Cunda is the biggest of the 22 islands governed by Ayvalık, a north Aegean district in Turkey. It shares a layered history with its mainland, starting with its name. Governmental websites and Google Maps adamantly refer to it as “Alibey” after a Turkish lieutenant colonel. Yet few people in Turkey call the island anything other than the more melodious “Cunda,” sparing it somewhat from the early republic’s nationwide effort to Turkify place names. Meanwhile the former inhabitants, the Eastern Orthodox Christians of the Ottoman Empire, used to call it “Moschonisi,” or the perfumed island.

Originally referring to the subjects of the Eastern Roman Empire, the word “Romios-Rum” came to denote Eastern Orthodox Christians as the empire’s territories gradually came under Ottoman rule. Non-Muslim communities of the Abrahamic religions were governed by the millet system that allowed them autonomy in religious and legal affairs, the Greek-speaking “Rum millet” being one of them.

Especially in the pre-nation-state era, “Rumness” could not be fully disassociated from Greek identity, given the language and cultural sensibilities of the people. In modern Turkey, the word “Rum” unequivocally denotes the Greek-speaking, Christian minority in the country. Beset by punishing taxation, pogroms, and state-led expulsion in the 20th century, the community is barely surviving today, with their schools shutting down due to a lack of students and their once-thriving businesses collapsing. The Rums are regularly among the top targets of hate speech in Turkish media, branded wholesale as the enemy whenever political tensions flare up in the Mediterranean. They are ostracized in their native country even though their presence in Anatolia dates back centuries before Turks set foot there in 1071, and the Seljuk Turks who captured large parts of the area after the 1071 Battle of Manzikert called their state the Rum Seljuk Sultanate.

On the island of Cunda, numerous hotels and house rentals use the word “Rum,” sometimes paired with “stone,” to describe their buildings, as Turkish vacationers easily associate these words with aesthetics and a charming touch of history. Completely bare of the people who built and used to live in them, their foreignness remains harmless, usable, and pleasant. Indeed, the low-rise houses made of dusty pink sarımsak taşı, a local volcanic stone, with corbeled wrought iron balconies and almond green, rose, and blue shutters, adorned with flushes of bougainvillea, regularly lure visitors. Some of these houses are private dwellings, some are boutique hotels.

The primary historical monument and the main postcard material of the island is the former Church of the Taxiarchs, restored and serving today as a museum chock-full of vintage objects including model ships, miniature tea sets, and alarm clocks collected and put on display by one of the richest families in Turkey.

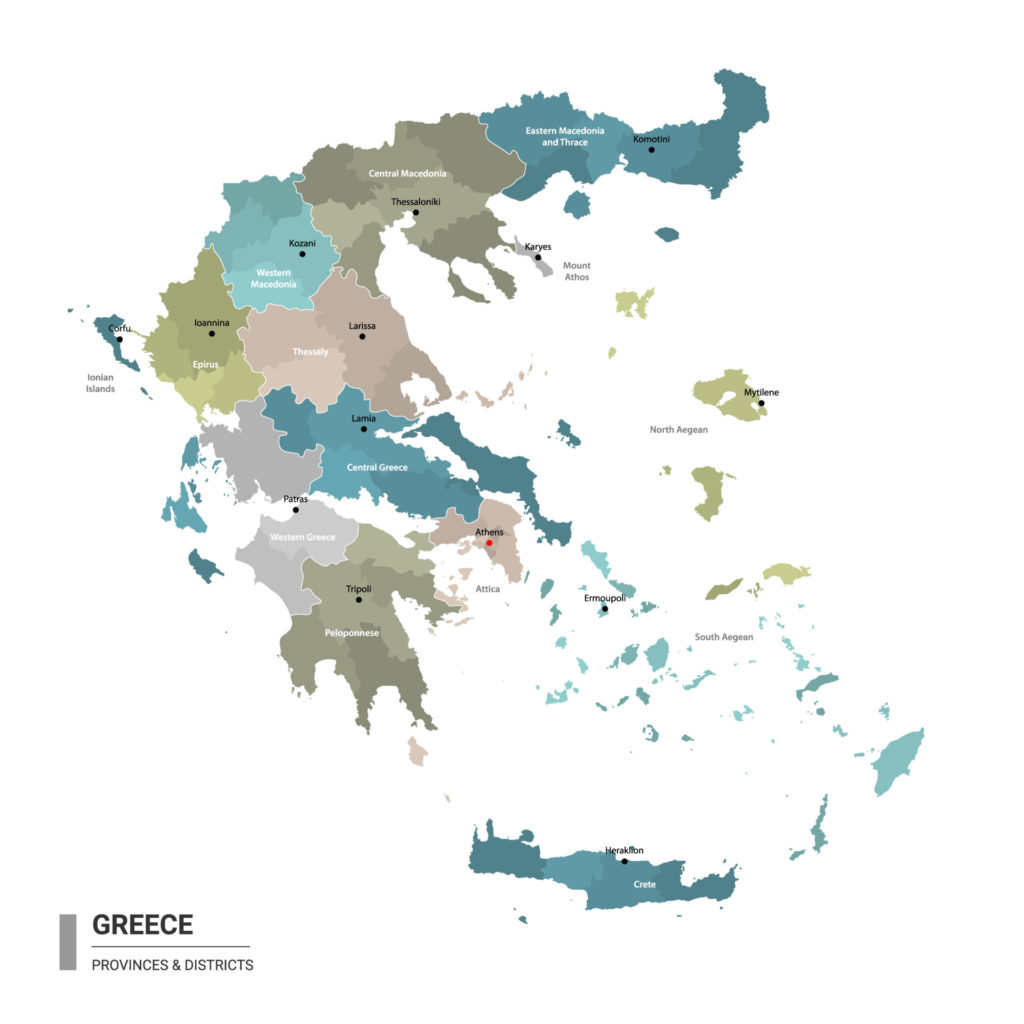

Before Rahmi M. Koç Museums renovated the church in 2014, it was in a state of disrepair with hollowed arch windows and deep fractures on its apse. The standing churches on the island have been stripped of their original function today, with another one restored and converted into a library by the same family, while the third and oldest was left to its fate as a ruined shell. According to accounts by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, the nearly 6,000 Rum inhabitants fled in the early 20th century. Those who created the island’s touristic appeal today were replaced by Muslims who came from Crete and Mytilene. Cunda’s current locals are their descendants.

For most of us in Turkey, having grown up with a thick curtain of nation-building myths that categorically ignore or downplay the destruction and bloodshed perpetrated by our compatriots in the first half of the 20th century, a closer look at Cunda and Ayvalık’s past entails a journey of unlearning.

Many people raised within the national education system in Turkey would attribute the current ethnic landscape of Cunda and the neighboring Ayvalık, as well as the silent traces of their antecedent, to the population exchange that took place between Greece and Turkey in 1923.

Though still a matter of dispute amid rivalry over natural resources, the borders between the two countries were delimited by the Treaty of Lausanne and, with the massive expulsion of people from their ancestral homelands, created the largely homogenized ethnic makeups of Greece and Turkey today. As one of the epilogues to the long age of empires and “a civilized version of ethnic cleansing,” in historian Çağlar Keyder’s terms, the exchange displaced some 400,000 Muslims living in Greece and nearly 1.2 million Rums in Turkey.

What on paper seemed to bureaucrats an ingenious arrangement to help both countries cement their own nationalist myths was in practice anything but. According to Bruce Clark’s “Twice A Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey,” newcomers to Greece from Anatolia were taunted as Tourkosporoi (seeds of Turks), while the equivalent insult for Cretan Muslims was yarı gavur (half infidel). Until the ends of their lives, thousands of families pined for the lands they were forced to leave.

Today, visitors to Cunda can buy locally produced olive oil, try the sublime lor cheese made on the same day in a dairy farm on the island, indulge in a bowl of syrupy fried lokma on the pier, and feast on some of the best Cretan specialties like the warm saganaki cheese, stuffed zucchini flowers, and prawns cooked with thyme. Taş Kahve, a high-ceilinged coffee house on the pier with tall windows colored on the arches, is spacious enough to accommodate both middle-aged local men and tourists eager to tick boxes on their Cunda checklist. What lacks in official historiography in Turkey is that this building, formerly Kafeneion O Ermis (Hermes Café), was vandalized and lay derelict long before the Treaty of Lausanne was signed.

Millions of Turkish adults today remember the cold, eerie sentence from history classes at school, describing our victory on the Aegean coast in the War of Independence: Yunanlıları denize döktük (literally, “We poured Greeks into the sea”). I do not recall a feeling of pity, shock, or sympathy but a sense of vindication. Invading soldiers should not have stepped onto our soil in the first place. Along with local Rum accomplices, the Greek army had killed our innocent compatriots, civilian Turks, so they deserved to be pushed off the land.

Such graphic statements carve a deep, if not indelible, place in the minds of children. What is taken in with easy disinterest at an impressionable age hardens into entrenched belief unless challenged with personal effort later on. To this day, around Sept. 9, which marks the independence of İzmir in 1922, newspapers perpetuate the very wording in that statement, exalting Kemal Atatürk’s army for how they “poured” the enemy into the sea.

In Cunda, September 1922 was a fateful month for many Rums. Clark mentions in his book that several hundred civilians of all ages were taken away and killed, and only some of the children were spared and sent to orphanages. In a recent correspondence about the island’s pre-exchange days, the author wrote: “The local bishop, Ambrosios, is said to have been buried alive on September 14, 1922. According to another local tradition [sic], several hundred islanders were killed on September 19th.”

I first went to Cunda in summer 2020. Upon returning from my trip, I had an aftertaste of a splendid, restful vacation, just as I had been promised by friends who had visited the island before me. As for the history of the island, I remained curious, but largely ignorant, until I came across Clark’s “Twice A Stranger.” In our correspondence, Clark said that Cunda was a prosperous and dynamic community of several thousand people, entirely Greek by language, religion, and consciousness. The main occupations, he added, were boatbuilding (for which the island was quite famous), fishing, and diving for sponges.

They paid the price for being on the wrong side of the Aegean at the wrong time, when the Ottoman Empire, with a final clutch at survival, was sacrificing its own people.

Early in the 20th century, life in Cunda as well as in mainland Ayvalık was upended with plunder, demolition, and killing. The Patriarchate’s records refer to acts of pillage and robbery in Ayvalık going back to the outbreak of the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), after which the locals were pushed to leave amid growing persecution. When they abandoned Cunda, churches were turned into warehouses and stables, the lamps and holy images in them were broken, paintings destroyed, and houses rendered uninhabitable. In 1915, according to Clark, the islanders who had managed to stay were forced to pay a large tax for the accommodation and clothing of the Ottoman armed forces. They paid the price for being on the wrong side of the Aegean at the wrong time, when the Ottoman Empire, with a final clutch at survival, was sacrificing its own people.

“Aivali: A Story of Greeks and Turks in 1922,” a graphic novel by Greek caricaturist Soloúp, tells the stories of Turks and Greeks who suffered from the population exchange. With potent illustrations of real-life scenes and distressing mental visions, it includes stories by four writers, enriched with a vast number of testimonies Soloúp drew inspiration from. Beyond acts of barbarity on both sides, the book discredits the vilification of the “other” in Turkish and Greek demarcations of identity with accounts of friendship, romance, and chance encounters sparking compassion.

Soloúp’s grandparents were born in İzmir. His grandmother Maria was among the many who were trapped in the great fire of İzmir in September 1922, a little after the Turkish army entered the city and declared its independence. Maria, hopelessly fleeing from rape, threw herself into the sea to commit suicide. She swam among dead bodies before being saved by an American ship. Like thousands of Rums who were trying to survive the fire, Maria wasn’t an invader. She was more Anatolian than millions of us in Turkey today can claim to be.

A memorable panel in “Aivali” hints at the maelstrom of faith, disbelief, and hope that Cunda’s inhabitants must have felt in 1922: A priest yells at fellow islanders on boats fleeing to nearby Mytilene from invading Turks. He tells them that Cunda is their fatherland, that they will live there in peace with the Turks again. Later in the book, a Turkish man with roots in Crete talks about what his ancestors discovered upon arriving in Cunda. Most houses had traces of massacres with stains of dried blood and corpses in wells. What they saw was more a sign of sudden, desperate exodus than a programmed expulsion. In the book “Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey,” edited by Renée Hirschon, the scene is thus described: “When we first came to Moschonisi, we were surprised to find that on the tables were dishes of food, some of it already on forks ready to be eaten.”

Elias Venezis, a prominent Greek writer in the 20th century whose story is included in “Aivali,” was one of the nearly 3,000 Rum men in Ayvalık aged between 18 and 45 who were forcibly taken to Ottoman labor battalions where they faced enslavement, torture, and death. According to historian Speros Vryonis Jr., “By and large, those thousands of Greeks in the slave labor camps had no official identity as such. They could (be made to) disappear quietly and without any fanfare.” Venezis, who was 18 at the time of his forced conscription, was one of only 23 survivors.

Ninety-eight years ago, the engineers of the population exchange wanted to forge two nations out of the agony of 1.6 million souls. The stories they left behind were erased either by political will or by the practical necessities of those who had to make home out of alien houses. Amid a landscape of rising Hellenophobia that’s not penalized in Turkey today, along with the government’s ethnocentric discourse and policies, the population exchange casts an enduring shadow on the collective consciousness of many Turkish citizens.

A trip to Cunda these days can begin and end with only scraps of knowledge diluted with omissions. “Just like Ayvalık, Cunda is unthinkable without the sea. … The stories of people and buildings begin with and end in the sea,” says a brochure by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism dedicated to the town, referring to a former orphanage along the island’s shore. The stories of its many inhabitants ended in those waters indeed, as they ran for their lives and never turned back.