We are supporters of Ali bin Abi Talib; we are not afraid. The damned Sultan Selim was slaughtering the Alawites. We landed in mountains to be eaten by monsters, but we ate the monsters. My brother Ali was a believer and a sheikh. He was like Sheikh Saleh al-Ali. I can’t tell you on the phone many secrets. I just want to see you in person so I can tell you about many things that are secret.

– Fawaz Khizam about his brother Ali Khizam

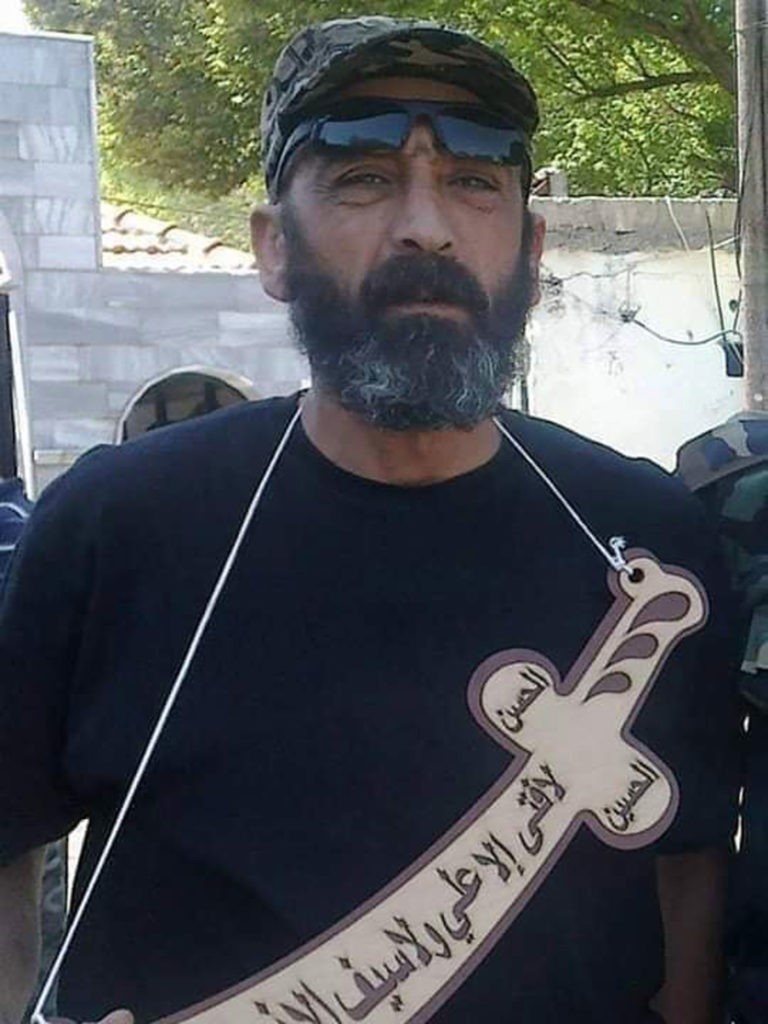

Social media is rife with fan pages, hagiographic elegies and even poetry glorifying Ali Khizam (1966-2012), a colonel in the Syrian army and an Alawite sheikh. Propaganda and reports from the Syrian regime support this picture of a hero. But after extensive interviews with his older brother, Fawaz Nazeer Khizam, and other fighters and sheikhs, along with testimonies from his victims, a very different picture emerges. This image of Khizam is one of a ruthless perpetrator who used his connections to the Assad family and his charismatic public image to provide sectarian and religious justifications of the regime’s murderous repression.

Public and political discussions about “sectarian violence” in Syria are often limited to Salafi Sunni jihadists. But there are many other dimensions to the sectarianism of this brutal conflict, not least the specter of such Alawite religious involvement in the violence. Sheikhs such as Khizam who double as military commanders or Mukhabarat (secret police) officers are a fundamentally overlooked feature of the Syrian conflict. These initially low-profile but high-impact perpetrators were fighters in combat operations, from soldiers on the battlefields of Syria to war criminals who committed atrocities against civilians.

The Alawite religion crystallized in the 11th century as a syncretic development of Islamic and pre-Islamic beliefs and practices, in particular paganism, Christianity and Shiite Islam. During the centuries of Ottoman rule, Alawites experienced ups and downs, including periods of confrontation with the nominally Sunni government, but also cooperation, and generally uneasy coexistence — like many other local communities. In his definitive study “A History of the ʻAlawis,” Stefan Winter debunks the myth of perennial victimization of the supposedly ceaselessly persecuted sect. The French mandate period, 1923-1945, brought opportunities for societal integration as Alawites began to enjoy education and emancipation; the French empowered certain Alawite tribal leaders and even established an Alawite state, which endured from 1920 to 1936. After Syrian independence, the instability and political competition affected the Alawite community, as their chances dwindled and many sought advancement by working in the public service, including military careers — as seen in the rise of former President Hafez al-Assad.

Under his three-decade regime, two rather paradoxical developments took hold in Syria. First, although many prominent positions in government were taken up by Alawites who flourished politically and financially, most Alawites did not benefit. Second, the secular Arab nationalism of the Baath Party offered a protective shield against political Islam but at the same time weakened the Alawite religion as new generations did not imbibe it as before. The period of President Bashar al-Assad’s rule then ushered further changes to inter-sectarian relations in Syria, but it was the conflict that set off fundamental shifts in the way that Alawites perceived themselves, and how others perceived them.

Sectarian relations during the rule of the Assad family are a deeply controversial issue. The paucity of research on the issue is part of the broader difficulty of conducting social research in Syria, but it is also due to the specifically taboo nature of the topic. Syrian school curricula did not even cover the various religions in an effort to create new generations of Syrians that were post-sectarian, reminiscent of Tito’s Yugoslavia. Opinions about the nature of sectarian relations and the prevalence of prejudice and racism vary widely among Syrians of all backgrounds. Some will argue that Syria is a fundamentally sectarian society and that the conflict was an inevitable, indeed natural outcome; others will deny any form of native sectarianism and blame the Iranians and Saudis for sectarianizing an otherwise peaceful Syria.

A more realistic assessment of Syrian sectarianism takes into account local and private settings in which inter-sectarian banter is common, including about and by Alawites. Jokes told by Alawite sheikhs about Ismailis and Sunnis, for example, are widespread, like this one that is told in Antakya: An Alawite sheikh goes to the city and encounters a Sunni sheikh, who, upon realizing his counterpart is Alawite, wants to kill him. “Why?” asks the Alawite sheikh. The Sunni sheikh responds: “Because any Muslim who kills an infidel will go to heaven.” “Wrong,” retorts the Alawite sheikh sharply, “If you really want to go to heaven, you should be killed by an infidel. So if I kill you, you will go to heaven.” Prejudice alone may not lead directly to violence, but it surely forms the cultural background knowledge on which violence is built.

The creeping capture of key power positions by certain Alawite henchmen close to the Assad family rapidly politicized sectarian identities and relations. Fanar Haddad summarized this nicely when he wrote that “domestic power relations … were sect-coded to a significant extent given the role of Alawi solidarity in a personalized, under-institutionalized system based on patronage and informal procedures.” One thing is certain: The conflict heightened sectarian tensions, profoundly polarized communities and deeply affected the collective sentiments of the Alawites. Sectarianization was both a consequence and cause in the conflict. The regime followed a strategy of sectarianization by arming Alawite militias and directing them to massacre Sunni settlements, which sparked an armed Islamist response equally sectarian and unforgiving.

In a wide-ranging study of Alawite identity based on in-depth interviews with religious leaders, Leon Goldsmith writes that the sheikhs’ political preferences “seem to be based on three key principles: security, equality and diversity.” Concretely this meant security of the Alawite community, equality between the sects and diversity of the society. These fragile principles came under severe pressure at the start of the uprising, when the Alawite community was put in an impossible position: stand with the regime or face dire consequences. The sheikhs also felt under pressure, but there was no single position among them: Whereas very few (if any) sheikhs joined the emerging opposition movements, most others seem to have turned inward and taken recourse to quietism, and again some others threw their weight fully behind the regime. While the quietism of Alawite sheikhs is well known, the category of pro-regime sheikhs is less so.

Some in this last category supported the regime by encouraging young men to enlist in the militias. Sheikh Muwaffaq Ghazal would often be seen in military camouflage, with his long white beard, armed with an AK-47, publicly and unabashedly advocating for Alawite youth to take up arms. He often stood side by side with notorious paramilitary leaders such as Mihraç Ural aka Ali Kayyali, lending an air of religious legitimacy to pro-regime mobilization. (His brother Badraddin Ghazal was a well-known sheikh in Latakia and was executed in 2013 by Jabhat al-Nusra.) Sheikh Shabaan Mansour too appears on the side of army officers and militia leaders, providing religious justification for their crimes.

Another example is Mohammad Barakat, who had long functioned as the director of the Homs Military Hospital and was at once doctor, sheikh and army general. In 2011, he approached Alawite youth and proposed they set up a “group” with the head of Air Force Intelligence at the time, Jamil al-Hassan. However, there is no evidence of these sheikhs having personally participated in the fighting, and they seem to have functioned only as figureheads, brokers or “chaplains” offering spiritual guidance and care — though this does not make them less implicated. Finally, within the category of sheikhs bearing arms, those who perpetrated violence are part of an even smaller subset, and even less is known about them. Khizam occupies a special place in this particular pantheon.

In April 2016, a significant number of Alawite sheikhs wrote and distributed a pamphlet titled “Declaration of an Identity Reform” to several major European news agencies. In this well-intended manuscript, they distanced themselves and the Alawite sect from the Assad regime and outlined a political transition for Syria’s future that was inclusive and democratic. However, the declaration abstained from detailed commentary on the ongoing war or direct critique of the regime but rather offered an abstract treatise of the moral and societal place of the Alawites in Syria. In fact, it contains no discussion of what led to the conflict, no admonishments against sectarian violence and not even an acknowledgment of the sectarian carnage that Syria suffered in the preceding five years.

Hassan Mneimneh has even argued that it is “a denial of the sectarian nature of the Syrian killing fields” that nowhere “addresses the depth of complicity to which the regime has driven Alawite Syrians … in flagrant opposition to the lived experience of the past multiple years.” After all of the killing, including by warrior-sheikhs, this treatise was seen as offering too little, too late. The declaration implied that the sheikhs, regardless of their religious authority or autonomy, were unable to stand up against the political and military might of the regime. They too were at once hostages and accomplices of a regime that only militarized a community, sectarianized a society and brutalized a war in which Alawites were not winners, but losers.

Khizam was born in 1966 in Qardaha, the Assad family’s ancestral village in rural Latakia, to a religious middle-class Alawite family. Khizam’s father, Nazeer Khizam, was an officer in one of the regime’s four main intelligence agencies, the State Security (Amn al-Dawla). His mother was a daughter of the Shalish family, which is related to the Assad family. Ali himself was close to Hafez’s eldest son, Bassel (1962-1994), until the untimely death of the heir-apparent in a car crash, after which Khizam’s friendship and patronage shifted to Maher al-Assad, the younger brother of Bassel and Bashar. Maher began pursuing a career in the army and became commander of a brigade in the Republican Guard, ultimately taking de facto charge of the Syrian Arab Army’s (SAA) elite Fourth Armored Division.

Khizam was thus well-placed in the regime and on his way to becoming the right-hand man of the future Syrian president. But Hafez believed that Maher was too hot-tempered for effective leadership and therefore did not possess the character to succeed him. Instead, the shy and ungainly Bashar was groomed to succeed the president, but Khizam’s patronage and intimacy with the family remained unassailable. In one photo taken some time between 1994 and 1999, he stands right next to Bashar, in full uniform, dapper and provocative.

To his friends, Khizam was known by his nom de guerre, Abu Haidara (“Father of Haidara”), after his son. Posthumously, he would be known as “Commander of the Martyrs,” and his fans established a Facebook page dedicated to him: “Lovers of the Commander of the Martyrs Ali Khizam Abu Haidara.”

Khizam was not from a family that traditionally begot sheikhs and so had to become a sheikh through induction, in a private ceremony, to demonstrate his knowledge of the Alawite faith in front of other sheikhs. More or less around the same time, in the mid-1980s, in a fairly unusual dual-track training (religious and military), he enrolled in the military academy, specialized in infantry, and came first in a national marksmanship contest. Khizam then enlisted in the Republican Guard as lieutenant and worked his way up to colonel in the Special Operations unit. This unit underwent a brutal physical training process and required absolute loyalty to the Assad regime, as well as ruthlessness in dealing with its detractors and enemies. According to his brother, Khizam accompanied Hafez on many of his trips as part of his security detail.

By the time the uprising broke out in 2011, his dual careers and identities as sheikh and officer had merged into a single identity, a blend of the martial and religious. Voluntary exit was not an option, either as sheikh or as military officer, as his fate was closely tied up with that of the regime: Khizam existed in a social universe in which the perpetuation of the regime and protection of the Alawite community was key. The two identities were mutually reinforcing in some ways. For example, the Alawite religion contains certain theological elements that are secret and not to be disclosed to outsiders. The authoritarianism of the Assad regime also required secrecy: of its structures, policies and staffing. From this perspective, being a low-profile Alawite sheikh facilitated being an officer in a highly secretive military institution. Throughout the 1990s, Khizam climbed through the ranks, and when the uprising began, he inevitably came to play a formidable role in its repression.

There is little to no evidence that Khizam was versed in Baathist ideology or much involved in the party. His sectarian hatred on the other hand, is well documented, manifesting itself not only in his public and private discourse, but also in acts seen by both his colleagues and his victims. According to his brother, Khizam would talk about the ninth Ottoman Sultan, Selim I (1470-1520), who was known for his massacres of Alawites and Shiites during his military campaign against the Persian Safavid Empire in the 1510s. Selim I has come to occupy the image of a bogeyman in the collective memory of Alawites in both Syria and Turkey. The specter of supposed Alawite victimization loomed large in Khizam’s historical imagination, and his animosity against Sunnis was explicit.

In one video, probably from 2012, he is seen at a wedding dressed in a white suit, heavily intoxicated and surrounded by a group of young admirers. He sends his wife away, sings some songs, calls the opposition fighters “dogs” and then talks to his fans about being wounded in the battlefield, losing comrades, finally exhorting the boys:

“Guys, pray for the Lord of the Worlds to save this country for good, so Mr. President will be fine, and the sect will be fine. And I swear by the Commander of the Faithful, you have been fighting the same jihad for 1,400 years, and you are still fighting with Ali bin Abi Talib.”

This clip is highly relevant because nothing in what Khizam says in this private setting reflects the regime’s official stance on the conflict. He does not refer to Syrian nationalism, Baathism or even the regime’s alleged campaign of counterterrorism. Instead, there is only sectarian incitement, as he invokes Ali ibn Abi Talib (the Prophet Muhammad’s nephew and son-in-law), who holds divine relevance for Alawites.

Khizam was not only a sheikh but also something of a bard. The Syrian coast is famous for its nonmetric strophes for songs, called ‘ataaba. These traditional melodic forms of lyrical poetry are improvised and sung by men as a lamentation or expression of outrage or reproach. Khizam was a prolific ‘ataaba singer but in rather unusual fashion included sectarian motifs in them. In one video, he is seen sitting with the guards drinking and socializing in a room. He begins singing a famous ‘ataaba but alters its lyrics into a sectarian message:

They don’t have conscience, and no religion,

Don’t deal with them, and don’t lend them money,

A group of blinds, not men, with no religion,

They have no chivalry until doomsday

Here, Khizam clearly refers to Sunnis, or at least Sunni fighters. His ‘ataaba not only are motivational songs to inspire men and woo recruits but also serve as wartime propaganda to demonize the enemy. In all of the videos in which he is seen to be singing, younger fighters listen to him with awe and clap and cheer loudly at the lyrics. In another video, he is seen leading his men in a dabke (a Syrian folkloric circle dance) that is particular to the Latakia region. The video clearly shows the men bonding over the folklore of their regional, sectarian identity as they dance in the soon-to-be invaded neighborhood of Darayya, with a bulldozer parked ominously behind them.

Throughout 2011 and 2012, Khizam became increasingly famous for his apparently warm friendship with Issam Jada’an Zahreddin (1961-2017), a major general in the Republican Guard. Zahreddin, with his dashing personality, flamboyant moustache and muscular build, hailed from a famous Druze military family: His great-grandfather was Gen. Abdulkarim Zahreddin (1917-2009), minister of defense in the 1960s. Technically, Zahreddin was Khizam’s commanding officer, but in reality, they seemed to be more like comrades-in-arms. The dynamic duo exemplified the minoritarian security structures that the Assad regime is built on. A Druze and an Alawite were portrayed as fighting a Sunni Islamist insurrection to keep up appearances of an inclusive regime, but behind the façade, there was an unmistakable sectarian dimension. There are countless photos and videos of the two men, fighting on the battlefields side by side, or relaxing in backstage environments, joking and laughing.

In one video, the Republican Guards are cooking an evening meal in a kitchen. The atmosphere is informal, and the men are joking and enjoying themselves. Wearing a black tracksuit, Khizam is standing in a corner, tearing up from the onions he is chopping, prompting the cameraman to tease him: “Look at hero of Baba Amr, Ali Khizam, as he is chopping the onions.” The troops burst into laughter as Zahreddin walks in and playfully mimics the chopping. The clip looks like a scene from a frat house party, but it was filmed amid the brutal cleansing campaign the Guards were conducting in Homs.

In another video, this time from Deir ez-Zor, Zahreddin and Khizam are lying on the ground in a tent of a pro-regime Bedouin tribe, relaxing, as their subordinate officer Mirabo al-Aqel (1988-2012) is singing an ‘ataaba about Bashar. These videos of the “bromance” between Khizam and Zahreddin humanize the two men by portraying them as having gone through hardships of the battlefield but also showing the audience that they are able to relax from those hardships in an informal environment.

Khizam formed a group of around 50 men who would make up his core group of loyalists throughout his rampage across Syria. Almost all of them were Alawites, and the very few non-Alawite defectors from this group that I managed to locate refused to be approached, let alone interviewed. However they did confirm that all of Khizam’s men received a ring that symbolized their personal loyalty to him. His older brother Fawaz and one of his former subordinates were willing to speak about him and his life, and they provided contextual information and valuable details but strictly avoided taboos such as violence against civilians or overtly sectarian motives.

The common theme expressed by all these people who had known Khizam was that he was admired and revered by everyone. At least on record, many of his soldiers remembered him as a fearless fighter who would face the machine guns head-on. In pro-regime media, he was known for his “courage” or “audacity,” but in reality, among the millions of video clips of battles from the Syrian conflict, there is no footage of Khizam fighting in an actual battle. The one exception is a video clip in which he is seen shooting an automatic rifle at the rebels in Homs, but it looks staged.

His “courage” then could be read as ruthlessness, as Khizam’s record of war crimes is long and varied: He tortured, executed and massacred people; directed fighter jets to bomb civilian neighborhoods; and on several occasions used civilians as human shields while advancing on the front lines during urban fighting. Khizam was involved in repression of demonstrations in at least three theaters: first, the Damascus suburbs of Eastern Ghouta in 2011, then the beleaguered Homs neighborhood of Baba Amr in 2012 and finally in the eastern city of Deir ez-Zor. All of his campaigns ended in large-scale massacres of opposition civilians.

Starting in March 2011, Syria became politically polarized as some neighborhoods began massive protests against the regime, others saw significant paramilitary mobilization to repress them, and yet others remained fairly uninvolved and sat on the fence for a host of reasons. That summer, as the regime escalated and militarized its repression against the uprising, Syrian army officers and soldiers began defecting and hiding in their hometowns or opposition neighborhoods. The initial response was to defend the demonstrations, but the defense escalated into skirmishes, and by the end of 2011, a low-intensity civil war was in the making, parallel to the ongoing mass demonstrations.

On July 29, 2011, defecting army officers announced the formation of the Free Syrian Army, and the uprising-repression dynamic morphed into an asymmetrical armed conflict. The regime’s response was a brutal mix of mass arrests, death threats and the deliberate segregation of cities through a system of checkpoints. Khizam and his unit were profoundly influential in this period. According to some sources, he even underwent a training course with the Revolutionary Guards in Iran for several months and returned to Syria in 2012, but this period is shrouded in mystery.

Damascus is a prime example of this repressive strategy. The people in the city’s older, central neighborhoods remained aloof, whereas those in the larger, poorer suburbs in Western and Eastern Ghouta demonstrated in large numbers. The Republican Guards were deployed to repress the demonstrations beginning in the summer of 2011. It is likely that in this period, Khizam mobilized men, built his team and maneuvered himself into a paramount position. He was then sent to the northeastern neighborhoods of Misraba and Douma, where he carried out cleansing operations by swarming the streets and shooting at demonstrators. In the extant videos, hundreds of Guards are seen walking through the main streets of Ghouta, yelling intimidating slogans and bursting their AK-47s in the air in a deafening salvo.

Anyone who decided to shoot back was overpowered and liquidated. One video skips to a point after the violence where the Guards are seen in a building with the spoils of war, going through (and possibly looting) the supplies of an opposition apartment in Douma. They show off placards with anti-regime slogans, mobile phones, internet routers, digital cameras, laptops and a banner that says: “Expect the fall of the Syrian regime in Ramadan exclusively by the hand of the Syrian people. The Friday of Your Silence Kills Us — Douma, 29 July 2011.”

The Guards seem to have shot this video to suggest that the local opposition activists were well organized, insinuating foreign support. Finally, to my knowledge, there exists only one video clip in which both Khizam and Zahreddin are seen with dead bodies. This highly relevant, leaked, 2-minute clip shows the Guards in the aftermath of a massacre in the Misraba neighborhood in the spring of 2012, triumphantly standing around the mangled corpses of men lying in the mud. Ecstatic, they yell famous pro-regime slogans, kick the bodies and with their boots step on the victims’ faces. Zahreddin is seen pontificating, with his index finger up, as he robs the corpses and distributes the money and valuables he finds in the pockets of the dead men. The camera then shifts to Khizam, who is standing around with his weapon, taciturn and pensive, almost solemn. When the cameraman addresses him, he points at the bodies and says: “Dogs.”

The veil on Khizam’s ruthlessness is fully lifted in one video from the Eastern Ghouta neighborhood of Saqba. A slim young man in civilian clothes is seen standing on the ledge of a roof. He seems to have escaped there by himself during the ongoing massacre and stands terrified of certain execution. Zahreddin is seen looking up, arguing with him to get down as a group of Guards film the scene in amusement. Zahreddin first tries to assure the man that he should not be afraid but should come down and simply sign a pledge not to demonstrate. But as the petrified teenager refuses to come down, Zahreddin loses his temper and orders him to “come the fuck down right away.” Khizam is then seen walking into the frame, calling Zahreddin: “Boss! Now everyone who sees him in the neighborhood will eat the same shit like him. Let me throw him down from up there!” Here, Khizam’s demeanor is brusque, impatient and ferocious, showing a rare glimpse of his battlefield behavior. Locals from Saqba, now living in Germany, confirmed that the boy was later captured and executed.

Beginning in March 2011, daily or weekly mass demonstrations took place in Homs’ mostly Sunni and working-class neighborhoods of Baba Amr, Jobar, Khaldiya, al-Wa’er, Bayada, Deir Baalbeh, and to a certain extent the mixed Sunni and Christian, middle-class areas such as Insha’at, Bab Sba’a, Karm al-Zeitoun and Bab Dreib. The regime closed off the squares and cut off communications, and demonstrations retreated into neighborhoods like Baba Amr, where a motley collection of poorly armed FSA factions attempted to withhold the regime’s onslaught. By October 2011, the regime sealed off Baba Amr, and skirmishes between FSA and SAA became regular occurrences. The regime then began blockading and besieging the insurgent neighborhood more seriously in an attempt to choke them into submission and surrender.

The storming of Baba Amr on Feb. 28, 2012, was exceptionally brutal. The army surrounded and shelled the neighborhood, after which the Guards launched a ground invasion on the bombed-out area and, together with State Security personnel and Shabbiha militias, executed hundreds of people. The FSA had retreated and those who stayed behind were civilians who were either unable or unwilling to leave. Videos of the immediate aftermath of the massacre show civilians executed against walls and on sidewalks with large exit wounds in their heads while the Guards walk around, insult the victims and film the corpses.

Khizam was not simply present in Baba Amr; he acquired his nom de guerre as a result of his involvement in the campaign: Lion of Baba Amr. I have not found any surviving eyewitnesses to confirm his presence there, but his brutality is documented in other ways. For example, one middle-class couple now living in Europe had their house stormed by Khizam, “a big and arrogant man with a beard,” they recalled. “He was like a monster, we were terrified by his look.”

Baba Amr was a major event for the course of the conflict and for Khizam’s career. It catapulted him to national fame, fundamentally changing his standing and bolstering his reputation, so much so that according to his brother, Khizam had a direct line to Bashar, who would call him on the phone and talk about the most recent developments, thereby bypassing the formal chain of military communication. Khizam allegedly invited Assad to come and see for himself how safe Baba Amr had become. On March 27, 2012, only three weeks after the massacre, Assad visited Baba Amr in a staged visit in which he promised the return to normality and met with a few selected Syrians who chanted slogans and pledged their loyalty to him.

After the campaign, a leaked video shows Republican Guard Gen. Badia al-Ali giving a speech to dozens of Guards, who are standing in a mosque in Baba Amr. In the lengthy video, the general extols his troops as “the strongest men who confronted the militants, killed them and chased them.” Remarkably, he placed the storming of Baba Amr in an international context, arguing that “the whole world was betting on Baba Amr” and that “the international political situation changed after the fall of Baba Amr,” which, according to al-Ali, had been compared to Stalingrad. He then concluded with a whopping statement: “The Republican Guard means that we fight on all the territory of the Syrian Arab Republic, to edify the words of the Honorable Leader Bashar al-Assad. Mr. President, he is the one who gives us strength through his wisdom, patience, and successful management of the crisis, and the whole world is surprised by the wisdom, steadfastness, and patience of this president.”

Regularly interrupted by the usual pro-Assad slogans, the general promises rewards and celebrates the destruction of Baba Amr. Zahreddin is visible and even interjects; Khizam is also present, though he is standing inconspicuously on the side.

Khizam was promoted and moved on to the next killing fields. After the fall of Baba Amr, he fought in the battle of Daraya in 2012 to take back the town. This theater of war included the battle for the shrine of Sayyida Sakinah, daughter of the Shiite saint Hussein, son of Imam Ali. By then, the conflict seems to have worn him down: He began looking fatigued, and he seems to have been drinking even more than before. But he was not yet done. In the summer of 2012, he was redeployed to Deir ez-Zor province.

Khizam committed some of his worst massacres on an iconic suspension bridge situated by the Euphrates river in the eastern city of Deir ez-Zor. Known simply as Deir among the locals, the city’s students, civil servants, underemployed, tribal and professional groups began demonstrating in large numbers from early April 2011. The initial repression came from the usual mix of police and Shabbiha militias, but as the protests continued and intensified, local soldiers defected and used light arms to defend their neighborhoods. It wasn’t long before these loose squads began to organize and develop offensive strategies like the FSA, to which the regime responded by sending in their heavy guns.

In late September 2012, the regime dispatched the 105th Republican Guard brigade, led by Zahreddin. Khizam, as usual, followed in Zahreddin’s footsteps, and there is footage of them sitting around in a Bedouin tent. They stormed the city on Sept. 25 with approximately 2,400 troops and armored equipment, including 150 heavy vehicles, mostly tanks and amphibious vehicles. According to eyewitnesses, advising officers from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard were also present during the entire exercise. Videos show the combative and boisterous group yelling slogans, such as “God, Syria, Bashar, the Guards, and that’s it!”

Zahreddin and Khizam’s men seemed to be preparing for a major battle, but the FSA realized it was outnumbered and retreated further east. The FSA’s civilian support networks and infrastructure was now exposed to the onslaught of the Republican Guard, which sealed off the western neighborhood of al-Joura and shelled it randomly. It is here that Khizam began detaining civilians entering or leaving Deir ez-Zor and used them as human shields to enter the neighborhood. Consequently, the occupation of al-Joura was easy, with little or no armed resistance by the FSA.

The massacres that Khizam’s men carried out in al-Joura and the adjacent neighborhood of al-Qusoor were a one-sided mass killing campaign that was most intense that morning of Sept. 25 but lasted several days. Virtually all testimonies from locals who witnessed the massacre paint a consistent picture of methodical, purposeful killings: Republican Guards fighters cleared houses one by one, lined up civilians along the walls and executed them with handguns or AK-47s.

According to the testimony of one survivor, Khizam personally conducted executions of civilians:

“There was a house used as a store of medicines by opposition factions in al-Qusour neighborhood. The house was rented by Ashraf Al-Jaijan. He was arrested by government forces. Ali Khizam, an official within [the] Republican Guard[s], investigated him along with five detainees in a house in the neighborhood. Khizam forced the household to remain in a room until he finishes investigation. Ashraf was executed during investigation on Oct. 2, 2012.”

One man, who happened to visit from the city of Raqqa the night before, was apprehended by Zahreddin and forced to hand over his car keys. While Zahreddin was busy familiarizing himself with the car, the man ran off and escaped an otherwise certain execution.

Thaer from al-Qusoor neighborhood recalled how his neighbor Abu Ammar was caught looking at Khizam’s group from his balcony:

“Large groups entered our neighborhood and began their search. After they finished searching our house, I heard one of the officers shouting to our neighbor Abu Ammar: ‘Come the fuck over here!’ Abu Ammar came down. I could hear well what was going on: ‘Get the fuck down on the ground!’ Then I heard a burst of bullets. … Their forces withdrew at night so we found Abu Ammar’s body. His only fault was that he looked at them from the balcony.”

The victims of the al-Joura massacre included upper-class professionals such as Dr. Haidar al-Fandi, who was in charge of a field hospital in al-Joura neighborhood, and clergy like local imam Amin Mohammad al-Salameh. But most were ordinary men, women and children. In many cases, entire families were shot at close range in their living rooms or on the sidewalks in front of their houses. The victims’ exit wounds were often in their faces: foreheads, cheeks and eyes. Anyone who dared to return to bury the bodies strewn across the neighborhood was arrested and summarily executed.

Video footage of that day corroborate the testimonies. Three videos stand out as particularly informative about what happened before, during, and after the Deir ez-Zor massacre. One video shows how, upon entrance to the neighborhood, in order to clear the streets, the Guards’ snipers kill anything in their sight. Three unarmed men are killed when their car is shot at, as they bleed out on the dusty pavement. Panic breaks out as women scream and wounded people are rushed to the hospital. Another video shows the Republican Guards, recognizable from their red patches, gathering old and young men alike, in some cases teenagers, and lining them up in front of a wall. Mirabo al-Aqel laughs as he makes them chant pro-regime slogans: “Who is your boss?” The men chant in unison: “Bashar al-Assad!” The cameras are then turned off, and the detainees are executed.

But Deir el-Zor became Khizam’s last stand. According to various sources, on Oct. 1, 2012, a sniper of the Hamza bin Abdul Mutallib Brigade shot him in the head during fighting in Deir ez-Zor. Regime officials then kept his body in a morgue and, for myth-making purposes, delayed the announcement of his death for five days to coincide with the anniversary of the start of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. According to another version, he was wounded by a sniper shot, was rushed to a military hospital in Damascus and died there.

Khizam rampaged through Syria in ways reminiscent of Maximilian Aue, the SS officer who plays the protagonist in Jonathan Littell’s novel “The Kindly Ones.” (Littell, coincidentally, was in Homs when the regime launched its onslaught and wrote a powerful report of the siege and the violence.) Khizam’s legacy of sectarian violence had a profound effect on the course of the Syrian conflict. He committed massacres in Ghouta, Homs and Deir el-Zor to punish rebellious communities, to avenge the regime’s military failures, and thereby made a major contribution to the regime’s deliberate strategy to stoke sectarianization against Sunnis.

Despite the Assad regime’s officially secular nature, the Alawite religion, as institution, eschatology, theology, and as collective and personal experience, inspired warrior-sheikhs like Khizam. This would have normalized mass murder for them by otherizing Sunnis and rationalizing annihilation. In this way, Alawite warrior-sheikhs like Khizam were no different from other religious perpetrators, “arguing that they were members of a superior people chosen for a special mission, identified that superiority and mission with their membership in religious institutions, or pseudo-religious racial or ethnic orders or castes.”

After his death, Khizam’s body was flown from Damascus to Latakia airport by military airplane and driven to Qardaha. Huge crowds poured into the streets for his state funeral, women ululating and Republican Guards standing to attention in a spectacle carefully stage-managed by regime propagandists.

At his funeral, his brother Fawaz, also an Alawite sheikh, said: “We have nothing but pride, honor and heavenly generosity in the martyrdom of our dear and beloved brother, Ali, because he honored us with his life.” His marble tombstone was simple and featured a famous photo of him staring into the camera lens, undaunted and piercing. After his death, the regime proceeded to sanctify him, by honoring him in a ceremony at the Assad Library.

The pro-regime television channel Suriya TV produced a hagiographic documentary called “The Secrets of Steadfastness,” which served to further the myth of Khizam by sacralizing his memory. His family and friends repeat Baathist and pro-Assad mantras about his “patriotism” and “struggle against terrorism.” His son Haidar is seen sitting in the living room with his father’s military cap on and his automatic weapon on his lap. His daughter Batoul is seen crying at his grave and remembering how great a father he was, and even Khizam’s elderly mother is dragged in front of the cameras to extol her son’s virtues and faithfulness. There are no sectarian references, and the word “Alawite” is not used anywhere in the carefully choreographed film, which served as a message from the regime to continue to secure the loyalty of the Alawite community.

The story of Khizam is not unique: It is representative of a subset of Alawite sheikhs who not only supported the regime in 2011 but also took up arms and mobilized to repress the uprising. Their anxieties as minority religious leaders impelled them to commit violence they may have believed was defensive in nature, on the basis that it would prevent future violence against their sect. This anticipatory or preemptive violence became a self-fulfilling prophecy; indeed it radicalized many victims and their communities and ultimately drew retributive violence. After 11 long years of conflict, the failure of this approach is clear to all: There have been no winners, in any sect.