Warning: This essay contains spoilers for Pablo Larrain’s film “El Conde.”

Type the phrase “Pinochet T-shirt” into Amazon.com’s search function and you’ll find a few choice offerings. The first is a T-shirt that can be customized to any color and that reads “Mi General Pinochet’s Helicopter Tours, Established 1973,” the year Gen. Augusto Pinochet came to power in the military coup in Chile. This shirt is emblazoned with an image of a blue sky and a red helicopter with a body falling out of it.

Other options include a shirt that says “Pinochet Was Right,” which also features the image of a helicopter, while another sports the saluting image of Pinochet, decked out in his crispest military attire. A little more internet sleuthing and you’ll find shirts worn by the Proud Boys and other militias that say “Pinochet Did Nothing Wrong” on the front and “Make Communists Afraid of Rotary Aircraft Again … Physical Removal Since 1973” on the back. These are also illustrated with bodies falling out of helicopters.

On some of these shirts, you’ll find the letters RWDS, which stand for “Right Wing Death Squads.” In fact, the Nazi-tattooed mass shooter at a Dallas mall in May 2023 wore an “RWDS” patch. According to The New York Times and other news organizations, the acronym originated with the death squads the Pinochet regime used to kill political prisoners. The helicopters with bodies falling out of them, of course, refer to one of the dictatorship’s favored ways of disposing of activists and arrestees.

As is widely known, Pinochet, with the support of the United States, overthrew the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende in 1973. During Pinochet’s 17-year rule, the government brutally repressed those Chileans who supported democracy and human rights — thousands were killed, tortured, disappeared, imprisoned or exiled. Under the shock of Pinochet’s Draconian tactics, a series of extreme free-market reforms designed by Milton Friedman and economists trained at the University of Chicago were implemented, which included the privatization of public schools and social security, the destruction of labor unions and economic deregulation, leading to consolidation of wealth in the hands of the upper class and poverty and destitution for most.

Why has Pinochet’s use of helicopters to dispose of political opponents become a symbol of the far right in the United States? I’m not sure the Proud Boys and their affiliates have given a clear answer to this question, but it doesn’t take a lot of interpretive guile to figure out what’s going on here. On one level, the message is about their disparagement of democracy and the ways in which the right finds it perfectly acceptable to use extreme violence in order to amplify its fantasies of fascism and dictatorship. At the same time, it’s a throwback to the Cold War, when killing tens of thousands of people was deemed a reasonable strategy to protect U.S. and Western business interests. It represents the fascist vision of a state that is not afraid to do the most horrible things to its citizens in the name of what they call “Western chauvinism.”

I was thinking about the U.S. right’s glorification of Pinochet as I watched “El Conde,” a new movie by the Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larrain, now streaming on Netflix. El Conde (“The Count”) is none other than Pinochet, only here he is a 250-year-old vampire who cut his teeth (pun intended) during the French Revolution. Given the American far right’s revivification of Pinochet amid its celebration of fascism and insurrection, Larrain’s thesis seems all the more fitting: that in Chile, and indeed across the world, Pinochet never died; he can’t die, because Chile (like his supporters in other countries) refuses to kill him.

Filmed entirely in black and white, “El Conde” opens with a spooky shot of a haunted house in a barren desert landscape and with the voice of a distinguished English woman, who says:

Naturally, our dear count has tasted human blood from every corner of the world. English blood is his favorite, of course. He says it has something of the Roman empire. … Regrettably, however, the count has also sampled the blood of South America, the blood of the workers. He doesn’t recommend it. It’s acrid, with a doggy nose. A plebeian bouquet that clings for weeks to his lips and palate.

Then we see the face of Pinochet the vampire, who, to be sure, doesn’t really look like the actual Pinochet, for the film is not trying to depict Pinochet as much as it is trying to reimagine him. Dressed in a bathrobe, he is unkempt, tired and pockmarked. He’s sick of being alive. He wants to die. But his wife, Lucia, and her lover, the family’s Russian vampire-butler Fyodor, keep feeding him blood to keep him alive. They don’t want him to die, a sentiment shared by Pinochet’s avaricious and inept five adult children, who want to keep their old man alive until they have a firm grip on where he’s stashed away the millions of dollars he’s stolen from the nation’s coffers.

Soon enough, we learn that not only does Pinochet the vampire revere England and the Roman Empire, he’s got a thing for the French monarchy as well. Born in a Parisian orphanage, “The young Claude Pinoche … became a proud officer in the army of Louis XVI.” Then one day, while on a drunken rampage, he “discovered his true identity” when he bit a young woman on the neck. When confronted with his toothiness the next morning, Claude Pinoche quotes what the real Pinochet told a Chilean judge in 2005 when asked about his role as director of the DINA, Chile’s murderous secret police: “I don’t recall any of this,” says the budding vampire. “It’s not true. And even if it were, I have no memory of it.”

Played with a straight face, this 21st-century obfuscation in the mouth of an 18th-century vampire is pretty funny. And herein lies the movie’s scandal. What does it mean to laugh alongside the dictator who murdered and tortured tens of thousands of people and whose policies and legacies still have an unshakable hold on the nation? And what does it mean to feel that the repulsive figure of Pinoche the vampire is actually much more likable than the repulsive figure of Pinochet the real-life dictator? That’s not saying much. Nevertheless, the film works hard to highlight the vampire Pinochet’s emotional and all-too-human vulnerabilities: He wants to be loved, and he falls asleep every night holding hands with his wife.

In Chile, there has been little public reckoning with the legacy of the dictatorship’s human rights abuses. To wit, on Sept. 11 of this year, Chile commemorated the 50th anniversary of Pinochet’s coup and the death of Allende, the president deposed in the process. While the left used this moment to denounce the violence of the dictatorship, right-wing politicians, who hold the majority in the Senate, made a series of pronouncements criticizing Allende and justifying what they continue to see as Pinochet’s necessary intervention. These conservatives went so far as to read into the record and formally vote to approve a congressional statement from Aug. 22, 1973, just days before the coup, that condemned Allende for “a serious breach of the constitutional and legal order” and that asked the military to “immediately put an end” to these supposed violations. Furthermore, on Sept. 28, CNN Chile reported that the right-wing coalition writing the current draft of the new constitution voted to officially scrap preexisting language establishing “that the armed forces must respect the constitutional democratic order and human rights.”

Returning to “El Conde,” we can see then that Pinochet and his murderous legacies are alive and well in Chilean public life. The dictator remains ever present in contemporary discourse; his undead authority keeps the country from progressing both politically (e.g., the inability to approve a new constitution) and psychologically (e.g., the inability to have honest public dialogues about state murder and human rights abuses). The vampire Pinochet of “El Conde,” however, is not filled with the confidence and bluster of the real Pinochet. He is upset that he has been demonized by the public for being a thief. He has not, though, been demonized for his murder and torture of thousands of Chileans, nor for his implementation of failed neoliberal policies that have created massive inequality.

“El Conde” does not skimp on the gore. The young Claude Pinoche bludgeons and crushes skulls in quite graphic detail. When we move to the contemporary moment, the film takes much pleasure in the repeated consumption of smoothies blended up from human hearts. Back in 18th-century France, Marie Antoinette’s head is guillotined, an emotionally pivotal moment for the young Pinoche. He licks blood off the blade before proceeding to steal the head of the young queen from her grave as he “resolves to use his powers to fight against all revolutions.” For the next two centuries, he fights against revolutionaries in Haiti, Russia and Algeria. Finally, sick of being a mere soldier, he moves to a “country without a king … an insignificant corner of South America,” where he definitively reappears “in this land of fatherless peasants, Chile,” as Gen. Augusto Pinochet.

This sense of internationalism, while understated, is perhaps one of the film’s most fascinating aspects. Some novelists, like the late Roberto Bolano in “Distant Star,” have written about militant Latin American leftists who, channeling the legacy of Che Guevara, travel throughout the hemisphere to participate in as many revolutionary struggles as possible. On the other end of the political spectrum, members of the U.S. military were also traveling throughout the Americas to support counterrevolutionary dictatorships. In “El Conde,” the revolutionary impulse, be it anti-capitalist, anti-colonial or anti-monarchical, is confronted by a right-wing internationalist solidarity.

And while the film ornamentally celebrates the vampire’s coming of age as a defender of the French monarchy, where this internationalism is most present is in the relationship between Pinochet and (spoiler alert) the film’s alleged narrator, the distinguished Margaret Thatcher, former prime minister of the United Kingdom. As the film comes to its wild conclusion, we learn that Thatcher is also a vampire and, indeed, that she is Pinochet’s mother. On one level, this comical embellishment reflects the Chilean upper class’s cultural fascination with English high society; on another, what is being satirized here is nothing other than the origins of neoliberalism.

“Economics are the method,” the real Thatcher famously declared in 1981. “The object is to change the soul.” For both Thatcher and Pinochet, changing the soul meant sucking the collectivist impulse out of citizens through, among other things, the dissolution of public services and the elimination of organized labor. For Pinochet, this alteration of the soul was efficiently accomplished through torture, murder and disappearance. As Thatcher the narrator tells us, Chile had to be rescued from its “Bolshevik infestation.”

And if a little government corruption happens along the way — if the president and his friends and family get rich off all the money they are stealing from a state now flush with the cash not being spent on unimportant things like healthcare and education — then those are the spoils of war. Some of the film’s most humorous moments come from vampire Pinochet’s five adult children, who “screwed all the women and all the men, crashed all the cars and squandered all the state’s money on cheap wine and imitation velvet. They won wars and founded the country anew. And then they were left powerless, stripped of their honor.” They mope and whine and look under couch cushions for bank statements, lamenting that they will never gain access to their inheritance.

But they’re not going down without a fight. Or at least without a forensic investigation of the general’s hidden finances, and for this purpose they hire an accountant, a cute math-wizard detective nun bearing a striking resemblance to Renee Jeanne Falconetti in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 film “The Passion of Joan of Arc.” In addition to her gift for calculating “unspeakable sums,” the nun also happens to be the church’s best exorcist. The church, to be sure, is less interested in getting rid of Pinochet the vampire than it is in appropriating his stolen money, and it’s not afraid to get its hands dirty in order to find it.

Unloved by the public, and tired from his 250 years of anti-revolutionary blood sucking, the vampire Pinochet wants to die, but the cute nun and a surfeit of human heart smoothies revive him. She introduces herself in French, “the language of my Sun King,” or, as Pinochet notes, “the language of treason, and the war is never forgotten.” She promises to help find all the misplaced money, though what she really does is flirt with the vampire Pinochet and stir his atrophying heart.

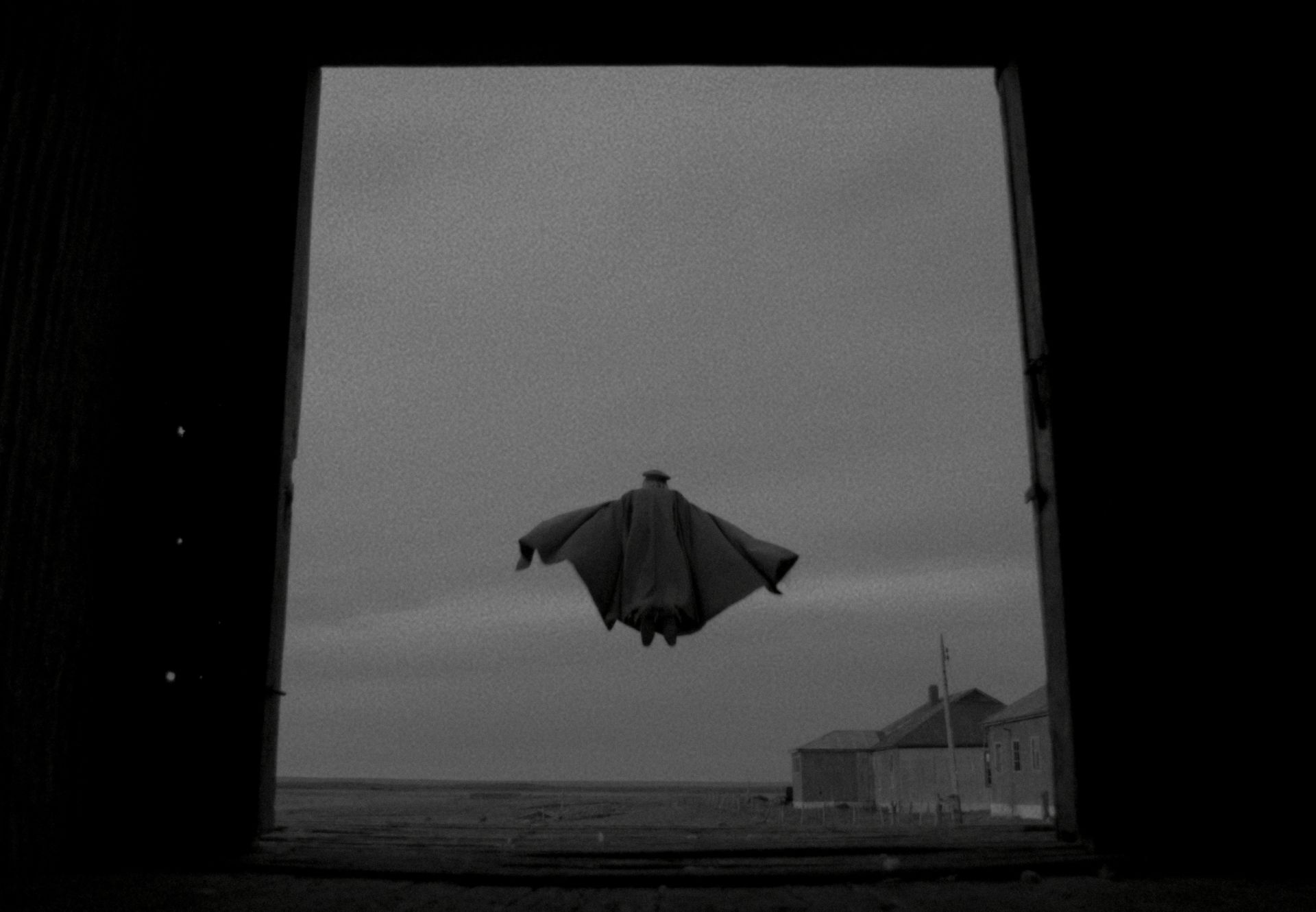

High jinks ensue. Throughout his life, vampire Pinochet refused to grant his wife and children eternal existence by biting their necks, but in an act of seduction the nun gets her own neck bloodied and, in the film’s most operatic scene, she soars in a state of ecstasy after being granted the ability to fly. She twirls and dances in the sky with childish delight as an amorous Pinochet looks on in approval. While at times we are not sure if the nun’s true loyalties lie with God or her own seductive powers, what we do find out in the end is that neither of these forces are strong enough to withstand the international vampiric power of Thatcher and Pinochet, the royal monsters of neoliberalism.

Larrain’s previous films, “No” (2012) and the brilliant “Tony Manero” (2008), are also rooted in the Chilean dictatorship. “No” stars the heartthrob Gabriel Garcia Bernal in the role of a Mexican advertising executive who comes to Chile in the run-up to the 1988 Yes/No plebiscite, a vote to decide whether Pinochet should remain in power. The film dramatizes the advertising campaign that Bernal develops to support the “No” cause, which would ultimately be successful by a narrow margin and remove Pinochet from power.

The film has been criticized by Chilean leftists for its simplistic portrayal of the grassroots organizing that led to the removal of Pinochet and for giving the misleading impression that all the credit for this dramatic political change should go to a television campaign penned by a foreign advertising agent. This critique is valid; nevertheless, “No” movingly highlights transitional justice and the complexities of creating major change in an atmosphere of terror and repression.

“Tony Manero” is, to my mind, Larrain’s best film. Set in the late 1970s, in the heart of the dictatorship, the movie centers on a character who impersonates John Travolta from “Saturday Night Fever” and finds himself mixed up in the murderous pomp of the dictatorship. It’s a political horror show enveloped in a disco period piece where the eccentric freedoms of U.S. kitsch culture are intertwined with a beastly nightmare of torture and authoritarianism.

In all these films, Larrain inventively reimagines Chile’s dictatorship while also animating its most horrific tactics (tactics that continue to be celebrated by fascists in Chile and in the U.S.). In other words, Larrain is doing what great artists do: creating fictional words that say more about reality than reality. If Chile’s political and social institutions have failed to provide the public with a way of honestly confronting the unspeakable violence it lived through, then this work must fall to artists. Chilean novelists like Pedro Lemebel, Diamela Eltit and Roberto Bolano, as well as poets like Raul Zurita and Elvira Hernandez, have lyrically articulated the contours and contradictions of a country that has demolished itself through political and economic violence. Along the way, they have created some of the most important Spanish-language writing and art of the past century.

Like these artists, Larrain is doing the important historical work of responding to the gross absurdity not just of the dictatorship, but of those in Chile who refuse to stop honoring the dictatorship. That Pinochet continues to live on, both in the hearts of Chilean elites as well as in the rhetoric, memes and T-shirts of fascists in the U.S., shows that it’s all the more necessary to laugh at, illustrate and try to understand the monstrous past and present that continue to feed him our blood.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.