On a damp, pale afternoon in mid-January, a few dozen young men stood outside a gutted farmhouse on the outskirts of Horgos, a Serbian village on the Hungarian border. Most came from Algeria and Morocco. Most had gone days without a proper meal or a change of clothes. Everyone had tried several times to pass through Hungary and travel elsewhere in the European Union. Everyone said Hungarian border police had clubbed them with batons, detained them and forced them back across the border.

Less than 2 miles away, the Hungarian border was lined with two rows of tall fencing, each adorned with tight coils of razor wire, fitted with surveillance cameras and monitored from watchtowers. Up and down the line, there were others like the men in the farmhouse, groups holed up in the husks of abandoned buildings, waiting for their next opportunity to try to slip past Hungarian patrols. When that moment arrived, they plodded through the fields toward the fence as stealthily as they could, mud caking to their boots.

At the farmhouse, the men hugged themselves against the cold and described the violence they had endured along the way. Some said Bulgarian police had tased them and stolen their belongings — cash, clothes and food. Others recalled Greek border guards beating them, stripping them and pushing them back into Turkey. Most had already tried, and failed, to leave Serbia via the Croatian border.

Hussein had made the journey from Algeria to Turkey and, from there, struggled across the Balkan trail on crutches, a thick wrap of gauze around his right foot. During a recent crossing, he said, Hungarian border guards snatched him, smacked his foot with a baton and confiscated his phone. “The conditions here are hard,” he admitted.

In the meantime, he had no choice but to stay behind while the others kept trying to push onward. He didn’t think his foot was broken — just fractured, he guessed — but he could not put any weight on it for now. With any luck, he hoped, he would be well enough to cross again within a week’s time. “Every day, it’s getting a little bit better,” he said.

What the men there were experiencing isn’t rare. For many refugees and migrants, Europe’s borders have become synonymous with violence and extrajudicial expulsions, known as pushbacks, in recent years. Bulgarian, Croatian, Greek and Hungarian authorities, among others, stand accused of beatings, threats and summary expulsions. From the beginning of 2016 to July 2021, the Hungarian authorities carried out some 72,000 pushbacks, according to the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, citing the country’s official police statistics.

In the farmhouse’s empty window frames, the men had strung up blankets to protect against the wind. Whenever rain fell, water dripped through the holes in the sagging rooftop. Inside, it reeked of mildew. A handful of men walked through the concrete innards of the home, pointing to the wadded-up blankets strewn across the dirt floor. They slept, about a dozen to a room, huddled together near small fires and coughing through the night as smoke filled the place.

Outside, a rush of wind scattered empty cans and plastic grocery sacks across the yard. Clothes and blankets hung limp, drying on a rusted iron fence. One tried without luck to light a campfire with wet twigs. A few chatted with their families back home on video calls. Some had layers of plastic wrap around their legs and shoes to keep dry. Others said their phones had died; without electricity, their only option was to walk the 30 or so minutes to the heart of the village and pay a store attendant a few euros to let them recharge.

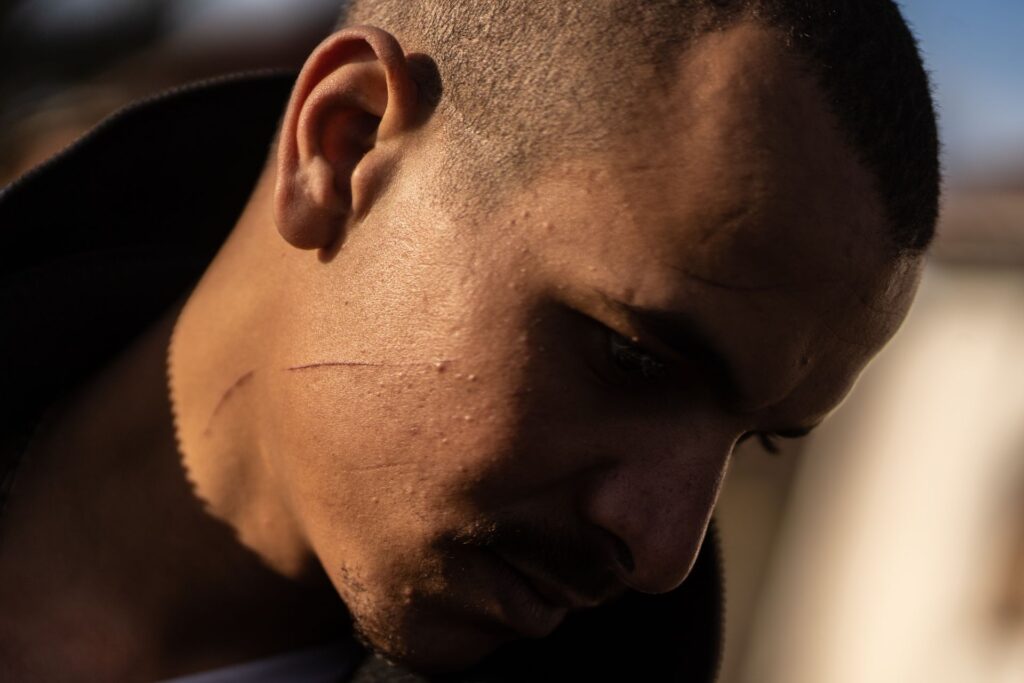

Anything, even a baton to the head and a boot to the ribs, can become routine. A young Moroccan man pulled his hair aside to reveal a lump on his skull: A Hungarian border guard had hit him, he said. Another tilted his head to show scratches on his face: He had been cut on the concertina wire crowning Hungary’s border fence. Yet another said Hungarian guards shoved them to the ground, kicked them, stole their phones and belongings. Sometimes, they said, Hungarian police posed for photos after apprehending them. “It’s like they’re happy they just caught an animal,” said Mohammed, 22, from Algeria.

Mohammed lifted his phone and found a photo of himself back in Algeria more than two years earlier. He had worked as a barber, and the face in the photo was fuller than it was now. He guessed that he had lost between 50 and 60 pounds. The way he told it, Greek authorities had pushed him back 10 times on that country’s land border with Turkey. He said he had passed into Hungary 11 times. He still believed he would make it to Western Europe but, in the meantime, he had “nothing to do but stand by the fire here and wait.”

Hungary’s southern border with Serbia zigzags across more than 100 miles of mostly flatlands. On its eastern tip, the border runs into Romania. On the western edge, the border collides with Croatia, where authorities have also used pushbacks to expel refugees and migrants. Last year, Frontex, the EU’s external border agency, documented more than 330,000 “irregular” crossings on the EU’s external borders, the highest number since 2016. Of that total, nearly half took place in the western Balkans.

When the number of refugees and migrants reaching Europe spiked in 2015, fueled by armed conflict in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as economic corrosion elsewhere, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban spearheaded a campaign of conspiracy theories and ultranationalist rhetoric against refugees and migrants. An EU member since 2004, Hungary started construction of a fence on its Serbian border in July 2015. (Another fence arose on Hungary’s border with Croatia, and a second row of fencing was completed along the Serbian line in 2017.) In July 2016, Hungary effectively legalized pushbacks by permitting the expulsion of anyone caught within 5 miles of the Serbian and Croatian borders. Last September, Hungary launched so-called border-hunter units, a part of the police force that Orban said would “protect the motherland against migration.”

But pushbacks across the continent have also prompted widespread criticism from rights groups, watchdogs and some European politicians. Hans Leijtens, the executive director of Frontex, recently vowed to end illegal pushbacks.

For its part, Hungary has shown no sign of letting up. In December 2020, the Court of Justice of the EU ruled that Hungary’s pushbacks violated European law. In 2021, despite allegations of Frontex’s own involvement in pushbacks in some countries, the border agency announced it had suspended operations in Hungary over such abuses. In December, the European Court of Human Rights said Hungary had violated procedural obligations by rejecting applications submitted by some asylum seekers and forcing them back into Serbia. In early February, the European Court of Human Rights ruled against Hungary again. Among other infractions, the court said Hungary had failed to protect the life of a Syrian man who was allegedly pushed back and then drowned in a river.

A Hungarian government spokesperson dismissed reports of pushbacks and police violence as attempts “to discredit personnel on duty at the border.” By email, the spokesperson insisted that Hungarian authorities had violated neither EU nor Hungarian law. “The police are performing their duties lawfully, professionally, and proportionately, and they place special emphasis on treating migrants humanely and with respect for their human dignity,” the spokesperson said. “Migrants on Hungary’s borders are not being harassed, and the significant numbers of unaccompanied minors who have been arriving are being provided with protection, healthcare, and education.”

A European Commission migration spokesperson confirmed: “The EU Commission’s position on pushbacks is clear — efficient border management must be firmly rooted in the respect of human dignity and of the principle of non-refoulement.” Citing a “close dialogue” with EU member states, including Hungary, the spokesperson said the commission “expects national authorities to investigate any [allegations of] pushbacks and violence.”

Meanwhile, in late January, the commission renewed a push for the implementation of a new bloc-wide migration plan. Dubbed the New Pact on Migration and Asylum, the proposal aims to ramp up “more effective returns” and serve as a “deterrent” to irregular border crossings. “Those that are in need of international protection should be always welcomed in the EU and given … protection,” the spokesperson added. “Those that are not in need of international protection have to return to the country of origin in a humane, effective, and sustainable way.” The pact was adopted in 2020 but has yet to be implemented.

As Hungary and other EU countries continue to carry out pushbacks, Zsolt Szekeres, a senior legal officer at the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, worried that Europe’s focus on deterrence “is not going to work; in fact, it’s only going to create more violence and tension on both sides of the border.”

Szekeres also feared that deterrence would continue to push people into more dangerous crossings while leaving them even more dependent on smuggling gangs. “The people who need the protection — vulnerable people, children, single women, torture survivors — are going to be left without help,” he said. “That’s inherently antidemocratic and anti-European.”

On a frigid day in January, Srdjan Popovic opened the door of Info Park, a Belgrade-based humanitarian group, and welcomed a group of young Afghan men who had appeared outside. He offered them a place to sit at a dinner table, prepared tea, and microwaved a cup of instant noodles for each. It was only 2 p.m., but more than 40 people had already stopped by Info Park’s office.

In 2022, Serbian authorities documented 124,127 new arrivals, more than twice the total number of those who made it to Serbia the year before. Last year, more than a third came from Afghanistan, while a little more than 29% of them had fled Syria.

As arrivals swelled in recent months, Popovic explained, Serbian police had clamped down on informal migrant squats in the capital and along the borders. In late November, the country’s Ministry of Internal Affairs announced that police raided several informal camps near the Hungarian border, detaining hundreds after a reported shootout between small groups of migrants. A handful were arrested, while most were hauled back to official camps.

Many of those who show up at Info Park have been roughed up, subjected to electroshocks or bitten by police dogs in Bulgaria. “Maybe every day we have reports about the violence of Bulgarian police,” said Popovic. Now and then, Info Park volunteers travel to the borderlands near Horgos to deliver aid, where they inevitably hear more stories of pushbacks and beatings by Hungarian border police.

As Popovic spoke, an Algerian woman named Sofia came in. She said she had first traveled to Turkey, walked across Bulgaria, and finally reached Serbia. She hoped to reach France but, along the way, Bulgarian police struck her with batons while they briefly detained her. “It was very difficult,” she said. “But what can we do? There are even more difficult situations we could be in.” Later, as she prepared to leave, she added, “If I ever make it to France, I’ll need psychological treatment.”

Back at the farmhouse in Horgos, the clouds grew thick with rain. A few men moved around in place to stay warm. Humanitarians had dropped by with food earlier that afternoon, but everyone was still exhausted.

Mahdi, 21, from Morocco, had another problem: He didn’t know the English word for his illness. He had shown his medicine to doctors in a Serbian refugee camp, he said, but they hadn’t figured out that he had a chronic form of leukemia. Three years ago, a doctor in Morocco had diagnosed him, and he hoped to reach Germany or another Western European country, where he thought he would have the best chance at receiving adequate treatment.

Mahdi might have had it the worst, but no one at the farmhouse had managed to stay healthy. When another handful of humanitarians showed up to provide basic medical assistance, the young men crowded around them, shivering. Some complained of fevers, some of sore throats and chest-rattling coughs, most of chronic fatigue.

Beginning shortly before 5 that afternoon, nighttime dropped fast and heavy as darkness unrolled like a carpet and shadows swallowed the interior of the farmhouse. While a couple of men beyond him finally managed to light a fire, Mahdi explained that he had never had his heart set on living outside Morocco. “My parents and my family are there,” he said. “I don’t want to make problems [in Europe]. I don’t want to stay in their countries. I just want to get treatment.”

On a recent crossing, he recalled, Hungarian border guards had beaten him, pushed him back and confiscated much of his medicine. It’s the last part that bothered him the most. “What do they even want with my medicine?” he asked. He pulled a sleeve of pills out of his jacket pocket, a small stash he had managed to hang onto. He had enough to last six more days, but he worried that he wouldn’t be able to get more before the supply ran out. Sick or not, he had no plans to turn back. “You get hurt, but you get used to it,” he said of crossing. Still, he admitted, “It’s difficult.”

Later, a man emerged from the farmhouse with a mouse cupped in his palms, then let it loose in the field. Mice and rats, the others explained, sometimes skittered across their sleeping pallets. After a while, police lights flashed on the highway in the distance. Those who had stuck around outside now darted into the house to hide. But when the police car had cruised past, they gradually reemerged.

Rain started to fall, and Mohammed, the former barber from Algeria, came back outside. A night earlier, he and others had approached the border, where, through the fence, they spotted Hungarian border police waiting. In the end, Mohammed and the other men turned around and returned to the farmhouse. In the beginning, he said, they used to fear getting caught on the border. “Now, we don’t,” he said. “You get used to the hits and you don’t feel it. And when it’s cold, I don’t feel it.”

Sneaking past the border patrols and safely crossing into Hungary wouldn’t be easy. In many spots along the border, flat, muddy fields stretch out for hundreds of yards leading up to the Hungarian fence, and winter has stripped trees of their leafy cover; border guards could likely see them coming from far off. But Mohammed was determined. “All we need is two hours to get through Hungary,” he said, laughing.

But a few moments later, a group of men appeared on the shoulder of the highway across the field, shrouded in mist and trudging back from the border. He pointed their way and shook his head. His fate, he seemed to suggest, was bound to theirs.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.