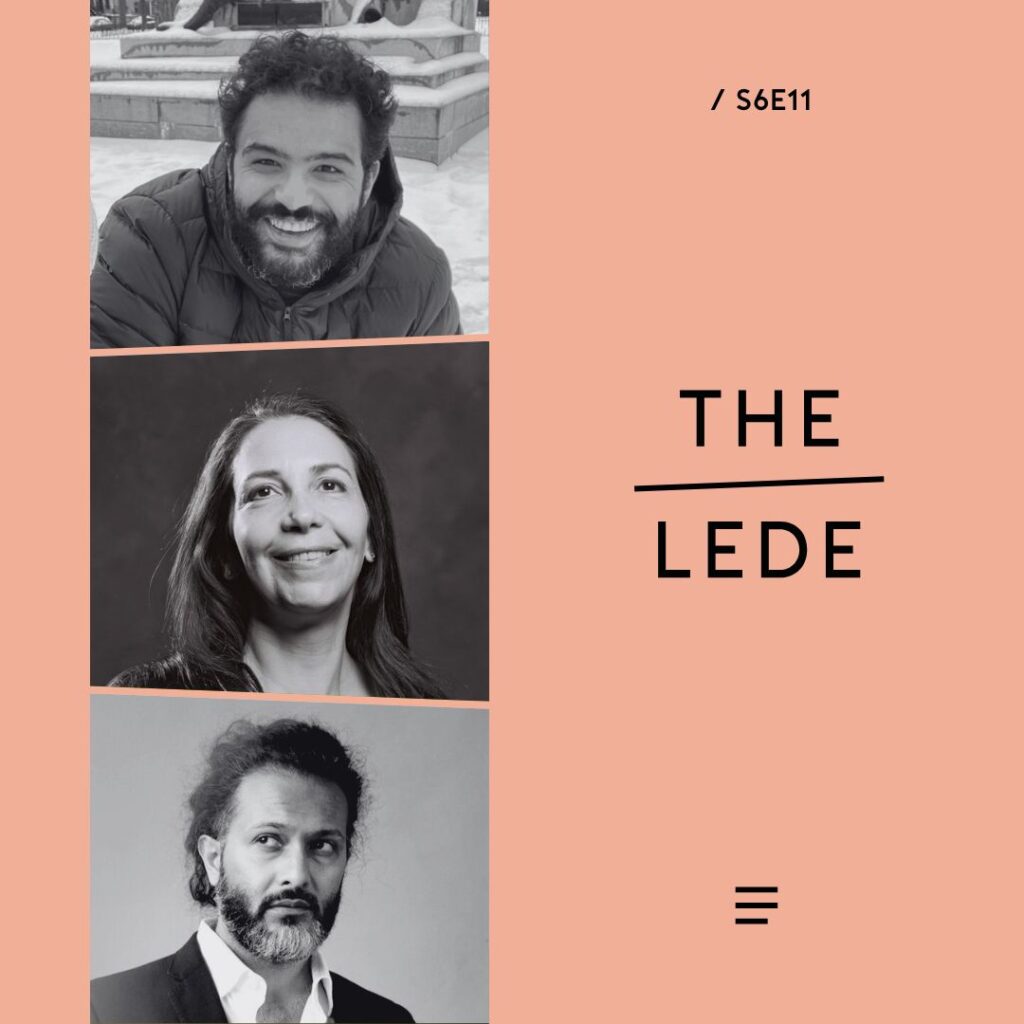

Hosted by Faisal Al Yafai

Featuring Kareem Shaheen and Rasha Elass

Produced by Finbar Anderson

Listen to and follow The Lede

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Podbean

The idea that the Assad regime’s rule over Syria was a hollowed-out house of cards was fairly widespread, New Lines’ Middle East Editor Kareem Shaheen tells The Lede host Faisal Al Yafai. Nevertheless, says Shaheen, “nobody could have imagined that this regime would disappear, even if people had a sense that the regime was weak.”

Considering the regional context is vital to understanding how the Assad regime collapsed when it did, Shaheen notes. “ People did not quite grasp how degraded the capabilities of the regime’s allies really were,” he says. “The regime has essentially survived all this time due to Russian backing and due to Iranian backing. Hezbollah and Iranian militias and Iraqi militias were crucial to their victories in cities like Aleppo, as well as being backed by Russian air cover. None of this could have happened without all of the regime’s allies banding together in order to reclaim all of this territory. And the past year has shown us how weak that backing has become.”

“Nobody could have imagined that this regime would disappear, even if people had a sense that the regime was weak.”

One of the key images that symbolized the end of the Assads’ hold over Syria was the release of prisoners from the Sednaya prison complex, which had become a veritable black hole for the nation’s disappeared. “Everybody in Syria knows someone, a loved one, who had disappeared. And this is not just from the civil war, not just since 2011, but really for the duration of the 50 years of the Assad regime,” notes Rasha Elass, the magazine’s editorial director. “The trauma that is unfolding from this — we haven’t even begun to grasp the extent of it for the prisoners, for their loved ones and for the Syrian people,” she adds.

Despite the outward joy from so much of Syrian society, there have been muted reactions to the fall of Assad in the region, notes Shaheen. “People are almost afraid to be hopeful,” he says. “We’ve been so accustomed to tragedy over the past 13 years in the region, since 2011 and way before.”

Shaheen notes that much of the skepticism has come from those who define themselves as anti-imperialist, a position he feels is inconsistent. “What is the concept of resistance supposed to be about? It’s supposed to be about dignity and about people’s right to self-determination. And how can you deny that from Syrians who’ve suffered under one of the most brutal police states of the past 50 years?”

That’s not to say that Syria’s future is secure, cautions Elass. “Syria right now is going to need a lot of friends, it’s going to need a lot of cash, it’s going to need a lot of goodwill,” she says. “It can’t afford the slightest marginalization, continued sanctions or any such thing, because that will be a disaster and a recipe for failure. It needs the support of the international community and certainly of its neighbors.”

Further reading:

The Backstory Behind the Fall of Aleppo by Hassan Hassan and Michael Weiss

Assad Was Disengaging From Iran, but His Next Steps Are Unclear by Rasha Elass

Syrians Ponder a Future After Aleppo by Kamal Shahin

Dawn in Damascus by Kareem Shaheen

Liberation in Syria Is a Victory Worth Embracing by Layla Maghribi

With Assad in Moscow, Putin Scrambles To Save Face — and his Syrian Bases by Amie Ferris-Rotman

Hope and Despair at Assad’s ‘Human Slaughterhouse’ by Aubin Eymard and Cian Ward