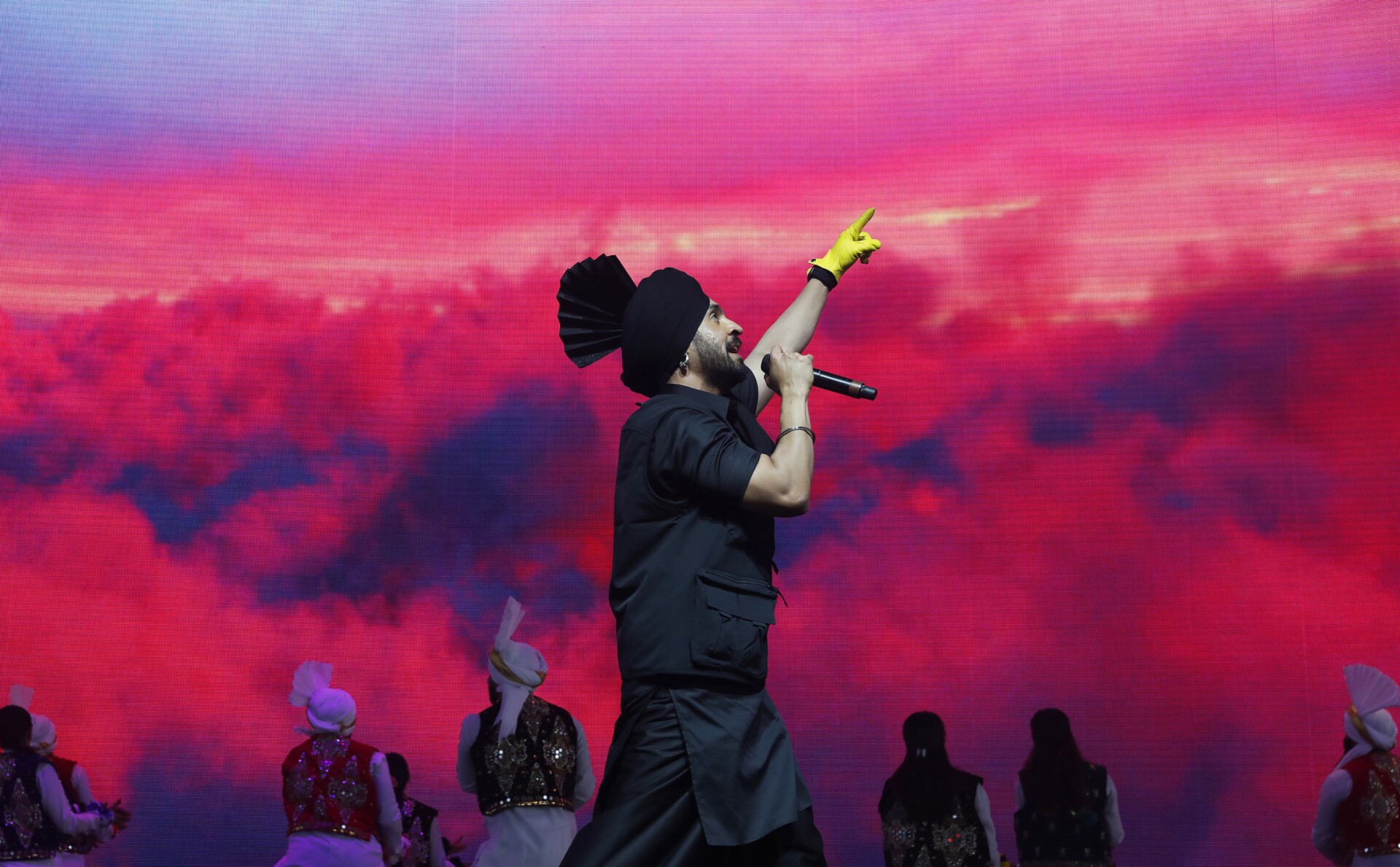

In 2023, when Diljit Dosanjh became the first Punjabi — and Indian — artist to perform at Coachella Festival, he turned up on stage in a traditional Punjabi outfit of “kurta and chadra,” with a turban. (A kurta is a knee-length, collarless shirt, while a chadra is a type of loincloth worn in the state of Punjab in northwestern India.) He paired this with a black Carhatt WIP vest, retro monochrome Air Jordans and a pair of neon yellow gloves — effortlessly fusing the traditional with streetwear. It created hysteria among Punjabis the world over, as well as Indians in general, who felt that they had arrived on a global stage as their most authentic selves. People lauded the ode to his Punjabi roots — all the more so when he announced “Punjabi aa gaye Coachella oye,” or “The Punjabis have arrived at Coachella.”

It also seemed fitting that he opened his performance with the 2020 song “G.O.A.T,” in which he flexes his popularity and achievements, from being the first Sardar (turban-wearing Sikh man) to make his mark in Bollywood to waving at crowds of excited girls from his car window and being the first Sikh celebrity to have a wax statue at Madame Tussauds. “You can search up the ‘Dosanjh’ name anywhere,” he says.

While that song entered global music charts in 2020, 2024 has been Dosanjh’s banner year. He has sold out arenas and stadiums all over the world, including BC Place in Vancouver and The O2 Arena in London, during his highly successful Dilluminati tour that ends on Dec. 29 in Guwahati. Tickets for his multicity tour in India sold out in 30 seconds.

The tour was initially limited to North America but was later expanded to Europe, the United Arab Emirates and India, given the frenzy the singer generated with his live performances on social media, especially the one at the Ambanis’ pre-wedding bash in March. A video from the event, in which Bollywood stars groove to his music, has over 288 million views.

Later, the singer made history by becoming the first Indian artist to headline a music performance on “The Tonight Show,” with host Jimmy Fallon rightly introducing him as “the biggest Punjabi artist on the planet.”

Conventionally, Punjabi music has been popular in its home state, and among the Punjabi diaspora spread across countries such as the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Australia, as well as cities like Delhi, which is deeply influenced by Punjabi culture. But over the past few years, the genre has crossed borders and boundaries and seen a meteoric rise, its traditional folk sound becoming more contemporary, the Punjabi lyrics often blended with hip-hop beats.

Dosanjh has been significant in taking Punjabi music to new heights. In 2023, when he collaborated with Sia on a Punjabi-English song, Indians couldn’t believe Dosanjh had made the Australian singer-songwriter sing in Punjabi. In March, he made a surprise appearance at the Grammy-winning Ed Sheeran’s concert in Mumbai and made the British singer-songwriter sing in Punjabi for the first time, too. Soon afterward, he released a track, “Khutti,” with the American rapper Saweetie. He also did a Punjabi-Spanish crossover track, “Palpita,” with the Colombian singer Camilo.

Dosanjh is currently among the most sought-after singers in India. Since October, he has collaborated with multiple A-list stars, such as Alia Bhatt, Karthik Aaryan, Varun Dhawan and Prabhas to create promotional songs for their latest film releases. That the iconic actor Shah Rukh Khan collaborated with Dosanjh on his latest song is a testament to the Punjabi singer’s rising stardom.

Dosanjh also starred in one of the most critically acclaimed Hindi films of 2024, playing the role of Punjabi singer Amar Singh Chamkila, who was mysteriously assassinated in 1988, in a biopic. Called the “Elvis of Punjab,” Chamkila was the highest-selling artist in the region during the ’80s and was famous — and infamous — for his sexually explicit lyrics.

With over 23 million monthly listeners on Spotify and almost 25 million followers on Instagram, Dosanjh is not only the biggest Punjabi singer in the world, he is also among the most desirable men in India. “Diljit Dosanjh is officially India’s most fashionable man,” read a Vogue India headline recently. He enjoys a massive fan following — especially among women — and has become a role model for young Sardar boys, who often dress up like him at his concerts, wearing his signature Coachella outfit.

While it was only in 2024 that Dosanjh became a household name in India, throughout the course of two decades he has slowly and effectively changed the way people look at Sardars and present them in South Asian pop culture.

One of the mainstays of growing up in Delhi in the 1990s and 2000s was a steady stream of “Santa-Banta” jokes. The fictional duo were middle-aged Sardars, or turban-wearing Sikh men, and were often presented as naive, stupid and poorly versed in the English language.

If not Santa or Banta, the joke would involve an unnamed Sardarji, but the traits would remain the same. Jokes were also made at the expense of high-achieving Sikh men in Indian society. For instance, a popular one involved the veteran track and field athlete Milkha Singh at a beach in England. When a Briton asks him if he is relaxing, his response is, “No, I am Milkha Singh.” Others involved Giani Zail Singh, who became India’s first Sikh president in 1982.

These jokes created stereotypes about the Sikh community — that Sikhs relied more on brawn than brain in life, and that their supposed absence of common sense and social skills made them a laughingstock. Their perceived lack of English language skills also lowered their standing in the public imagination. (A colonial hangover has caused possession of English language skills to be seen as a marker of class in India.)

Scholars and folklorists who have studied the phenomenon say there has been cordiality between Sikhs and the majority Hindu population, who have recognized the generosity and courage of the Sikh community. “Yet, within these many positive constructions lie the half-submerged images of the Sikh as a butt of jokes, the Sikh as someone dangerous, the Sikh as a potential anti-national, the Sikh as the ‘other,’” writes the Mumbai-based academic Manpreet J. Singh in her book “The Sikh Next Door.”

These jokes reflect deep-rooted anxieties among the Hindu majority, who perhaps suffered from a hurt ego and harbored insecurities as the minority Sikhs became more prosperous and successful in different fields of life, explains Singh.

While Hindus harbor similar anxieties about other minorities, like Muslims and Christians, apprehensions about Sikhs have a unique history. In 1947, when Punjab was divided between India and Pakistan, displaced Sikhs from West Punjab arrived in areas such as Delhi and Kanpur. Their loud and aggressive nature, indifference to preexisting social customs and new businesses disrupted market norms and social life in these regions. “In [the] course of time, as Sikhs broke into the existing markets, constructed houses and flaunted their prosperity through lifestyles verging on flashiness, they added to the existing apprehensions and reservations,” writes Singh.

Comprising less than 2% of the population, there are over 20 million Sikhs in India, according to the 2011 census. The majority of them live in the Indian state of Punjab. Sikhs are a highly prosperous community, who have left a mark in diverse fields, including politics, business, science, sports and entertainment.

Over the last few years, a series of protests, police complaints, court petitions by Sikh groups and arrests over the circulation of jokes about Sikhs have reduced their presence in pop culture. In 2007, a bookseller in Mumbai was arrested for stocking the “Santa and Banta Joke Book,” a collection of Sardarji jokes. In 2013, a man in Jalandhar spent two weeks in jail for sending a series of “offensive” jokes to a Sikh man. There is now an awareness that these jokes are unseemly and inappropriate and people shouldn’t expect Sikhs to laugh at them, even in the spirit of humor.

In the popular imagination, Sikh men — with their beards and turbans — were considered unattractive and undesirable. In school, I remember being anxious about having a crush on a fellow Sardar classmate, fearing that my friends would make fun of me. Recently, I found some threads on Quora and Reddit where Sikh men have shared their struggles with dating. One of them said that even his sister didn’t find Sardars attractive and wanted to marry a Punjabi Hindu man instead.

In mainstream Hindi cinema — or Bollywood — with which my friends and I grew up, which drew so much from Punjabi culture, Sardar characters were usually included to offer comic relief. And they were played by non-Sikh actors. In a bid to create a caricature, adult Sikh characters were sometimes made to wear a “patka,” a square piece of cloth worn by Sikh boys to cover their topknot until they are old enough to wear a turban — a portrayal that many have found disrespectful.

The first time the lead hero of a Bollywood film was a Sardar was in the 2008 action comedy “Singh is Kinng,” starring the popular actor Akshay Kumar. However, Kumar, who is not Sikh, received flak for not tying the turban properly and wearing stubble instead of a beard. Moreover, his character of Happy Singh was a good-natured but goofy man, bearing similarities to Santa and Banta. (Perhaps the only saving grace of that film was a promotional song Kumar did with Snoop Dogg which celebrated Sikh pride.)

Since then, many popular actors in Bollywood have played Sikh men on screen despite not being Sikh in real life. It was only in 2016 that Dosanjh became the first turbaned Sikh to be cast in a mainstream Hindi film, albeit in a supporting role. In “Udta Punjab,” a film about the rampant drug abuse in Punjab, he played the role of a police officer and shared the screen with one of the country’s foremost actors, Kareena Kapoor Khan, which made people take notice of him.

Since then, Dosanjh has been cast in several Bollywood movies as the lead hero and has starred opposite numerous popular actors, including Anushka Sharma, Kriti Sanon and Kiara Advani. However, all his characters were happy-go-lucky men whose role — once again — was to provide comic relief to the audiences.

“A male Sikh in Indian cinema is loud and boisterous, his gregariousness a genial indicator of his underdeveloped social etiquette,” wrote Singh in “The Sikh Next Door.” “Even if he is shown as good-hearted, he is either a simpleton or a socially awkward character on the verge of being a caricature. In most cases, his colourful clothes, his strange mannerisms and even a differently structured physical body make him the subject of ‘carnivalesque curiosity.’”

Singh said these images did not just construct the Sikh in a “diminutive manner” but also placed him on the “periphery of a majority culture.” “Built within the images is a systematic negation of the validity of his cultural difference. His difference is portrayed not as one which needs to be recognised and accorded a place of its own but in terms of a joke or a spectacle.”

This perhaps changed earlier this year when Rhea Kapoor, one of the few women producers in Hindi cinema, cast Dosanjh as the eye candy in the film “Crew” — a heist comedy, which stars Sanon and fellow actors Tabu and Kapoor Khan as air hostesses smuggling gold from India to the UAE. It was refreshing to see a Sardar be sexy on-screen and flirt with Sanon. Perhaps Hindi cinema needed the female gaze to make the audiences realize there is more than one way to look at turban-wearing men and that they could be hot.

Dosanjh’s foray into cinema opened doors for other Sikh actors in Hindi cinema. The actors Ammy Virk and Manjot Singh have been cast in several popular films in the last few years. Dosanjh had earlier paved the way even in Punjabi cinema, where he was among the first turban-wearing actors to be cast in lead roles and has some of the highest-grossing films to his credit.

At his Mumbai concert earlier in April, a visibly emotional Dosanjh spoke about the misconceptions people have had about Sardar men in fashion and entertainment. He remarked that when people would say Sardar men cannot be fashionable, he would say in response, “I will show you how.”

And he has. Dosanjh is arguably the most fashionable male celebrity in India at the moment and he has effectively used fashion to change the image of Sikh men in pop culture. “Back in the day, everybody said the turban guy is not fashionable because that’s a different genre; the turban is very traditional. The turban and fashion [were not seen as] compatible. But for me, from day one, I knew I could do this,” he said in an interview with Esquire magazine.

He has not only shown how Sardar men could be fashionable, he has turned the turban into a style statement. I’ve heard from many friends how Dosanjh and Virk’s popularity has removed a shame that was once attached to Sikh identity in the minds of some people.

A self-confessed “sneakerhead,” Dosanjh’s footwear collection boasts iconic pairs from brands such as Balenciaga, Gucci and Off-White. Fashion journalists have observed how obscure indie brands will feature alongside luxury brands in his looks. “I like Bode, Loewe, Bottega Veneta,” he told Esquire. They now include Dosanjh as part of the “Bode Boy Club” in Hollywood, which consists of celebrities like Harry Styles, Ryan Reynolds and the Jonas Brothers, who are often spotted in the brand’s creations. His watch — an Audemars Piguet Royal Oak 15400OR, customized with diamond-studded dial, straps and bezel — is hard to miss at concerts.

But on stage, Dosanjh prefers the traditional look of kurta and chadra. “Because I came from [a] very small village. I want the world to know where I’m from,” he told Esquire. Dosanjh has borrowed his name from his village Dosanjh Kalan, which is 20 miles from Jalandhar city in the state of Punjab. He proudly shares how his musical journey started by singing and playing the tabla and harmonium in Gurudwaras. He released his first album in 2002 and was first noticed for a song in 2009.

The fact that Dosanjh is not fluent in English — a trait that earlier made Sardars the butt of jokes — has added further to his appeal. His videos from Coachella, where could be seen speaking in broken English and acknowledging that his English skills were weak, made people root for him. “Vibe te vibe match kari,” or “the vibes should match,” he said instead and the crowd roared in applause.

His appeal and persona also bear similarities to Shah Rukh Khan, arguably the biggest superstar and the benchmark for celebrity in India. Both had humble beginnings, their successes were organic and stardom came very naturally. In his interviews, Dosanjh is extremely humble but he doesn’t shrink from owning his achievements — a quality that is also seen in Khan. Both enjoy a massive female following and make it a point to acknowledge and make their fans seen.

However, anxieties around Dosanjh’s rising stardom and assertion of Punjabi Sikh identity can be noticed in India. He often uses his now-famous catchphrase “Punjabi aa gaye oye” (“The Punjabis have arrived”) and ends his shows with the song “Main Hun Punjab” (“I am Punjab”) from his recent film on Chamkila.

Sikhs are often looked at with suspicion and assumed to oppose Indian national identity, given the history of separatist insurgency in Punjab in the 1980s and ’90s. Statements made by Punjabi singers are closely watched, as many of them are based in Canada, which is a base for Khalistan supporters — those who want an independent Sikh nation in the Indian state of Punjab.

Dosanjh has shied away neither from expressing his love for India nor acknowledging the violence and brutalities that have taken place in Punjab. He is among the few celebrities to have called the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in Delhi a “genocide.” He has acted in films based on the riots and the insurgency and his next film, “Punjab ’95,” which is currently stuck with the censor board, chronicles the life and work of the human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra, who was known for uncovering over 25,000 illegal killings and cremations involving the Punjab police during the insurgency.

In interviews, Dosanjh has said that he highlights his Punjabi identity because Punjab is a “small state” in the large country that is India. Yet the wider region of Punjab is not just limited to India but shared by its neighbor Pakistan, and there is a thriving Punjabi diaspora spread all over the world, which doesn’t always associate with India. Hence, any assertion of Punjabi identity — especially on a global stage — tends to create anxiety among Indians.

But Dosanjh has always been known for challenging the status quo, and he is now on the path to becoming a globally recognized pop star, reaching a pinnacle of popularity never before achieved by a Sikh man.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.