I was standing in a room where, 100 years ago, a seance took place. The building had no electricity and the shutters were closed. Through the fading light of a rainy October evening, I could still make out peeling green wallpaper and papier-mache moldings crumbling on the ceiling. Empty shelves lined all four walls but rows of neat labels hinted at their previous contents. The study was otherwise empty. In the corner near the window, the floorboards were slightly lighter in color. That’s where the desk would have been.

A century ago, a group of anxious onlookers huddled around a young girl as she sat at that desk. She was a medium, said to be gifted with the power of communicating with the dead. On that night, she would have the extraordinary task of communicating with one of France’s most renowned astronomers and a dedicated student of the occult: Camille Flammarion. After a lifetime of searching for the truth about ghosts, Flammarion was now the spirit that those he’d left behind were searching for.

The seance started with the medium closing her eyes and going into a trance. The floorboards creaked as the guests shifted their weight and the house settled. At last, she spoke.

She hadn’t made contact with Flammarion but she could feel his presence, she said. He was somewhere between the land of the living and that of the dead, not yet capable of communicating with the outside world. His spirit was, as the man himself had been in many ways, torn between worlds.

As I left the room, I thought I caught a blur of motion out of the corner of my eye. A shiver ran down my spine. It was probably just a long strand of my hair that had fallen briefly in front of my face. Probably.

If I’d ended up in the dusty, moldering study of a long-deceased astronomer in a commuter suburb near Paris on a Saturday night, it’s because I’d fallen down a deep rabbit hole. What started as a routine perusal of the Wikipedia page of the French publisher Ernest Flammarion ended with me knee-deep in the musings of his older brother, Camille.

Born into a working-class family but with a keen, logical mind, Camille Flammarion applied himself to the physical sciences, studying mathematics and astronomy at the Paris Observatory before writing a series of wildly successful pop science books. His 1880 title, “Popular Astronomy: A General Description of the Heavens,” brought the study of the universe — galaxies, black holes, Martian landscapes — to the masses and catapulted Flammarion to international fame. Discussed and debated in salons and laboratories the world over, “Popular Astronomy” made Flammarion into France’s most famous scientist.

Yet there was more to this illustrious man of science and it was his darker side that piqued my interest.

Flammarion was, to put it lightly, obsessed with ghosts. For the better part of his life, he studied paranormal phenomena, hauntings and telepathy as fastidiously as he observed and mapped the stars.

Flammarion’s quest to understand the paranormal lay at a cross section of science and spirituality, influenced by technological advances and religious impulses in equal measure. His dedication to ghost hunting would be his downfall: Flammarion’s paranormal studies would see him blacklisted from the Paris Observatory and rejected by his fellow scientists. By the end of his life, the astronomer was left with little more than his own ghosts.

How could a man of science, who spent his life studying the universe through the lens of a telescope, have fallen under the sway of the occult? What was Flammarion searching for, in the sky, and beyond it?

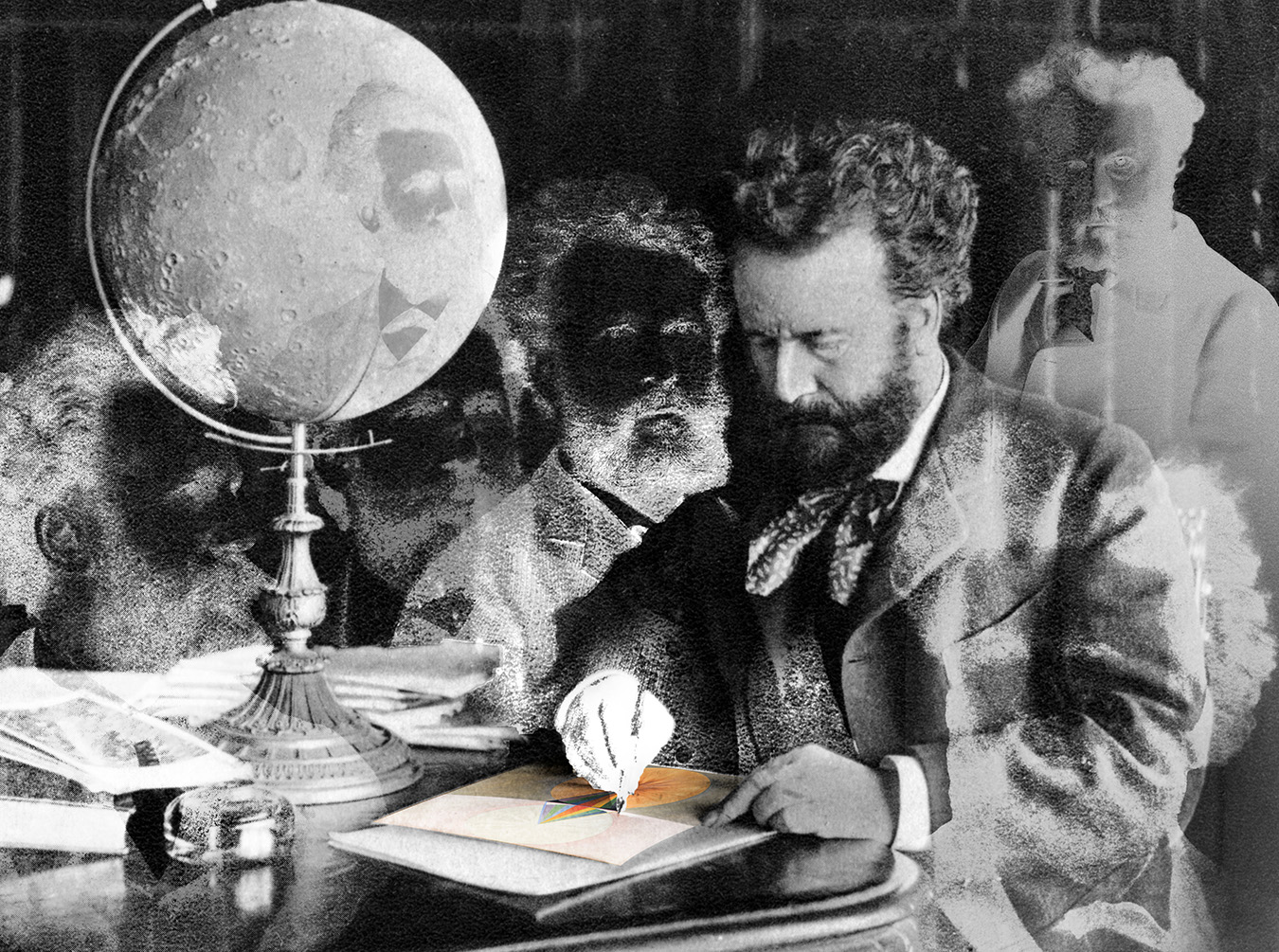

There’s a famous photo of Flammarion. The astronomer, untamed auburn hair parted in the middle, is gripping a table that appears to be levitating. Around him are several well-dressed individuals who, by the looks of it, are genuinely scared. Flammarion stands out from the crowd for his quizzical, if not skeptical look.

It was this photo that initially caught the attention of the French novelist Roland Portiche, who has written a series of historical fiction novels reimagining Flammarion’s life and adventures. “What was shocking was that among the people around the levitating table, there was a reputable astronomer,” Portiche exclaimed when I called him up recently.

Portiche went down the Flammarion rabbit hole, like myself, several years ago. Seeing the photo, he began to wonder: Why was a famous French astronomer, the very symbol of French rationalism at the time, looking into mysterious matters like spiritualism, communication with spirits, haunted houses and UFOs?

“It was a characteristic that was very specific to Camille Flammarion, who was torn between his passion for science and his taste for mystery,” Portiche said.

Part of this dichotomy can be explained through timing. Flammarion came of age at a peculiar moment in history. The mid-19th century was a time of great scientific advancement and innovation that saw the invention of photography and the telegraph and the discovery of the principle behind fiber optics in short succession.

“Ideas, even the craziest inventions, even the most delirious, were able to circulate without scientific censorship felling its ax on the innovators,” the historian Patrick Fuentes has written of the era. “Anything out of the ordinary could advance progress, it was thought; the future would sort it out.”

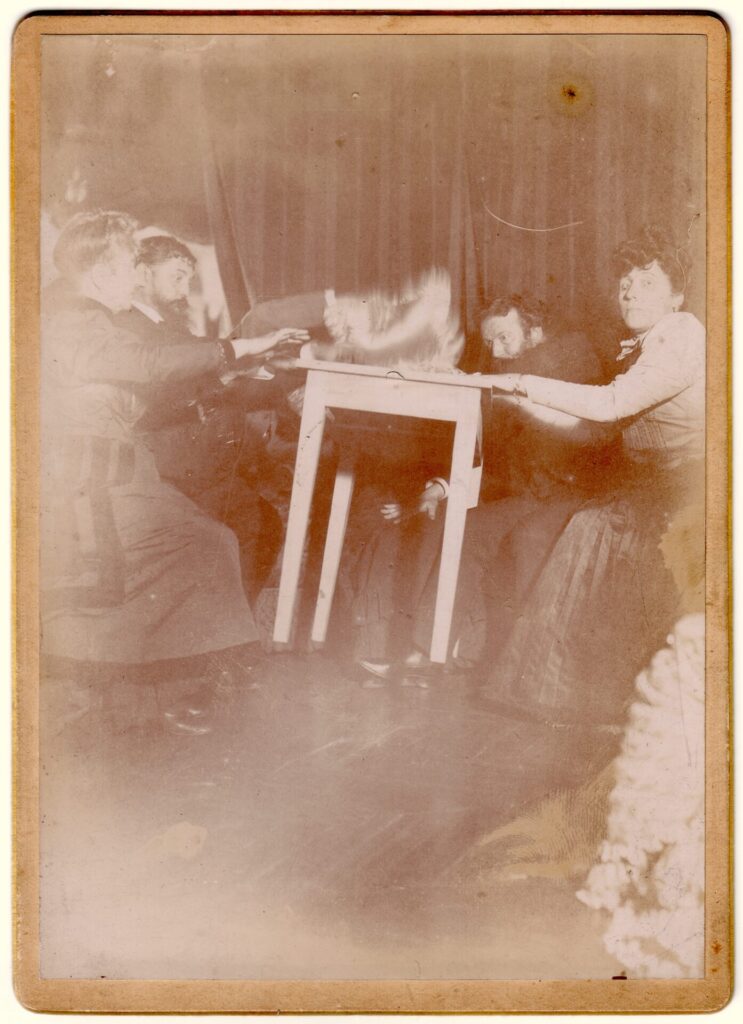

It was also the peak of spiritualism, a belief system holding that spirit mediums could communicate across the divide between the living and the dead. After coalescing in the United States in the 1840s, spiritualism quickly spread to Europe. Seances like the one Flammarion was photographed at, far from being fringe, were wildly popular in elite French circles in the second half of the 19th century. “Table-turning” was particularly in vogue. This activity, which consisted of sitting around a table that appeared to rotate — and sometimes levitate — on its own, attracted very serious French public intellectuals, including the writer and politician Victor Hugo. (Hugo also claimed to have spoken with Shakespeare, Plato, Galileo and Jesus through mediums while in exile on the island of Jersey during the reign of Napoleon III.)

Like many, Flammarion became interested in spiritualism after reading the 1857 bestseller “The Spirits Book,” written by the father of French spiritualism, Allan Kardec. Flammarion was just 15 years old at the time but had already begun working on his first astronomical study, “The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds.” The young astronomer wrote to Kardec, who had imported spiritualism to France after hearing about the Fox sisters, a trio of sisters from upstate New York who claimed to have discovered a method for communicating with the dead. Kardec would become a close friend of Flammarion until the former’s abrupt death in 1869.

Flammarion was intrigued by the spiritualist movement but skeptical, said Philippe Baudouin, a professor at Paris’ Saclay University and author of the recent book “Atlas of Fantastical Paris.” “What interested Flammarion was scientific observation above all else,” Baudouin said. “That is to say, before believing in the reality of a phenomenon, he needed to experience it in the physical sense of the term, in the scientific sense of the term.”

Doing exactly this, Flammarion began to investigate these paranormal trends, attending seances, speaking with mediums and visiting haunted houses across France, jotting down his observations in a series of notebooks that are now housed in the Flammarion archives in Juvisy-sur-Orge.

It’s safe to say that these paranormal studies influenced Flammarion’s early astronomical writings. “The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds” sought to prove the existence of extraterrestrial life. The sequel, “Real and Imaginary Worlds,” then naturally asked whether there is life after death, and if that world might coexist with our own.

When Kardec died, Flammarion was chosen to give his eulogy. In it, he laid out a path that he would follow throughout the rest of his own life.

“Spiritualism is not a religion, but it is a science of which we barely know the ABCs,” he started. “What does the mystery of life consist of? By what connection is the soul attached to the organism? By what manner does it escape? In what form and under what conditions does it exist after death? What memories, what affections does it keep? These are, gentlemen, so many problems which are far from being resolved and which together will constitute the psychological science of the future.”

Unlike other scientists of his time, Flammarion went to great lengths to understand psychic and otherworldly phenomena — leveraging his fame as France’s best-known astronomer to pursue his studies of the occult. But Flammarion’s popular success, and to a certain degree his study of paranormal activity, drove a wedge between himself and the scientific community. “He’s someone who was badly viewed by a certain number of people in the scientific community exactly because he allowed himself to go beyond the bounds of science,” Baudouin explains.

Enrolled at the illustrious Paris Observatory, where he studied under the wing of Urbain Le Verrier, known for the discovery of the planet Venus, Flammarion quickly cut ties with the institution to pursue his own research, deeming the observatory too snooty and technical.

In 1882, a wealthy admirer of his work gifted Flammarion a three-story “maison bourgeoise” near Paris in which to conduct his astronomical observations. Several years later, he had a 16-foot-tall cupola installed on the roof — enough to fit a large telescope.

Today, Flammarion’s house in Juvisy-sur-Orge isn’t on the traditional tourist circuit. In fact, in order to get in, you need an appointment with the manager of the archives at the French Astronomical Society (SAF), who holds one set of keys to the building (the town hall owns the other set and has transformed the gardens into a dog park). But back in the day, this spot drew large crowds. The inauguration of the astronomy tower was so momentous, in fact, that it was attended by the emperor of Brazil.

There would have been less light pollution then, explained Jean Guerard, a volunteer archivist at the SAF, as we toured the grounds of what is now referred to as “Le Chateau.” Despite being in a zone classified as white — the highest possible level of light pollution — the observatory still sometimes offers stargazing sessions to limited groups.

In the archival stacks, located near the chateau, Guerard showed me some of the fan mail Flammarion received. He picked up a bound copy of “Popular Astronomy.” Holding the book with white gloves, he recounted the story of how one female admirer, a foreign countess who called herself Saint Ange, is said to have asked for her own skin to be tanned after her death and bound into the book’s cover.

True or not, the story illustrates how captivating Flammarion’s work was at the time. The astronomer received hundreds of letters from admirers around the world who reached out to him with stories of hauntings and paranormal activity they had witnessed.

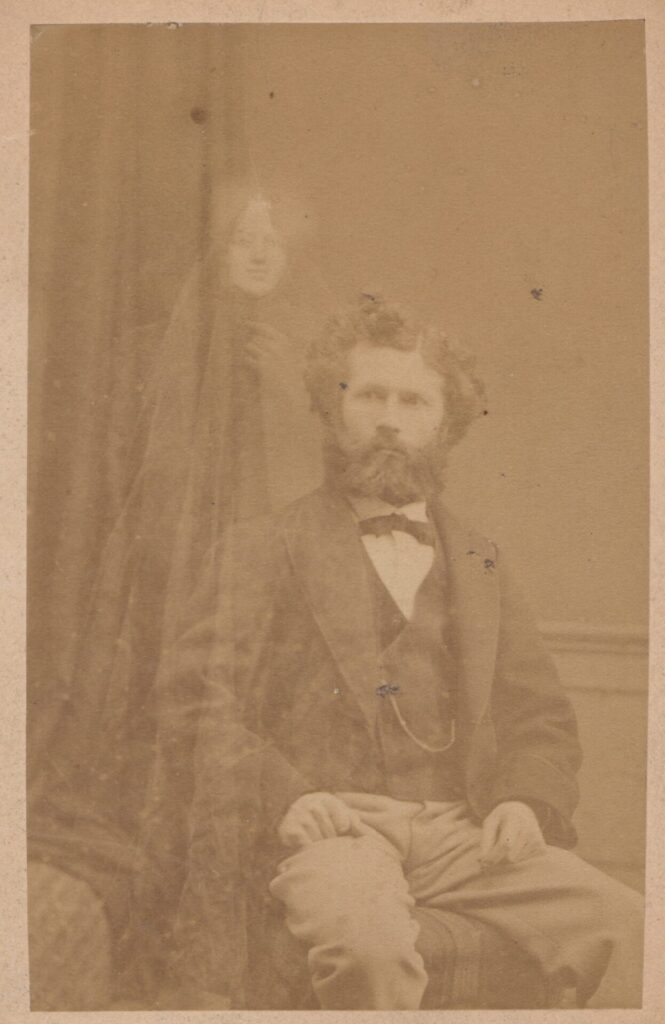

Flammarion began to use this mail as the basis for the spiritualist research he would conduct in the later part of his life, and would turn into his 1909 book “Mysterious Psychic Forces” and his 1924 study on haunted houses, his final work. Starting around the turn of the century, Flammarion regularly invited mediums — including Eusapia Paladino, a famous Nepalese medium — to conduct seances in the living room of his own house.

As Flammarion aged, he came to see the occult a bit more warily. By the end of his life, he had concluded that “exceptionally and rarely the dead do manifest” and that hauntings could be explained by “remote action of the psychic force of a living person.” In sum: Ghosts may be out there, but paranormal phenomena are more plausibly attributed to humans with special powers.

“There’s an evolution in his thinking,” Baudouin said. “Having crossed paths with tricksters, imposters, cheaters, fraudsters in his study of mediums, he became more skeptical, but he never gave up on his studies in this domain until his death in 1925.”

Flammarion himself admitted as much in “Mysterious Psychic Forces.” “Most readers will say: ‘What is there in these studies, anyway?’” Flammarion wrote in the introduction. “The lifting of tables, the moving of various pieces of furniture, the displacement of chairs, the rising and falling of pianos, the blowing about of curtains, mysterious rappings, responses to mental questions, dictations of sentences in reverse order, apparitions of hands, of heads, or of spectral figures—these are only commonplace trivialities or cheap hoaxes, unworthy to occupy the attention of a scientist or scholar. And what would it all prove even if it were true? That kind of thing does not interest us.

“As for me, a humble student of the prodigious problem of the universe, I am only a seeker,” he concluded. “Let us therefore study on, convinced that all sincere research will further the progress of humanity.”

In 1925, the year Flammarion died and was buried at Juvisy, a well-known Scottish author sat down at his study in Edinburgh and began to write. The plot of the novel follows a journalist, Ned Malone, who is assigned to report on the growing popularity of the spiritualist movement in Great Britain.

The title of the book is “The Land of Mist.” Its author: Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes.

In the wake of World War I, as Europe grappled with the immense human toll of the conflict, Doyle found himself drawn to the spiritualist movement, and to the writings of a certain Flammarion.

“Flammarion is cited again and again and again as a credible, reputable man of science, particularly by the man who’s really the world’s greatest proselytizer of spiritualism at this time, who was Arthur Conan Doyle,” Christine Ferguson, a professor of English at the University of Stirling, told me in a Zoom interview.

Ferguson’s research examines the relationship between science, technology and occultism in modern Britain. To her, the legacy of Flammarion’s paranormal studies was not so much scientific as cultural.

“As someone who works on English literature and culture, I’m going to say the biggest impact is on science fiction,” Ferguson said. The paranormal presents a lens “for thinking about things like power, state control,” she continued. “The X-Files and all of those shows that emerged in the second half of the 20th century link the paranormal to ideas of suppressed knowledge and spirits. So it has a huge cultural, artistic, imaginative resonance.”

As I reported this piece, like Doyle’s Ned Malone, I kept trying to understand the amazing attraction of the occult at the time and its relevance, if any, to our modern age. In the end, I realized, it comes down to a question of connection — between humans and beyond humans.

Flammarion would have been fascinated by today’s communication methods — and probably not surprised that I can talk remotely with the moving image of a Scottish researcher. Though we’re living in a drastically more connected, more scientifically advanced world, time has not resolved the deep spiritual and psychic questions Flammarion sought to understand. In fact, these existential questions have only grown.

“During the [COVID-19] pandemic, there was a lot of similar interest in the possibility of maintaining contact at a distance, or thinking about electronic means of continuing to listen to the voices of our dead, whether that may be for recordings or other forms of capture, like keeping someone’s WhatsApp messages,” Ferguson said.

As for the religious movement, spiritualism is still alive and well. It simply migrated. Spiritualism has taken off in places like Brazil and Vietnam, where it is now a respectable, squarely middle-class religion. (In 2020, 6 million Brazilians — or about 3% — identified as spiritualists, making it the third most popular religion in Brazil.) Today, spiritualism is a business worth $2 billion in the U.S., with professional mediums offering the possibility to communicate with the dead. Much as in Flammarion’s era, this business remains replete with scams and frauds.

Nevertheless, there is some interesting innovation going on in this field. Increasingly, mediums are using social media and even video games to connect with new audiences, Ferguson explained. It might also be making a comeback in the West, at least in part as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. An exposition about the spiritualist Swedish artist Hilma af Klint recently drew 600,000 viewers at the Guggenheim. Shannon Taggart, an American photographer, spent 20 years photographing the spiritualist community across the U.S., finding a thriving subculture.

Perhaps what’s missing in today’s version is not only the critical spirit of someone like Flammarion, but also his sense of imagination and his drive to use science to advocate for social justice.

In “Dreams of an Astronomer,” his 1923 book, Flammarion conjured the world of the future — our own.

“There is no frontier. Humanity forms a single family,” Flammarion mused. “Communications are established over the whole globe by a sort of language which passes with the speed of lightning. An administrative council controlled by universal suffrage directs public education, science, art, and justice; and this universal suffrage is enlightened, and exercises its choice among the best and wisest spirits.”

One hundred years later, we remain far from the world Flammarion imagined.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.