doctor in the emergency ward? I still remember my mother was wearing a mustard-color jacket. When my father picked me up from the hospital there was a body in the ambulance outside, a burnt leg was dangling. He covered my eyes,” she said, nearly breaking down.

“When I look back at myself, a 9-year-old terrified girl, I shake with fear and sadness,” she added.

Aisha’s agonizing journey continued when her abusive husband tricked her into returning to Gaza and left her there with her three children. During their time in Gaza, the children witnessed several conflicts between the Israeli military and Hamas. “My daughter lived through the same trauma. She used to ask me: Are we going to die, Mumma? There are bombs falling from the sky.” Aisha said she was the first Gazan woman to win a court case in Gaza to be able to travel alone with her children back to the U.K., at a time when women were not permitted to travel without their husbands.

But tragedy has chased her family and the ongoing war is testing all their strength and courage. “My niece, who is just 18, gave birth in a tent. She had a C-section and had a terrible infection. Five days later they finally found a functioning hospital for her. But I don’t even know if she is with her 5-day-old son. Are they together? Is she fine? Is he fine?”

Her 15-year-old nephew is struggling, too. He has not spoken since an Israeli soldier put a gun to his head and ordered his father to strip along with hundreds of other men. “The IDF soldier who held the gun to his head said, ‘You have 10 minutes to leave the neighborhood or we will shoot the boy,’ can you imagine?” she said as she burst into tears.

“My brother said they made him walk uphill and threatened to shoot him. In Arabic they said to him: ‘You will die.’ They tied his hands, blindfolded him and did not tell him whether his son was alive or dead or where his family was.”

The men were finally dropped off on a beach. From there, they walked to a camp, where they were lucky to reunite with their families. “They took whatever clothes they could find in bombed-out houses of people who had perhaps been killed or fled. Can you imagine what they must have gone through? … My nephew is shaken and my brother has grown into an old, depressed man.”

By the time this essay went to press, Aisha was unable to reach her brother to ask if he would speak to New Lines. But similar accounts have been reported in Al Jazeera and in a United Nations report released last month.

Ajith Sunghay, head of the U.N. Human Rights Office in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, said he met a number of Palestinians who had been “detained by Israeli Security Forces in unknown locations for between 30 to 55 days.” He said the Palestinians described “being beaten, humiliated, subjected to ill-treatment, and to what may amount to torture.”

Aisha’s brother and 15-year-old nephew are traumatized but there are no trauma centers in Gaza to help him. There was no one to help her.

“No one knows what’s happening inside. No one knows our stories.”

Thousands of children have died in the bombings in the current conflict and thousands more have been orphaned. According to Save The Children, a child is killed in Gaza every 15 minutes and children make up one-third of fatalities. There is no clean water, essential food items have run out and health care for children who were already sick is lacking. Over half of Gaza’s hospitals — 22 out of 36 — are nonfunctional according to the World Health Organization, and the absence of electricity has led to deaths among newborns.

The tragedy in Gaza is of such mammoth proportions that casualties there, once again, have turned into mere statistics. Foreign correspondents have mostly gained only limited access to Gaza with Israeli military embeds, so it’s hard to report accurately from the besieged territory. Local Palestinian journalists report under bombardment, risking their personal safety — as of the time of writing, 85 Palestinian journalists have been killed in Gaza — and still their coverage cannot sufficiently convey the effects of the war.

Images of children covered in mud and in their own blood, in the arms of their parents or a relative, have flooded social media, but the images are so harsh and heartbreaking that the first response of many, including me, is to scroll up quickly to avoid looking at them. I just can’t watch it, I say to myself, and then think of the parents of those children and my daughter.

The Palestinian parents feel the same helplessness as their Israeli neighbors, perhaps only more urgent as they struggle to protect their children with no technology to repel the bombs and no toolkit to mitigate their trauma.

Amal Helles introduced herself as “a journalist and a mother at the same time.” She has two children: Maryam, 6, and Waj, 4. Since the war started, Helles has been forced to move several times. There is not enough food, she said, nor electricity. “What makes it more difficult is that I am a mother and I have a duty to provide my children with some safety in light of this bitter reality. I try to create some fun atmosphere for them through drawing, coloring, acting, singing,” she said. “Sometimes I don’t say anything, I just hug them tightly because I also feel afraid.”

Helles is not alone. Juliette Touma, Director of Communications at the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), who recently returned from Gaza, said most parents are facing the same ordeal. “They say I cannot tell my child it’s going to be all right, maybe it won’t be all right. No one knows what’s going to happen from one hour to the other,” she said. The parents, above all, feel “an overwhelming sense of helplessness.”

Approximately 1.7 million people in Gaza have been forced to flee their homes, and are residing in makeshift structures. “There is a sea of these structures — two pieces of wood attached with a plastic sheet, and that has become home to the displaced masses,” she said. Thousands are taking shelter in UNRWA schools where basic amenities like a restroom are limited. “One of the women I met said: ‘I just want to wash.’”

The Rafah crossing into Egypt is the only option left for Palestinians to leave Gaza. But since the war began, the border has been opened only to evacuate foreign nationals, Gazans who have dual nationality or those who can afford the prohibitive bribe of up to $10,000 per person for permission to enter the Sinai, as well as some wounded Palestinian civilians. More than 2 million Gazans, nearly half of them children, have no place left to run to or hide. Some Israelis on the far right want Egypt to take in an unlimited number of Palestinians from Gaza, but Egypt does not want to do that, nor risk the appearance of aiding their mass displacement. There are, however, many Palestinians desperate enough to leave Gaza via the Sinai if Egypt would allow them, even though they fear that Israel would never allow them to return.

Israelis have been displaced, too. Hundreds of thousands from the communities near Gaza and from the northern border with Lebanon, which is regularly under Hezbollah bombardment, are languishing in hotels. They, too, carry the burden of transgenerational trauma — in their case, from the genocide conceived by the Nazis during World War II.

In December, Daniella moved back to Poland for the emotional well-being of her child. “Eden tells me, ‘Mum there is no boom boom here, like at home.’ She is so relaxed here, I think she doesn’t want to leave.” Daniella said she was horrified by the number of children who have been killed in Gaza: “I just hope that at the end of all this there is peace between Israel and Palestine. But I don’t think that will happen as long as the current Israeli government is in power.”

“I don’t know when we will go back. Maybe the next intifada will start in the West Bank. Maybe it will get worse,” she told me during a mid-January phone call from Warsaw.

I cut short my Israel trip and returned to my little one. She hugged me tightly for five minutes at the Brussels train station and, since then, insists on sleeping on top of me, in my arms, clutching my shirt to make sure I don’t disappear. I apologize softly for abandoning her. I think how lucky I am, how selfish, and how helpless we all are in front of bombs, national causes and hatred.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.