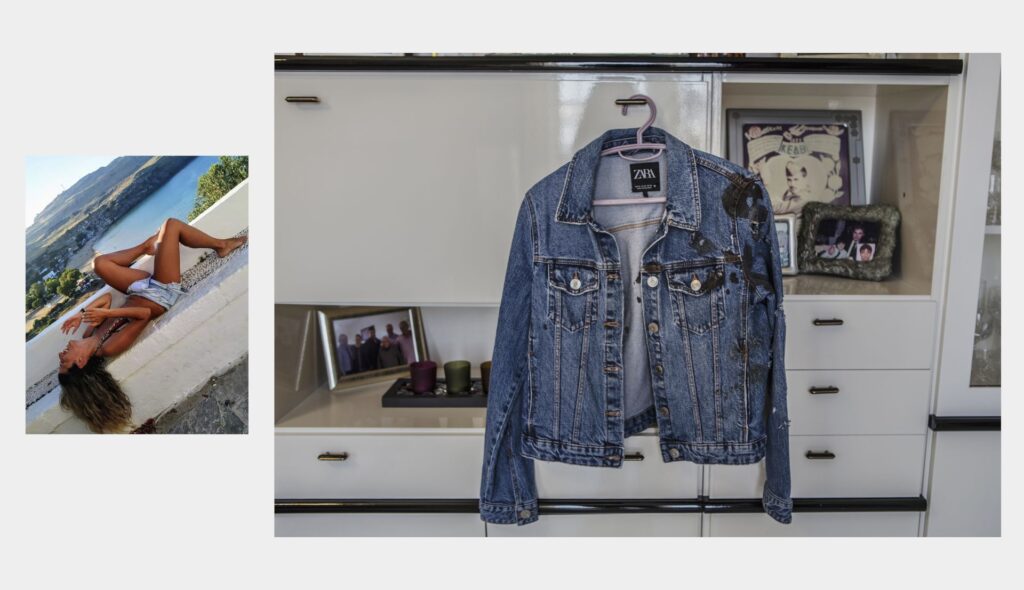

Dora Zacharia’s pastel-yellow family home in Rhodes was always alive with music. She had a rambunctious presence and, from her childhood, her mother Katerina could always tell when Dora was home by her energetic footsteps. She’d get angry when Dora would fall asleep on the couch watching TV or leave coffee mugs and plates lying around. But she would gladly have all the noise and messiness back if she could have more time with her daughter. In September 2021, at the age of 31, Dora was killed by her ex-boyfriend.

In another part of Greece, 10 miles west of Corinth, Aleka Psarakou, 46, smiles as she pulls out a box of old photographs that bring back memories of her 25-year-old daughter Garyfalia. She was “diligent, smart and sensitive,” says Aleka. “It was like someone taught her everything.” Garyfalia never wasted time: She traveled, learned languages, partied with friends, excelled at studies. She trained as a pharmacist in Athens and returned to her family home hoping to open her own pharmacy. She was killed by her boyfriend during their first summer vacation together.

Garyfalia’s and Dora’s tragedies speak to the experience of many young Greek women. But in Greece, there is a common perception that domestic violence mainly affects women in conservative households who are financially dependent on their husbands and thus more vulnerable. While there is indeed a correlation between financial dependency and such incidents, Dora’s and Garyfalia’s experiences show that the problem is much broader. Both were well educated, self-reliant and financially independent, yet they came to similar tragic ends in a country that has struggled to deal with the problem of femicide.

Dora was born and raised in Rhodes, a popular tourist destination with a population of around 50,000. She grew up in a quiet residential suburb outside the medieval town center as part of a close-knit extended family, with parents, siblings, aunts, cousins and grandparents all living together. Dora’s father Triantafyllos Zacharias, who worked seasonally as a driver in the tourism sector, loved music and there would be feasts of seafood while traditional Greek music played. Dora returned to Rhodes to work as a private tutor after completing her studies in Thessaloniki and the U.K. She was particularly dedicated to students with learning disabilities. She met Kostas Moiras, a 40-year-old aluminum installer, through one of her students’ parents. They dated for nine months before moving in together. Dora was excited. But the domestic harmony did not last long and unsavory aspects of Kostas’ behavior soon surfaced. He would try to control Dora’s every move, from attempting to restrict her television viewing to telling her not to sit on the balcony in a short skirt. Dora also suspected that he was monitoring her phone. Kostas became increasingly possessive, demanding that Dora sever ties with her friends and family to spend more time with him.

After two months of intensifying arguments and fights, Dora could not bear it any longer and returned to her family home. The breakup brought a degree of normalcy, but Dora concealed the reason for her return. Her family in turn gave her space and avoided asking her questions. But Kostas remained a menacing presence. One afternoon, as Dora returned home and was getting out of her car, Kostas ambushed her and shot her twice with a hunting rifle. He then returned to the apartment they had rented together and shot himself. The night before her death, Dora had half-jokingly said to one of her best friends, “Can you imagine if I make the headlines like the other women?” referring to Greece’s other femicide victims.

Garyfalia’s early life in Corinth had been just as idyllic. She took ballet classes, played dress up, spent summer holidays playing with her siblings. Since her return to Velo in 2020, Garyfalia had been dating Dimitris Vergos, a computer scientist. He, too, manifested a controlling attitude. The Christmas before her death, Garyfalia had told her mother that she thought her boyfriend had hacked her phone. He was always checking where she was and what she was doing. This, in turn, had made Garyfalia irritable. In 2021, the couple decided to spend the summer camping on the Cycladic island of Folegandros. According to Vergos’ defense lawyer, on the fatal day, the couple started arguing about directions and Vergos drove the car off the road, ending up close to a cliff edge. Garyfalia’s body was found by local fishers a few hours later, floating in the sea. The forensic report showed that she had been battered and dragged unconscious across a rocky area and then pushed into the sea, where she drowned.

Until recently, femicides in Greece were officially recorded as “honor killings.” The national media referred to these as “crimes of passion.” It was only in 2020 that the Greek police modified their system to be able to register crimes of domestic violence. Now, police data includes information about the gender of the victims and perpetrators as well as the relationship between them.

Dora’s murder shook the tightknit community of Rhodes. Her funeral was covered extensively in the local press, with many asking why her killer had been allowed to keep a gun, since it emerged that he had used it previously to threaten a former partner. This was not the first time the island community had had to deal with such a crime. In November 2018, the 21-year-old university student Eleni Topaloudi had been raped, beaten and killed by two men after she resisted their advances. The killing had happened at the peak of the #MeToo movement and sparked a national outcry and discussion about femicide and gender-based violence. Feminist organizations and human rights groups organized numerous peaceful protests in the Greek capital that raised awareness about the problem and highlighted other victims of gender-based violence.

Eleni’s killers were tried in May 2020, and the prosecutor’s speech was seen by many as a milestone in the campaign to tackle crimes against women. It held up a mirror to some of the machismo engrained in Greek society. Addressing Eleni’s father, she described the two defendants as representing “the curse of life,” while his daughter “like a bright star, will always show us the way from where she is.” The killers, then aged 19 and 21, were sentenced to life in prison for murder and an additional 15 years for gang rape.

“What we want is the legal recognition in the penal code of the term ‘femicide,’” says Maria Mourtzaki, policy manager for Action Aid, “so we can give more exposure to the motives and the gender dynamics of crime against women.” This is necessary for a society that is “deeply patriarchal and conservative,” says Mourtzaki, who has been researching the impact of the Greek financial crisis on survivors of domestic abuse. The support network for survivors was built during the Greek financial crisis, she notes, but despite the increased capacity of shelters, “human resources and other support, like heath care or social work, have been reduced due to budget cuts.”

The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting lockdowns exposed the intensity and scale of the domestic violence problem. According to police records, 4,264 women were victims of domestic violence in 2020 alone. “During the lockdown a lot of women were in immediate danger due to domestic violence and had to be evacuated from their houses,” says Maria Syreggela, the former deputy minister for labor and social affairs, who is responsible for gender equality. “We got the necessary permits and despite the movement restrictions, we either helped them move in with friends or family or to our emergency shelters.” The capacity of emergency shelters for abused women increased in that period, says Syggerela.

Despite these claims, women remain unconvinced by the progress. In November 2020, during lockdown, nine women were arrested by police after staging a protest on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. Among other things, the women were protesting the length of time the Greek police had taken to arrest Babis Anagnostopoulos, 33, who was accused of murdering his wife Caroline Crouch, 20, in front of their baby daughter in May that year. After the 16th woman was killed that year, women gathered in Athens again in December to protest the femicides, with signs reading, “Women-killers have the keys to our house” and “patriarchy kills.” Criticism was also leveled at the Greek media; one response to the recent murder of a woman by her partner had involved a discussion a panel of six white men.

For centuries, femicides found a troubling acceptance in Greek society. Only in the mid-20th century did these acts begin to be seen as criminal, losing their protection under customary law. In the past, preserving family honor was seen as more important than preserving life itself, a sentiment often echoed in Greek folk songs. “Menousis,” a song sung and danced to in Greece up to the present day, which has passed into music education in schools, tells the story of a drunk man during Ottoman rule who slaughtered his wife after suspecting that she spoke to another man.

Though legal stances have gradually tightened, the grip of deep-rooted social attitudes remains stubborn. Even today, gender-based violence is sometimes excused in the name of family reputation or a man’s standing. Traditional media has played a significant role in upholding this narrative.

George Pleios, an Athens University professor specializing in sociology of mass media and culture, notes a common media response when femicides make headlines. Scrutiny often falls on the woman — her behavior, culture and appearance — thus perpetuating harmful gender stereotypes and deflecting blame from the male culprit. People have instead turned to social media to demand new measures for ending gender-based violence, including stricter punishment for perpetrators. They describe these crimes as femicide. But people on the conservative side of the political spectrum dispute that such a crime even exists. Pleios notes this aligns with their view of women’s role in society, which they see as child-rearing and housekeeping. “This conservatism is very present in the Greek media.”

Aleka visits the cemetery every day to speak to her daughter. Her sister joins her to keep her company and give her strength. She brings cleaning materials, washes the lanterns and lights the candles inside. The cemetery is surrounded by olive groves and orchards of lemon and orange trees. Aleka points to the carnations that adorn her daughter’s final resting place and says that Garyfalia is the Greek name for this flower.

“I will never accept what happened to my daughter. I will die with this pain. But I felt that if I give up on life, I would lose my other children too. So we had to stand up together,” says Aleka.

“Garyfalia lived a very happy life and this gives me comfort,” she says. “We had 25 amazing years with her. What happened is very brutal for the whole family. She was murdered and we were murdered along with her.”

Dora is buried next to her beloved maternal grandfather, whom she followed around when she was learning to walk. Dora’s family at least have the comfort of knowing their daughter’s killer is dead. “I don’t know what we would have done if he was still alive,” her aunt Cleopatra Kotti says. “Other murderers are still alive and one day they will be released from jail and will have new relationships and someone else’s daughter will not come back,” she says, citing Garyfalia’s case as an example. “The law in Greece for femicides needs to change,” she says. The life sentence was 16 years but, since Garyfalia’s murder, it has gone up to 18 years. She doesn’t think it is enough.

“Our daughters who are murdered will not have a second chance in life,” she says, “but the murderers will.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.