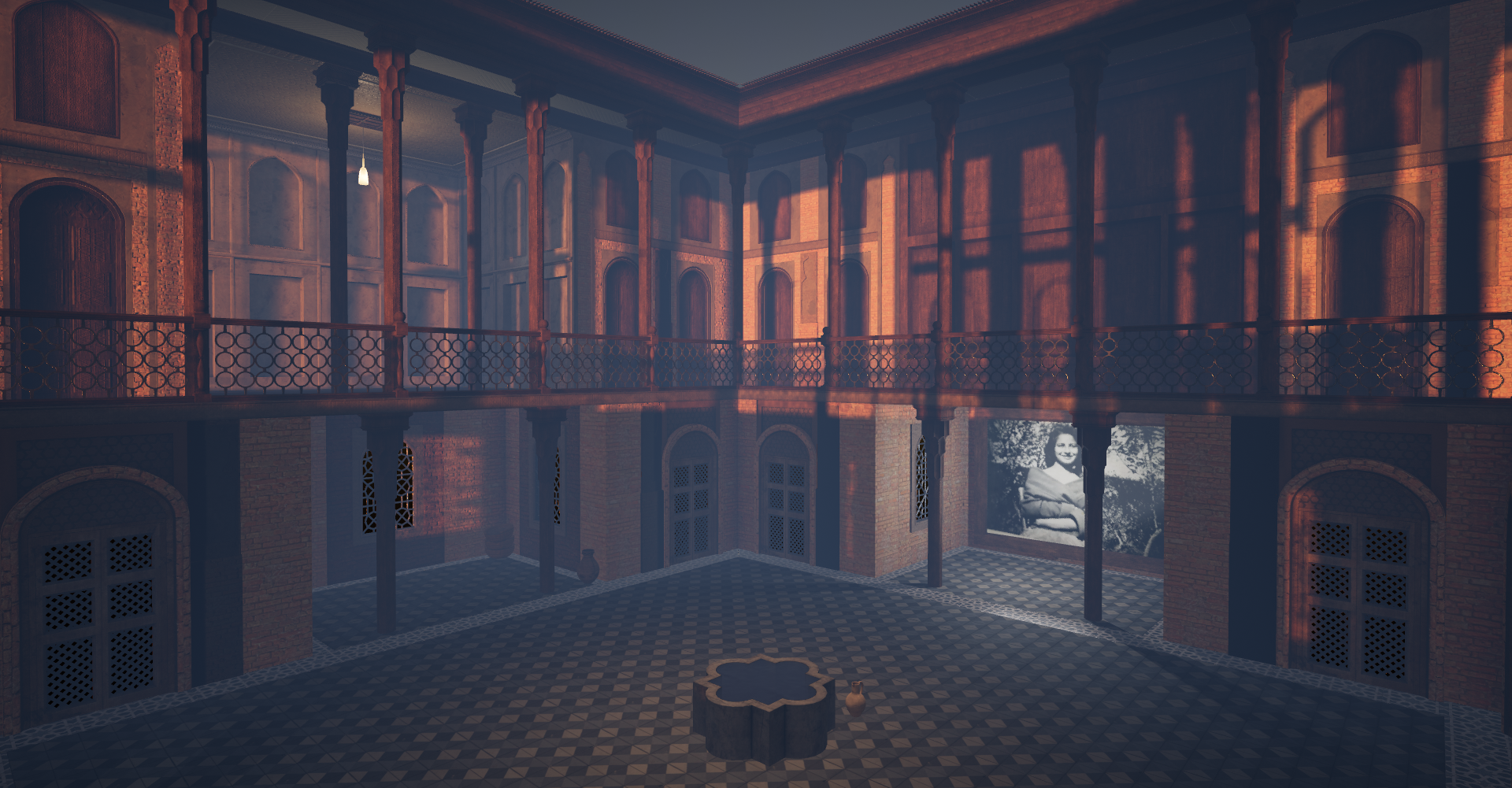

As you step into Basil Al-Rawi’s “House of Memory,” a vast, dimly lit internal courtyard awaits you, with ornate latticework windows — or “mashrabiya” — beckoning from each side. Wooden balconies frame the top level, while the floor beneath is made up of a distinctive geometric pattern. Sunlight filters through, creating an interplay of light and shadow that adds another dynamic element to the environment, which is modeled after a traditional Iraqi “shanasheel” (the word refers specifically in architectural terms to the mashrabiya, but is often a metonym for a particular style of Iraqi house). In one corner, a large black-and-white portrait photo of a young woman with a voluminous coif and a decollete neckline is displayed on the wall. As you approach, you suddenly find yourself plunging into darkness. The shanasheel around you has transformed and been replaced by the outline of trees and yellowed, sun-beaten grass below your feet. The voice of a woman breaks the silence.

“This is a photo that I really love,” she says in Arabic in an Iraqi dialect. “It was taken during my adolescence before I started to mature. I tried to imitate the actresses, and I loved fashion and dressing up.”

The subject of the photo, whose voice tells its story several decades later, goes on to explain that it was taken when she was no older than 16, in her family’s garden in the al-Adhamiya neighborhood in Baghdad. As she does so, leafy fruit trees and flowery bushes come into view around you and the sound of birds chirping fills the air. Sunlight starts to illuminate the scene. You notice a stone out of the corner of your eye. The woman continues her reminiscing, describing the breakfasts her family would enjoy in this serene setting. A picnic blanket suddenly appears, with plates full of food, along with a pitcher and a set of small glasses, just as she is describing them.

“I remember feeling really satisfied and proud of myself during this time. I was at peace.”

She continues, describing the small wooden desk and chair her father would sit at to write, which also materializes before your eyes. She shares a few more nostalgic memories before the whole scene dissipates and you find yourself back in the shanasheel, ready to be immersed in someone else’s walk down memory lane.

Al-Rawi, the creator of the “House of Memory,” is an Iraqi-Irish multidisciplinary artist based in Cork, Ireland. He says the objective behind the virtual reality experience is to preserve the personal stories and memories of Iraqis living in the diaspora by transporting viewers into intimate, immersive environments based on participants’ recollections of photographs from their past. I was able to experience the installation when I unexpectedly came across it at the Democracy x Change conference this past spring in Toronto, Canada.

“The house is not supposed to be location-specific, but is more of a psychological location, supposed to be evocative of an Iraqi architectural space which connects with the past,” Al-Rawi tells New Lines. Its design is based on architectural plans and photos of a number of different houses found in the book “Traditional Houses in Baghdad” by Ihsan Fethi and James Warren. Published in 1982, the book is an architectural study that explores the design, structure and cultural significance of traditional residential buildings in Baghdad, with insights into how they reflect the social, economic and environmental conditions at the time of their construction.

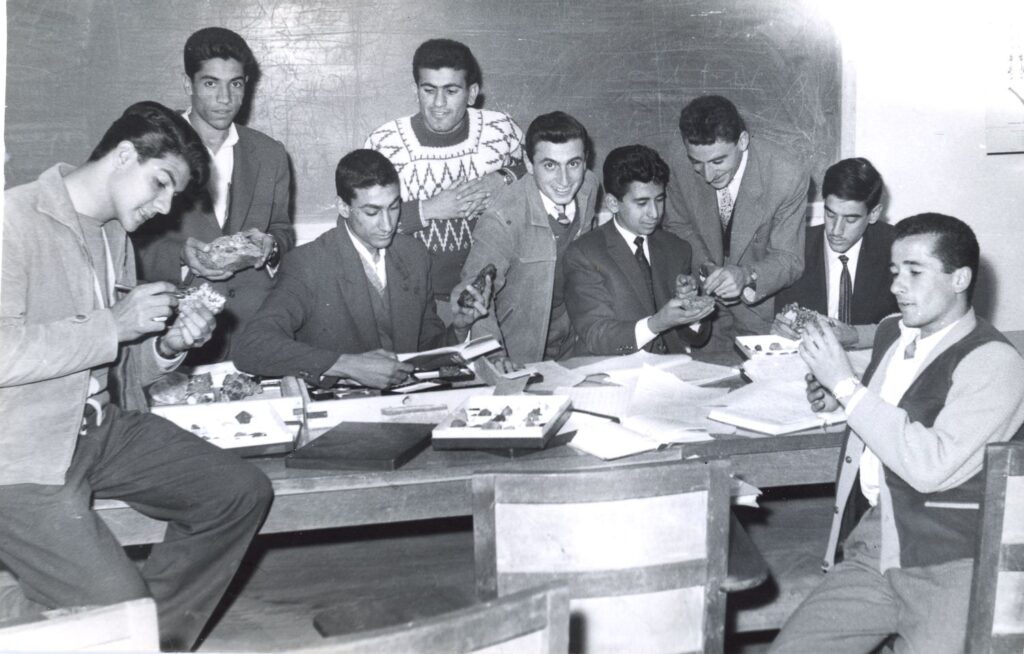

Al-Rawi’s own experiences growing up in Ireland with an Iraqi father inspired his latest creation and its predecessor, The Iraq Photo Archive. Poring over images from his father’s youth in his photo albums, he was struck by their stark contrast with media representations of Iraq, which often depict the country as nothing more than a site of conflict. Their effect was all the greater because the absence of social media and video calling made it even more difficult for Al-Rawi to connect with that side of his family and identity.

“Growing up in Ireland, my visual impression of Iraq was informed by mass media representations of conflict — the TV news, films and especially video games,” Al-Rawi says over Zoom. “As a young person of Arab heritage, this was very affecting, as these depictions were at odds with the narratives and images I then saw at home with my family.”

He started to ask his father about the photos, and was inspired by the memories that were shared over the years. “I started to realize the potential and power for these kinds of personal archives,” Al-Rawi says. “They can become a way to retrieve memory and communicate individual stories, which can then feed into more collective histories and create a counternarrative, or counterarchive.”

He notes that many of the formal archival collections of photographs from Iraq were held in Western institutions and cataloged from a colonial perspective in places like the Library of Congress and the Gertrude Bell Archive. These ethnographic-style images, taken primarily by Western travelers, diplomats and researchers, frequently reduce the complexities of Iraqi culture to simplistic stereotypes, framing subjects in Orientalist ways.

Ironically, the foundational principles of photography were influenced by Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, also known as Alhazen, who was born in Basra in 965. His pioneering work in optics and his invention of the camera obscura laid the groundwork for the development of photography, including his insights into light, vision and image projection, which were crucial to the creation of the first cameras.

Al-Rawi’s mission to create a counterarchive also took on a newfound significance following the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, as images of aerial bombardments and military targets once again dominated any representation of the country. Seeking to amplify the voices and perspectives of Iraqis themselves, Al-Rawi created the Iraq Photo Archive as an open platform for people to submit their own family photographs and share the stories behind them. Participants were then invited to take part in in-depth interviews designed to elicit memories specifically about the moments in the photos. Other open-access projects with similar motives have sprung up in the last decade. Perhaps the most well known is Middle East Archive, which describes itself as “a creative archive that retrieves lost memories from the Middle East and Maghreb” and has over 234,000 followers on Instagram.

But rather than simply displaying the photographs, Al-Rawi wanted to create an “expanded photographic moment.” He decided to use the recollections to reconstruct immersive virtual environments, allowing viewers to step into the participants’ memories. Al-Rawi’s background as a filmmaker and cinematographer informed his decision to use virtual reality as the medium for the project. He taught himself how to 3D-model, then enlisted the help of a programmer to help with the coding.

“It’s like a magic trick a little bit, isn’t it? You put on these goggles and you step into another world,” Al-Rawi says. “The VR medium allows you to be playful. It affords some storytelling capabilities that can affect you quite emotionally — the way we respond to light and sound, including voice, and the feeling of being present with the storyteller.”

Al-Rawi’s decision to use VR was also influenced by his observations of how Iraq has been represented in video games like Call of Duty (2003), Conflict: Desert Storm (2002) and Desert Strike (1992), which was released one year after the end of the Gulf War and became Electronic Arts’ bestselling video game that year. He noted a troubling trend of the country being depicted as a backdrop for conflict and violence, often in the context of first-person shooter games. Last year, Seattle-based Highwire Games released Six Days in Fallujah, a tactical first-person shooter video game set in the real-life Second Battle of Fallujah in 2004, after its original developer, Atomic Games, went bankrupt over controversy surrounding the game’s appropriateness. The real-life U.S. military also relies on virtual reality reconstruction, using photorealistic 3D replicas of places like Baghdad during operational training prior to deployments in conflict. In addition, virtual reality exposure therapy is used to treat veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan who experience post-traumatic stress disorder. Sometimes they even incorporate assets from commercial video games like Full Spectrum Warrior, which can have better quality graphics, into the therapy.

“Iraq is treated as a site of extraction, not only of its resources and its culture, but now of its trauma. It’s the extraction of its trauma to obtain profits through entertainment,” Al-Rawi says.

The project’s virtual environments are informed by the artist’s research into the architectural and cultural heritage of Iraq, which has also faced widespread destruction. Because of the nature of their construction, as well as the devastation resulting from the Gulf War, the 2003 invasion and decades of economic sanctions, many traditional domestic spaces like the traditional Baghdadi courtyard house depicted have been lost or lie in disrepair, adding an extra layer of meaning to the “House of Memory.”

“The thinking behind this was that the courtyard space of the house would be a conceptual space for encountering these photographs,” Al-Rawi says. “It gives a sense that the photographs are not out of place, that they’re in a historical place, and there’s another layer of conveying the idea that the encounters are going to be something from the past.”

One scene inside the “House of Memory” unfolds just 30 miles north of Baghdad, along the Tigris River, in the sparsely populated farming town of Tarmiyah, known for its citrus fruits. Because of its strategic location between two main roads running north from the capital as well as historical tensions between local Sunni communities and Shiite militias, it remains a hotspot for Islamic State group sleeper cells even after the group’s territorial defeat. But “strolling” through the “House of Memory” and coming across a sepia photo taken amid the lush palm trees in 1978, you would hardly guess that such a place could be so volatile. It shows two young men posing with a classic car, capturing a moment of camaraderie and leisure in a serene location. The man on the right is lounging casually on the car’s hood, his mustache prominent and thick, with mid-length hair typical of the 1970s. His voice proceeds to narrate the scene that has developed all around you as he describes the pleasant memories he associates with the picture.

“This was the best, lovely time of my life, about to finish my education. I was a member of the Communist Party and behind me is my comrade.” He says that they were members of an underground youth organization but that as young, hopeful men they were less concerned with regime change and more with fulfilling their dreams of living life the way that others outside of Iraq were permitted to live. He describes being forced to flee the country as things became increasingly dangerous under then-Vice President Saddam Hussein’s violent crackdown on communists and other political dissidents.

Before leaving the country, he said farewell to the comrade in the photo. “I showed him my passport and told him, ‘I am leaving. I cannot stay.’ … I haven’t seen this guy since 1979. I’ve tried to look for him, I tried to find out where he is. I went to Iraq after the invasion. They told me he died or was killed. I don’t know, but I wish I could see him again. He’s a lovely, nice guy.”

“House of Memory” was initially shared with participants and some members of the public during a residency at the Incubation Space at The LAB Gallery in Dublin and at the Arab British Centre courtesy of Shubbak Festival in London in summer 2022, as part of the evaluation process during the final stages of Al-Rawi’s doctoral program. He also shared the project at the Saw Centre in Ottawa, Canada, and then in Toronto the following week. There are plans to continue showing it at future festivals.

Al-Rawi tells New Lines that the project has had a profound effect on the participants, many of whom felt a deep sense of nostalgia and connection to their cultural heritage. One participant, for example, described feeling as if she was right back in her Baghdad garden after experiencing the VR work.

“She said she wished life in Iraq would go back to how it was when she was a kid, for her grandchildren to enjoy the same life,” Al-Rawi recounts. “There’s this idea of wanting to go back to the past, but we can’t. The experience affords you this opportunity to step into the past for a brief moment and encounter a moment from there, viewed through the lens of now and the storyteller’s personal recollection.”

He stresses the importance of preserving the regular stories of a people who have faced war and dislocation, particularly the elders who leave us day by day.

“You know, there’s a personal element to this as well, too. My father was going to be the first subject to be interviewed in this process. But he passed away about six weeks after I started it. So it’s tinged with this kind of idea that I can’t ask those questions anymore,” Al-Rawi says “It’s just really important for us to take the opportunity to record those things and to ask questions.”

As Al-Rawi looks to the future, he is focused on expanding both the Iraq Photo Archive project and “House of Memory” by building partnerships and securing funding to make the VR experience and public archive more widely accessible. By preserving these personal narratives and creating immersive spaces for cultural connection, the project aims to continue challenging the dominant, often dehumanizing representations of Iraq and the Middle East, and to celebrate the rich diversity of individual stories. The Iraq Photo Archive continues to welcome new submissions.

“There’s a real power in the construction of these counterarchives,” Al-Rawi says. “When you foreground the individual’s narrative and perspective, you start to create connections on a very human level, and those stereotypes and misrepresentations can start to crumble.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.