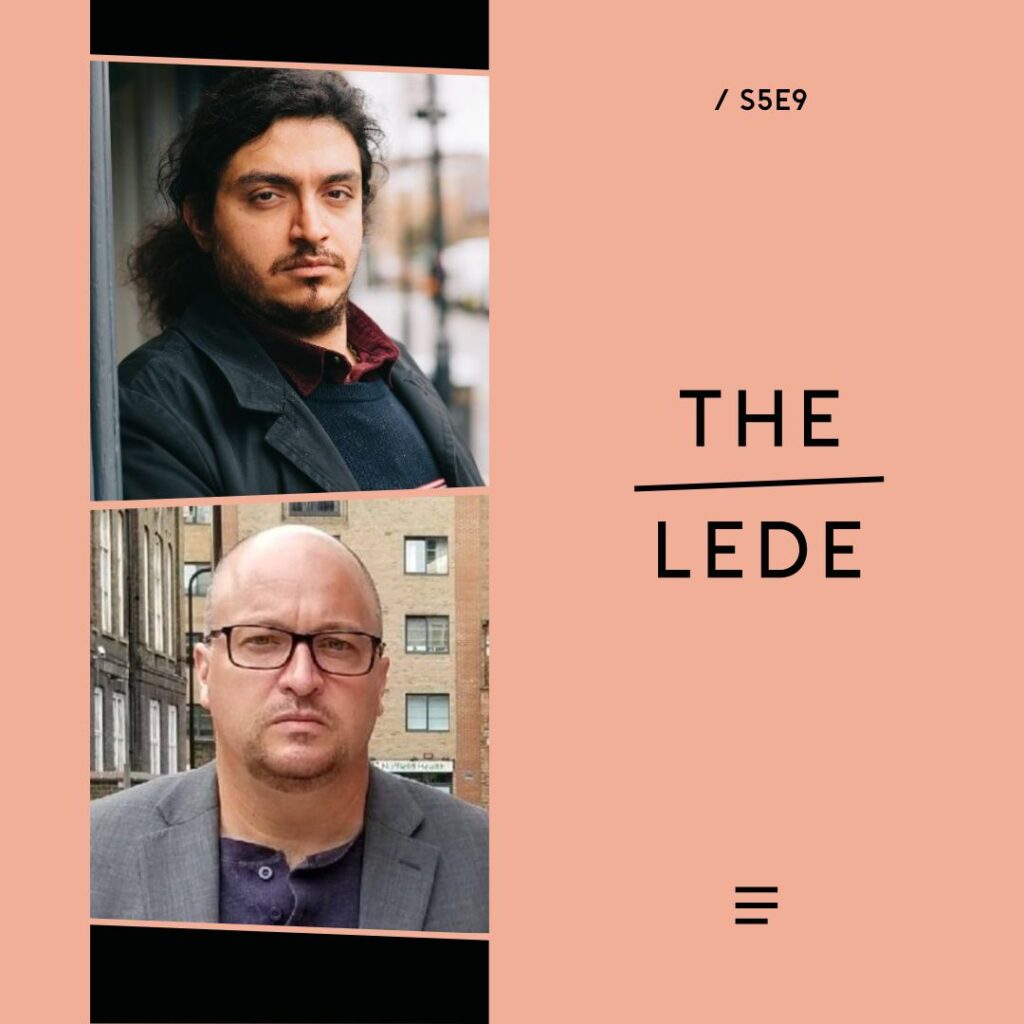

Hosted by Danny Postel

Featuring Arash Azizi

Produced by Finbar Anderson

Listen to and follow The Lede

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Podbean

In September 2022, after the death of 22-year-old Iranian woman Mahsa Amini in police custody, a movement began in Iran that came to be known by the moniker, “Woman, Life, Freedom.” Media outlets in the West highlighted one of the movement’s core themes, which was a challenge to the Islamic Republic of Iran’s mandatory hijab policy. But to Arash Azizi, that focus missed much about what made the movement so dynamic, prompting him to write his most recent book, “What Iranians Want: Women, Life, Freedom.”

“I was frustrated by a portrayal of the movement that was very flat, as if it had no history,” he tells New Lines’ Danny Postel on The Lede. “Mandatory veiling was an important part of the movement, but it wasn’t all about that. This was a multifaceted movement that had roots in decades of civil society struggles in Iran.”

“The movement really opened up questions of political change and the political future of the Islamic Republic in an unprecedented way. … It certainly made a mark on Iranian political history, and it will definitely color all future attempts for change.”

Azizi argues that the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement differed from previous protest movements inside Iran because it played out on a scale not seen in the country up to that point. “It really brought together a variety of Iranians across ethnic boundaries, across class boundaries,” he says. “It was a movement from the very beginning supported by trade unionists, the middle class and ethnic minorities all over the country.”

The movement, Azizi acknowledges, no longer exists on the streets of Iran, having been effectively shut down by the Islamic Republic through a campaign of forceful repression. Nevertheless, he argues, it had a huge impact on the history of the country.

“The movement wasn’t able to change the government,” he says, “but I think the movement really opened up questions of political change and the political future of the Islamic Republic in an unprecedented way. … It certainly made a mark on Iranian political history, and it will definitely color all future attempts for change.”

Azizi and Postel dissect the reasons for the failure of the protest movement, Azizi noting the strength of conviction of the Islamic Republic’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. “The regime is not going to collapse on its own,” he says. “The only way would be for the opposition to be able to come together, unite across the very real differences that it has, and present a coherent, organized alternative to the regime. … But the Iranian opposition didn’t do anything right. It failed to come together to present an alternative.”

Postel queries the launch and almost immediate failure of the opposition group “Alliance for Freedom and Democracy in Iran” (AFDI), which collapsed in a matter of months. Azizi notes the willingness of leading members like Reza Pahlavi to pay lip service to building an inclusive movement while undermining the movement elsewhere. “Pahlavi — they say personnel is policy. The people that surround him, his chief of staff, all the figures close to him espouse not the sort of inclusive politics that he claimed he would stand for, but far-right exclusionary politics.”

Postel raises the significance of the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel by Hamas and Israel’s subsequent war on Gaza in reinvigorating the Islamic Republic’s regional standing among its allies in the “Axis of Resistance.” “There’s one thing that the axis really does have going for it, and that’s the truth. These are the only forces that fight Israel, that are ready to fire bullets against Israeli fighters, not just with words, but with weapons,” suggests Azizi.

However, he argues that this reputation has been undermined by the Oct. 7 attacks and the subsequent fallout. “The Islamic Republic since Oct. 7 has had one preoccupation in the region, and that’s not fighting Israel. The biggest worry and concern that the Islamic Republic has is that it gets into a direct confrontation with Israel and the United States. It wants to avoid that at all costs.”