“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers every Monday and Wednesday. Sign up here.

Tunisia’s president-turned-autocrat, Kais Saied, is at a critical juncture. His nation’s economy is on the verge of collapse and, without an injection of capital, the government risks defaulting within the year. But Saied, who rode into power in 2019 on the slogan “the people want” and who took sole control of the country almost two years ago amid a wave of popular support, after years of political gridlock and economic decline, has limited options for how to wrest Tunisia from the grips of economic disaster — and none of them is particularly what “the people want.”

Instead, the populist is left to choose from a narrowing field of options, all of which come with hard trade-offs he has failed to prepare his constituency for, leaning instead into the rhetoric that made his takeover in July 2021 wildly popular: that Tunisia’s problems were the result of a few corrupt individuals whom he would root out.

The reality is, of course, far more mundane but also more complex. After a decade in which most political will was focused on jumpstarting the country’s nascent democracy after the fall of Zine El Abedine Ben Ali, rather than crafting sustainable economic policy, a series of blows has left the North African nation’s finances in tatters. The COVID-19 pandemic, which ground tourism — one of the country’s major revenue drivers — to a halt; the war in Ukraine, which has wreaked economic havoc, given the higher price of Ukrainian wheat, a staple of the Tunisian diet; and the global cost-of-living crisis have done little to diminish the nation’s reliance on international loans to cover the costs of imports and increasing state expenditures.

In past financial crises, this is the point at which Tunisia has turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which made its first loan to the country in 1964. In the politically turbulent decade since the revolution, negotiations with the IMF have been a rare constant. As government expenditures rose and key sources of foreign currencies, such as tourism and phosphate production, experienced protracted crises, two loans from the fund have provided a direct injection of cash and often been a precondition for other lenders to get involved. And, indeed, negotiations for a new loan agreement have been ongoing for over a year. However, more recently, Saied has struck a different tone. Lambasting IMF “diktats,” he has implied that Tunisia might walk away from the arrangement entirely.

Successive IMF programs have been highly unpopular in Tunisia: They are associated with an era of protracted economic crisis, new debts and demands for tighter budgets. A new agreement would almost certainly require unpopular cuts in public spending and reductions in civil service wages, as well as subsidies on energy and potentially even bread, vegetable oil and couscous. With the prospect of a default on the horizon, Saied has taken actions that have triggered both concern from Tunisia’s international partners and feverish speculations: If not the IMF, where could he turn to instead?

Some speculation has focused on alternative foreign funders: If the IMF’s conditions are deemed unacceptable, perhaps China, which has in recent years invested heavily in Africa, would be willing to offer loans under better conditions. Similarly, some have suggested that Gulf countries or the BRICS bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) might step in as an alternative lender. However, there has been little indication that this is anything more than speculation. China’s appetite for African debt appears to have substantially decreased, and there have been no movements to connect Tunisia to the BRICS New Development Bank. Many potential foreign funders, including the United States and the European Union, seem to have made Tunisia signing on to an IMF loan a precondition for further loans. While many Western partners seem unfazed by Saied’s turn away from democracy, his inability to turn the economy around has proved to be more alienating.

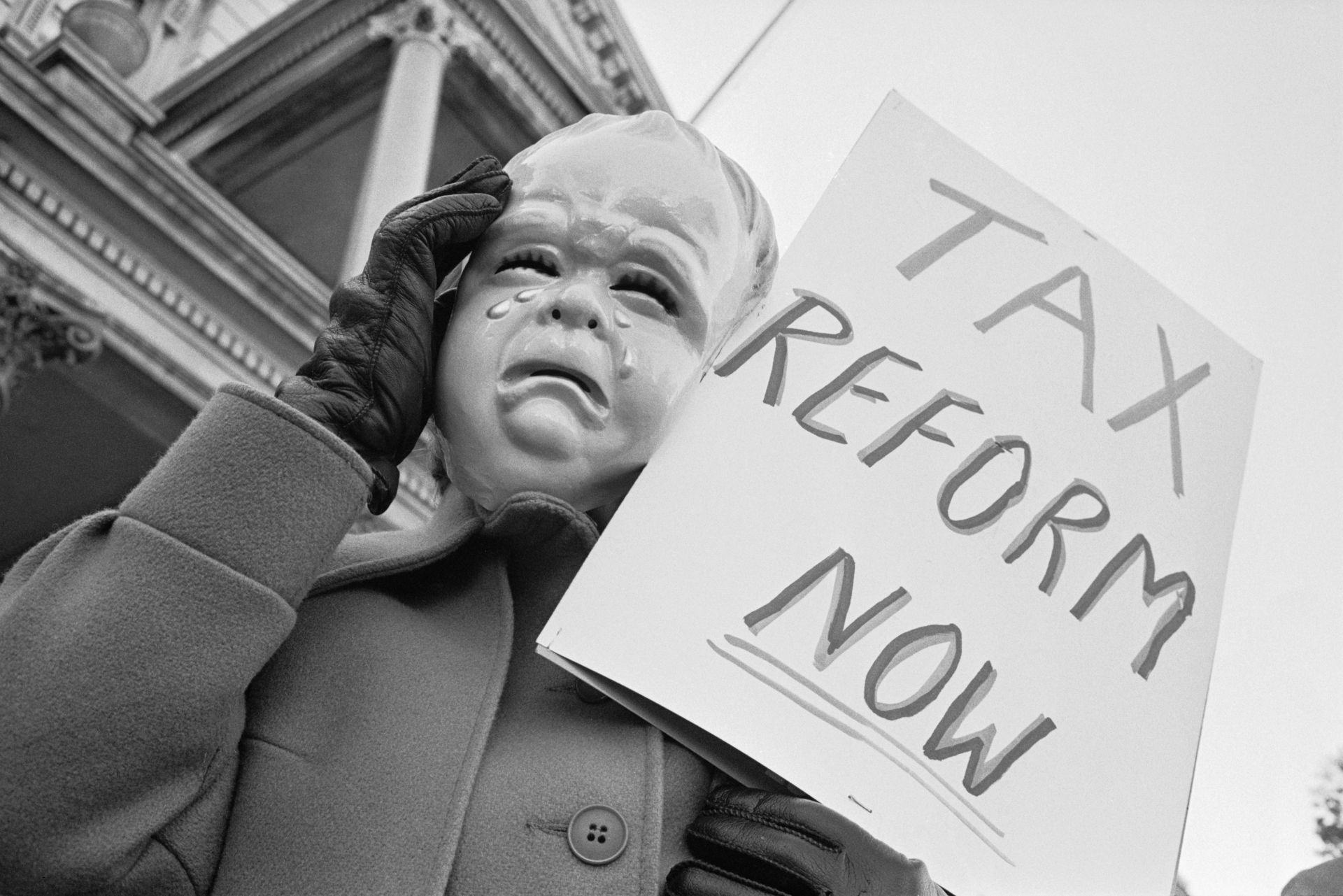

Tightening public expenditures — the crux of the IMF negotiations — is difficult for Saied politically, as much of the country’s infrastructure, from roads to landfills to hospitals, are in worsening condition. The Tunisian government is the largest employer in the country. As politicians tried to answer the revolution’s call for “work, freedom and national dignity,” thousands of state jobs were created. Trimming the public wage bill would put millions of Tunisians in financial straits. Cuts in subsidies are understandably unpopular, and restructuring state-owned enterprises is both practically challenging and an affront to large political constituencies. If he wants to avoid these conditions, this leaves the country with perhaps only one option for Tunisians to, as Saied declared recently, “count on themselves” and break not only with the IMF but with a decades-long pattern of relying ever more on foreign loans: tax reform. Boosting tax revenue could potentially shore up the government’s budget, making the need for a loan less urgent.

So can Tunisia tax itself out of this crisis?

In the short term, the answer to this is almost certainly “no.” There are two main reasons for this: timing and politics.

Increasing tax revenue takes time. Tunisia has actually increased its tax income in recent years: Its tax-to-GDP ratio, a common measurement that can give insight into how well a government is generating economic resources through taxation, has increased since 2011 and recently seen some of its sharpest improvements. But this is generally an area of slow and steady increases, rather than leaps forward. The average annual increase in Tunisia’s tax-to-GDP ratio both before and after the revolution has been around half a percent — a move in the right direction but not the kind of increase that can replace foreign loans in the short term.

In fact, Tunisia’s tax revenue is already relatively high compared with other countries in the region. It’s on par with Spain, relative to the size of its economy, and substantially higher than the average for other nations in the Middle East or Africa. Upward room is not endless. Many taxes are also tied to the overall performance of the economy — the country would collect less in income taxes, for example, if firms and individuals earned less. These kinds of taxes would almost certainly dip for some time if Tunisia defaulted on its debts. Attempts by other countries to quickly improve their tax income in an economic crisis — such as Ghana in recent years — have shown that the amount of tax revenue is not usually an area of dramatic shifts. Even if new taxes were introduced or rates increased, the time they would take to come into effect would leave Tunisia liable to its creditors.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to overcome is not that the tax rates are too low in Tunisia but that evasion is high. A study by the German research institute Friedrich Ebert Stiftung found that, in 2015, half of the lawyers in Tunisia’s tax registry did not report any taxable income.

Crucially, time is not all that is needed. Taxes are not merely an administrative tool; they are deeply political. Increasing efforts to collect taxes from different constituencies — be it business elites, importers or workers in Tunisia’s enormous informal sector — would encounter political resistance.

The government’s recent attempts at increasing domestic revenue offer a clear example of this. On one end of the spectrum, they included an increase in VAT rates for services provided by lawyers and other liberal professions and a new wealth tax on expensive properties. On the other end, they included a new lump-sum tax for informal workers. While the informal sector makes up the majority of the Tunisian labor force, it also includes many of its poorest workers. For those living without a regular income, lump-sum taxes, even if they are low, can be difficult to pay and even more difficult to justify in the middle of an economic crisis. Already, many associate the country’s tax system with a lack of fairness and transparency — those taxpayers most easily identifiable for further contributions may also be the same ones who already feel unfairly burdened. Depending on how they are introduced, tax increases may prove just as challenging for Saied’s political image as subsidy cuts. Consequently, there may be limits to the amount of tax increases that his government would actually be willing to go through with.

Implementing reforms requires coalitions that can sustainably support them. One of the origins of Tunisia’s post-revolutionary economic crisis has been a successive lack of economic vision by governing coalitions that have been built based on political alliances rather than shared economic programs. This crisis directly contributed to the deep unpopularity of post-revolutionary politics, to Saied’s electoral victory and public acquiescence to his authoritarianism. And yet it is a mistake Saied has made every effort to repeat. While he has been busy in recent years completely reshaping the country’s political system — drafting a new constitution and successively dismantling the country’s democratic structures — none of this has been directed at building a coalition to promote a new economic vision or improved administrative capacity. Instead, recent arrests of prominent opposition leaders have marked a further deepening of his authoritarianism.

This is one of the pointed tragedies of Tunisia’s current situation. In a moment when all economic options come with substantial trade-offs and will shape the country for decades to come, the Tunisian people have been stripped of the opportunities to weigh in on these decisions.

If Saied’s goal is to reduce Tunisia’s dependence on international finance, address domestic economic inequality and maintain an interventionist state, improved taxation will inevitably need to be a critical part of any reform in these directions. The importance of this is one of the few steps that virtually all observers of Tunisia’s current economic crisis can agree on. Because tax reforms will take time, they need urgent support. While they can be imposed as a condition of an IMF loan, critically, they do not present an immediate alternative to one. Even with a strong tax plan, if other external financing is not forthcoming or a new IMF arrangement is not agreed on, Tunisia faces a default — with all the costs that this implies for its population and Saied’s political future. In the short term, taxes are not an alternative to debt. But in the long term, they can be an avenue toward a more equitable and more independent Tunisia.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.