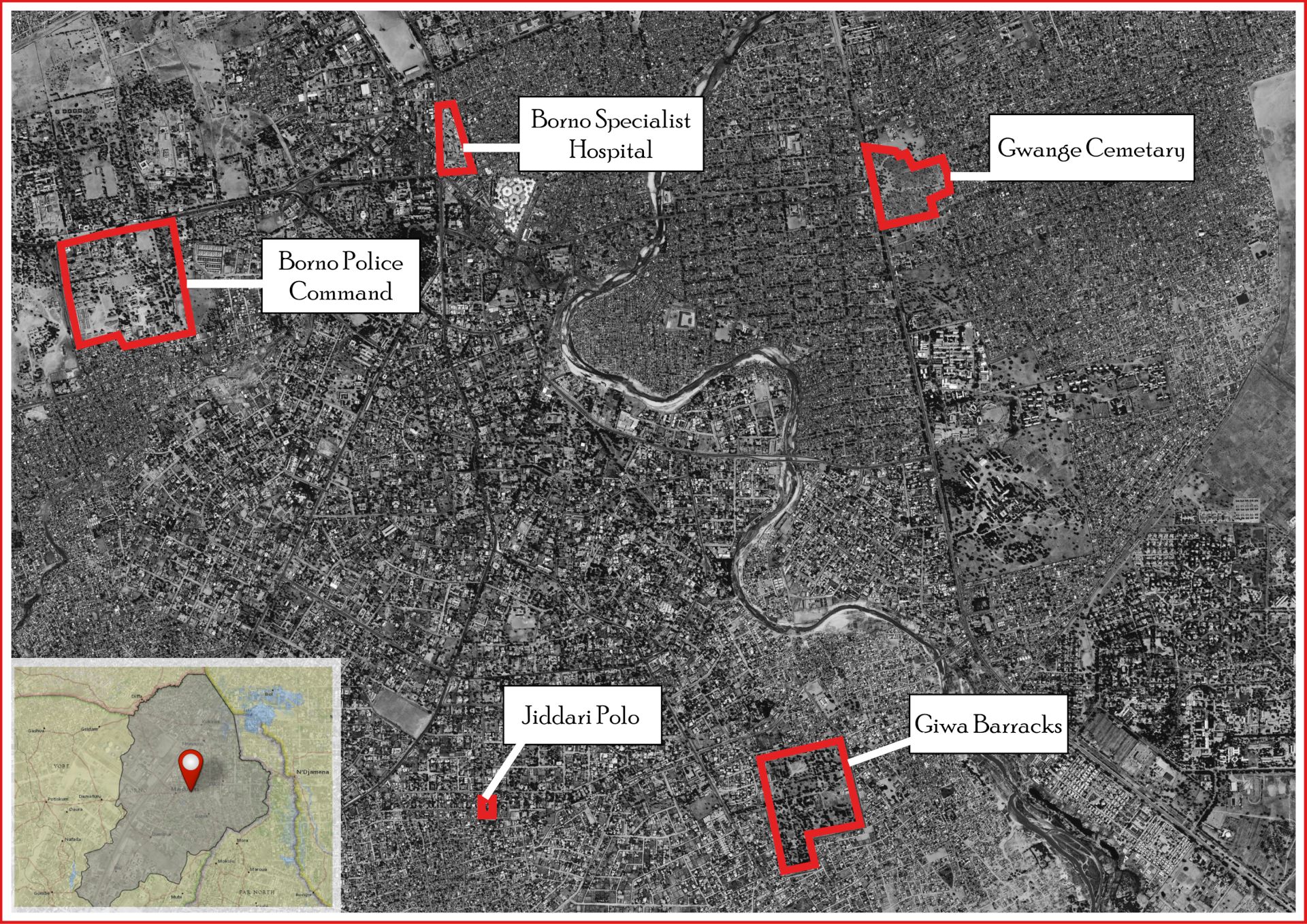

There are more than 25,000 missing people in Nigeria, more than in any other country on the African continent. Many of them disappeared during the height of the Boko Haram crisis, as the Nigerian army fought to keep the Islamist insurgency, which had infiltrated several northern cities, at bay. During that time, thousands of civilians were arrested and detained at the Giwa barracks in the northern city of Maiduguri, suspected of being affiliated with the terrorists; few of them were ever released. A New Lines/HumAngle investigation has uncovered evidence that the Nigerian army undertook a campaign of summary executions, extrajudicial killings and mass burials in Maiduguri during this period, in contravention of international law. (Read the full investigation here.)

These extrajudicial killings during the military counterinsurgency operations in northeast Nigeria were largely undocumented. Because most of them happened years ago, the majority from 2012 to 2018, it is growing increasingly difficult to document them at all. But by combining our on-the-ground reporting with analysis of satellite imagery and the use of other open-source intelligence, we have been able to trace vestiges of these human rights violations. Here is how the process unfolded.

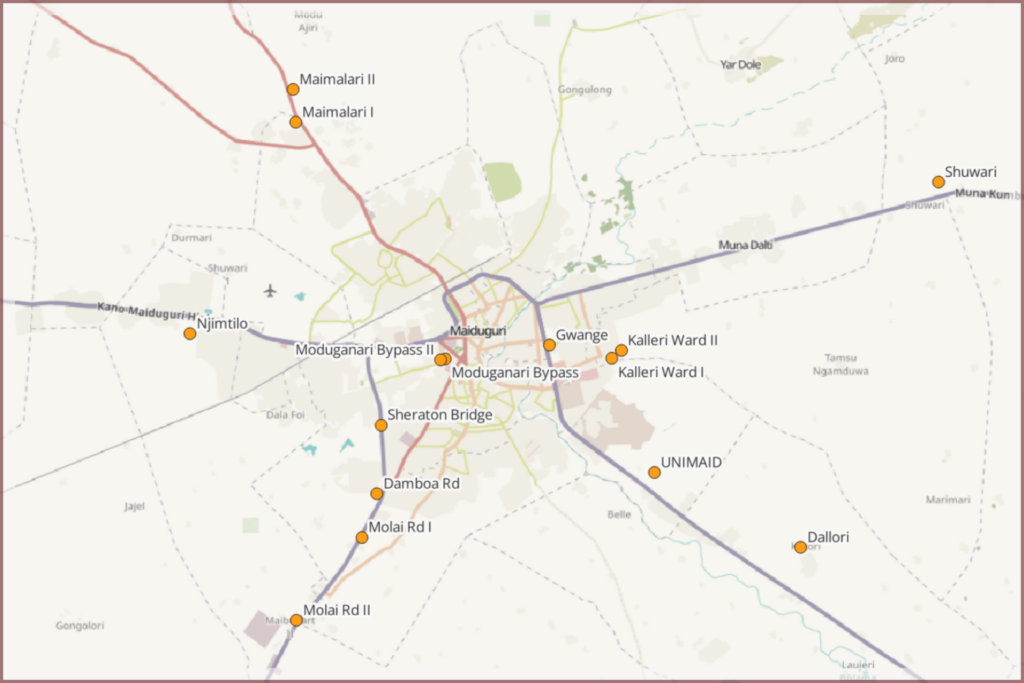

In May this year, New Lines/HumAngle visited 15 sites in Borno State, where the military allegedly buried or dumped bodies of people killed extrajudicially or who died in detention, especially between 2012 and 2015, during the peak of the Boko Haram crisis.

We had access to knowledgeable fixers who took our reporter close to these scenes. We then took pictures and collected supplementary information. We further probed the coordinates using open-source intelligence and geospatial tools, including satellite imagery and data, alongside contextual information.

The sites varied in nature. Some were within the premises of established cemeteries or in the vicinity of established morgues where dead bodies were improperly deposited. Others were secret burial sites where the victims of extrajudicial killings were said to be dumped in open fields or ditches, as well as water sources.

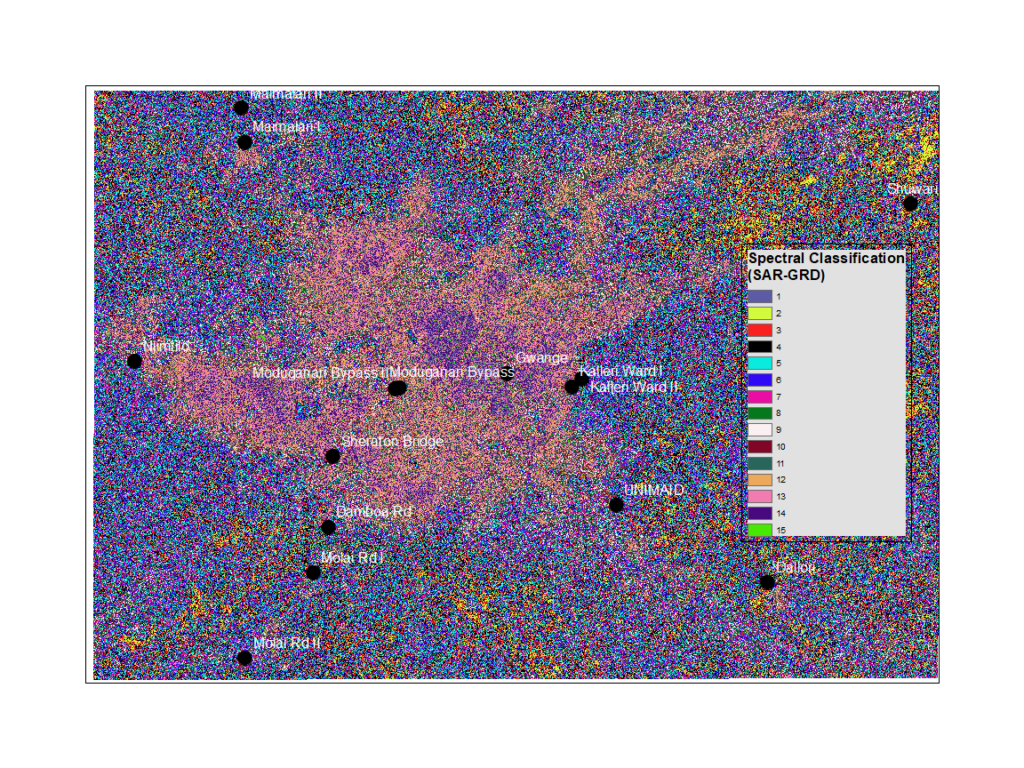

Because of the diverse nature of the locations, we had to rely on various sets of tools and techniques to determine if these were in fact mass burial sites, including archival satellite images, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) sensor data, field coordinate data and other open-source intelligence tools. Another challenge was the absence of high-resolution conventional satellite imagery of the area, especially prior to September 2015, so we had to rely on information from multiple sources, including press reports and witness statements, to corroborate our hypotheses.

For access to SAR satellite data, we used the NASA archives. The NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar mission, a joint Earth observation satellite project between the Indian Space Research Organisation and NASA, delivers cutting-edge radar imaging data for the study of diverse Earth processes, including land deformation, landslides, earthquakes, volcanoes, soil moisture, ice sheet dynamics and ecosystem changes.

Unlike conventional satellites that make use of light, SAR satellites employ microwave energy for imaging purposes. This unique technology enables the collection of a specific type of sensor data known as ground range detection. The satellite is designed to detect surface changes as well as subtle variations occurring a few feet below the ground surface.

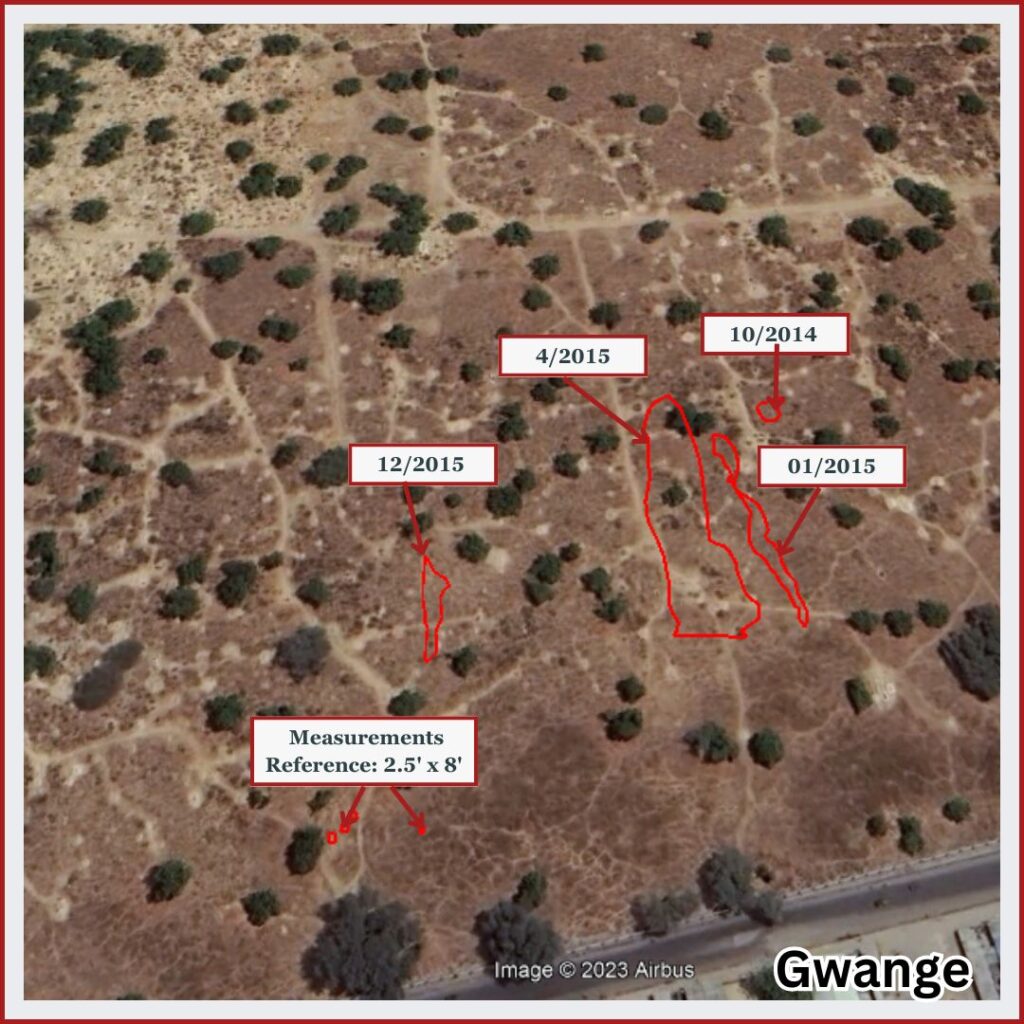

Using this method, we were able to estimate some levels of altered soil profile deformation, even if they were not readily visible on the surface. To achieve this, the measurements were calibrated based on known burial sites such as the Gwange and Kululluri cemeteries in Maiduguri. This allowed us to create baseline measurements — similar to a control variable in a scientific experiment — in areas close to where our sources claimed people might have been buried.

By comparing the subsurface features of the suspected mass graves with known burial sites, we could measure underground disturbances in many of the locations. Some of these, of course, could have been the result of other natural or artificial disturbances, but the combination of data sources heightened our confidence in the assessment.

We expected the army to deny these allegations, and were concerned that reporting our suspicions would alert them to the sites, which they could have taken steps to remove or make inaccessible. Once we finished our investigation, we put our findings to both the army and the Civilian Joint Task Force. Neither returned our requests for comment, despite multiple attempts.

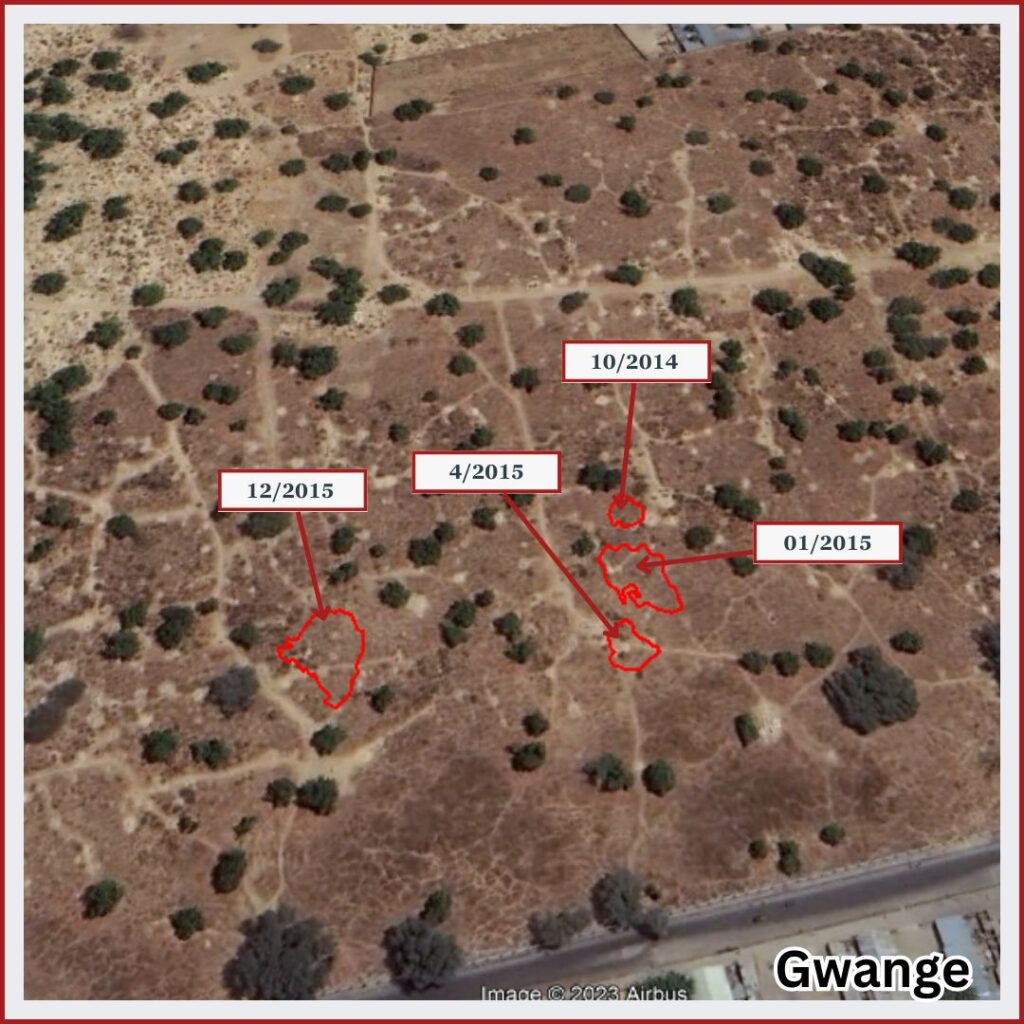

Our sources in Maiduguri attested to the burial of people brought by the military to Gwange cemetery in mass graves. Because it’s an established burial ground and not a good place to search for specific sites, we first tried to find the alleged mass graves in the section suggested to us. We used the SAR near-surface scan of the area from April 2015, as sources said the incidents occurred from 2013 to 2015.

The benefit of studying the subsurface disturbance of Gwange was twofold. First, it helped to train our radar satellite computations to measure what near-surface underground disturbances look like in known burial sites — corroborated with evidence of surface gravesites. We could then use that as a reference for studying other potential sites where conventional data was unavailable. The second reason was to find the probable site of a mass burial reported in the cemetery in 2014-15.

This is shown in the above images, along with the disturbed area and its coordinates.

Our sources gave a detailed description of this site, corroborated by other studies looking at the same issue by organizations such as Amnesty International. Using the radar measurements, the marker in the image above recognized probable underground disturbance in that year to suggest the burial location.

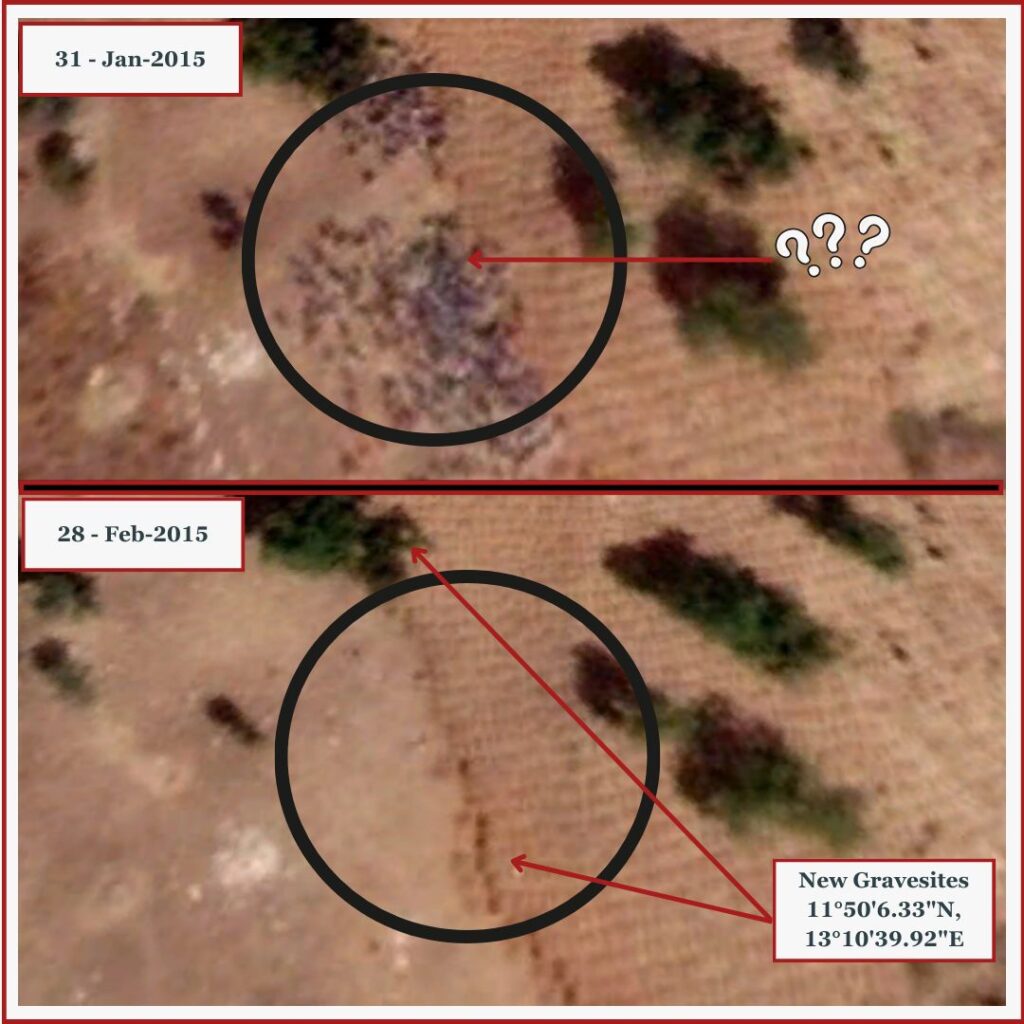

A closer observation of available satellite imagery of the area also showed a noteworthy “unusual coagulation” within the cemetery grounds, strongly suggesting heaps of dead bodies brought for multiple mass burials.

A Guardian report from 2016 mentioned multiple fresh graves dug by cemetery workers at the behest of the military, who brought garbage trucks of alleged Boko Haram fatalities. The report contains ground photos of numerous burial sites dug at the time. Geolocating these photos matched them to the appearance of the gravesites near the “unusual coagulation.”

Images from Jan. 30, 2015, and April 28, 2015, showed these piles of bodies in the southeastern part of the cemetery. The bodies disappeared about a month later, as shown by Google Earth imagery, and were replaced by fresh gravesites. This tracks with source reports of the army offloading hundreds of dead bodies in the cemetery around the same time of year and suggests they had done the same thing in previous years, including on Aug. 30, 2014.

We also confirmed the claim in the Guardian report that the area was cleared of grasses and prepared for multiple internments in mid-2014. Soon afterward, new gravesites appeared.

Google satellite photos captured a similar chain of events in April 2015. The “unusual coagulation” could not be regular townsfolk because of its sheer size and the fact that no similar incidents occurred in other years — which is also clear from more recent images. Importantly, the images were captured at 1 a.m. over multiple days, reducing the likelihood that the “heaps” were a living crowd standing on the burial grounds.

This pattern of “heaps” on the ground was present at other sites we studied, including an area in the Borno State Specialist Hospital. Higher-resolution imagery would have been much more conclusive, but a request for such imagery proved futile because there was no high-resolution satellite over the area at the time.

Meanwhile, we estimated the number of bodies in those piles using two approaches: the number of fresh gravesites and the mass of the piles.

Based on the measurement of single gravesites from the satellite images at 2.5 feet by 8 feet, we quantified the area of the fresh graves for each year to provide an estimate of their number. We estimated the number of dead by using a standardized pile height of 6.5 feet, multiplied by the average surface area of an adult body (between 17 and 20 square feet). Modest approximations were used. Estimates for April 2015 were harder to get because there may have been additional burials in between the dates of available satellite imagery. We assigned a modest estimate of “at least 250,” but it could have been more than 300 — matching parts of the Guardian report, which suggested that 200 to 400 bodies were taken to the cemetery at the height of the crisis.

Another area of concern was the Borno State Specialist Hospital. New Lines/HumAngle learned from various sources within the hospital and the surrounding community that, in early 2013, the number of bodies brought by the military to the hospital’s morgue became so overwhelming that they had to dump many corpses outside the morgue, which had reached its limit. Past press reports confirmed this too.

Satellite images showed an odd accumulation in the part of the hospital to which our sources directed us. This appearance matches the timing corroborated by our fixer and news reports.

Eventually, the bodies were removed. The trail of satellite images showed changes in the nature of the substances, possibly reflecting the evacuation.

However, succeeding images until late 2015 showed that the area continued to receive a different type of deposit. Our educated guess is that the area served as a waste dump, at first for bodies and medical and solid waste, then just for medical waste, before being cleared early in 2016 and renovated alongside nearby facilities.

The mass in the image above covers an area of 1,680 square feet behind the morgue. We estimate that it could fit about 78 bodies and potentially as many as 300, if the bodies were piled on each other near the morgue fence.

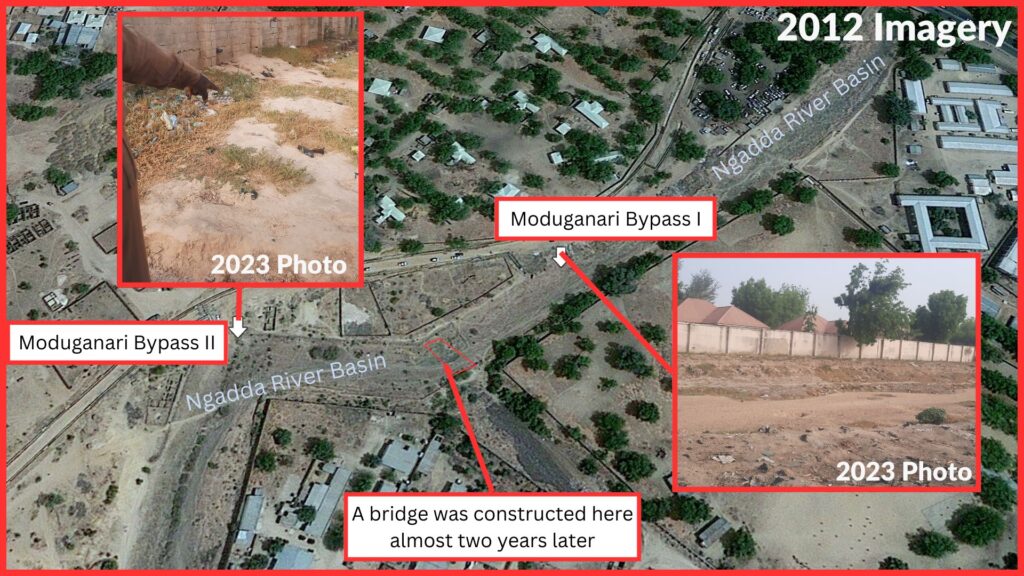

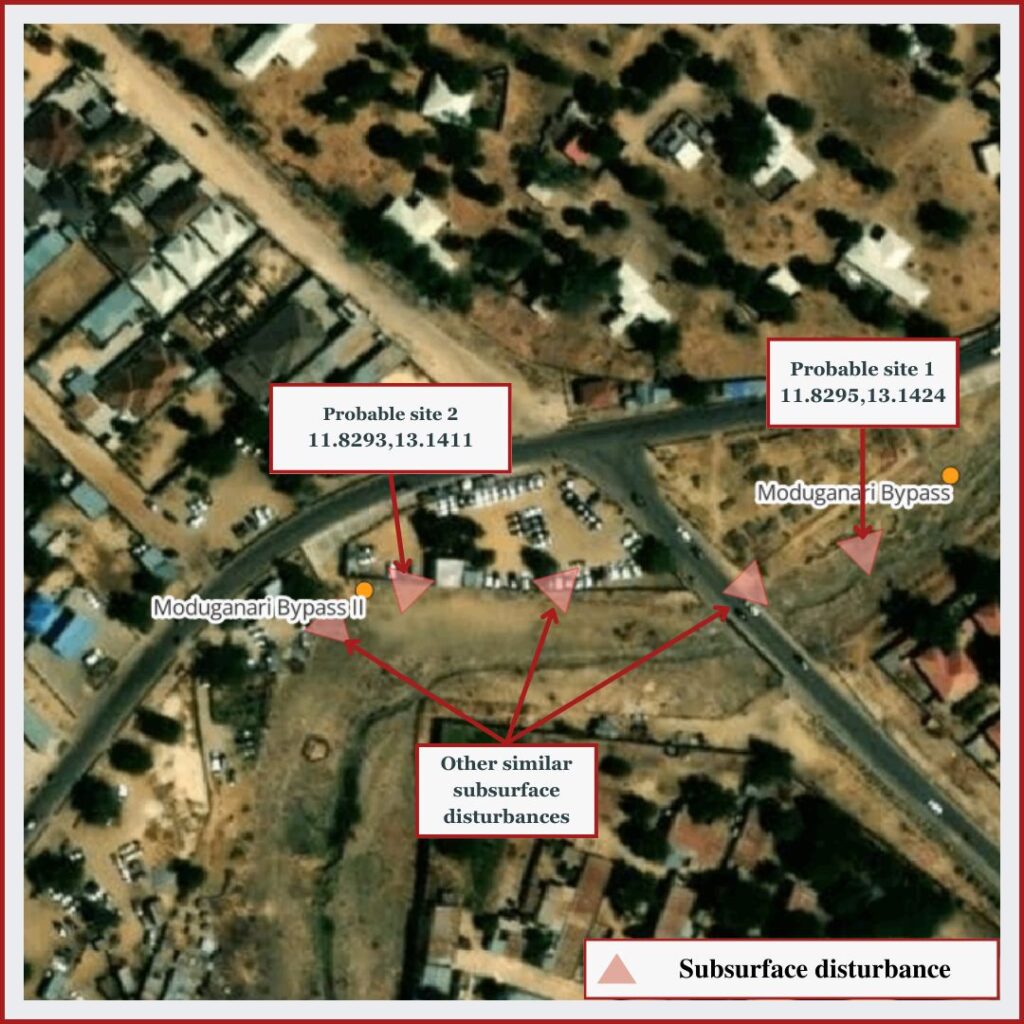

There were other, more informal areas that we looked at as possible mass grave sites, including the Moduganari Bypass, where there were reportedly two human dumping grounds. Today, the sites are located along a seasonal 10-feet-deep basin channel of the Ngadda River. It hasn’t always been a water channel; years ago, it was mostly a thinly forested area with the occasional flow of water. Satellite images of the area show that the channel has become more pronounced over time.

We arbitrarily named the two sites Moduganari Bypass I and Moduganari Bypass II. Our source, who lived close to the sites, says about 70 bodies were buried in Moduganari Bypass I alone and then over 100 in Moduganari Bypass II. The illustration below shows the two most likely points along the channel as well as the less likely candidates.

The spectral classification of near-surface disruptions found the two likely sites and other similar areas. The sites marked with the coordinates are most likely to be the spots where the bodies were buried in 2012. The disturbed subsurface area, especially in Moduganari II, directly matched where our source pointed to.

We found other sites where sources indicated that bodies had been buried, but because of topography and surface disturbances, combined with constant exposure to the elements — some were shallow ditches that filled with water part of the year — making concrete estimates was impossible.

Identifying these mass graves is just the first step in gaining closure for the families of the hundreds of individuals buried therein. Exhumation and identification would need to follow, but before any of that work could commence, the government would have to acknowledge the presence of these graves, and its role in creating them.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.